Woodwinds | The Flute Family

Woodwinds | The Flute Family

Extreme Orchestration

by Don Freund and David CutlerPublished: February 2024

THE FLUTE FAMILY.

The members of the flute family are the only wind instruments that do not use a reed or buzzing lips to initiate their sound. Air is directed from the lips free of a mouthpiece. The only resistance to the airflow is the player’s embouchure, allowing the tongue and mouth to be uniquely unencumbered. Because of this, the flute has a natural quality, freedom, and agility not found elsewhere in the orchestra. The term “flute” by itself refers only to the C-flute, the principal member of the family. Its upper auxiliary is the piccolo, the most common auxiliary instrument in the orchestra. The alto flute in G is much less common, but it is still considered a standard member of the large symphony orchestra.

THE FLUTE: A GUIDE TO THE REGISTERS.

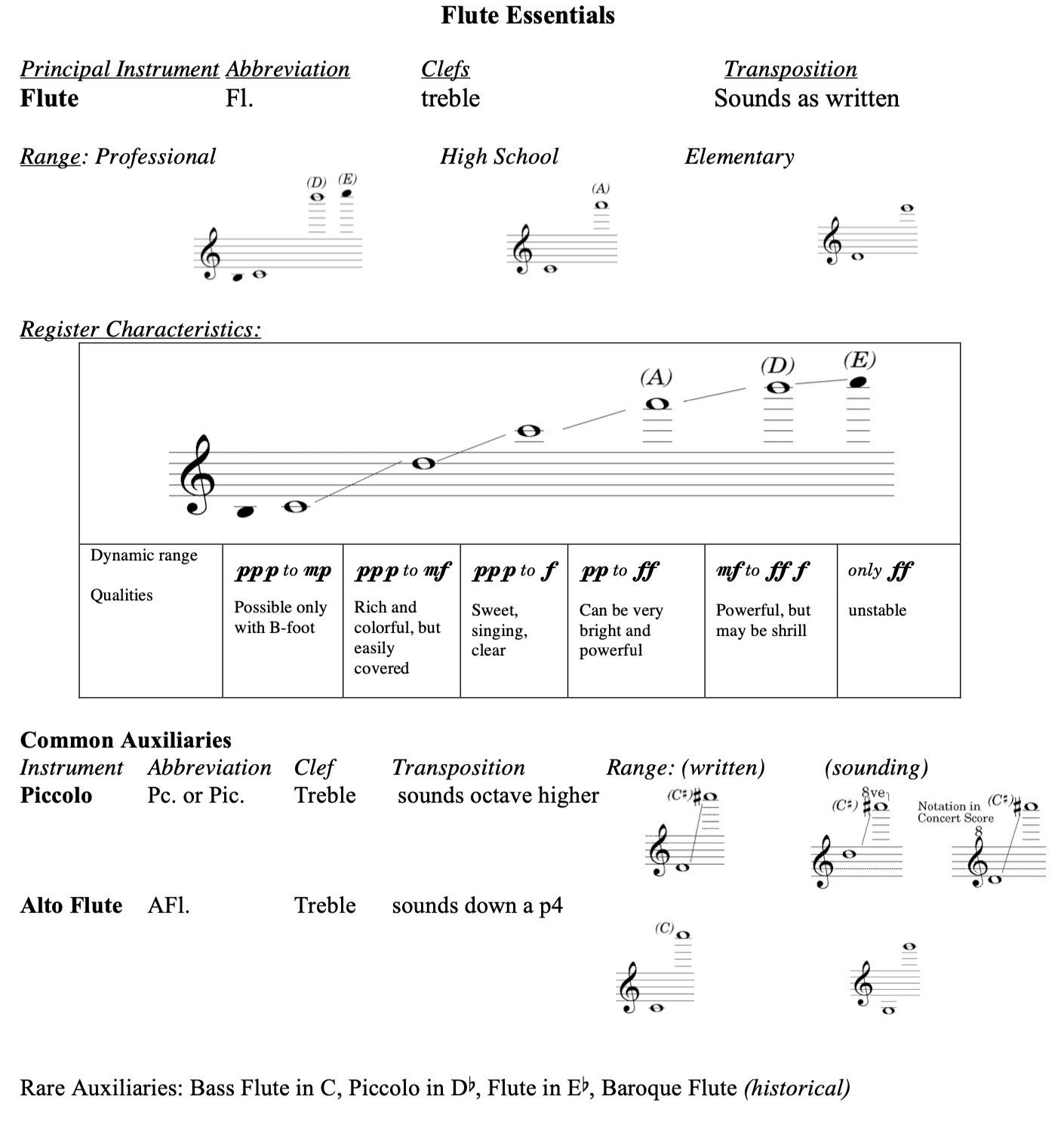

The flute’s volume is weaker in the lower half of its range; any note written in the staff or below will contribute little to a full orchestral tutti. Notes above the staff are clear, powerful, and expressive up to A6, becoming much more difficult to control as the range moves to C7 and beyond. Most American flutists at the advanced high-school level and beyond have instruments with the additional low B3 foot and open tone holes that allow for greater intonation flexibility (also useful for quarter-tone and glissando effects). The B-foot is less common in Europe, and some players prefer not to use it because it subtly alters the tone of the middle register.

The lowest octave is the register where the greatest degree of color variation is possible, but it is a register that can be easily covered by competing textures above a p dynamic level. The available dynamic range increases in the middle and top octave, where the flute can easily project extended lyrical solo lines. In this range, it also is the orchestra’s best all-purpose doubling color, adding substance and clarity to string passages doubled at the unison, or adding well-controlled brilliance when doubling an octave higher than brass. A flute can mix well with any other woodwind, adding strength and warmth, although somewhat neutralizing the color. In order for the flute to have its own recognizable color, it is better to leave it undoubled.

