Woodwinds | The Bassoon Family

Woodwinds | The Bassoon Family

Extreme Orchestration

by Don Freund and David CutlerPublished: February 2024

Bassoon

Contrabassoon

THE BASSOON FAMILY.

The bassoon family is limited to the bassoon and contrabassoon. Since these are double reed, conical bore instruments, basic acoustics might suggest that they should be included in the oboe family (or that oboes be included in the bassoon family since bassoons arguably arrived first). The sound quality of bassoons, however, differs significantly enough from the oboes to merit a family of their own. Bassoons are less nasal, more relaxed in character than the oboe family members, due (among other things) to their folded-back bore construction and thickened, angled tone holes. The basic construction of the bassoon suggests a G2 fundamental, so that much of its length is a somewhat clumsy "add-on." As a result the tone is generally more veiled and melancholic.

The bassoon's double reed is placed on a thin curved metal pipe called a bocal (also used by the English horn) that attaches to the top joint of the instrument. Shortening or lengthening the bocal allows bassoonists to adjust the basic pitch in a way not available to oboists, but bassoonists share the oboists' devotion needed to make and fine tune their double reeds. Bassoonists are also faced with the most intricate fingering system in the woodwind world. The arrangement of tone holes and keys on the bassoon, and indeed the structure of whole instrument, is evidence of an instrument that evolved over time. The result is the most idiosyncratic among standard orchestral instruments, affecting not only the way it is played but also its particular sound in a way that is uniquely resistant to simplification. The contrabassoon, though slightly more "modern," shares or even amplifies these idiosyncrasies.

Both bassoon and contrabassoon are written as C instruments. The bassoon is untransposing, while the contrabassoon sounds an octave lower than written. It is becoming more common to write the high register of the bassoon in treble clef, although tenor clef is still preferred. Bassoonists are accustomed to reading bass clef with ledger lines as high as B4.

THE BASSOON: A GUIDE TO THE REGISTERS.

The curious design of the bassoon's bore and tone holes result in a wonderful, if motley, array of "mini-registers." The lowest 5th of its range has a veiled, dark sound that is difficult to control for quiet attacks or delicate dynamics, although the bassoon's lowest notes are not as coarse and problematic as the oboe's. The 12th from G2 to D4 is the heart of the bassoon's range, and is generally the most flexible range for color and dynamic variation. However, the 4 pitches from D3 to F3 are more nasal, the most oboe-like on the instrument, and F♯3 is difficult to match timbrally. The register above D4 gets weaker and more strained as it ascends, and pitches above C♯4 are very difficult to project, variously described as pinched or strained. Composers reaching for a forceful bassoon sound may be disappointed with anything above A4. Articulation is especially clear in the middle register, but the bassoon has a clear, incisive attack in all but the most extreme ranges.

BASSOON STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS.

The bassoon has the narrowest dynamic range of the woodwind section, and its potential for color variation is limited. Its timbre, however, is almost always attractive, contributing a welcome warmth, clarity, and substance in almost any musical context. It functions admirably as the bass instrument of the woodwind section, and adds strength and clarity when doubling cellos and/or basses. Using the bassoon to double violin melodies an octave or two below is a staple of Classical and Early Romantic orchestration. It has a graceful simplicity of articulation and projection in faster moving melodic lines, and a wonderfully plaintive, even foreboding quality in longer lyric passages. Using the bassoon as a soloist can bring a fresh perspective to a musical statement.

Fast single tonguing is perhaps clearer and more effective on the bassoon than on any other wind instrument, and double and triple tonguing is available to some players. The lowest fifth is not as agile as the rest of the instrument, and notes in this range need to be attacked firmly. Fingerings become cumbersome above G4. In general, fingerings in flat keys are more facile on the bassoon than sharp keys.

There are more limitations on trills and tremolos on the bassoon than on other woodwinds. Conservatively speaking, one should avoid all trills below G2, above A4, or trills involving any D♭, E♭ or G♭.

