All Instruments | Effective Instrumental Writing

Effective Instrumental Writing

Extreme Orchestration

by Don Freund and David CutlerPublished: February 2024

COMPOSITION VS. ORCHESTRATION.

All composers deal with instrumentation and orchestration every time they write music. Even when composing for a solo player, it is imperative to know the potentials of the instrument at hand. Though some students of orchestration argue that they have no compositional ability, all orchestrators deal with composition. Even if the notes and rhythms have been provided, problems of orchestration must be approached creatively, and musical elements that did not exist previously appear. Both composers and orchestrators deal with pitches, rhythms, and expressive details, and both require a combination of craft and art. The role of composer and orchestrator intersect regularly; those terms are used interchangeably throughout this text.

There is a difference, however, between the two: composing entails the creation of new ideas, original successions of pitches and rhythms, and unique structural designs, while orchestrating determines how these ideas should be realized by a specific corps of instruments. Many composers always begin ensemble pieces by completing a piano reduction (short score) of their music first, and then orchestrating from this. Others combine the two steps, using aspects of orchestration as a central compositional impetus.

INSTRUMENTAL SOUNDS.

How many sounds can a woodwind quintet produce? To many, this question may seem absurd, almost condescending, with such an obvious response. Five, no? But upon closer observation we may draw a very different conclusion.

No instrument is limited to one single sound. On clarinet alone, for example, it is possible to hear low clarinet, mid-range clarinet, high clarinet, staccato clarinet, legato clarinet, sustained clarinet, loud clarinet, and soft clarinet. The list could go on and on. There are just as many sonic possibilities on flute, oboe, horn, and bassoon. Not to mention combination sounds, such as the flute and clarinet in unison or the horn and bassoon two octaves apart. It soon becomes apparent that this small ensemble of five players is easily capable of hundreds, or even thousands, of “sounds.” The number of sonic possibilities from an orchestra is virtually infinite.

When describing musical sound or timbre, analogies to color are often drawn. What are the most colorful sounds? Some might guess that combining flute, clarinet, trumpet, marimba, and violin playing in unison could produce an incredibly amount of color, since each instrument adds its own personality, but this is not the case. Just as combining many colors of paint will result in a gray or black, combining many instruments will cancel out the unique qualities of each. Featuring so many instruments may result in a thick, powerful sound, but as a rule of thumb, solo instruments project more unique colors than combination groupings.

However, context is the real determinant of the impact a color will have. If, in our painting analogy, most of the canvas were covered with pastels, with the exception of a single black streak, that may stand out as the most striking feature. The dense instrumental combination described above could be very striking following a long passage of solo statements. A single clarinet sounds much less colorful when draped over a backdrop of saxophones than it does when combined with a string choir.

Defining Character Through "Details"

Many composers spend weeks, months, or even years obsessing over notes and rhythms, but leave expressive markings and details until the last minute, treating them as superfluous features. Such a practice is unfortunate. While notes and rhythms supply the basic material and context for a composition, it is the expressive details that define character. By integrating these into the overall conception of a piece, a higher level of musical creation can be reached. Elements such as dynamics, articulations, inflections, techniques, descriptors, and register are essential considerations for effective (and outstanding) compositions and orchestrations.

DYNAMICS. While pitches and rhythms (and articulations to a certain degree) have literal meanings, dynamics are relative. There is not a single decibel level that constitutes forte. Instead, the appropriate loudness is determined by the context of the piece and the dynamics that surround it. Explain our dynamic system here.

Dynamics have a psychological impact on players. Players respond well to an expanded dynamic range from ppp to fff, sometimes ignoring or under-exaggerating dynamic markings such as p and mp. If softness is desired, pp or ppp is more likely to grab their attention. Musicians are more apt to respond to wide dynamic contrasts than subtle variations. For noticeable contrasts, skip at least one gradation. The difference between mf and f is negligible. Moving from mp to f or mf to ff will have a more dramatic impact. (Of course, when writing long, mapped out crescendos or diminuendos, successive single-gradation shifts may be necessary.) Use mf and mp markings with caution. These dynamics mean something only in relationship to others, and their overuse can result in middle-of-the-road music with a small range of dynamic expression. Think twice about beginning a piece with such markings. Though they are appropriate in many instances, a more extreme beginning might be to start on the loud or soft end of the dynamic spectrum. On wind and string instruments, indicate how sustained pitches should be shaped. Though it is possible for them to remain at a single dynamic, often such notes are more effective with a crescendo or diminuendo.

