Woodwinds | The Saxophone Family

Woodwinds | The Saxophone Family

Extreme Orchestration

by Don Freund and David CutlerPublished: February 2024

THE SAXOPHONE FAMILY.

The saxophone and clarinet families have many things in common. They are the only single reed families. Both have a relatively large number of instruments covering virtually the complete range of the orchestra, and these instruments are playable at the elementary level, while possessing the capacity for virtuosic technical agility and extraordinary dynamic breadth. While clarinets have cylindrical bores, saxophones are conical (as are oboes and bassoons), and saxophones overblow at the octave, not the 12th. Saxophone fingering matches clarinet fingering in the clarinet's clarion register. This fingering and reed-type similarity contributes to the ties of the saxophone to the clarinet as a "double," but the saxophone has fully emerged as an independent family of instruments.

Although all saxophones are made of brass, their method of tone production and sound wave control place them in the woodwind choir. The saxophone family is unique in that the entire family appeared at the same time, the invention of one man (Adolphe Sax, around 1840), completely circumventing the slow evolutionary development practically every other instrument has undergone. As a result, there is a consistency throughout the family not found elsewhere. Sax was conspicuously successful in creating woodwind instruments that are naturally loud, capable of competing dynamically with brass (although eventually losing the competition at the extreme fff end). It takes some artistry to play the saxophone with the control needed at softer levels to balance its woodwind cousins. Fortunately, this level of artistry is no longer rare; saxophone performance study at practically all music schools and conservatories stands on equal footing with other orchestral winds.

The identification of the saxophone with jazz and popular music gives it an intriguing, but sometimes inappropriate, reputation. It is certainly a blessing that saxophonists are more likely than other classical musicians to be adept at injecting pop and jazz flavors in "concert" scores as needed. However, it is often necessary for composers to avoid potential type-casting by studying the many ways saxophones have been used in "art music" contexts.

Please note: Saxophonists generally use different types of mouthpieces and reeds to get a “jazz” sound as opposed to a “classical” sound. Composers who believe their players can immediately and convincing switch from Ravel to John Coltrane should keep in mind the role equipment plays in establishing timbral character.

All the surviving members of the saxophone family have the same fingering and basic written range, and have similar register qualities; the various-sized instruments of the family transpose the written pitch to some octave of Eb of Bb. (Ravel’s F Sopranino in Bolero is long extinct.) The most common saxophones form a four-voice quartet: Bb Soprano, Eb Alto, Bb Tenor, Eb Baritone. The Bb Bass would be a wonderful resource but is relatively rare. Less common still are the Eb Sopranino and the Eb Contrabass.