“The Clown of the Orchestra”

With apologies to bassoonists everywhere, it must be noted that no discussion of the bassoon can be considered complete without resorting to this characterization. Actually, it’s a great compliment to the instrument, attesting to the phenomenal incisiveness of its articulation, its ability to leap registers rapidly, and the facility of its slurring and passage-work, even though its way of responding to these challenges can sound slightly ungainly. It is also true that the somewhat erratic mix of colors that tend to pop from the instrument in fast passages are amusing, but this possibly awkward play of colors is what gives slower lyric lines their tender pathos

THE CONTRABASSOON.

The contrabassoon is even odder looking and more awkward sounding than the bassoon, but it occupies a grand position as the great bass of the traditional orchestra. Its most conspicuous virtue is an ability to play lower than any instrument in the orchestra except the piano, which surpasses it by only one semitone. More impressive is the way it makes those low notes sound, with a rattle and gravity that seem to shake the hall even if, in reality, it isn't terribly loud. The contrabassoon is twice as long as the corresponding contrabass clarinet, resulting in a noticeably slower response as the sound wave passes through the twists and turns of its bore. Its main function has been to double the bassoon an octave lower (like an organ's "16-foot stop,") but it can anchor a bass line by itself in passages of mf or less. The contrabassoon is capable of some surprising agility in articulation, passage-work and skips, though less so than the bassoon. It is rarely used as a melodic solo instrument, but lyrical passages, though hoarse and disembodied, can be remarkably effective even when written above the bass clef, although this range is rarely called for. The contrabassoon has a marvelous ability to combine with bass clarinet, bass trombone, tuba, and/or string contrabasses to add clarity to low muddy passages. Written F4 (sounding F3) is the highest practical note for contrabassoon, although virtuoso solos may reach for written B♭4.

THE BASSOON SECTION.

Around the turn of the 20th century, composers routinely asked for 4, even 5, bassoons in their orchestrations. Today, even with professional orchestras, a section of three — two bassoons and a contrabassoon — should be considered to be the limit.

Bassoon Family Orchestral Examples.

Here are examples from orchestral literature that demonstrate characteristics of the bassoon family.

EXCERPTS FOR BASSOON.

