Harp | Introduction

Harp

Despite its extreme expressiveness, harmonic potential, wide array of techniques, and the fact that it is the one of the oldest living instruments (cave paintings of the harp date back to at least the thirteenth century B.C. in ancient Egypt), the harp seems to strike fear in the hearts of many composers and orchestrators. As the only orchestral instrument that doesn’t have all of the chromatic pitches immediately available, it poses problems unique to the instrument, requiring a creative approach to scoring. Too many composers have shied away from harp explorations, resorting to only the simplest and most trite devices, or ignoring it completely—it is no coincidence that harpists themselves have composed a majority of the solo harp literature. Perhaps because so few composers have tackled the harp in a serious way, performers enthusiastically receive any well-written, creative music for their instrument. Along with these challenges comes an enchanting world of effects and timbres. With a bit of study and exploration, it is possible to demystify this beautiful, colorful instrument of the angels.

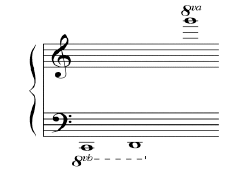

The modern harp, known as the double-action harp, has forty-seven strings, spanning over six and a half octaves. As can be expected, the strings are all different lengths, diminishing in size as the pitch rises. Before a performance, harpists must tune each of these strings individually with a tuning key. This can take ten minutes or longer. A harpist tuning on stage before the rest of the orchestra has arrived is not an unusual sight.

Harpists sit on a bench, with their head to the left side of the instrument and the harp resting on their right shoulder. The left hand can play throughout the entire range of the instrument. Because of the positioning of the harp, however, the right hand can only extend down to the pitch G2. Hands can easily cross over one another, but the left hand should not be kept above the right for extended periods of time. Only four fingers from each hand are available to pluck the strings, as the pinky is never used. Once the strings have been plucked, they ring freely until they stop vibrating or are actively damped. The lower strings naturally sustain longer than higher ones, which are substantially brighter and more percussive. For this reason, passages in the lower register can become quite muddy, roughly analogous to playing piano with the sustain pedal depressed. To dampen the strings, it is possible to stop the vibrations by pressing against them with fingers or an open hand.

Each octave contains seven strings, one for each letter name: C, D, E, F, G, A, B. In order to tell them apart, they are color-coded. Ordinarily, C strings in every octave are red, all Fs are black or purple, and the others are white. Such coloring is imperative, specifically for a passage that involves leaps. A performer must look at the strings, using the colors as points of reference. For this reason, there are times when it is impossible for a harpist to watch the conductor. Incidentally, harp is the only instrument that is virtually impossible for the blind, since there is no physical way to distinguish between the strings.

The strings are each attached to one of seven foot-pedals. The left foot operates three of the pedals, the other four played by the right. Each pedal corresponds to a different note letter name. The pedals are placed in the following order:

The pedals can be slid into one of three notches, altering the length of the strings.

Each pedal affects all of the strings with a given note name. For example, the D pedal changes the pitch for D strings in every octave; the F pedal alters all F strings. When all of the pedals are raised to the default position, the notes of Cb major are playable throughout the instrument’s range: Cb, Db, Eb, Fb, Gb, Ab, Bb. By shifting them to the middle slot, a C major scale is possible, and lowering all the pedals forms C# major. Of course, the seven pedals are independent of one another, so it is possible to combine sharps, naturals, and flats, making possible a large variety of typical and exotic scales.

If the A pedal is in the raised, flatted position, A-flat will occur in every octave. At that moment, playing an A-natural or A-sharp is impossible. For this reason, proper enharmonic spellings are critical. On the piano, or any other instrument for that matter, Bb and A# are played identically. They may have different musical implications, but no distinction exists in physically performing the notes. On the harp, the two pitches are played on different strings. Though they sound identical to a listener, to the harpist’s hands, A# and Bb are as different as Ab and B#. Double sharps and double flats may never be written for harp—notate these enharmonically.