ARTICULATIONS. Articulations affect the attack and sustain of notes. Effective articulations are often the key to bringing a passage to life, and it is essential to consider the articulation of every note. Some orchestrators fall into the trap an “articulation area,” in which every note has the same marking. While such consistency may be appropriate, do not be afraid to mix and match articulations.

INFLECTIONS. Inflections are the ways in which notes are colored or decorated. This includes devices such as vibrato, trills, tremolos, grace notes, ornaments, and slides into designated notes.

DESCRIPTORS. While notes, rhythms, dynamics, and articulations give a good deal of information about how the music should be played, there are some performance aspects that are difficult or impossible to communicate through standard notation. Descriptors (adjectives) can be invaluable for describing the desired character of a given passage. Terms or phrases such as boldly, whispering, crunchy, like a bad joke, etc. give performers insight into the composer’s intentions. The more character the descriptor suggests, the more character the performance may incorporate.

VARIED PLAYING TECHNIQUES. Most instruments can be performed in a number of ways. For example, the strings of a viola may be bowed, plucked, or struck. Making resourceful use of the techniques available on each instrument can drastically increase the character of a passage.

REGISTER. Most instruments sound quite different in various parts of their range, not just because they are higher or lower, but because the quality of the timbre changes. Typically, instruments project a dark sound in their lowest register, while becoming increasingly bright as the pitch rises. Middle C is at the bottom of the flute range, and sounds rich and colorful. The same sounding pitch is extremely high, thin, and pinched for contrabassoon. When writing an orchestration, or even a solo instrument piece, consider exploiting the high, middle, and low registers of each instrument. An orchestrator, as we will see, has the right to shift passages from octave to octave as appropriate. Sometimes altering the register of just one or a few notes is an effective technique.

Writing Idiomatic, Playable Music

Outside of the physical limitations of each instrument, just about any passage is possible with the right performer and enough practice, regardless of difficulty. In fact, there are many examples in music literature, such as Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto, that were once deemed “unplayable” but are now part of the standard repertory. Composers like Brian Ferneyhough have made a reputation out of writing the most difficult music conceivable, yet many of their works have been successfully performed and recorded.

Brian Ferneyhough, String Quartet No. 2, performed by the Arditti Quartet

However, just because something is possible does not mean that it is practical or idiomatic. A very difficult passage feasible in isolation may become near impossible when strung together with a series of other acrobatic, unidiomatic challenges. And just because there is a player on the planet capable of your difficult music does not mean that your player will be able to execute the task. There is also a difference between writing solo/chamber music and large ensemble works. Smaller ensembles will often spend the time to work up difficult passages that would be unrealizable for an orchestra. Of course, challenging solo concerto parts or miniature solos within an orchestral piece are also feasible, but ensemble work may benefit from erring on the side of caution.

While some instruments are more adroit than others, they all lend themselves better to certain kinds of passages than others. Logically enough, players feel most comfortable performing music that is similar to the material they practice. For example, string players are reputed to be obsessive scale and arpeggio practicers. A passage that is scalar or arpeggiated in nature, even at very quick tempos, is more likely to be performed convincingly than one with frequent large leaps and string crossings or irregular melodic gestures. In addition to considering the comments regarding instrumental strengths and weaknesses in this text, orchestrators are encouraged to work with players to learn what works well and what hinders their technique.

Often, by slightly varying unidiomatic music (perhaps altering only a note or two), it is possible to make the passage exponentially easier to execute, while preserving the desired effect and essence. If equivalent results may be yielded, but one way is considerably easier to perform than another, why not opt for the player-friendly alternative? Idiomatic music will be performed more confidently. Although, as a composer, it is easy to become attached to the specifics of a piece regardless of playability, the level of confidence with which the ideas are projected is usually more significant than the particular notes for the listener. Don’t let ego prevent you from editing your music to make it more playable.