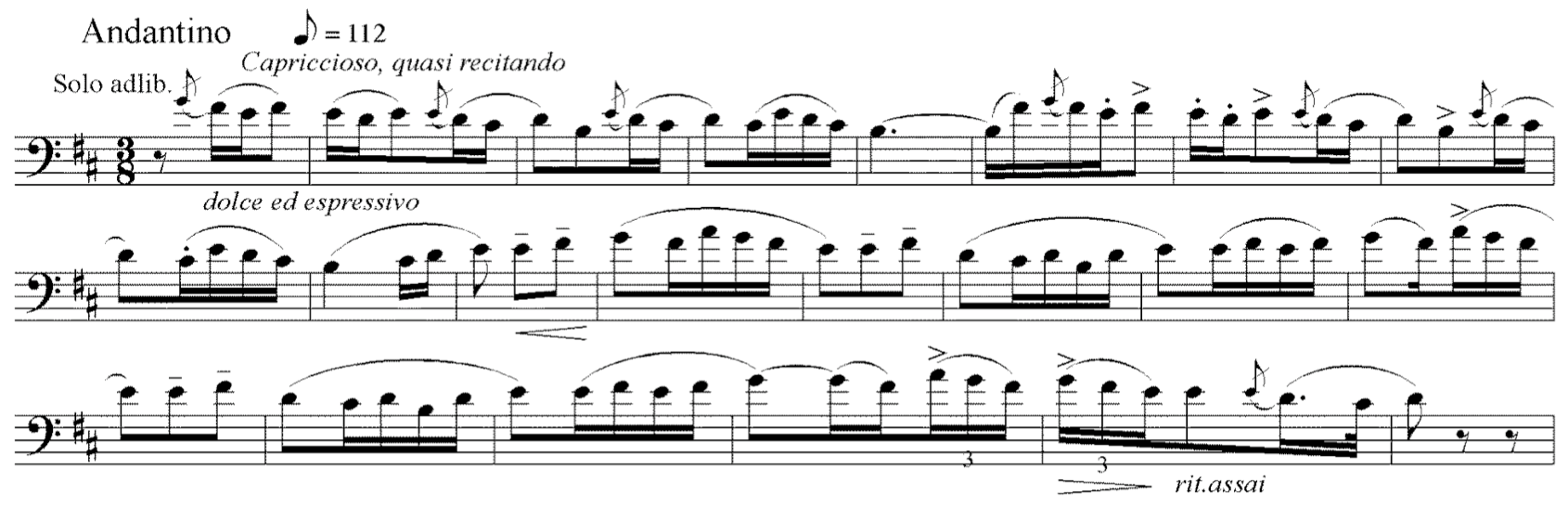

Mozart: Marriage of Figaro Overture, m. 101-115. This passage begins with the bassoon in a solo role, standing in relief from the string chords by virtue of its staccato articulation. Then at m. 108, in a singing style it doubles the violin melody an octave lower. Mozart avoided the A4 in m. 112, but most bassoonists will take the lower A up to match the shape of the violin melody and to revel in what might be considered the bassoon’s highest full-throated note.

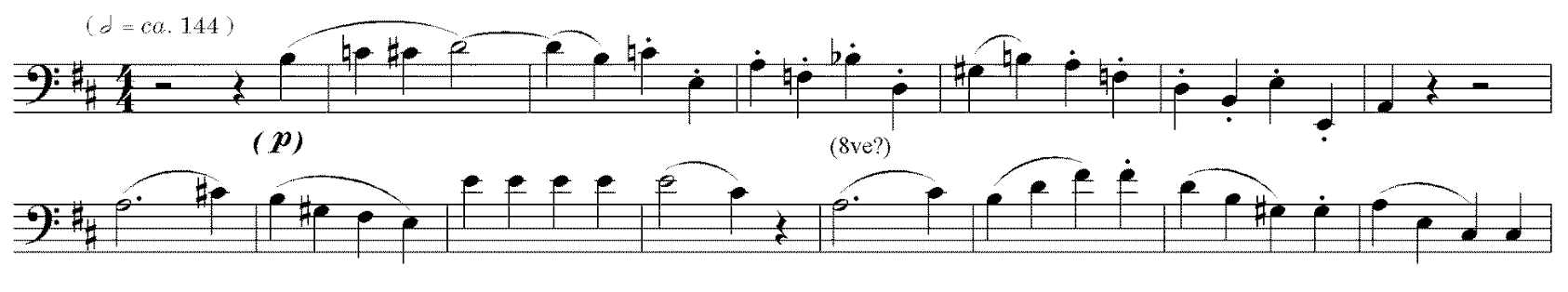

Rimsky-Korsakov: Scheherazade, 2nd Movement, m.5-26. This solo features grace-notes and copious articulation information, but its overall character remains seductively lyric. It is accompanied by 4 solo string contrabasses and written in the bassoon’s most expressive range, using bass clef with ledger lines.