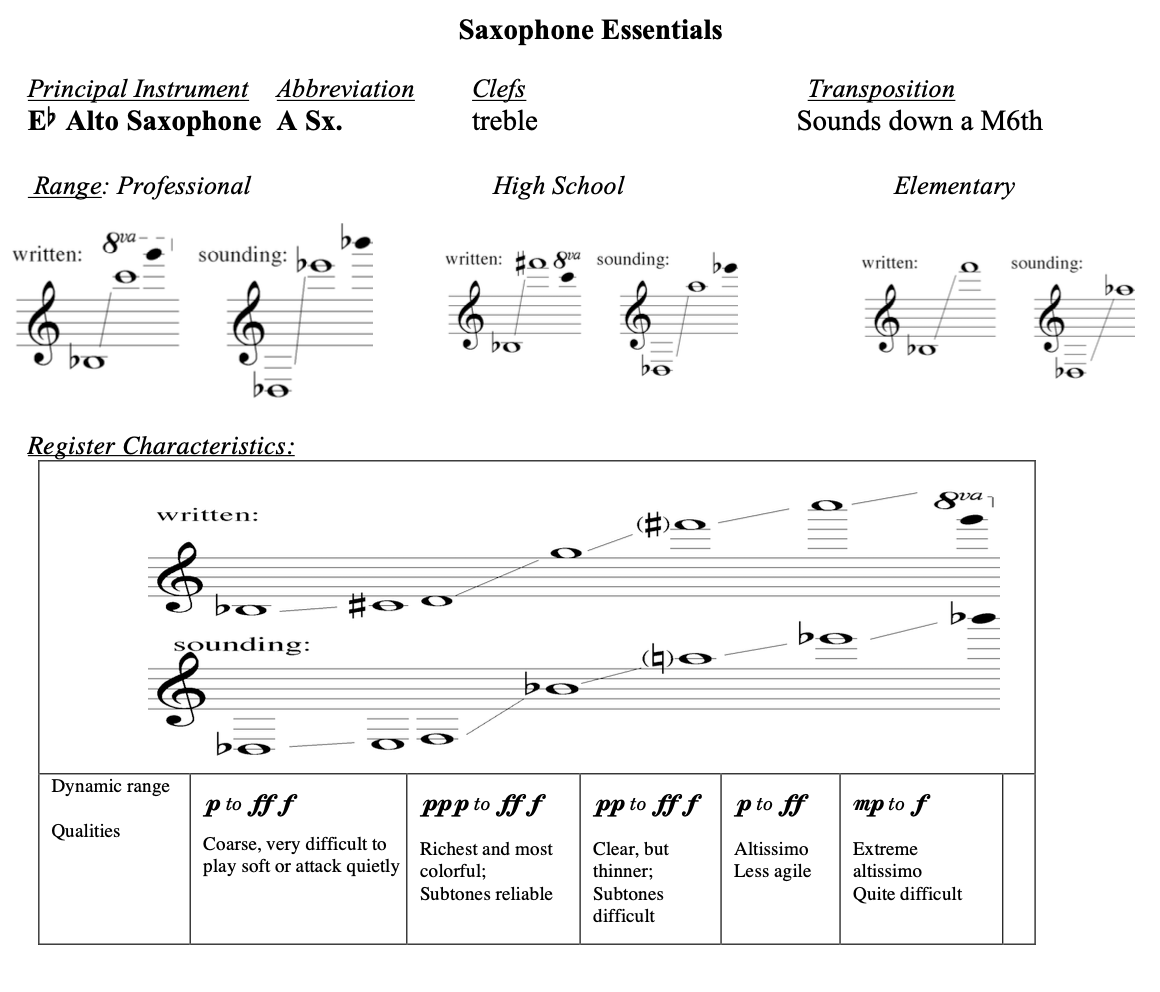

THE EB ALTO SAXOPHONE: A GUIDE TO THE REGISTERS.

Since all members of the saxophone family were, by design, created equal, singling out the E♭ Alto as the "principal instrument" is less appropriate than the choice of the stars of the flute, oboe, clarinet, and bassoon families. The word "saxophone" doesn't automatically default to the Alto Saxophone. We've chosen the Alto as our paradigm because it is the most commonly used saxophone in concert music solos and chamber music, and the one most commonly found in orchestras. Its register characteristics also provide a fairly reliable model for the family as a whole.

The bottom four notes of the saxophone are progressively more difficult to play softly as one descends. Quiet attacks are particularly treacherous in this region. Above this danger zone, the lowest octave and a half has the instrument's richest colors and its most full-bodied fff 's. Saxophonists can play notes in this region with an extremely soft subtone. Above written G5, the saxophone becomes brighter and clearer, resembling the clarinet's clarion register. (It could be said that the lower register resembles an oboe, but with a dynamic range that oboists can only dream of.) The top of the conventional range of all saxophones is written F♯6, but players spend a great deal of their practice time developing their technique in the area above this pitch, called altissimo, extending the range of the instrument upward. It may seem that "the sky's the limit" here, but as might be expected, pitch, facility, and tone color become more unpredictable the higher one gets. Composers can write for solo playing in the area from G6 to C7 (written pitches) with some confidence, with only a moderate lowering of technical demands. Above this region, results are variable, with the choice of reed and how it may be functioning on any particular day a major factor.

SAXOPHONE STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS.

Not only does the design of the saxophone create fewer inherent technical problems for the performer than other woodwinds, but the popularity of the instrument has produced an army of dedicated, underused musicians eager to push the envelope of the instrument's capabilities. Demands once thought impossible, such as very low soft tones and double and triple-tonguing, may now be executed by many professionals with apparent effortlessness. Velocity and agility of tonguing are equivalent to the clarinet. All trills and tremolos are effective up to the altissimo range.

The smoothness and consistency of color throughout the saxophone's pitch and dynamic range can be a curse as well as a blessing. Left to its default sound, a saxophone can be monochromatic. The relatively wider bore of the saxophone gives it strong lower partials, but this creates less emphasis on higher partials that contribute to color. Due to this limitation, it's up to the player to provide the color that is intrinsic to other woodwinds. Details of articulation and dynamic nuance and even a greater than usual amount of descriptive words are especially appropriate in saxophone writing. The instrument is particularly well equipped to respond effectively to these, and saxophonists are often uncommonly earnest about making the most of what the composer gives them.

In orchestras, wind ensembles, and bands, saxophones create a wonderful bridge between the brass and woodwind sections. They blend exceptionally well with brass, filling in and rounding out the sound of that section.

THE BB SOPRANO SAXOPHONE.

It has been suggested (but never explained: perhaps a coincidence) that members of the saxophone family in B♭ (the soprano, tenor, and bass) are naturally somewhat "coarser" than their E♭ siblings (alto and baritone). The soprano saxophone is edgier and reedier than the alto when playing in the same concert range, approximating the timbral and articulation qualities of the oboe. This is not surprising, since its "oboe-like" low register sounds a perfect 5th higher than the alto, making the range from sounding C4 to F5 especially pungent. The altissimo register is generally undeveloped on the soprano, perhaps because it is rarely requested; a curious result of this is that many players do not play as high a sounding range on the soprano as they can on the alto.

The Bb Tenor Saxophone.