The authors of this book certainly have no intent to discourage you from pushing musical boundaries. On the contrary, extreme and creative orchestration is our primary concern. All rules were meant to be broken, and difficult or unidiomatic music may be necessary to achieve the musical goals of a composition. But there is obviously a price to be paid for such music— namely, it may not be played correctly or at all. Most of us do not have the world’s top performers at our disposal, eager to practice our creations ten hours a day. Determine what your objectives are for a piece, and use your understanding of the instruments, intuition, and imagination to capture these objectives in the most playable manner.

If only professionals would play my music...

Many inexperienced composers and orchestrators, frustrated that their difficult music is often not adequately performed, dream of the day professionals will finally flawlessly tackle their work. Though it can certainly be a wonderful experience to have a professional performance, there are a couple of shortcomings with this logic. First of all, the word professional simply that means players get paid. It does not necessarily imply they are better musicians than non-professionals. But even with top-notch professionals there is a hitch—since they get paid, and time is money, the player or ensemble will have a restricted amount of time to spend on your music if your financial resources are at all limited. To illustrate this point, major orchestras typically spend no more than three rehearsals to prepare for a full concert. That is not very much time to learn what might be 11⁄2 or two hours of music! In fact, non-professional, college, or community ensembles often perform a piece as well (or even better) than professionals. Because some college ensembles only perform one or two concerts per semester, they have more time to learn and internalize their repertoire than professional groups, even if the players aren’t as advanced.

The point of all this is that difficult music poses a challenge to all players, professional or not. If you are writing for specific performers, get to know their strengths and weaknesses, as well as how much time they will be able to devote to your music, and write with an appropriate level of difficulty.

To ‘Midi’ or Not to ‘Midi’

Composers and orchestrators today have one significant tool that was not available to Beethoven, Brahms, or Berg: MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface). MIDI allows computers and musical software and hardware to communicate with one another. MIDI can be extremely helpful. Playback is a cheap orchestrational tool for loosely checking timbral choices. It makes detecting mistakes (such as wrong notes or wrong rhythms) easier, and allows people to experiment with complex textures too difficult to perceive with the inner ear alone. However, this can be a mixed blessing. Many composers are tempted to rely on MIDI, thwarting their own imagination and ear. Some orchestrators won’t write anything that doesn’t “sound good” with this technology. While fast MIDI music can be somewhat convincing, slow passages are often unbearable. Because of this phenomenon, many young orchestrators are less adept at writing slow music. Many highly effective orchestral excerpts sound completely uninteresting electronically, while brilliantly executed MIDI passages may be unsuccessful with the orchestra. The “wind players” are never required to breathe, “percussionists” can switch instruments at the drop of a hat, and the balance is completely unlike that of an orchestra. Such playback does not illustrate the specific nuances, idiosyncrasies, or register characteristics of acoustic instruments, and while everything may be in tune and in time, it loses its humanity. When used well, MIDI can be a powerful learning and editing tool. When used poorly, it can inhibit the imagination. Like any tool, MIDI playback should be used carefully if desired, but not relied upon.

Other Considerations

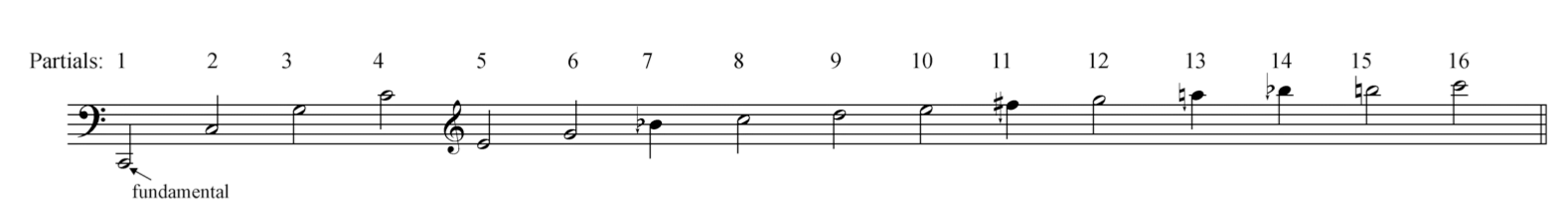

THE HARMONIC SERIES. Whenever a single “note” from an instrument is played, a series of higher pitches sound in addition to the main pitch, or fundamental. This natural phenomenon contributes to the timbral contrasts between instruments, as each timbre stresses a distinct combination of these partials, also known as overtones. Though the fundamental tone usually sounds substantially louder than the overtones, instruments such as chimes and gongs have such loud overtones that it is often difficult to discern the fundamental pitch.

