Woodwinds | Introduction

Woodwinds | Introduction

Extreme Orchestration

by Don Freund and David CutlerPublished: February 2024

Woodwinds are not usually called upon to evoke the sensuous beauty of strings, the heroic grandeur of brass, or the visceral power and splashy color of percussion. Their role in the orchestra is possibly the most subtle and personal of all the instrumental choirs. Developing an appreciation for the special qualities they contribute and discovering techniques for making the most of the timbral resources they provide may be the most important lessons an orchestrator can learn.

Woodwinds are far more varied in their sound and performance characteristics than the various members of the string or brass sections. Although the woodwind section can add some mass and brilliance to a tutti sound, it is more successfully used as a section of soloists, presenting distinct voices of remarkable character and contrast.

All of the woodwind families have auxiliary instruments, which not only extend the range possible in that family, but also contribute distinctive alternative timbres. “Doubling” on these instruments is commonly asked of woodwind players who are not the principal players of their section. Only the woodwind and percussion sections of the orchestra provide the composer with the opportunity to write for more instruments than there are players.

By simply applying two or three simple principles, one can readily grasp how all the pitches are produced on string or brass instruments. Woodwinds are far more complex; the manner in which tone holes are drilled into the instruments and the arrangement of the various keys and levers that open and close these holes are not at all linear. In the process of accommodating evenness of timbre, good intonation, and technical facility, woodwind fingering has developed into systems that are far more mechanical than intuitive. It is difficult for a non-woodwind player to conceptualize how a passage might need to be fingered on a woodwind instrument without consulting a fingering chart.

Fingering systems for woodwind instruments generally evolved around the concept of “overblowing.” Once a chromatic fingering is in place for the fundamental octave of the instrument, notes in the higher registers of the instrument can be played by forcing the sound wave to divide into a half, a third, or even a smaller segment of its length, similar to the way harmonics operate on string instruments. This division of the sound wave is evoked by a combination of the player’s breath and embouchure called “overblowing,” frequently used in conjunction with a register key. The set of pitches produced by one particular partial represents a “register.” Registers become smaller and less definitive as the partials get higher and closer together. A complex of acoustic and ergonomic factors keep this fingering system far from being consistent and predictable.

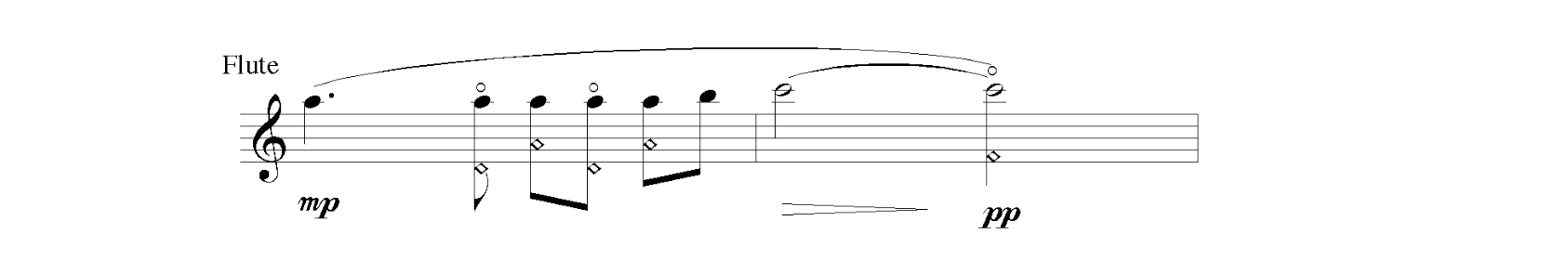

In the woodwind world, the term “harmonic” refers to a note whose color is slightly altered by the use of a non-standard fingering, that is, overblowing to partials other than the ones normally used. The clearest example of how woodwind harmonics operate may be seen in the flute. Since the second octave of the flute’s range is produced by overblowing the fingered notes of the bottom octave to produce the 2nd partials of these fundamentals, notes played in this fashion produce the normal flute sound and are not considered harmonics. The notes from G5 upward can be played by overblowing to produce the 3rd partial, a perfect 12th above the fingered fundamental; that is, the second partials are standard fingering, while the 3rd partials are “harmonics.” The timbral difference between a pitch produced by the standard fingering 2nd partial and the “harmonic” fingering 3rd partial is a subtle one, and woodwind harmonics are most effective when they are heard in close relationship to a standard fingering note, as in the example given below. Although “harmonic” in the strictest sense refers only to the use of non-standard partials, a similar effect can be invoked on wind instruments by the use of any “false fingering” which results in a paler, less stable tone. Usually composers will simply indicate a harmonic effect with a circle over the note, allowing the player to choose the means of producing the “harmonic” sound.

The pitches with circles above them are played as harmonics. The diamond shaped noteheads indicate the fingering. The harmonics in this passage all use the third partial harmonic, sounding a perfect 12th above the fingered note. The fingering indicated for the 3rd and 5th notes uses the second partial (the standard flute fingering), overblowing at the octave — the same fingering used for the first note. It is possible to slur this passage, and allow the color changes to create the articulation.

The note-by-note, non-linear aspect of woodwind fingering limits nuances such as tone bending and glissandos to what can be accomplished with the embouchure (tone-bending is limited to about a half-step downward from the fingered note), or what can be faked (generally performers are left to their own devices to execute glissandos, using some combination of scale fingerings, partially opening the instrument’s open holes, and embouchure shifting). Upward glissandos are easier to fake than downward ones, but even such a familiar glissando as the one found at the beginning of Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue is not something every clarinetist can be expected to have mastered.

A welcome by-product of the complexity of woodwind instrument key systems is the existence of a seemingly infinite combination of fingerings, some of which serendipitously create unusually colored pitches, microtones, or even collections of pitches called “multiphonics.”