While the harp cannot play all the chromatic inflections at any given time, every chromatic pitch is possible with the right pedal settings. In fact, all of the notes beside D, G, and A can be performed two ways. Below is a chromatic scale, including all possible harp spellings for each note.

To make matters just a little more complicated, three strings are not attached to pedals. The lowest C and D and highest G are not attached to pedal mechanisms. Before the harpist begins, these strings are tuned to either the flat, natural, or sharp version of the pitches. They must remain that way until the harpist physically retunes the string with a tuning key.

These strings are not affected by pedal changes, and must be tuned to the proper accidental before beginning.

Sight reading on the harp is arguably, more difficult than on any other instrument for one reason alone: pedaling. If frequent pedal changes are required, accurate sight-reading is, for all intents and purposes, impossible. Once the performer has gone through the score and marked in the changes, reading becomes comparable to other instruments. It is not uncommon to distribute all the parts for an orchestral piece weeks in advance, and then learn that only the harpist has worked through it. If you are working against a deadline, and will be able to produce parts only days (or even hours) before a reading, consider producing the harp part first.

The most critical aspect of harp writing, and perhaps most confusing, is keeping track of pedal settings, and in turn, which notes are possible when. For largely diatonic music, or excerpts that stick with the same set of seven pitches for an extended period of time, this is not a problem. But when writing complex, atonal figures, frequent modulations, or music for multiple harps, it is more than most people can visualize in their mind. The Pedal Simulation Diagram (P.S.D.) outlined below is easy to use, and it only costs less than a dime.

On a piece of paper, write the pedal names from left to right: D, C, B, E, F, G, A.

Put a line between the B and E, separating left and right pedals.

Above each of the letter names, write a flat. Below each of them, write a sharp. All of the pedal settings are now clearly drawn. It should look like this:

4. Scrape up seven pennies from your piggy bank. Place them slightly to the right of each pedal. As your pedals changes, move the pennies. You now have a simple, foolproof way of keeping track of pedal positions.

There are two ways to indicate a given set of pedal positions to a harpist. The first way uses letter representation. The pedals are listed in order, and the left-right break is shown with a ‘/.’ The second, and preferred, method is to include a pedal diagram. A pedal diagram is a visual representation showing where the pedals should be positioned. Either representation should be written above the top staff, or below the bottom one, but not in between the two. The letter representation and pedal diagram below indicate identical pedal settings.

Pedal changes are not physically difficult to make; they are a regular part of harp performance. Up to two pedal changes at a time are possible, but the pedals must be operated by opposite feet. For example, it is feasible to move from B-flat to B-natural and G-sharp to G-flat simultaneously. It is not possible to change from B-flat to B-natural and C-sharp to C-flat at the same time, since both pedals are operated by the left foot.

As stated, all but three notes in the chromatic scale are possible to play two different ways. When determining which enharmonic to use, use you P.S.D. and think logically through the passage. Sometimes spellings on the harp look odd, perhaps finding it necessary to spell a Bb minor chord A#, Db, E#. A piece that requires regular or constant pedal changes is a nightmare for the harpist, even if all changes are possible. Such a score would require hours upon hours of practice. Though it is possible to reset even all seven of the pedals in a relatively short amount of time (three to four seconds?), such requirements should not be frequent. The number one harp pitfall to avoid, besides writing impossible pitches, is overburdening the performer with too many pedal changes.

Rarely, if ever. As a composer or orchestrator, it is crucial to be aware of pedal changes. But every harpist has individual preferences about where to make the pedal change and how it should be written. Use enharmonic spellings to indicate logical pedal changes, but let harpists write the actual changes in the score.

There are some exceptions to this rule. It can be helpful to indicate the pedal settings:

1) at the beginning of a piece or phrase;

2) when changing pitches during a glissando..

One final aspect of pedal changes should be kept in mind. Pitches played on the harp are resonant. Depending on where they occur in the range, some pitches sustain for a substantial amount of time. If particular note is sustaining, and the pedal position is altered, a change of pitch on that string may be audible, regardless of the octave.