Each partial of the harmonic series is always a fixed interval above the fundamental. Below is the harmonic (overtone) series built on a low C, followed by the first sixteen partials. Notice that some pitches are slightly flatter than we are used to hearing (shown by arrows attached to the accidentals).

When learning this series, keep in mind that doubling the number of a partial results in a pitch exactly an octave above. For example, partials 1, 2, 4, 8, and 16 are all C’s. Partials 3, 6, and 12 are G’s. Also notice that the intervals between the partials get smaller and smaller as you go up. Our perception of intervals in music is based on ratios, not absolute values. An octave is always physically created by the ration 2:1, whether it’s expressed in vibrations per second (440 Hz is an octave higher than 220 Hz), the length of a violin string (an open string 12 inches long will sound an octave higher if stopped at the 6 inch mark), or the amount of tubing in a brass instrument (the tubing of a piccolo trumpet is half as long as the tubing of a trumpet whose open fundamental is a octave lower). Acoustically, intervals are always created by the ratios identified by partials of the harmonic series: 3:2 is a perfect fifth, 4:3 is a perfect fourth, 5:4 is a major third, and so on. When these ratios are applied to frequency, string length, or tube length, the relative proportions will result in the interval associated with the ratio. Stopping a string one third of the way up from the open string will produce a pitch a perfect 5th above the open string, because the “new” string length is 2/3 as long as the open string. If a trombone slide is extended to make the tubing 25% longer than first position (a 5:4 ratio), the fundamental will be lowered a M3. With a little rudimentary math, you can use these ratios to calculate where all the pitches can be found on a string instrument and how the location of the nodes which create harmonics are related to the locations of the pitches. It is also easy to calculate how long the tubing needs to be in the valves of a brass instrument, and to realize why the slide positions on a trombone have to be further apart when a trigger makes the basic instrument longer. This means that finger positions on string instruments get closer together the higher one plays on the string, that woodwind registers get smaller as the pitch ascends, and that the fingering possibilities on brass instruments are increased the higher one plays on these instruments.

All instruments are affected by the harmonic series. String players can execute harmonics, actual higher sounding partials. Woodwind instruments are capable of harmonics to play in different registers. Most closely linked to the overtones are the brass; each fingering or position allows only the notes of one particular harmonic series to be played. With synthesizers it is possible to control the strength of each partial, or even create a very dull fundamental with no overtones, called a sine wave. When scoring, chord voicings sound natural and balanced when they follow the model of the harmonic series—larger intervals on the bottom followed by increasingly smaller intervals as the pitch ascends.

Transposition

If all the players of an orchestra or wind ensemble were asked to play middle C, a host of pitches would sound, rather than a unison. This phenomenon occurs because many instruments are transposing. In other words, the note they play sound different from the concert pitch (equivalent to notes on piano). Though concert scores and transposed scores are both common (discussed on p. ___), all parts must be transposed when given to performers who play transposing instruments.

Why do some instruments transpose?

Historically, some instruments were not capable of playing all the chromatic pitches. For example, early horns could only play the partials of a single harmonic series. If a piece were in the key of Eb, they would play an instrument based on the Eb series. Their parts were always written in C, and the only written pitches for these instruments corresponded with the notes in chart ___, eliminating the need to match a new set of pitches with the same partials of the series. E4, for example, always meant the fifth partial of the series, regardless of how it sounded on the given horn.