From A6 upward, it is very difficult to play the flute without some shrillness, which may be welcome in loud tuttis, but is better avoided in singing passages. D7 appears in many 20th-century scores, but should be used with an awareness of difficulty since fingering patterns, intonation, and especially dynamic control this high are extremely demanding. The high E7, when possible, is more dramatically stunning than lucidly musical. Generally, the 8ve mark is avoided in notating high flute music, because flutists are unusually adept at reading ledger lines. The practice of printing the actual note name in parentheses for pitches above A6 is particularly useful in flute parts.

FLUTE STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS.

When a passage demands velocity, adroitness, and virtuoso articulation, the flute is probably the leading candidate for the assignment. Fast scales and arpeggios, quick register shifts, trills, tremolos, and scintillating tonguing effects are practically second nature for professionals. Caution should be used in writing passagework from D#4 down. The little finger of the right hand must depress a different key for B3, C4, C#4, and D#4, so only trills or tremolos (or fast chromatic passages) that use alternation with D4 can be played quickly. Trills above G6 are awkward. Throughout the rest of the instrument trills and tremolos up to a perfect 4th create no problems.

Flutes require more air (and more breaths) than other wind instruments. Overlapping two flutes is a useful solution when an endless stream of music is desired, but designing or interpreting the material to include natural breaths is often more compelling.

Harmonics are more commonly found in flute parts than any other wind instrument. (See description and example in the introduction section.) Variations in the intensity of vibrato (including non-vibrato) are more effective for the flute than for any other wind instrument.

Instrument Studies for Eyes and Ears (ISFEE) | Piccolo

THE PICCOLO.

