Bowed Strings | Alternative Timbres

Bowed Strings | Alternative String Timbres

Extreme Orchestration

by Don Freund and David CutlerPublished: February 2024

ALTERNATIVE STRINGS TIMBRES.

It is possible to achieve a greater variety of timbres with the bowed strings than with any other orchestral instrument. Through the use of harmonics, mutes, varied bow placement, plucking or striking the strings, and other extended techniques, a large selection of sound possibilities becomes available. When an alternate timbre is desired, a word indicating the new technique, a special notation, or both, must be employed. Usually a word or notation is also required to cancel out the technique.

PLUCKING THE STRINGS.

Preferred Indication: pizz. (It.) | Cancelled by: arco

Possible on: All strings

Plucking the strings is a common technique that provides a drastic contrast to arco. Pizzicato normally involves plucking the string with the flesh of fingers on the right hand. It takes a small amount of time to switch from arco to pizz. and back. Before making this switch, try to leave at least a second of rest. When switching immediately from arco to pizzicato, end the arco passage with an up-bow, so that the fingers are close to the strings and ready to begin plucking. Similarly, closely following a pizzicato passage, a down-bow should begin the bowed material.

When writing pizzicato figures, keep the following in mind:

-

Larger instruments have more sustaining power than smaller ones. A plucked bass or cello note will sustain for a much longer time than one on violin.

-

If you want a pizzicato note to be sustained, write an open ended tie or the term ‘l.v.’ (let vibrate) on the score.

-

Pizzicato notes at a given dynamic level often sound softer than arco notes at the same dynamic. In ensemble writing, consider marking these passages one dynamic level higher in order to balance with other instruments.

-

While some players can play pizzicato faster and more consistently than others, as a rule of thumb, don’t write pizzicato sixteenth notes faster than q=84. For extended passages of straight 16th notes, even this tempo is very difficult.

-

Pizzicato can be fatiguing. Leave rests regularly if possible. Even a single rest in an active plucked line can be helpful. (When Stravinsky revised Petrushka, he weeded out the pizzicatos, leaving only the main notes plucked while winds played entire lines.)

-

Keep in mind that the higher the left hand position, the duller the plucked note will be. The most resonant pizzes are open strings, natural harmonics, and stopped notes in the lower positions. This is especially true for slurs and glisses.

In addition to plucking single notes, it is possible to pizzicato multiple stops. Any of the configurations described in the multiple stop section can be plucked as well. Ordinarily, players will roll chords of three or four notes from the bottom up. Write ‘non-arp.’ to avoid rolling the pitches, or use the ‘]’ symbol. It is also possible to pluck two pitches on non-adjacent strings.

Several other plucking methods are possible. In addition to the ‘pizz.’ indication, terms or notational symbols, placed above the staff, are used to indicate these techniques. Don’t forget to write the word arco when returning to the bow. The chart below describes several other pizzicato methods.

HARMONICS.

As stated in chapter 2, the overtone series plays an important role for all pitched instrumental families. For strings, all of the techniques discussed up to this point entail playing fundamentals, or first partials. However, with harmonics, it is possible to sound higher partials in the overtone series. There are two reasons to play harmonics.

-

Unique Timbre. The tone is different than an ordinary stopped pitch. Harmonics have a fluty, silvery tone, devoid of upper partials.

-

Extended range. Harmonics expand the range of string instruments upward. In fact, with harmonics, it is possible to have the violin play tones higher than the top note of the piano.

-

Facilitate wide leaps. Sometimes it is desirable to have a passage mainly played in a lower position to contain one or several higher pitches. Instead of switching positions, it may be possible to add harmonics.

Harmonics are effective for upper pedal tones, isolated pitches, short melodic passages at moderate or slow tempos, and as a special effect. Extended passages of rapidly changing harmonics are difficult to execute, and should be avoided. Some harmonics take a second to speak, and are risky for pitches of short duration. There are two types of harmonics: natural and artificial. Though natural harmonics are often easier to play, artificial harmonics will be discussed first, since they are easier to conceptualize for most students.

ARTIFICIAL HARMONICS.

Artificial harmonics occur when one pitch is stopped, and another, higher pitch on the same string is lightly touched. The most common artificial harmonic, and easiest to play, is called a touch-4. This means that one note is stopped (for example, F), and the pitch a perfect fourth higher (Bb) is lightly touched with a higher finger on the same string. The resultant sound is a tone two octaves higher than the stopped pitch, the fourth partial in the overtone series. Artificial harmonics are notated with a normal notehead for the stopped pitch, and a diamond notehead for the lightly touched pitch. In some scores, the sounding pitch is also written with a stemless notehead in parenthesis, but this information is redundant and not necessary.