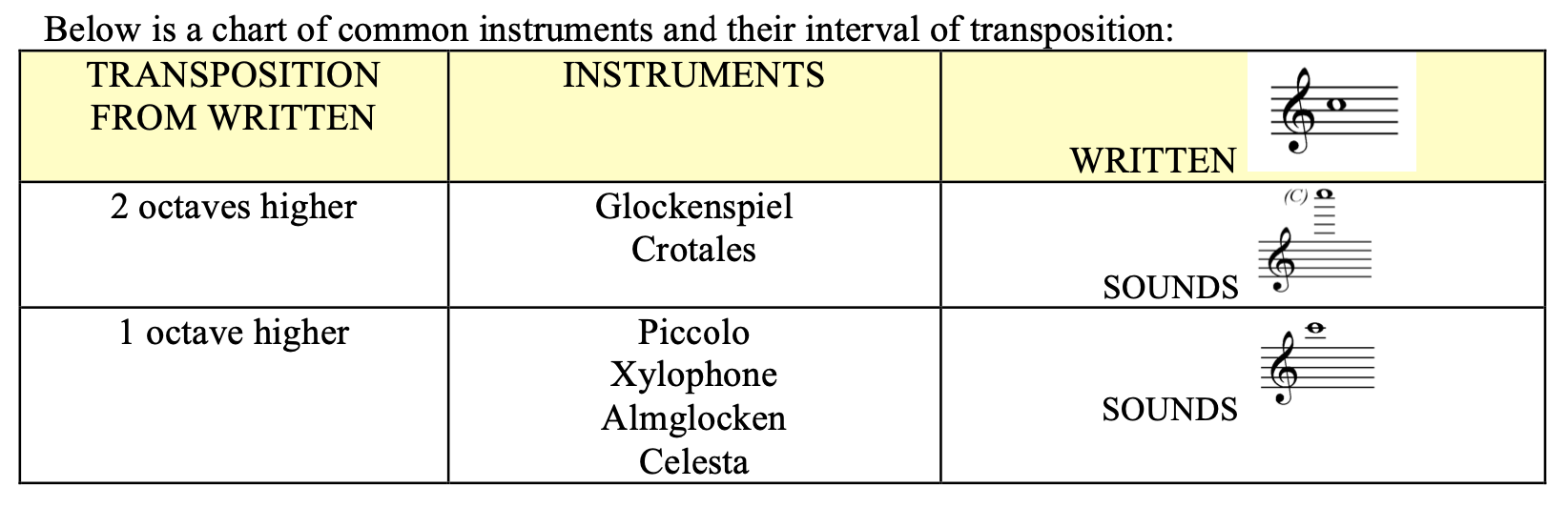

Though all transposing instruments today are chromatic, there are reasons for transposing in addition to this historical precedent. For most instrumental families, the fingerings and written range on all the instruments of that family are similar or identical. For example, a written middle C on any saxophone is played with the same fingering, though the sounding pitch differs. This allows performers to switch with relative ease from one instrument to another in the same family. Transposing instruments also avoid the need for excessive clef changes or ledger lines. Specifically, instruments with octave transposition allow performers to read from standard clefs while playing extremely high or low pitches.

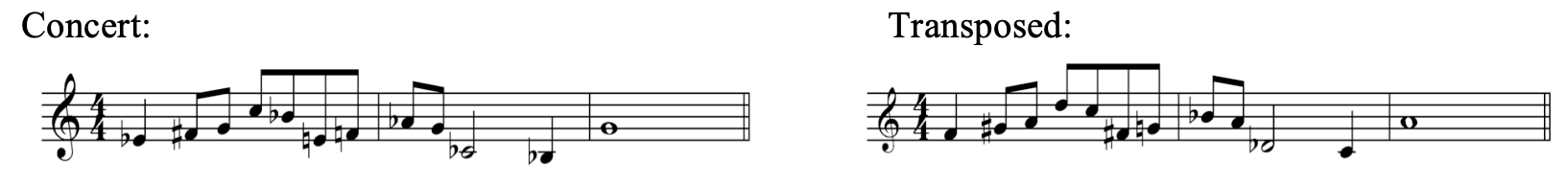

A majority of instruments sound lower than they are written, but high-pitched instruments (such as piccolo clarinet and glockenspiel) sound higher. A “Bb trumpet” receives the first part of its name because a written C sounds like concert Bb. All pitches sound a major 2nd (the interval between C and Bb) lower than they are written.

Notice that only the pitches with accidentals in the concert pitched example require accidentals in the transposed version. (However, they are not always the same accidentals; the concert E natural above turned into a transposed F#.) This is because the key signature is also transposed. However, music without a key signature (common for highly chromatic or atonal settings) is not treated like C major. When in C major, transposing instruments transpose the key signature, while music without a key signature will not show one in the transposed parts. This means that accidentals will often shift locations—be particularly careful when proofreading accidentals in such cases. Observe the example from above in a key signature-less setting.

