Woodwinds | The Clarinet Family

Woodwinds | The Clarinet Family

Extreme Orchestration

by Don Freund and David CutlerPublished: February 2024

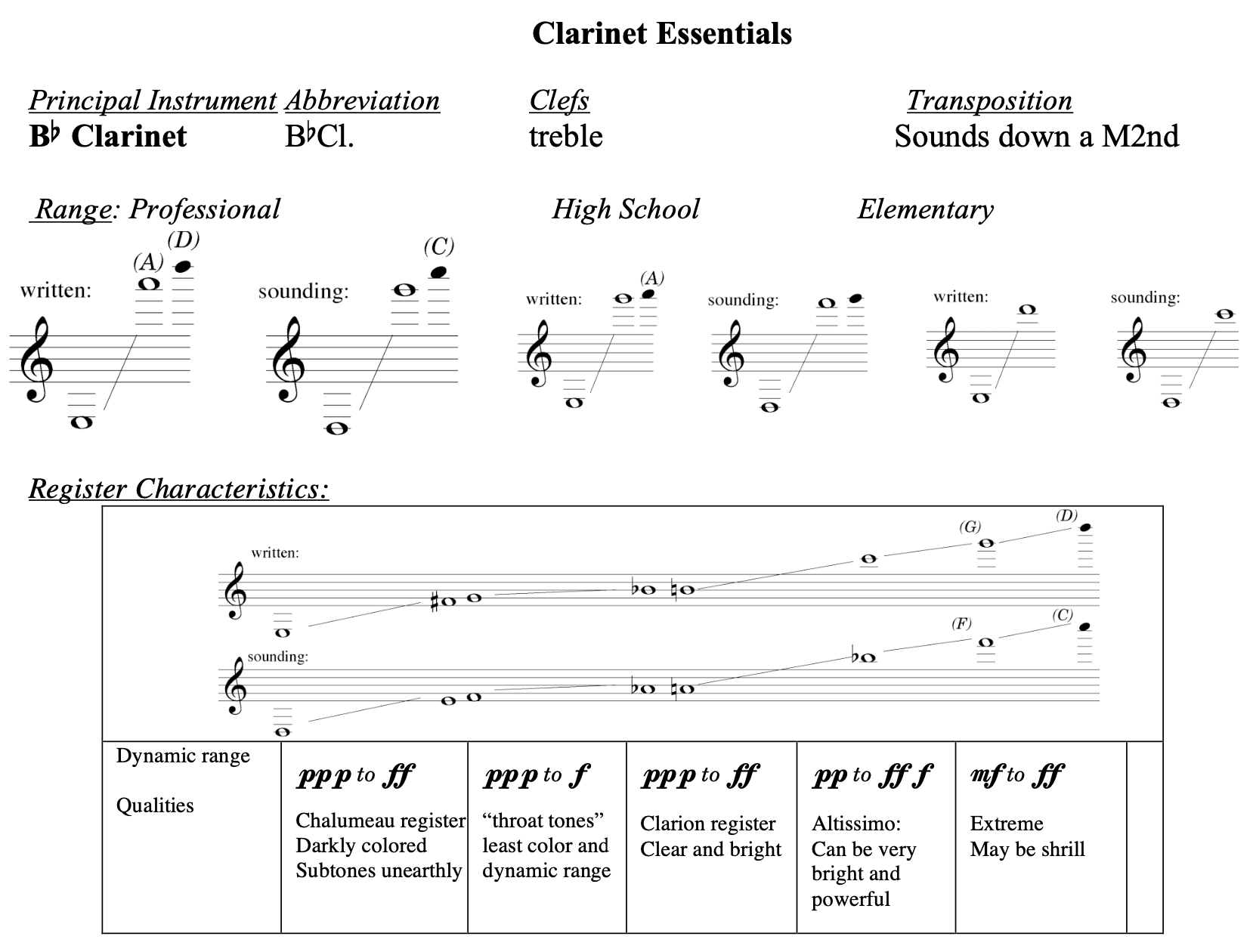

THE CLARINET FAMILY.

Clarinets are the most prevalent of all woodwinds, despite the fact that they were the last to become standard members of the symphony orchestra, near the end of the Classical Period (saxophones are still waiting). There are many good reasons for this. Its broad range allows it to be a tenor, alto, or even coloratura soprano member of any ensemble. Its dynamic range practically doubles that of all other woodwinds except saxophones, and this dynamic compass is available throughout the entire standard range of the instrument. Its capacity for virtuoso display and heart-throbbing lyricism easily rivals any other instrument. No other woodwind family has so many upward and downward range- extending auxiliary instruments; the total range of the clarinet family nearly matches that of the entire orchestra.