A vast majority of passages played with artificial harmonics use the touch-4 method. Other intervals may be lightly touched as well, though they are harder to execute. Refer to the chart below.

Touch-4 harmonics are common on cello, and they must be played in thumb position (see p. ___). It takes a second to move into this position, so be sure to leave a few beats of rest. Though some solo literature for bass calls for artificial harmonics, it is difficult to perform these. Though touch-m3 harmonics are technically possible on bass, they should not be written in orchestral music.

NATURAL HARMONICS.

The concept behind natural harmonics is exactly the same as for artificial harmonics: there is a stopped pitch and a lightly touched one. The difference is that, with natural harmonics, the “stopped” pitch is an open string. Because of this, it is possible to touch larger intervals above the stopped pitch, allowing other partials to sound. Refer to the chart below for natural harmonics.

On violin, viola, and cello, only the first six partials are practical to play. For the double bass, because its strings are much longer, it is possible to execute higher partials. Notice that there are several places where most natural harmonics can be touched.

There is no single standard way to notate natural harmonics. Some composers simply write the desired pitch with a little circle over it. The problem with this notation is that it leaves the question of how to play the harmonic to the player. The conversion from fingering harmonics to sounding pitches is not understood by all, and this approach may result with wrong notes or pitches in the wrong octave. This notation should only be used for harmonics where the sounding and lightly touched pitches are the same, as with the case of touch-octave.

A more effective way to notate natural harmonics is to write a diamond notehead on the lightly touched pitch. If there is any possible doubt on which string it should be played, show this with a Roman numeral. Additionally, the sounding pitch can be written as a stemless notehead, in parenthesis. Below, all the possible natural harmonics on the C string of a cello are shown.

The following chart lists the all of the possible harmonics on the violin. Transposing the chart down a perfect 5th gives harmonics for the viola; down an octave and a fifth gives cello harmonics (but remember that touch-5 is impossible on cello).

Violin Harmonics

To sum up, consider the following when writing harmonics:

The safest passages consist of a succession of natural harmonics, touch-4s, or a combination of the two. When in doubt, use all touch-4s.

Avoid switching between artificial harmonics of different intervals.

Avoid substantial position shifts on the fingerboard.

Harmonics are easier to play and speak more clearly on cello and bass, due to the longer and thicker strings.

Touch-m3 artificial harmonics should only be considered on the cello.

Bass can play artificial harmonics in the high (thumb) positions, those these are not recommended in orchestral writing. However, quite high natural harmonic partials are possible.

Vibrato is usually not possible with harmonics.

MUTES.

Preferred Indication: con sord. (It.) | Cancelled by: senza sord

There are two reasons for muting string instruments:

change timbre.

play softer.

String mutes, made of wood, plastic, or metal, clamp on to the bridge. The mute functions as a low pass filter, absorbing some of the higher frequencies from the instrument, creating a thinner, smoother sound. Though the mute does dampen the output volume, and most muted passages are written at soft dynamics, loud muted playing is also quite effective, sounding intense and constricted. It is not necessary to use a mute every time the strings are asked to play at soft dynamics.

It takes time to attach or remove the mute. Though the amount of time it takes varies depending on the mute type, as a rule of thumb, leave at least four seconds of silence to enable a player to attach the mute, and two seconds to remove the mute.

Some composers of solo and chamber music have requested practice mutes, which were invented to enable players to practice at much softer dynamics. Practice mutes muffle the instrument drastically, and can only be play pp and softer. Used only for special effects, this is indicated by writing “with practice mute” in the score.

Trick of the Trade

It is expected for string players to carry mutes with them at all times. However, occasionally, you may find yourself at a rehearsal with a muteless participant. Fret not. It is possible to achieve a muted sound by taking a folded dollar bill and weaving it through the strings. Though bills are not as effective as normal mutes, in a pinch, they can come in handy. (And it only costs a buck!)

BOW OVER FINGERBOARD.

Preferred Indication: sul tasto (It.) or flautando (It.) | Cancelled by: ord.