TIP: To be sure you are not transposing backwards, always say “Written C will sound x.” substituting the transposing name of the instrument for x. For example, for Eb alto saxophone, say “Written C will sound Eb.”

Clefs

CLEFS. Instruments are generally assigned a clef that helps eliminate the need for excessive ledger lines. While common practice dictates that most instruments only read music written in one clef, some commonly alternate between two (or in rare cases three) clefs. The categories of clefs are:

Standard Clefs. Read by most instruments: Treble, Bass, Alto, Tenor.

Octave Transposing Clefs. Modified standard clefs, transposing the pitches up or down

one or two octaves. Shown by placing ‘8’ (one octave) or a ‘15’ (two octaves) above or below the clef: Treble 8va; Treble8vb; Bass8vb; Treble15ma.

Percussion Clefs. Used for instruments of indefinite pitch. Normally for non-pitched percussion instruments, but also possible when other instrumentalists are asked to perform non-pitched, percussive effects.

The chart below shows middle C in all the standard and transposing clefs and percussion clef.

Some transposing instruments, such as bass clarinet and baritone saxophone, are always written in treble clef, despite their low range. In concert scores, bass clef may be used, but transposed parts must always show treble clef. Similarly, concert scores may use transposing clefs for instruments with one or two octave transpositions, but their transposed parts should include only standard clefs.

Doubling

The term “doubling” has two meanings in music. As an orchestration device, it denotes that one instrument duplicates the line of another, creating a mixed color. But “doubling” can also mean that one person plays more than one instrument. The most frequent doublers of the orchestra are percussionists, who are often called upon to play a wide assortment of instruments. Also common is for auxiliary instrument doubling (such as flute/piccolo or piano/celesta). Less common doublings include switching between different instruments in the same section (trumpet and baritone or violin and viola), though Broadway and studio players often possess proficiency on a combination of instruments (sax, flute, and clarinet, for example). It is also possible to alternate between acoustic and electric versions of some instruments (such as bass). Curiously, no matter how many instruments are performed by one player, it is always called doubling; a musician playing flute, clarinet, bass clarinet, soprano saxophone, and alto saxophone is never called a “quintupler.”

Indicate on part all doublings that occur.

In smaller ensembles, doubling allows for a wider array of colors and more instruments than there are players. In larger groups, with multiple players in each family, convention dictates that the principal player remains with the primary instrument, while the other players may double.

How much time in needed to allow doublers to switch instruments?

Although doublers can often set down one instrument and pick up another relatively quickly (it’s always a bit unsettling to watch flutists juggle $10,000 worth of equipment on their laps!), players appreciate some extra time to allow their embouchures to reform to accommodate the change. When switching between instruments, leave at least five to ten seconds.

The Human Element in Orchestration

There is a temptation to think of the orchestra as a fabulous machine: the orchestrator inputs the notes, rhythms and dynamics and out comes the sound precisely as dictated. This false impression can be reinforced by MIDI playback. In reality, an orchestra is a society of artists applying their individual instrumental sounds and technical resources to the notated music in ways that they believe will contribute to the intended musical result. Orchestral players are trained to use their ears to make essential adjustments regarding intonation, balance, phrasing and rhythmic placement. It is traditionally each player’s responsibility to make their performance fit coherently with what they hear from the rest of their section, their choir, and the orchestra as a whole. Their sense of ensemble is guided by visual cues from their section leader and the concertmaster as well as the conductor.

The way in which orchestral music is conceived and notated must be empathetic to the ergonomics, psychology, and sociology of orchestral playing if it is to be performed most effectively. Practically all the information regarding notation, instrumentation and orchestration in this text is provided to help composers and orchestrators develop an informed sensitivity to this human factor, although no book can supplant the first hand experience of observing and participating in orchestra rehearsals and performances. Only if orchestrators provide the materials that give the players the opportunity to perform with effectiveness and conviction can they expect a satisfying and committed performance.

All Extreme Orchestration chapters

All Overview Pages

Effective Instrumental Writing

On This Page

Defining Character Through “Details”