All clarinets are cylindrical bore, single reed instruments, physical properties that result in a dominance of the odd partials of the harmonic series in the basic tone color. The third partial, sounding a p12th above the fundamental pitch, is especially strong, giving the clarinet its characteristic smooth, hollow sound. This acoustical phenomenon is also evident in the fingering of the instrument, due to the fact that the clarinet overblows at the 12th. Its bottom register covers 19 pitches in half-steps before the register key allows the fingering to begin recycling. Thus, pitches from written B4 to C6 have standard fingerings which match pitches a 12th below, utilizing the 3rd partial of those fundamentals in a way similar to what are called "harmonics" on the flute and oboe. As a result, the registers of clarinets show a much greater diversity of colour than is found on other wind instruments.

THE CLARINET: A GUIDE TO THE REGISTERS.

The striking difference in the colour of the two main registers of the clarinet accounts for the descriptive names always used when describing them. The chalumeau register, so called because it mirrors the colour of the chalumeau, a medieval cylindrical bore single reed instrument, extends from written E3 to around F4. This register is where the predominance of the 3rd partial is most obvious, creating a wonderfully dark, rich, but hollow quality. The next higher 4 or 5 pitches, called "throat tones," are notoriously the least colorful portion of the range of the instrument, but instrument design and the technique of good clarinetists have gone a long way towards minimizing this pocket of dullness. The same can be said of the potentially treacherous "break" between written B♭4 and B4, a major preoccupation in traditional orchestration texts, which no longer seems to be a matter of much concern. The name clarion (or "clarino") is applied to the register that begins upward from C5; this name is also borrowed from an instrument, a Baroque trumpet. In fact, the word "clarinet" is simply a diminutive form of this name. The clarion register is bright and clear. From written C♯6 upward the tone becomes more difficult to modulate, and beyond G6, considered the top of the "normal" range, the quality is shrill and piercing.

CLARINET STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS.

The ability of the clarinet to play extremely softly and loudly throughout its range makes it a tremendous multi-purpose resource for the orchestrator. Attacks can begin so quietly that they are virtually inaudible, indicated by "niente" (nothing), followed by a crescendo to any dynamic level the composer wishes. Reversing the process to release niente works equally well. Passages may be played on the threshold of audibility, marked "echo tone," "subtone," or simply ppp. This technique is especially effective in the chalumeau register, but can be used in all but the highest register. ff in the chalumeau region can surpass the volume of the oboe (though not a brass ƒ), and the clarinet in the clarion register and above can overpower a flute.

Throughout its range, the clarinet needs less air to produce a full sound than the flute does, so it can sustain relatively long notes and extended melodies on one breath. On the other hand, air flows more freely than on the oboe.

Articulation on the clarinet is almost as versatile as the flute, although double tonguing, triple tonguing, and flutter tonguing are less idiomatic and not as common. Since a tongued note does not kick into full volume as immediately as on the oboe, clarinet articulation is not naturally as incisive, but the large dynamic range of the clarinet makes sforzatos and forte-pianos particularly effective.

Composers can expect a great deal of virtuosity from professional clarinetists. The instrument responds very well to fast passages, and because it can maintain a dynamic posture over a large range, fast scales and arpeggios covering multiple octaves sound idiomatic. Trills and tremolos are very playable and effective excepting those in the extreme high range. Downward leaps of a 10th or more are nearly impossible to slur on a clarinet, but slurring large skips upward is not a problem.