Possible on: All strings

Ordinarily, string players bow their instruments approximately halfway between the fingerboard and the bridge. By changing this placement it is possible to alter the tone of the instrument. Bowing over the fingerboard results in a soft, fuzzy, almost flutelike tone. Sul tasto combined with non-vibrato is a particularly effective, haunting combination.

BOW NEAR BRIDGE.

Preferred Indication: sul pont. (It.) | Cancelled by: ord.

Possible on: All strings

By bowing near the bridge, an eerie, scratchy, glassy tone emerges. Although any bowed passage may theoretically be played sul ponticello, it is most effective for 1) fast, moving passages; 2) trills; 3) bowed tremolos; and 4) fingered tremolos (see page. ___). Sincer sul pont. accentuates high partials, it is absurd (though interesting) to perform this with a mute, since a mute filters out these partials.

Trick of the Trade

Though a sul pont. indication means that players should bow near the bridge, many performers are timid about applying this technique. If you desire a particularly harsh sul pont. sound, to the point where pitches may become obscured, assure the players that this is what you want by writing ‘extreme sul pont.’ or ‘bow directly over bridge.’

BOW WITH THE WOOD OF THE BOW.

Preferred Indication: col legno tratto (It.) | Cancelled by: ord.

Normally, the hair of the bow is drawn across the strings to produce a tone, but it is also possible to flip the bow over and use the wood. Bowing with the wood creates a frail, eerie tone that is possible only at soft dynamics. To slightly increase the dynamics and stability, many players turn the bow on its side so that edge of the hairs also rub against the string. Col legno tratto is most effective for tremolo, though it can also be used for legato melodies.

STRIKING WITH THE WOOD OF THE BOW.

Preferred Indication: col legno tratto (It.) | Cancelled by: ord.

Striking the strings with the wood of the bow creates a percussive attack. More common than col legno tratto, this effect is most effective for rhythmic passages.

Trick of the Trade

Many string players do not like to perform col legno passages because it can damage their bows. This is an understandable concern, as bows often cost thousands of dollars. Some performers own a second, cheaper bow, used primarily for col legno passages. If you are stuck in a situation where a player is concerned about bow damage, a similar effect is possible by striking the string with the tip of the bow. Incidentally, it is also possible to strike strings with other objects, such as pencils, drumsticks, glass rods, or chopsticks.

RETUNING OPEN STRINGS.

Scordatura, altering the tuning of one or more strings, is not a new concept. Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber wrote Baroque violin sonatas that required alternative tunings in the late 1600s. Some reasons for retuning the string are:to expand the range of the instrument lower than the normal lowest string;

to change the timbre (tuning the strings higher makes the sound brighter, tuning lower

makes it darker);

to have a different open string note, perhaps to be used as a drone;

to allow for different natural harmonics;

to facilitate new multiple stops that are not possible with standard tuning.

In order to execute certain musical ideas it can be helpful, or even necessary, to use scordatura. However, this device creates some challenges. First, notes on retuned strings need to be written as they would normally be fingered, not as they sound. Suddenly these instruments (or some of their strings) becoming transposing entities. For a player who is used to particular notes sounding a particular frequency, this can become quite confusing. Also, retuning the string to the normal pitch can be time consuming and difficult, as the tuning of other strings may be affected. Scordatura is especially rare in orchestral repertoire because of the logistics of an entire section retuning a string to an unusual pitch. If a scordatura passage is required, many string players opt to use a second instrument for those areas. At the beginning of a piece or passage that requires the retuning of strings, the alternative must be notated clearly for the performer.

Trick of the Trade—Bass Scordatura

Many bassists tune the strings of their bass up a whole step when performing solo literature. This requires special, thinner strings to be placed on the instrument (so the neck doesn’t snap!) The resultant sound is brighter, lighter and clearer than a normally tuned bass would sound. No other instrument has such a tradition.

INFLECTIONS .

It is possible to inflect string pitches in a number of ways.

VIBRATO.

String players naturally add vibrato, a regular fluctuation of the pitch, to all sustained pitches, adding expressiveness and beauty to the music. Produced by rocking the stopping finger back and forth on the fingerboard, the amount of vibrato employed varies from performer to performer. Vibrato cannot be applied to open strings, though these notes are so naturally resonant that their vibrations simulate a stopped vibrato pitch.

At times, it is effective to ask for a passage to be played straight tone, without any vibrato. Best at softer dynamics, the resultant sound is eerie and haunting, devoid of expression. ‘Non-vib.’ should be written on the score. The opposite end of the spectrum, ‘molto vib.’ or ‘extra wide vib.’ produces an excited, out-of-control warble. All of these indications are cancelled out by the phrase ‘normal vib.’

