Orchestrating Timbre

Orchestrating Timbre

Unfolding Processes of Timbre and Memory in Improvisational Piano Performance

by Magda Mayas

Originally published in 2019, University of Gothenburg

Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Fine Arts in Musical Performance and Interpretation

Excerpts reprinted with permission by the Timbre and Orchestration Writings on March 31, 2023

Published by Göteborgs universitet (Avhandlingar).

This doctoral dissertation is No 76 in the series ArtMonitor

Doctoral Dissertations and Licentiate Theses, at the Faculty of Fine, Applied and Performing Arts, University of Gothenburg. www.konst.gu.se/artmonitor

The dissertation Orchestrating Timbre—Unfolding Processes of Timbre and Memory in Improvisational Piano Performance contains a book and a Re- search Catalogue Exposition available at URL: http://hdl.handle.net/2077/62283

The Research Catalogue exposition is also available at URL: https://www.researchcatalogue.net/view/382024/382025

Graphic design and layout: Fredrik Arsæus Nauckhoff

Cover photo: Magda Mayas English proofreading: Helen Runting

Printed by: BrandFactory, Kållered, 2019 ISBN: 978-91-7833-722-4 (printed version) 978-91-7833-723-1 (digital edition)

© Magda Mayas, 2019

Keywords: extended timbre, improvisation, composition, inside piano, prepared piano, listening, timbral memory, spatialization, gesture, choreography, musical perception, embodied musical performance, artistic research.

Thesis Abstract

This doctoral thesis presents how the orchestration of timbre is investigated from a performer’s perspective as means to “unfold” improvisational processes. It is grounded in my practice as a pianist in the realm of improvised music, in which I often use preparations and objects as extensions of the instrument.

As practice-based research, I explore multiple, combined, artistic, and analytical approaches to timbre, anchored in four of my own works. The process has also involved dialogues and experimental collaborations with other performers, engineers, an instrument builder and a choreographer. It opposes the notion of generalizable, reproducible, and transferrable techniques and instead offers detailed approaches to technique and material, describing object timbre, action timbre, and gesture timbre as active agents in sound-making processes.

Whilst timbre is often understood as a purely sonic perceptual phenomenon, this view does not accord with contemporary site-specific improvisational practice; hence, the need to explore and renew the potentiality of timbre. I introduce and argue for an extended understanding of timbre in relation to material, space, and body that embraces timbre’s complexity and potential to contribute to an ethical engagement with the situated context. I understand material, spatial, and embodied relations to be non-hierarchical, inseparable, and in constant flux, requiring continuous re-configuration without being reduced or simplified. From a performer’s perspective, I define “orchestrating” timbre as the attentive re-organization of these active agents and the creation of musical structures on micro and macro levels through the sculpting and transitioning of timbre—spatially, temporally, physically, and mentally—within a variety of compositional frameworks.

This requires recognizing the multiple and complex roles that memory plays in contemporary improvisational practice. I therefore introduce the term timbral memory as a strategic structural, reflective, and performative tool in the creation of performing and listening modes, as integrated parts of timbre orchestration.

Reaching beyond the sonic, my research contributes to the field of critical improvisation studies. It addresses practitioners and audiences in music and sound art, attempting to also constitute a bridge from artistic research in music—often viewed as a self-contained discipline—into multiple artistic fields, to inspire discussions, creation and education.

Chapter Summaries

Chapter 3: Objects

This chapter focuses on objects and preparations used as instrumental approaches and material agents in music making. “Object Memories” constitutes a series of short reflections that are told from the author’s recollection and describe the role that objects play in the mental and physical structuring of sound material in the author’s artistic practice. These are followed by “Object Stories,” a collection of short stories by different artists and musicians, reflecting the manifold and unique ways that technique and vocabulary in music making are developed through objects. The stories oppose a compartmentalization into labels such as “extended techniques,” showing a multiplicity of performance practices within improvised music.