The piccolo is the quintessential auxiliary instrument. It is virtually a half-sized flute, sounding an octave higher, which mimics or even exaggerates all the flute’s characteristics. The piccolo’s most common function is to add a brilliant top to the orchestra. From its written G5 upward, the piccolo can easily be heard over the loudest tutti; from written A6 up, it can be painfully loud. (Remember, these top pitches are the highest notes on a piano keyboard.) The piccolo can match the flute in flexibility and virtuosity throughout its range. It often doubles the flute (or flutes) an octave higher—having flutes and piccolo play a sounding unison is an interesting compromise between the two sounds. The lowest octave and a half of the instrument has a woody, hollow sound, resembling the recorder or ethnic flutes, and providing a unique and seldom heard color resource to the wind section. Composers must devise extremely transparent textures to exploit the low register of the piccolo, which possesses even less penetrating power than the flute’s lower range. Care must be taken not to overuse the super-projection of the piccolo’s highest octave.

Extreme Caution!

The piccolo’s lowest written note is D4, not C4 as in the flute.

THE ALTO FLUTE.

The extension of the flute’s range downward a perfect fourth would be a dubious benefit if the results were simply a few extra weak, washed-out pitches. Miraculously, the alto flute’s added girth and length, sometimes accomplished by a U-shaped tubing, allows it to produce an even richer color than can be found in the flute’s lowest octave. Its principal contribution is as a solo instrument in its lower range; notes written above the staff have little distinctive color and are best assigned to the flute. Although pitches sounding from C4 to C5 are stronger than the flute’s, the characteristic color of the alto flute can easily be masked by surrounding textures louder than p. The alto flute is almost as agile as the flute throughout its range, though it requires significantly more breath.

Instrument Studies for Eyes and Ears (ISFEE) | Alto Flute

FLUTE "DOUBLING."

Almost all flute players have had experience playing the piccolo and alto flute and can be called upon to double. The switch between flute and alto flute causes few problems. Doubling flute and piccolo is more difficult, and is a skill that must be developed. Larger orchestras will have piccolo specialists.

Flute Family Orchestral Examples.

Here are examples from orchestral literature that demonstrate characteristics of the flute family.

FLUTE EXCERPTS.

Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 “Eroica,” 4th movement, m. 170-200 Although this passage (Ex.5.1) may look high, it is actually in the best tessitura for effective orchestral flute writing. In this range the flute can execute the fullest range of dynamics and articulation; its singing tone, crisp articulation, and facility with brilliant passagework can be easily projected over the orchestra when written above the staff.

Example 5.1: Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 “Eroica,” 4th movement, m. 170-200

[click for score and audio]

Brahms: Symphony No. 4, 4th movement, m. 89-105. This passage demonstrates the lyric colors of the flute in its high, middle, and low registers (Ex. 5.2). The staccato marks under the slur in the first three measures of this excerpt may be interpreted as indicating tongued legato rather than the half-staccato one would expect in a less Romantic style; the hairpin dynamics reinforce this legato quality. Since all of this passage is played only by the first flute, the marking “Solo” at measure 97 indicates how the music is to be, rather than who is playing. (This is a very useful marking, but it should preferably appear in italics under the staff, reserving “solo” above the staff for situations where it alternates with “tutti,” a situation found in band wind sections, but never in orchestra.) Brahms could also be accused of sloppy notation for not showing how long his “poco cresc.” lasts and how loud it gets, but one assumes the flutist will perform the last measures with a tone approaching forte so that these expressive low notes are clearly projected. Note that even though the quality of this passage is legato and expressive, the slurs are relatively short, projecting a rhythmic underpinning to the lyricism.

Debussy: Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune, m. 21-30 (rehearsal number 2-3). This excerpt shows the flute’s third statement of this famous melody, which began the piece as a four-bar unaccompanied solo. This statement is extended and appears over an accompaniment light enough to allow the color of the low flute to be fully appreciated; the accompaniment grows in richness as the flute ascends to C6. The combination of singing long tones with graceful arabesques displays the flute in its most idiomatically engaging character. Debussy did not indicate breaths, but even the best flutist will have to find a place to breathe every 2 or 3 measures at this tempo. Note the inclusion of the second flute, alternating with and then doubling the first flute, thickening the color as well as amplifying the projection of the line. The return to solo for the cadence is a remarkably effective touch.

