Partial

EN | FR

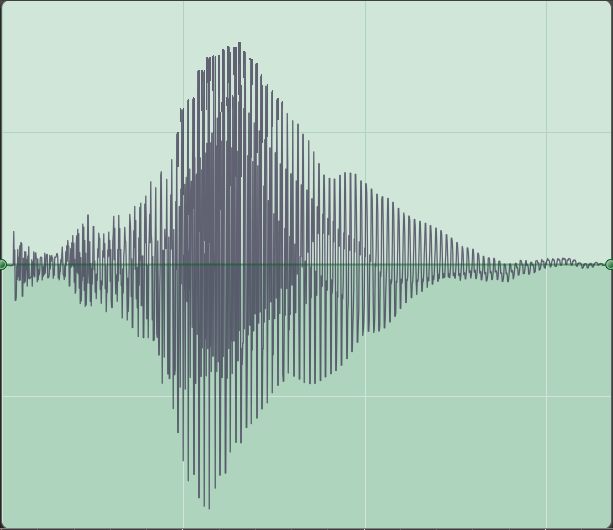

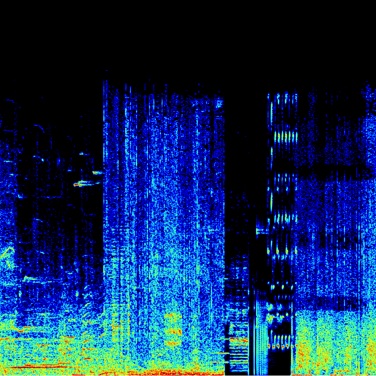

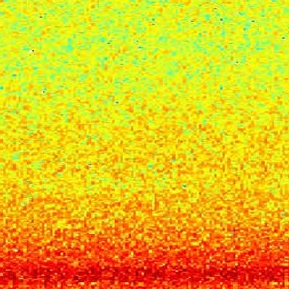

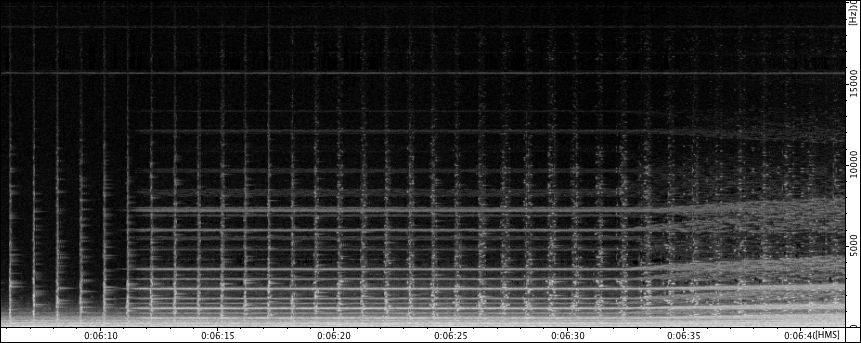

Although we may perceive sounds such as musical notes as singular, self-contained units, the physical reality often suggests something very different. Most sounds we hear are actually complex mixtures of many different sound components, some of which are noisy and transient, others of which may have stable frequencies. Our auditory system groups these elements together amazingly well, so that we are usually not aware of the component parts of the sound but only of the sound as a whole.

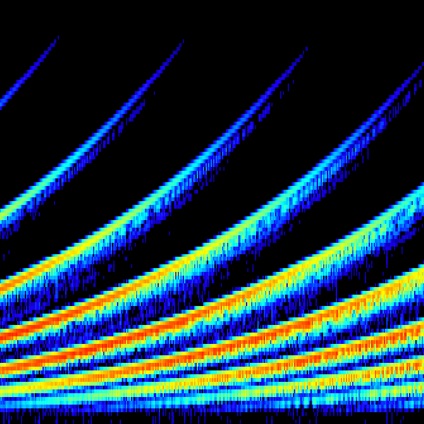

Sound components with stable frequencies, which are represented mathematically as sine waves, are called partials. The number and relationships between partials have powerful effects on the way we perceive the sound. If all of the partials are related by simple ratios (n, 2n, 3n, etc), they are called harmonics and fuse together almost perfectly in perception (as suggested by the principle of harmonicity in the Auditory Scene Analysis). The result is a harmonic sound with a clear, unambiguous pitch, such as the human voice and most musical instruments. In a harmonic sound, the lowest partial, which usually corresponds with the sound’s perceived pitch, is called the fundamental, while upper partials are called overtones. If, on the other hand, some or all of the partials are related by more complex ratios, the result is a more diffuse sound that is more like a chord than a single pitch. Such sounds are inharmonic: familiar examples include church bells, metal bowls, and clanging glassware (cheers!).

Excerpt of spectrogram of Barry Truax’s Riverrun (1986). The horizontal lines correspond to partials.