Moving the register characteristics of the alto down a perfect 4th creates a strikingly different personality in the tenor saxophone, more intense towards the bottom, more lyrically insistent and pleading towards the top. In solo passages it can sound more like a cello than any other woodwind instrument. The tenor’s facility rivals the alto, and although its virtuoso prowess is less frequently heard in concert music, jazz tenor and alto players are known for equivalent agility. The altissimo of the tenor saxophone conforms to the same written range characteristics one finds in the alto.

The Eb Baritone Saxophone.

The character of the baritone saxophone contrasts strongly with the tenor. The baritone has a smoother, more comfortable tone quality — a more open-throated richness. (It’s amazing how much these characterizations of the saxophone quartet resemble characterizations of the corresponding operatic voice types!) Baritone specialists have less trouble controlling volume and attacks in bottom range, and have developed their altissimo to give the instrument the largest range of the family. It is the saxophone capable of producing the clearest articulation and cleanest staccato.

SAXOPHONE DOUBLING.

Practically all advanced saxophonists work to maintain a high level of artistry playing several members of the family; doubling is more common within the saxophone family than it is within any other woodwind family. In the symphony orchestra, it is rare to score for more than one saxophone, presumably for economic reasons. This is usually an alto, but there is little practical reason why this single player isn’t put to a more extensive use of doubling. Doubling on soprano from all instruments is common. Moving from alto to tenor is more difficult. Baritone players are usually specialists, although most baritone players can also play alto and soprano. The standard section of saxophones in wind ensembles is 2 altos, 1 tenor and 1 baritone, though occasionally a soprano is added or substituted for one of the altos.

Saxophone Family Orchestral Examples.

Here are examples from orchestral literature that demonstrate characteristics of the saxophone family.

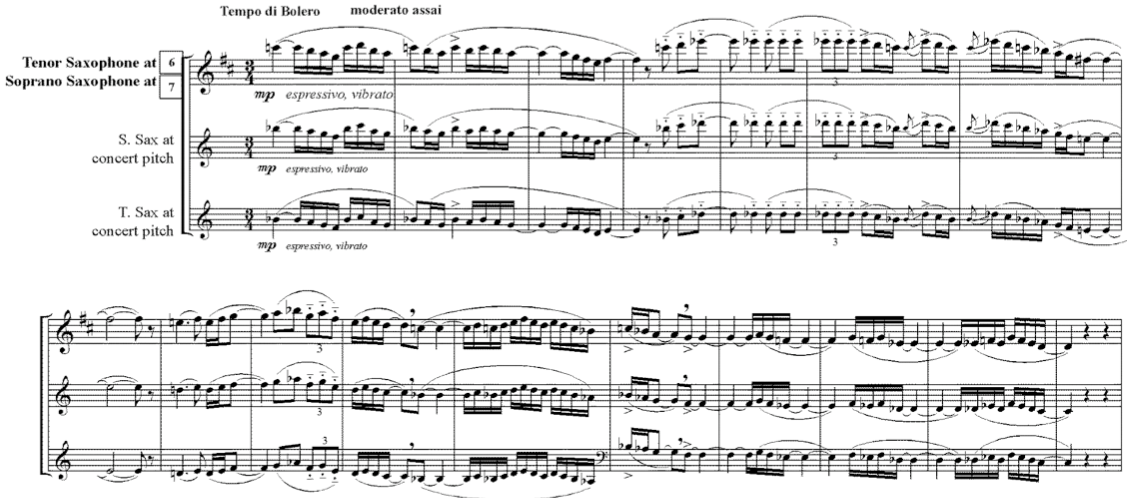

SOPRANO AND TENOR SAXOPHONE EXCERPTS.

Ravel: Boléro, rehearsal number 6 and 7. This excerpt displays not only the singing tone of the saxophone, but also the consistency of quality found throughout the family. This passage is played by the tenor saxophone at rehearsal number 6, and then by the soprano at 7. The score indicates F sopranino at 7, but this is always played on the soprano. Although only one dynamic level is indicated, this excerpt shows a great range color due to its use of much of the saxophone's range, and an effective mixture of articulations, grace notes and long slurs.

Instrument Studies for Eyes and Ears (ISFEE) | Soprano and Tenor Saxophone

Soprano Saxophone

Tenor Saxophone

Mussorgsky/Ravel: Pictures at an Exhibition, The Old Castle, rehearsal number 20-23, 32-end. This most famous of all orchestral saxophone solos is modest in terms of range, covering only the middle octave and a fourth of the instrument’s range, and limited in dynamic contrast until its last statement. Its memorable quality comes from the alto saxophone’s ability to project the line simply and with penetrating power, even at a relatively quiet dynamic level. The version in C shows the phrase markings as Mussorgsky put them in the piano score; observe the way Ravel added dynamic indications and changed phrase markings to create wind slurs. Note also that Ravel doesn’t always follow our slurring “do’s and don’t’s,” placing repeated notes under basic slurs.

Strauss: Symphonia Domestica, rehearsal number 136, 158. This example is not a solo; it shows the baritone saxophone used as a strong doubling voice, adding both dynamic power and clarity to an athletic bass line. This work was originally scored to include a quartet of saxophones in C and F; it is now played with a section of Bb soprano, Eb alto, and two Eb baritone saxophones.