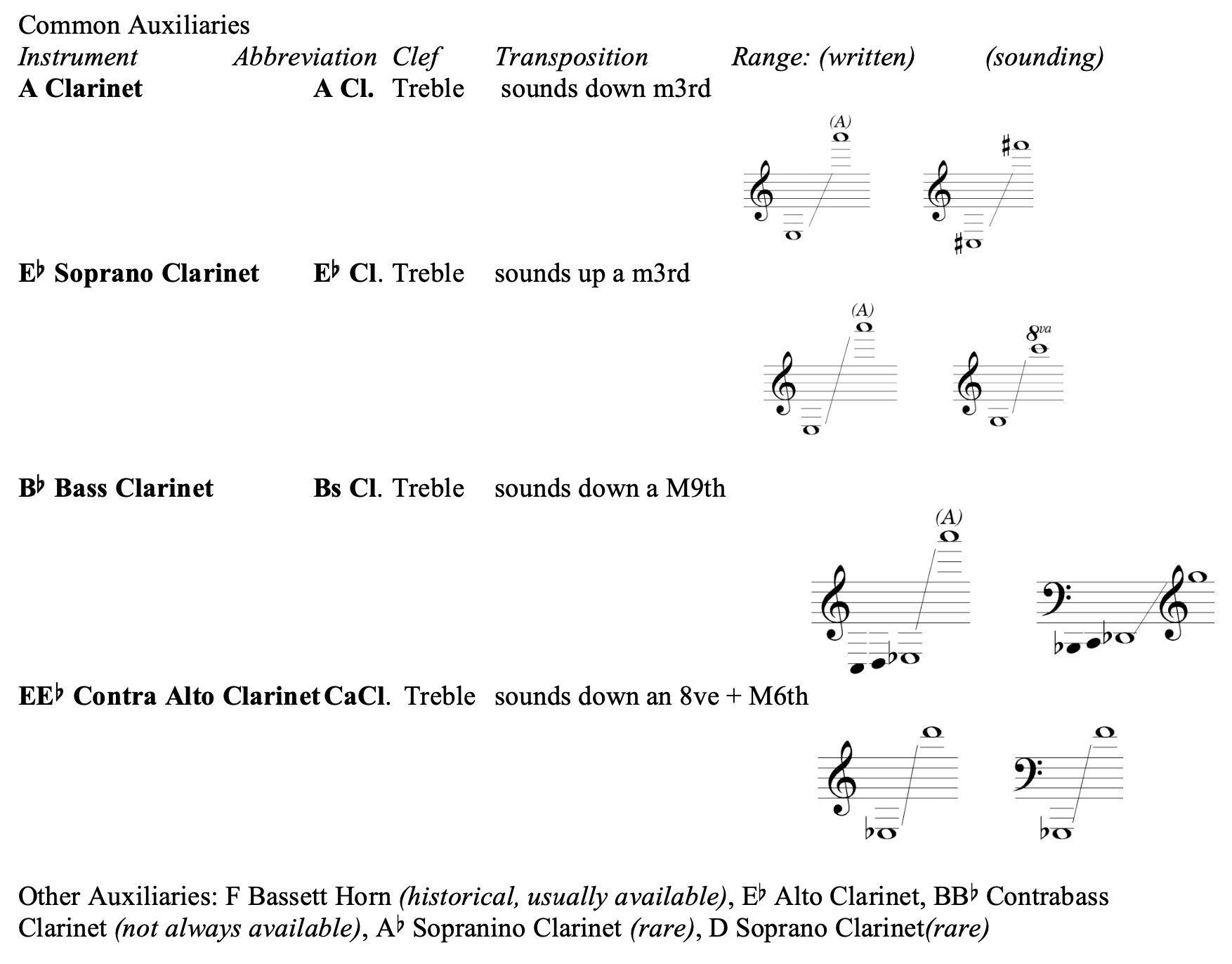

THE BB CLARINET AND A CLARINET.

Both of these instruments are considered the "principal" instruments for the clarinet family, and in the orchestra they have both have received equal attention until midway through the 20th century. It made sense to have two different clarinets, one for flat keys and one for sharp keys, in the days before improvements in the fingering system made these issues a moot point. Late Romantic scores frequently call for clarinetists to double on both B♭ and A clarinets, following the tonal meanderings of the music, and most professional clarinetists own one of each. The B♭ clarinet is the mainstay of bands and is becoming the "default" clarinet for most recent orchestra, wind ensemble, and chamber music. Since the B♭ is more widespread, most composers write for it, though the A clarinet does allow for writing a concert C♯3, while sacrificing some higher notes. Opinion differs on whether there is a significant difference in sound between these instruments; it is possible that those who claim a decided preference for the sound of the A clarinet are simply cheering for the underdog. Unless the composer has a particular fondness for the A clarinet, or can't live without the C♯3, it is recommended that the more common B♭ clarinet be used.

THE EB (SOPRANO) CLARINET.