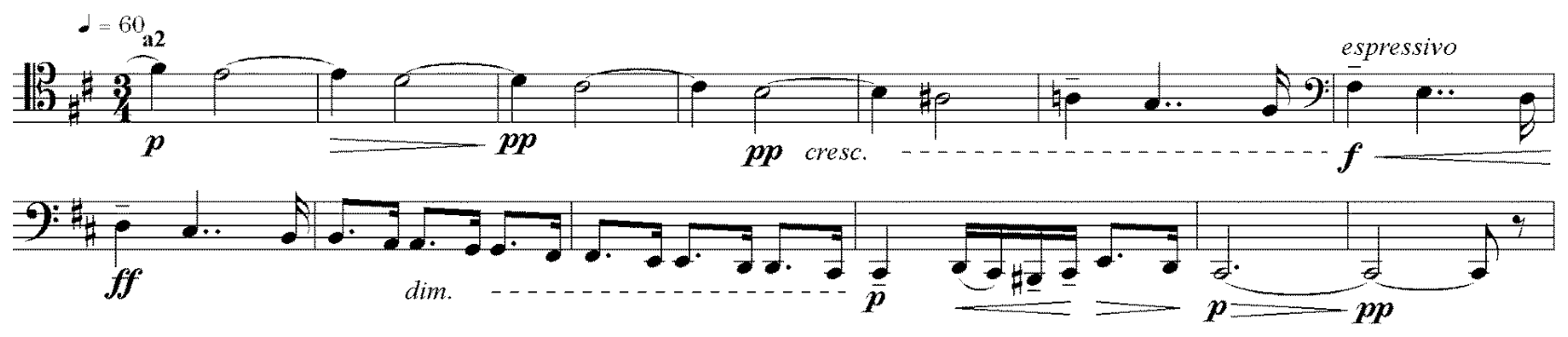

Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 6, 1st Movement, m. 1-6; 4th Movement, m. 30-36 . This excerpt shows the expressive, dramatic power of the lower range of the bassoon; the two bassoons a2 gradually become the protagonist, against low strings and low 2nd horn.

Stravinsky, The Rite of Spring. "The Rite of Spring" begins with this high solo, at first unaccompanied, then joined by mp horn and p clarinets. Stravinsky gave no dynamic to the bassoon, presumably believing that the bassoon in this register is fairly limited in dynamic range and color. Compared with the Scheherazade excerpt above which has a tessitura a 4th lower, this passage sounds appropriately unearthly and mysterious.

Stravinsky: Violin Concerto, 1st Movement, rehearsal number 22; 4th Movement rehearsal number 108. Here Stravinsky uses the lowest range of the bassoon, cutting through the orchestra with sharp staccato articulation.

Brahms: Symphony No. 1, 4th Movement, m. 164-184. Here Brahms uses the contrabassoon in its traditional function, adding definition to the string contrabasses, who in turn are doubling the cellos an octave lower. The low C is an octave higher in the contrabass part — the 2-octave leap appears only in the contrabassoon.

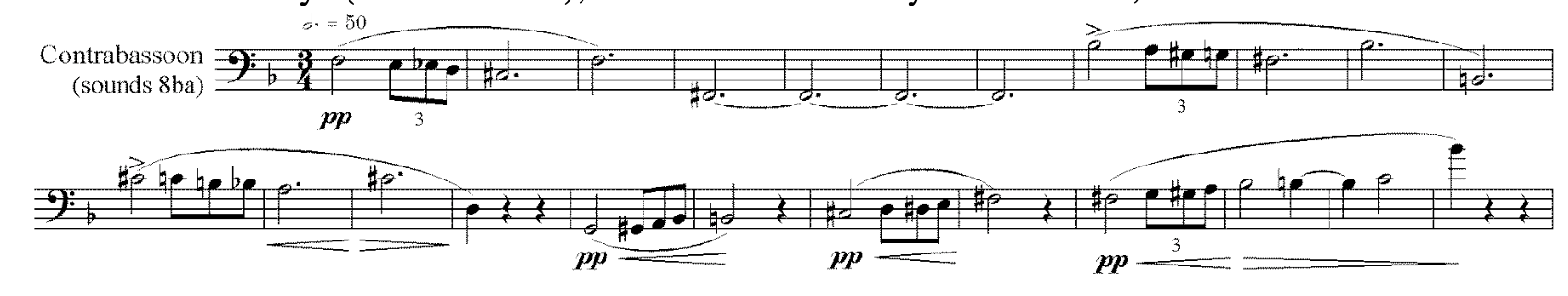

Ravel: Ma mère l’Oye (Mother Goose), 4th Movement “Beauty and the Beast,” rehearsal number 4-5. The contrabassoon is an obvious choice for Ravel’s characterization of the “Beast,” but the composer’s special orchestral genius can be heard in the instrument’s ungainly elegance as it sings through the skips and sweeps of Ravel’s waltz. The concluding skip up to the high B♭ is extremely treacherous.

The contrabassoon is an obvious choice for Ravel’s characterization of the “Beast,” but the composer’s special orchestral genius can be heard in the instrument’s ungainly elegance as it sings through the skips and sweeps of Ravel’s waltz. The concluding skip up to the high B♭ is extremely treacherous.