Chapter 4: Performative Timbre

This chapter describes an intensive listening study, “Performative Timbre,” undertaken in collaboration with Palle Dahlstedt. The author uses a subjective similarity measurement as an adaptation of the scientific timbre space method, articulating timbre in relation to material, gesture, and playing method, through an extensive listening and comparing process. This is followed by an introduction to strategies of mapping, as a mental structuring of vocabulary and technique, articulating connections and relationships between active agents in timbre orchestration.

Chapter 5: Catalogue of Shapes and Motion

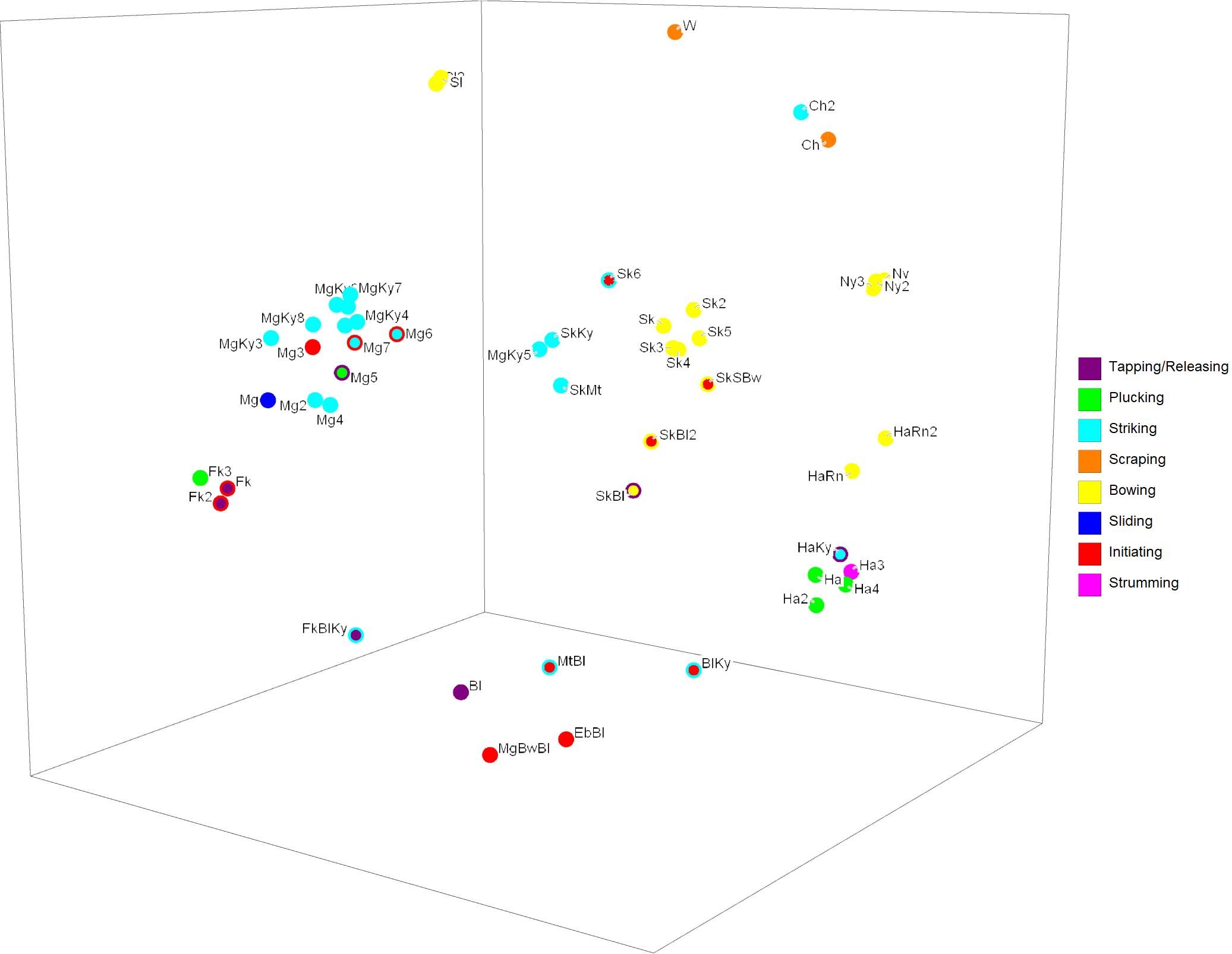

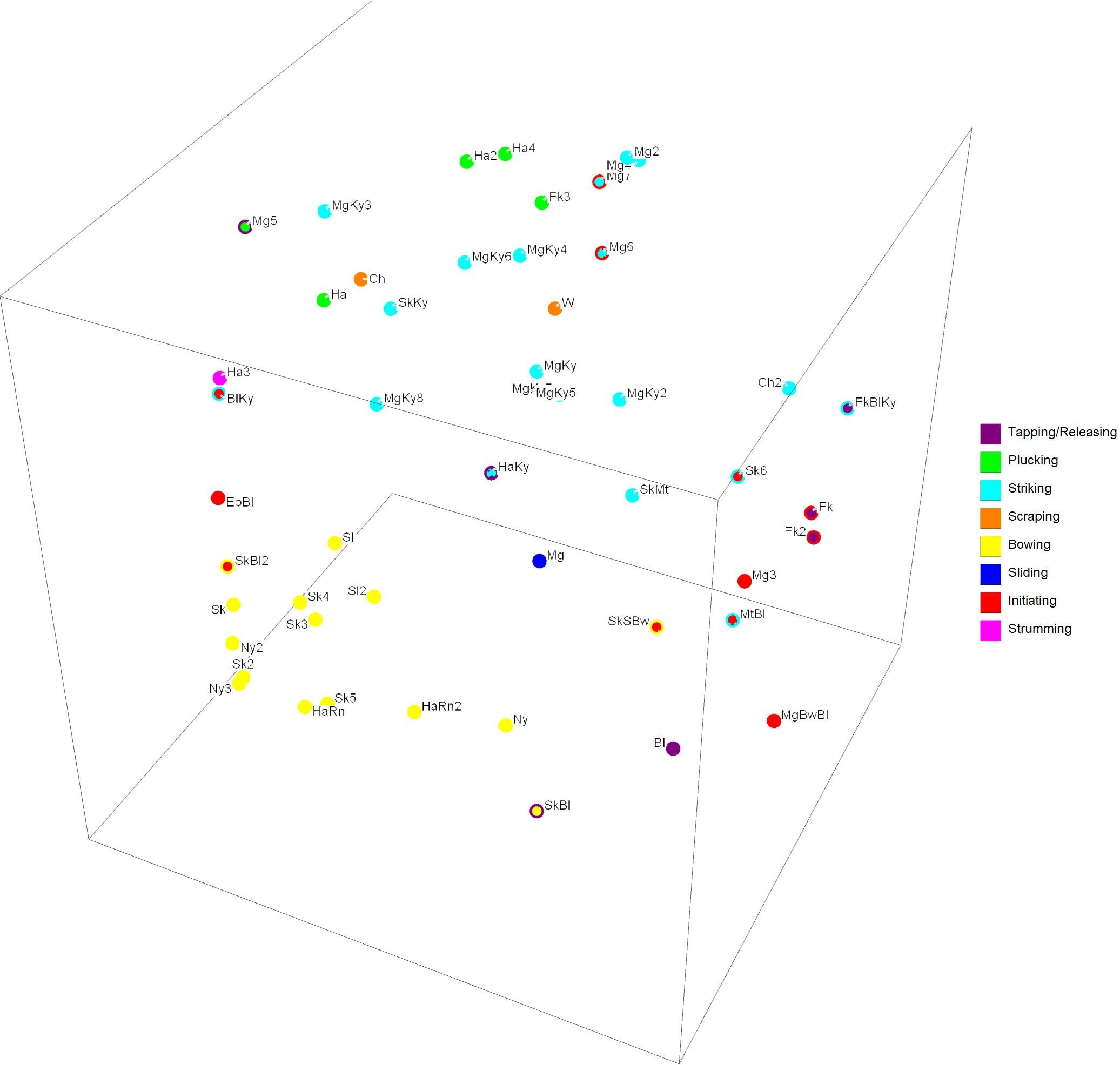

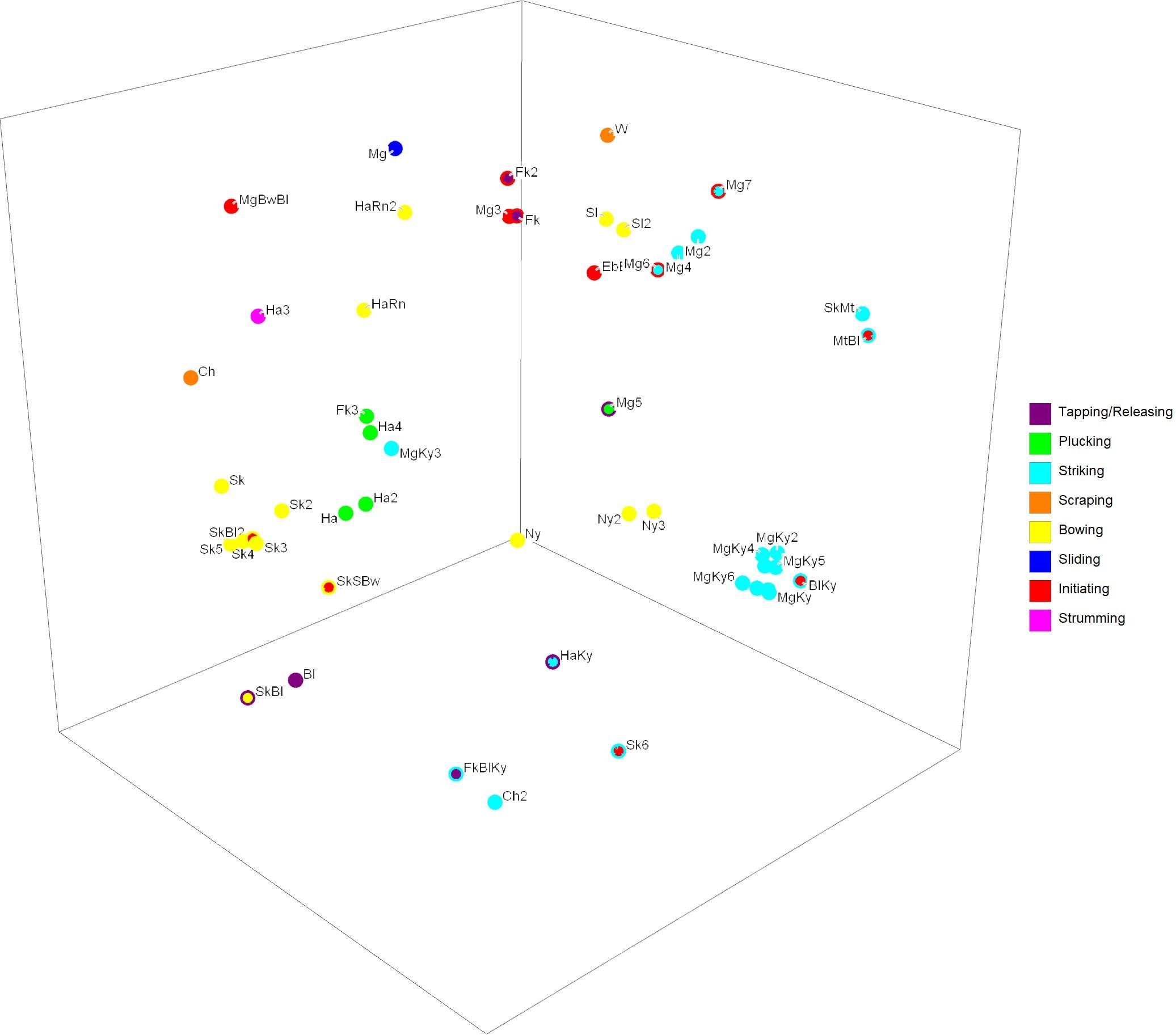

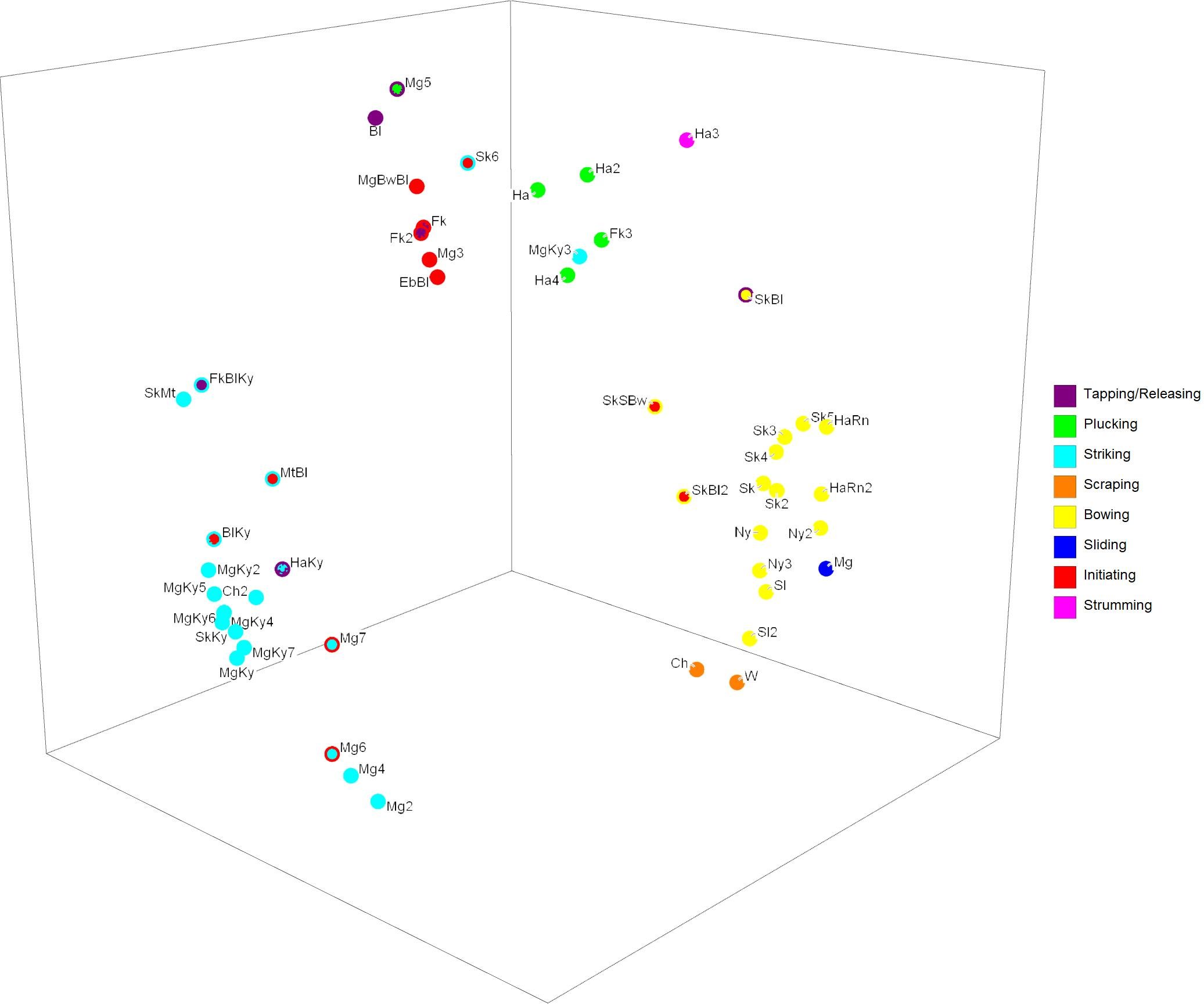

This chapter translates the outcomes of the listening comparisons and ratings from the “Performative Timbre” study into graphical representations that were developed together with Palle Dahlstedt. Multi-dimensional scaling (MDS), a spatial analysis method, is used to visualize the collected data, resulting in four perceptual timbre maps: the Object Timbre