Just as the principal clarinet may be in B♭ or A, the "piccolo" (or "soprano" or "sopranino") clarinet parts have been written for both E♭ and D instruments. In this case, however, the D version is hardly ever used; in modern orchestras these D clarinet parts are transposed and played on the E♭ instrument. This instrument has been typecast as having a grotesquely bright, mocking, extroverted character, due to famous solos in Berlioz's Symphonie Fantastique and Strauss's Till Eulenspiegel's Merry Pranks. This is not totally inappropriate: the E♭ clarinet (the accepted generic name) has little of the B♭ clarinet's warmth and mystery in the chalumeau register, and its clarion register is definitely brighter than its lower sibling. It also has a greater resistance to its airflow, using breath more like the oboe, and has a correspondingly sharper, more incisive attack than the main clarinet. Nonetheless, it shares the clarinet's extensive dynamic range and technical versatility, and fills the need for an extra wind instrument that can play high expressively, up to concert B♭6, offering an alternative to the piccolo and high flute.

THE BASS CLARINET.

The B♭ bass clarinet shares the registral characteristics of the corresponding written ranges of the main B♭ clarinet, but sounding an octave lower. Its metal curved barrel and upturned metal bell gives it the appearance of a saxophone, but its sound, dynamic control, and expressive fluidity are quintessentially clarinettish. It maintains the remarkable colour of the clarinet's chalumeau register, but this colour sounds even more wonderfully rich an octave lower on the bass clarinet. Its clarion register is less bright and colourful than the clarinet's, giving it a rather neutral timbre. Still, its responsiveness to articulation and breath control are comparable to the clarinet. It is a distinctive solo instrument on par with the English horn.

Practically all bass clarinets made today have an E♭3 key. Most bass clarinets extend down to low written C's (sounding B♭2), allowing it to substitute for the cello and bassoon.

For score study it is important to know that some composers (mostly French) have used a convention known as the “German system” (go figure) for notating bass clarinet parts. In this system, notes written in bass clef sound down a M2nd. Today almost all composers use only treble clef in the part and transposed scores. In concert pitch score, of course, bass clef means what it always has, and may be used in alternation with treble clef, or even the treble clef with 8ve down, in whatever fashion makes the sounding pitches of the music easiest to read.

With a little practice, almost all clarinetists can play the bass clarinet adequately in its lower and middle registers, given a well-maintained instrument (not always an easy thing to find). It takes a dedicated specialist, however, to mine the really spectacular high range of the instrument with an altissimo all the way up to written G7 (sounding F6). In this best-case scenario, the bass clarinet has a low range matching the bassoon, while playing practically as high as the oboe.

THE EB CONTRA ALTO CLARINET.

In a perfect world, the B♭ Contrabass Clarinet would here be occupying our attention as a "common auxiliary" to the clarinet family. Its incredible sound and range (sounding down to C1 or B♭0) make it a viable alternative or complement to the contrabassoon, and one that can be played adequately by any respectable clarinetist. In reality, few bands (and almost no orchestras) seem to possess this instrument. The Contra Alto Clarinet is mentioned here as a fairly common member of concert bands, but not orchestras. Though not as agile as the bass clarinet, it is powerful and expressive in its low range. Notes written above the staff (sounding middle C and higher) will probably do more harm than good, except in those situations where harm is good.

CLARINET DOUBLING.

A large orchestra will have up to 4 clarinetists, assigned (from the conductor's right to left), clarinet 1, clarinet 2, E♭ clarinet, and bass clarinet. When there are 3 players, the 2nd player may be called upon to double B♭ and E♭, while the 3rd player doubles bass and B♭. The 1st clarinet almost never doubles. While one of the beauties of the clarinet family is how readily any clarinet player can play such an astounding array of instruments, it is true that a specialist, who owns and maintains an auxiliary instrument and practices it faithfully, will be able to offer much more to an ensemble than a less committed doubler.

Clarinet Family Orchestral Examples.

Here are examples from orchestral literature that demonstrate characteristics of the clarinet family.

CLARINET EXCERPTS.

Beethoven: Symphony No. 6 "Pastorale", I, 476-492. This example displays the bright, clear sound of the clarinet's clarion register (although it dips into throat tones in the 5th and 6th measures). It also demonstrates the instrument's agility and dynamic range, especially effective in the 4 measure diminuendo to pp.

Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 5, I, 21-37. This second phrase from the introduction to Tchaikovsky's 5th Symphony not only demonstrates the richness of the clarinet's chalumeau register, but also the broad, expressive dynamic range in the area. This "solo" is written a2; Tchaikovsky choose the sound of 2 clarinets in unison, giving the sound more roundness, warmth and depth.