Example 5.3 — Debussy: Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune, m. 21-30 (rehearsal number 2-3)

[click for score and audio]

These three short excerpts demonstrate the amazing agility, fluidity, and sparkling brilliance of the flute. All three passages are soft and delicate, but that does not prevent the composers from freely using a range of at least an octave above the staff along with the extreme low range. Note the use of single-tongued staccato in the Rossini and double-tongued legato in the Rimsky-Korsakov and Saint-Saëns excerpts. Also note Rimsky-Korsakov’s use of long and short slurs in his cadenza, and Rossini’s transient grace notes initiating his phrases. One flaw in the Rimsky-Korsakov: the double-tongue passage cannot possibly be played in one breath, but there is absolutely no place to hide a breath!

Rossini: William Tell Overture, m. 209-212 (rehearsal letter G)

Example 5.4 — Rossini: William Tell Overture, m. 209-212 (rehearsal letter G)

[click for score and audio]

Rimsky-Korsakov: Russian Easter Overture, rehearsal letter C

Example 5.5 — Rimsky-Korsakov: Russian Easter Overture, rehearsal letter C

[click for score and audio]

Saint-Saëns: Carnival of the Animals, No. 10, Volière (Aviary), m. 6-15 (rehearsal number 1).

Example 5.6 — Saint-Saëns: Carnival of the Animals, No. 10, Volière (Aviary), m. 6-15 (rehearsal number 1)

[click for score and audio]

PICCOLO EXCERPTS.

Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 4, 3rd Movement, m. 194-197. In this excerpt, the piccolo appears p over pp short brass chords, demonstrating extraordinary brightness and lightness in a very high sounding range. An earlier excerpt from this movement given at the end of this chapter shows the piccolo adding exceptional brilliance to the orchestration, playing in its high range and ff, doubling the flute which sounds an octave lower.

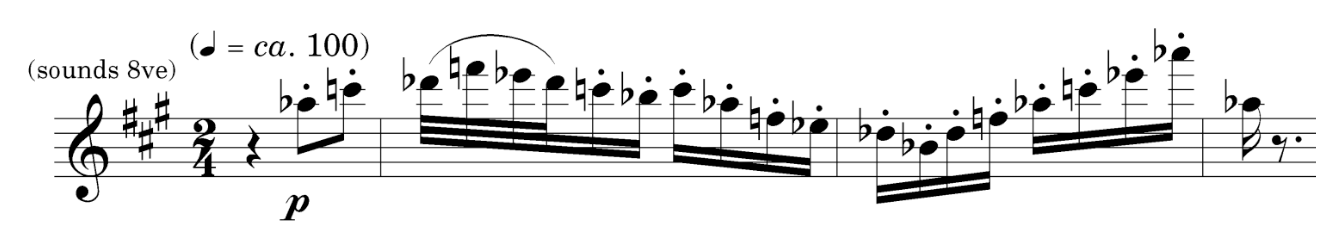

Stravinsky: Firebird Ballet Suite (1945 version), piccolo and flute, rehearsal number 16-19 (Piccolo sounds 8ve). At 16, the intertwined flute and piccolo dovetail with the clarinet; at 17 they provide a mutated doubling to the clarinets; at 18 they are “soloists” over quiet stings and harp. Note the various combinations of trills, staccato notes, slurred arpeggio sweeps, and triple-tongues staccatos. The tonguing pattern is spelled out at 18 (highly unusual), presumably to show a preference for the tokoto triple-tongue over the alternative totoko.

ALTO FLUTE EXCERPTS.