Map, Action Timbre Map, Gesture Timbre Map, and the concluding Sonic Timbre Map. These maps are analyzed and compared to each other, revealing relationships in between and within the different performance aspects and unfolding details and complexities as part of timbre orchestration in improvised music.

Chapter 3:

Objects

How do objects shape my ideas and how do I shape musical structures through objects? My idiosyncratic collection of objects inside the piano, and the way they are laid out and placed, is a composition in itself, setting a scene of possibilities. The objects expand the piano, becoming both instruments in themselves and part of the piano, transforming and adapting it to the situation and to what is required in the moment. Together with the piano they are also extensions of my movements and body, facilitating and manifesting my musical ideas. As such, they play a major part in my decision making in improvisational processes and timbre orchestration, while I am performing.

Continuing the narrative developed in my earlier comments on the instrument-performer relationship, as well as in relation to technique and vocabulary as multi-sensory approaches, in the coming chapter I will focus on questions of materiality in my performance, and on the objects and preparations that I use inside the instrument as material agents in music making.

Bruno Latour puts forward Actor Network Theory as a way of speaking about material semiotic relations and the agency of “human and nonhuman actors,” which are both understood to take part in the same story and social network (Latour 2005). In embedding an imaginative process, objects carry meaning; in my practice, that meaning is revealed in the relationship that I develop with them. The interaction with objects and instruments helps me understand sound-producing processes and (musical) gestures on a sensorial level. Rather than being tools to fulfill a purpose I assign to them, objects stimulate an artistic imaginative process and prompt ideas that I was not aware of prior to engaging with them.

Erin Manning calls this relational quality and capacity “object-events”: “We perceive with objects, catching the edges of their contours, participating in the relations they call forth... This quality of relation is what gives an object-event its potential infinitude” (Manning 