Rimsky-Korsakov: Capriccio Espagnol, 11 measures after rehearsal letter K to section IV. Here the clarinet begins by imitating the solo violin, but takes the arpeggio figure further and faster, ending in virtual "sheets of sound."

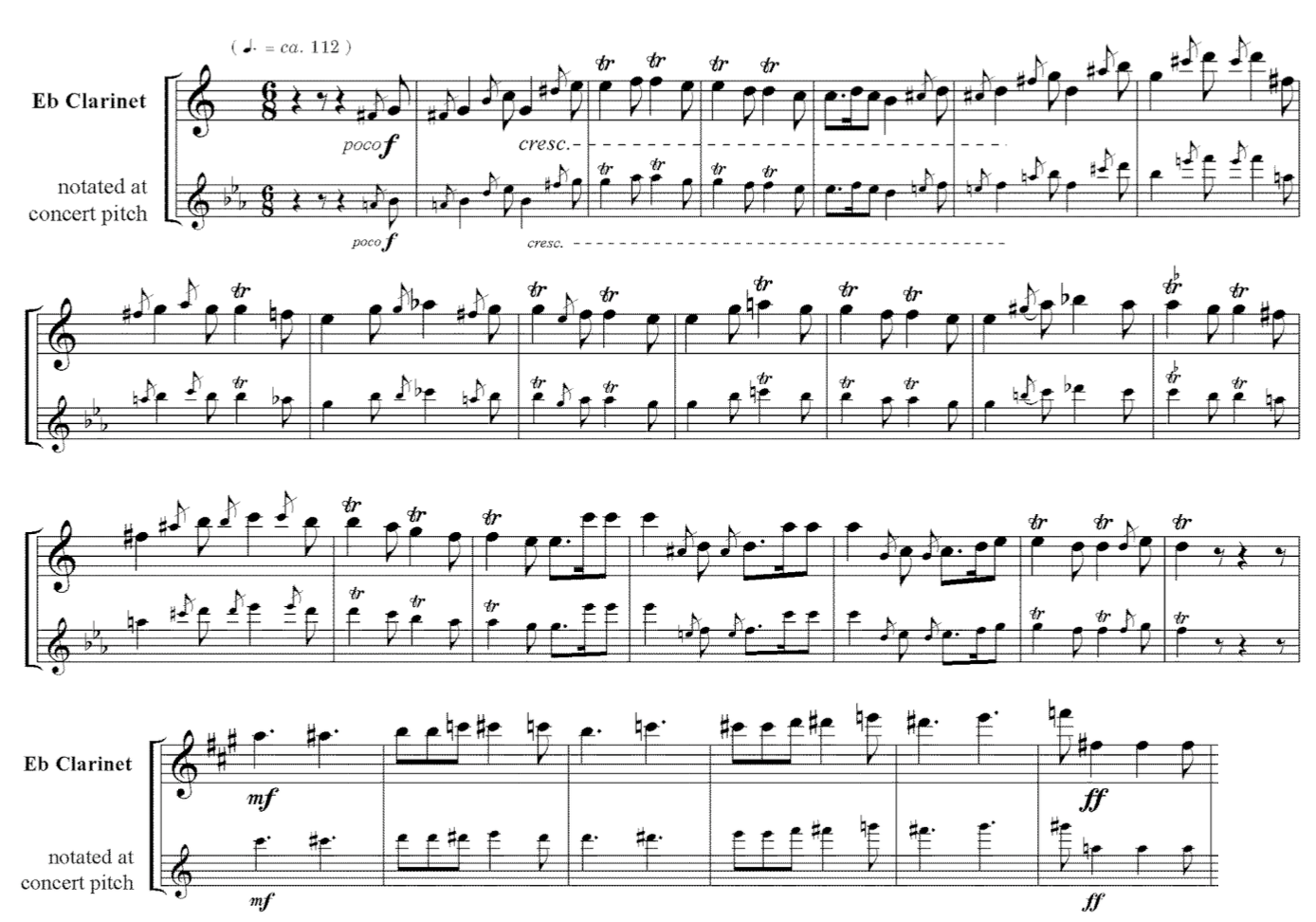

EB CLARINET EXCERPTS.