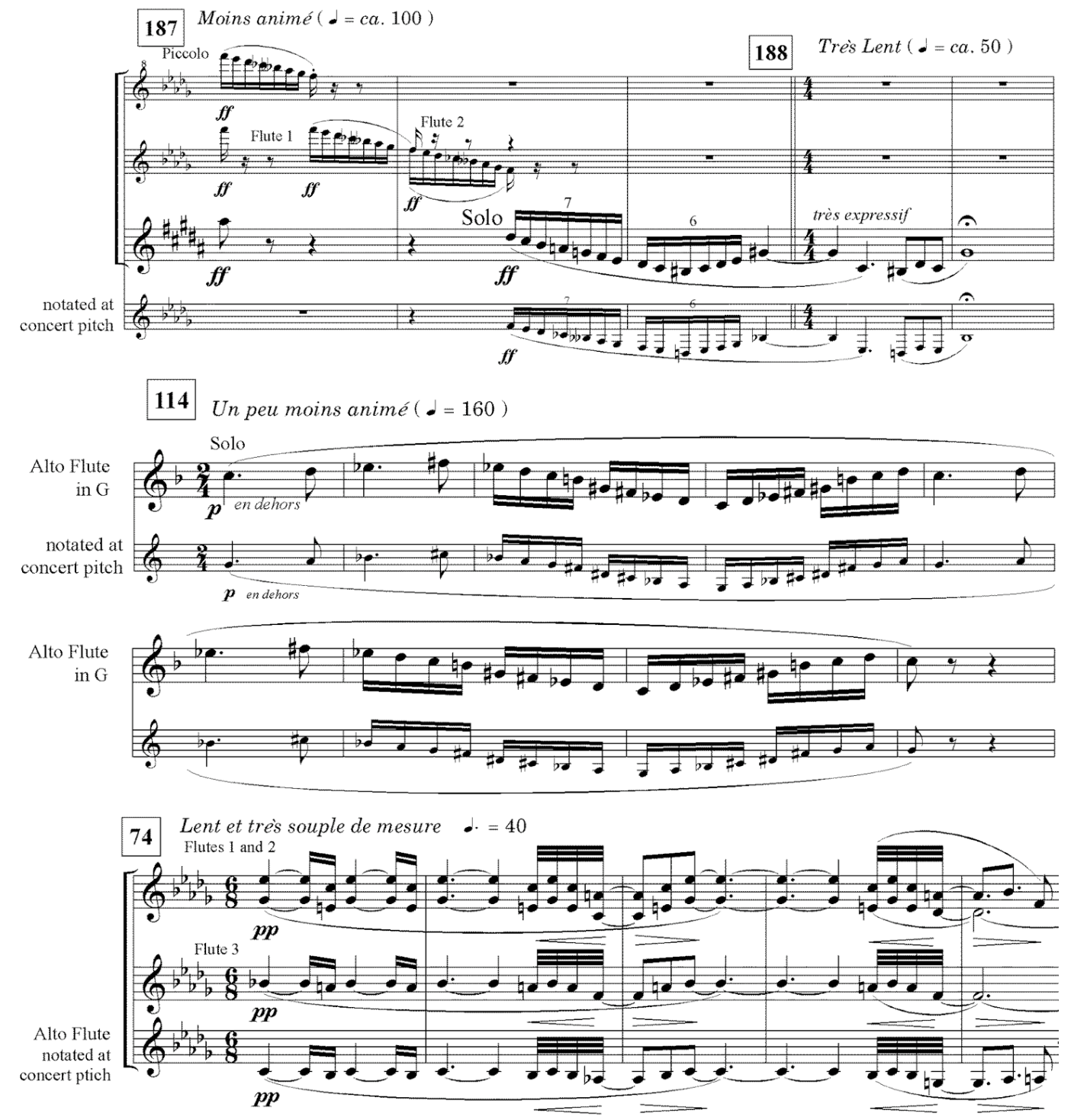

Ravel: Daphnis et Chloé, rehearsal number 187, rehearsal number 114, rehearsal number 74. These three excerpts from Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloé demonstrate various characters of the alto flute. The first example shows its fluidity and the marvelous color of sustained melody in its lowest range; in this passage the rest of the orchestra is silent until the fermata. The second example appears over a quiet but rather active accompaniment and shows the alto flute's ability to project a rhythmically profiled melodic idea in its middle and low range. Ravel marked this p en dehors (in the foreground). In reality, the performer has to play almost as loud as possible.