TRILLS.

Trills are common and effective on all string instruments. As stated in chapter 2, there should be no question about the pitch of the trilled note. A section of string instruments trilling a single pitch can generate a good deal of excitement. Trills of open strings should be avoided. Because the pitches of the open I, II, and III strings can all be duplicated on lower strings, the only ineffective trills occur with the open IV string.

TREMOLOS.

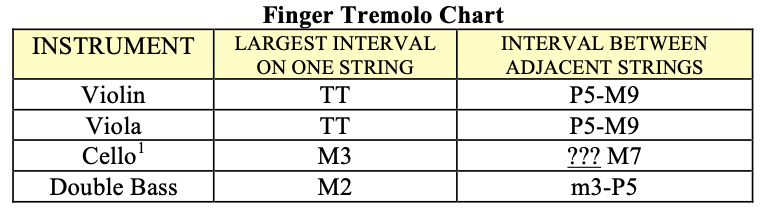

Tremolo is a term that has different meanings for different instruments. On strings, there are two types of tremolo: fingered and bowed. Fingered tremolos quickly oscillate between two pitches, resembling trills. While trills are always a half- or whole-step apart, fingered tremolos may alternate between larger intervals. Though tremolos rocking between two adjacent strings are possible, they are most effective when both pitches are played on the same string. The chart below gives approximate largest tremolo intervals possible in lower positions by players with an average hand size.

Observe the notation below. Fingered tremolos should be marked with a slur, since several notes will be played with the bow moving in a single direction.

Alternating up- and down-bow strokes as quickly as possible produces bowed tremolo. Notated by placing three beams over the stem of the pitch, this technique is quite effective at all dynamic levels. For softer passages, it creates intensity and suspense, yet strings can play louder with this method of playing than any other. Swells, forte-pianos, accents, and other sudden or gradual dynamic shifts are possible as well. Bowed tremolo can successfully be applied to melodic lines as well as sustained tones, and it is possible to modulate from sul tasto to sul pont. without interruption, which CAN’T be done quickly with regular bowing. Bowed tremolos are usually played at the tip. Extended passages of this technique are fatiguing, and should be avoided.

GLISSANDOS.

Most pitched instruments are capable of performing some kind of glissando, a term that means “to slide.” For string instruments, this technique requires sliding a finger of the left hand up or down a string. Most types of glissandos are marked with a diagonal line from the first to second pitch; in addition, the word ‘gliss.’ may optionally be marked. Almost without exception, string glissandos should be marked with a slur, since they are usually performed in one bow stroke. Novice orchestrators often write glissandos that are too large, underestimating the

effectiveness of smaller slides. Though glissing up a 12th may be possible, such actions move into very high positions, ending on a pinched and strangled sound. Several kinds of glissandi are possible on string instruments:

Glissando on a single string. A smooth rise or fall from the first to the second pitch.

Glissando over more than one string. There will be breaks in the glissando as the

player switches strings, perhaps defeating the purpose of the gliss.

Fingered glissando. The fingered glissando entails playing a very fast chromatic run

with one finger. Not smooth, like a normal glissando, it entails quick shifting gestures in the left hand from pitch to pitch. Every note of the glissando should be written out under a slur. Very rapid bow changes synchronized with a glissando can create the illusion of a fingered chromatic run. Fingered glissandos are more feasible descending than ascending. They are effective when played by solo players. Performed by sections, this technique becomes blurred, canceling out the effect.

Glissando to a natural harmonic. A glissando, usually upwards, that begins on a stopped pitch and lands on a natural harmonic can be quite effective.

Natural harmonic glissando. A left hand finger, lightly touching a string, slides up and down. A series of the natural harmonics available on that string will sound. This technique, first used by Stravinsky, is most effective at lower dynamic levels.

Artificial harmonic glissando. Most commonly with touch-4 harmonic on a single string.

Pizzicato glissando. Most effective on the more resonant, lower string instruments, but possible on violin and viola as well. The starting and ending pitches may both be notated, connected by a slur. Alternatively, just the starting pitch and direction of the slidemaybewritten.

PORTAMENTO.

Sliding into a pitch for expressive purposes, is similar to a glissando, though the slide is softer, less emphasized, and rhythmically shorter. Some players add portamento intuitively, but to ensure its use, notate a short, diagonal line leading to the target pitch.