Berlioz: Symphonie Fantastique, V, m. 40-60, m. 390-395. This is one of the first appearances of the E♭ Clarinet in orchestral literature, and still remains the most famous. The surreal brightness of the high trills used to decorate this mocking version of Berlioz's idée fixe is almost a caricature of this instrument. The second passage shows the instrument ascending to a concert G♯6.

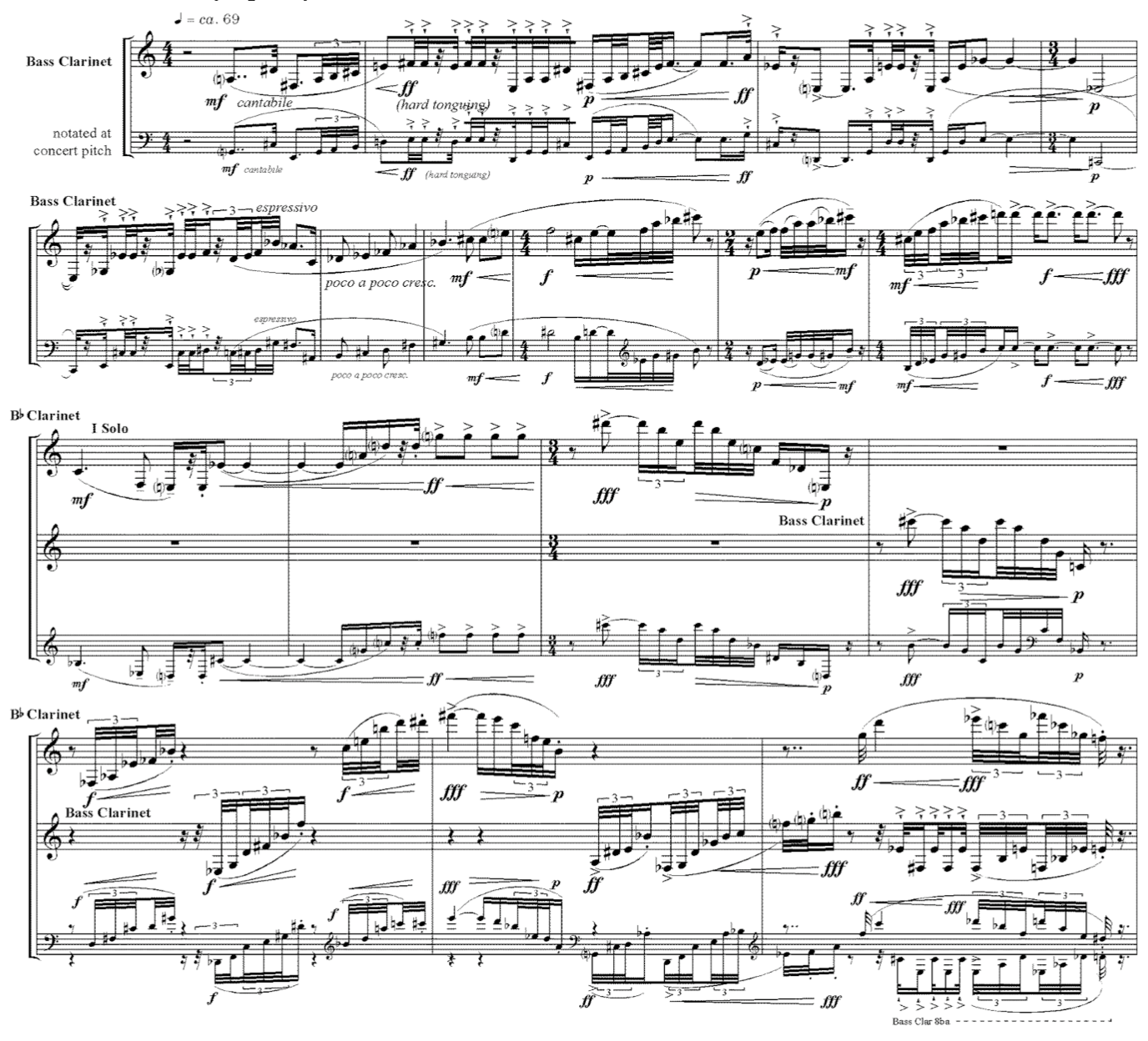

BASS CLARINET EXCERPTS.

William Schuman Symphony No. 7, 79-95. This solo (which becomes a duo with the B♭ Clarinet) is accompanied at first by strings and then by sharp muted brass chords; it displays the bass clarinet's exceptional range, agility and dramatic potential.