Bowed Strings | Left Hand Techniques

Bowed Strings | Left Hand Techniques

Extreme Orchestration

by Don Freund and David CutlerPublished: February 2024

On string instruments, it is possible to change the pitch of a string by stopping the string with the left hand. In other words, the left hand applies pressure to a string against the fingerboard, in essence shortening its length. Shorter strings produce higher pitches, so as notes are stopped higher on the fingerboard, the pitch rises.

Pitches can be stopped with any of the four fingers on the left hand (not including the thumb), which are identified as the first through fourth fingers. The notes that can be reached without moving the location of the hand on the fingerboard constitute a position. As the music changes registers, shifts to higher or lower positions are necessary. On violin, in first position (the lowest position), a span of about a fourth is possible from first to fourth finger. While this may seem like a small range, keep in mind that between the four strings, first position alone spans over two octaves. Pitches get closer together as the hand moves higher on the fingerboard, so even larger intervals may be reached. The diagram below shows the notes that are possible in the first five positions of the violin. Accidentals added to these pitches are possible as well.

Figure 1: Fingerings for the violin

As can be expected, the notes on cello and bass are further apart than on violin and viola. In order to compensate for this, thumb position may be used on these instruments, allowing the use of all five fingers on the left hand. By stopping a string with the thumb, wider intervals can be reached.

Although shifting is certainly a common practice, playing a passage in one position is easier than one that requires frequent shifts. As an orchestrator, it is helpful to minimize the number of shifts that are necessary, and consecutive shifts are easiest when they move in the same direction. One of the biggest pitfalls of bad string writing is a lack of consideration given to position shifts. String players are certainly used to shifting, but once they are placed in a position, let them play something there before moving on! It is irritating to have to switch positions to catch single pitches. This is especially important to bear in mind for rapid passages.

The longer the string, the larger the physical space between a given interval. For this reason, notes are further apart on the cello and bass than they are on violin or viola, and the lower instruments are restricted to a narrower range in comparable positions.

While playing in tune is an issue for many instruments, it is a particular challenge for string players. Since these instruments have no frets, buttons, or valves, the only way to learn where a note is positioned on the fingerboard is through repetitive practice. Intonation is a constant preoccupation for even the best string players. Pitches in higher positions are generally more difficult to play in tune than those in lower positions, and higher positions have less flexibility, making rapid passages more difficult.

Open strings project more than stopped strings, and help facilitate easier multiple stops (see below). They are a favorite with fiddlers, yet orchestral players tend to avoid open strings in exposed passages. Because their timbre is substantially different, and vibrato cannot be applied to these notes, they tend to stick out in melodic passages. Instead, the same pitch on the next lower string will be stopped. The obvious exception to this is the open IV string, the lowest tone attainable on the instrument. To guarantee that an open string is played, the number ‘0’ should be written above the pitch.

Figure 2: Alban Berg Violin Concerto (1935) mov. II, mm. 60–90

Most passages allow a choice of strings for execution. Playing on a lower string in a higher position will result in a darker and more intense sound than the higher string, lower position alternative. To indicate that music should be played on a particular string, write the Roman numeral (ex. IV), or the word sul, followed by the string name (ex. sul G). If no indication is made, the choice of strings is left to the performer. This marking is most common with the two lowest strings. The violin passage below, played in first position on the D string, would result in a fairly dull sound. Performing it on the G string places it in fifth position, making it more powerful and romantic.

Figure 3: Concerto for Orchestra, Sz.116 (Bartók, Béla), mm. 93–98

It is possible to have string musicians play multiple stops—two, three, or even four notes at the same time. (In this case, the word stop refers to the number of strings played, not stopping the string with a finger.) All of the notes in a given multiple stop must be playable on adjacent strings in the same position. In addition to facilitating extra sounding pitches, they are effective ways to add thickness or intensity to a passage. However, multiple stops can sacrifice the clear tone and refined vibrato that is possible with single pitches, and can be harder to play.

A double stop occurs when two notes are played simultaneously. When writing double stops, keep the following rules in mind:

The two pitches of the double stop must be played on adjacent strings.

Double stops that include one or two open strings are easy to play.

