Percussion | Introduction

Percussion | Introduction

Extreme Orchestration

by Don Freund and David CutlerPublished: February 2024

For centuries, the orchestral percussion section was the least developed, rarely employing much more than timpani with occasional snare drum, triangle, and cymbals playing simple parts suggesting Turkish influence. The same section today draws from literally hundreds of instruments, limited only by the imagination of the composer. It has borrowed and/or modified instruments from virtually every culture, and even includes everyday items, such as washboard, automobile horns, wind chimes, and police whistles. Because so many instruments are available, most organizations regularly rent equipment that they don’t have in their arsenal to fulfill the requirements of the literature they play. Whereas most string or wind players approach an unfamiliar instrument with suspicion, if at all, percussionists are regularly required to concoct new structures for music making.

Though percussion instruments can be pitched (such as marimba, xylophone, and timpani1) or non-pitched (such as snare drum, triangle, and cymbals) there is often a fine line between these two categories. Many non-pitched instruments produce discernable “notes,” and come in a variety of sizes, with larger instruments sounding lower, deeper, and darker than smaller ones. On the other hand, a few pitched percussion instruments (such as chimes and gongs) elicit so many partials that it is difficult to make out the fundamental clearly.

Percussion instruments can be made of wood, metal, animal skin, strings, or other materials. They may be set into vibration by being struck, shaken, scraped, pushed, squeezed, cranked, blown, or by other means; most instruments can be played via a number of techniques. Some have little or no sound beyond the initial attack, while others sustain for extended periods of time. Playing more than one percussion instrument simultaneously may be possible. The percussion section can be used to set up a rhythmic pattern, emphasize an articulation, add drama, create a sonic backdrop, suggest exotic musical styles, provide accompaniment, or present a melody. Though percussion instruments have a reputation of being loud, they can also be one of the most delicate and subtly colorful sections of any ensemble. Using these instruments tastefully can add magic to a score, though overusing them can easily become annoying and mateurish. With so many possibilities, it is no wonder that composers have explored and exploited percussion instruments in such a wide variety of settings. These possibilities also pose a number of challenges to the orchestrator.

It is crucial to consider logistical concerns when one performer is required to play multiple instruments. For example, it is possible to switch quickly from xylophone to snare drum—if they are located close to one another, if the player uses the same mallet type. If not, rests must be included to enable the shift. Obviously, not all of the instruments can be in close proximity in a large percussion battery. Music with quick shifts between different instruments requires that they be strategically placed. Delicate passages are difficult to execute if a performer is required to make quick, jerky motions just to locate the instrument.

Trick of the Trade

When requiring percussionists to play a medium or large variety of instruments, it is a good idea to make several copies of their music. By placing scores on two or three music stands spread throughout the setup, the need to reposition their part while playing is eliminated.

It is helpful to include a percussion diagram in scores, illustrating where the various instruments should be positioned. If few instruments are required, they can be placed around the standing player, but larger and more complex forces require creative planning. It may be necessary to have two rows of percussion, with lower-positioned instruments closer to the player. Mallets and instruments held in the hand are often set on small trap tables covered with towels, while drums, cymbals, gongs, and others can be suspended. Making a diagram not only aids the percussionist, but it forces the orchestrator to consider logistical concerns.

It is certainly possible, depending on positioning, for multiple percussionists to share an instrument. However, this practice can cause congestion, and is not recommended. An effective alternative is to have multiple versions of the same instrument located on different points of the stage. This eliminates the need to share equipment, and creates a marvelous antiphonal effect.

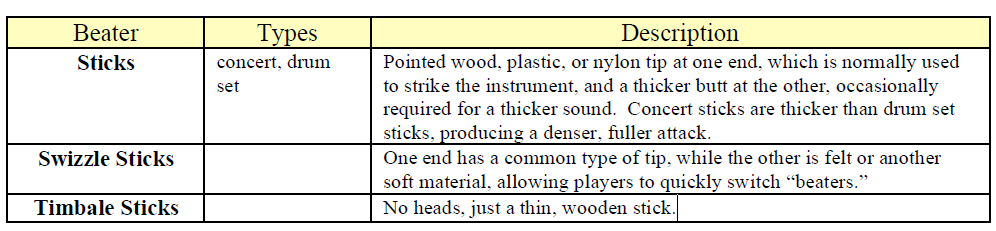

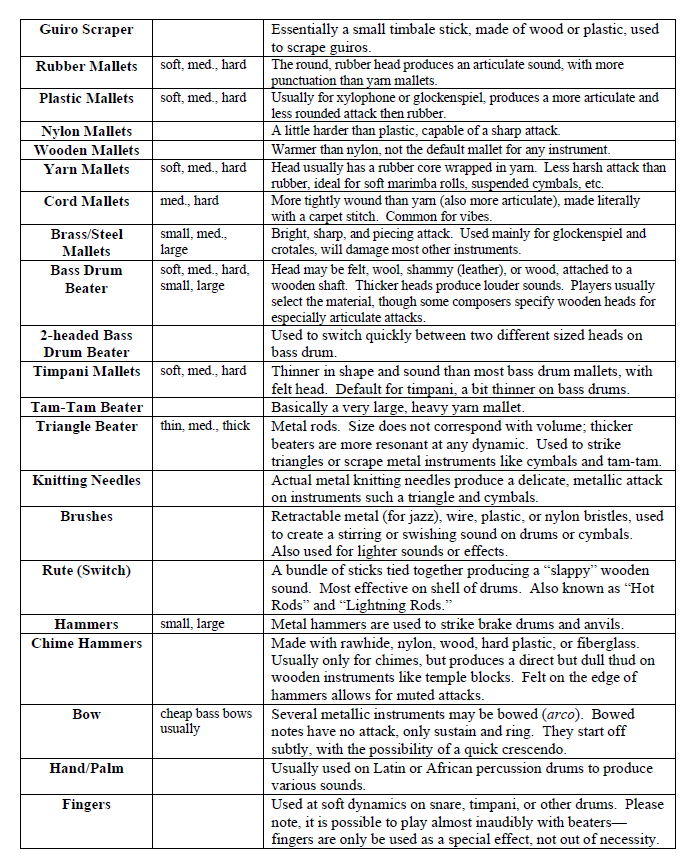

Beaters

A majority of percussion instruments are set into vibration when struck with beaters. The material and hardness of the beater has a drastic impact on the timbre of the instrument. Hard beaters have a percussive and direct attack when compared to softer, mellower ones. The shapeof the tip and the size and weight of the beater also affect the attack and color. By flipping the beater around, a new kind of material may become quickly accessible, since the butt (back end) of a beater is often a different thickness, or made of an alternate material, from the tip (front end). Scores should be meticulous about including the desired type of beater, especially if the default sort is not preferred. If uncertain which type to use, include a few words describing the desired sound (“in the distance,” “sharp and pointed,” etc.) Normally the same type of beater is held in both the right (R) and left (L) hands, but holding different kinds of mallets in each hand is also possible. Some music, particular for mallet percussion, requires more than one beater in each hand. It takes at least a second or two to switch beaters, so be sure to include leave time for the switchover in the score.

Though the list below describes many types beaters, the only way to internalize their affect is by listening to them on various instruments. It is helpful to ask percussionists to play a single passage with several different beaters to grasp the individual nuances.