If one of the pitches is an open string, almost any interval between the two notes is possible, provided that the non-open string pitch is available on an adjacent string.

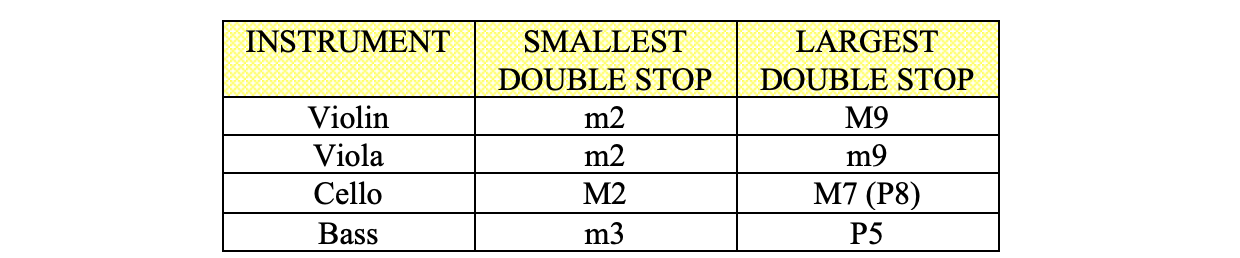

The chart below lists the smallest and largest possible intervals for double stops in low positions that do not include open strings. Slightly larger intervals may be reached in higher positions.

As double stops are played in higher positions, it is possible to reach slightly larger intervals. However, higher double stops are more difficult to play in tune.

The most difficult double stop to play in tune on violin, viola, and cello is the perfect fifth, since it requires both pitches to be stopped with the same finger; intonation becomes increasingly more difficult as the fifth moves up the fingerboard. A similar problem occurs with perfect fourths on bass.

For the most part, unisons are only practical when one of the strings is open.

Passages that contain multiple double stops can be difficult, especially if the interval between the pitches changes, and if there are no, or few, open strings. Of course, this is more practical at slower tempos.

Passages that use parallel intervals (such as a succession of 6ths) are more feasible.

Though double stops without an open string are possible on bass, they are usually only effective if one of the notes is played on an open string.

Three note chords, called triple stops, and four note chords, called quadruple stops, are also possible on string instruments. These types of multiple stops may be played a) with all pitches sounding simultaneously, or b) as a broken chord. For all the pitches to sound at the same time, the less common method, the dynamic must be forte or higher, and the pitches can only be held for no more than approximately a half a second. Double basses cannot play triple stops in this manner, and quadruple stops are possible only on violin and viola. More often, the broken chord method is used. Example ___ shows some written triple and quadruple stops and some possible they might be performed.

When writing triple or quadruple stops for violin, viola, or cello, keep the following guidelines in mind.

The more open strings, the more feasible the multiple stop.

The easiest triple and quadruple stops to play, without any open strings, combine fifths and sixths.

A perfect fifth or sixth combined with a smaller interval or an octave is possible on violin or viola, but is difficult to play.

Stacked perfect fifths are not feasible, since it requires a single finger to stop more than two strings.

Triple-stops where all strings are stopped, the outer interval spans at least a sixth and no inner interval exceeds a tritone, are also conceivable, but difficult.

How well will my multiple stops be performed?

If you write double stops that include an open string, they will probably be sight-read accurately by an experienced player. The same is true for triple stops with two open strings.

If more than one pitch must be stopped, the results may vary. When sight-reading, many string players only play the top note of multiple stops, even if the chord is quite feasible. This does not mean that multiple stops should not be written. It simply shows that they are more difficult to get in tune than single pitches, and players often err on the side of caution when sight-reading. With practice, a well written multiple stop passage can be played in tune. If you have limited rehearsal time, avoid non-open-string multiple stops when possible.

Inside info: Most orchestras will convert multiple stops into divisi with or without the conductor’s knowledge, even in works by Beethoven and Brahms where the composer clearly wanted the sound of the multiple stop. Unless a special effect is desired, dividing the strings is usually a better alternative than writing multiple stops.

A common and effective string technique is to arpeggiate a three or four note chord. Any fingering that works for a multiple stop can also be used for arpeggiations.