2009, 81). The detailed and intimate relationships that I maintain with objects in my practice triggers infinite artistic possibilities and inifinite expressions of artistic agency. The physicality of each object allows for and limits the actions that can be performed with it, and likewise objects seem to “find” movements and resulting structures. The specific shape, weight, and materiality of each object invites and triggers actions, gestures, and sounds, thereby suggesting ideas and structures within a musical composition.

In chapter 2, I address the way in which musical ideas are shaped and originate from the instruments they are performed with. The same might be said of objects more generally, and the systems which they compose. Jean Baudrillard, writing in A System of Objects, points out that “objects do not merely help us to master the world by virtue of their integration into instrumental series, they also help us by virtue of their integration into mental series, to master time...” (Baudrillard 1996, 94, emphasis original). Technique and vocabulary, as I have argued in chapter 2 of the thesis, imply a need for a system, an internalized knowledge, or an idiosyncratic logic and mental structuring of the actual physical material at hand. Detailed attention must be paid to how one uses and develops sound material and timbre if one is to be able to control and apply timbre in an improvisational context (see also my discussion of mind maps at chapter 3.2). In my performances, I instrumentalize and individualize objects, and in so doing I set temporal, spatial, and timbral parameters, which initiate a dynamic feedback loop of action and reaction. Sherry Turkle states that “objects bring theory down to earth”, building a connection between the physical and abstract, thought and feeling and function as tools to think and create with (Turkle 2007, 8-9). “Physical objects engender intimacy,” she explains, through the sensual relationships that we develop with them (ibid., 323). This intimacy is part of and a precondition for an idiosyncratic approach to technique. Thinking and creating through objects is something that I constantly do within my practice, as is illustrated in the constantly changing collection and setup of the instruments that I use. The objects contained in my current work setup are:

Fishing line and nylon thread of different brands, colors, and thicknesses

A guitar plectrum [no picture]

Setting up the objects inside the piano is quite ritualistic, even though objects and placement change constantly—sometimes, I try out and engage with new things, and some things I leave untouched for months. Putting rosin powder on my fingers feels like wearing a work uniform, a literally embodied part of performing. Some objects have been part of my work setup since the very beginning, others might only be used for short periods. The collection keeps changing and expanding. Certain objects are placed regularly on the same spots—for example, the metal balls that resonate on the hitch pins behind the bridge—and yet, sometimes this is not possible, and due to different layouts of the instruments, the ball might not always remain in that position and move and roll of its spot too easily. Sometimes I set up a fork, a magnet, or fishing line in unusual positions, in order to force a surprise. I have spent time with each object, getting to know its physicality, how it feels in my hand, what I can do with it and what it makes me do.

Instruments, I argue, facilitate and limit our musical thinking. My musical vocabulary, the way I structure and think about a musical narrative, and the choices that I make when I improvise, are all contained in and are possible through the objects that I use, the piano being one of them. Getting to the core of how I think and act musically means engaging with the relationships that I develop with these objects through the tactile, haptic, and aesthetic experiences that they provide and the sensory response that I receive from them.

As the instruments differ largely from place to place, pianists are confronted with constant unfamiliarity, which can be both fatiguing and exciting. Objects tie a connection between the piano and me, they offer a sense of safety and trust. Susan Stewart speaks of “... this capacity of objects to serve as traces of authentic experience ...” (Stewart 1993, 135), and I can sense these traces in the objects when I perform, as experiences of past performances lived with and through them.

Collections of short autobiographical stories and memoires such as Evocative Objects by Sherry Turkle (2007), Sophie Calle’s True Stories ([1994] 2017), or Walter Benjamin’s “A Childhood in Berlin” ([1932-1938] 2010) often have objects at their core, as material agents which facilitate, signify, and connect events and relationships. Placing objects within a narrative is an act that comes very close to the ways in which I think about and work with material in my practice; as such, I test this strategy through three stories (below). Whilst I was both writing these stories and reading stories from other musicians (see “Object Stories”), I noticed how the work process is often closely connected to a sense of community and an ongoing exchange of ideas by way of meeting and playing with other people. Communicating, spending time with each instrument, discovery, and idea, alone and with others, adds layers of time and experiences, of trying and failing, and memories which give that work value and context. For me, these stories are also a way to connect loose ends, starting at the beginning of my experiments inside the piano and how that experience ties in with my decision-making process when I perform today. In writing the stories, I picked three objects which are very dear to me. These represent different periods in my musical life, and each object facilitated the development of a very different musical approach. I begin with the stone ball, which is perhaps the oldest object that is still in my collection; I then turn my attention to the magnets, which I first heard about through pianist Cor Fuhler in 2001, but only started experimenting with many years later; and finally, I finish by addressing the fishing line that I have employed in my practice as a result of a collaboration with composer Phil Niblock.

A Pale Green, Stone Ball

Heavy, about 5 cm in radius, it is used and old and I have owned it for about twenty years. In a performance with a dancer, at a house concert in my living room, she moved around the piano and unexpectedly took this ball and placed it on the hitch pins at the bridge, where the strings are connected to the soundboard. And suddenly the sound changed when I pressed down the keys, like the soft hiss of an old shellac record or a distorted guitar. I was amazed. Later on, I learned that other pianists use similar techniques and objects and whilst these are self-invented in each case, they are also shared. From then on, I used this “effect” as a technique in my playing. I collected more balls—different sizes, of stone and metal—and experimented with them. This object enables and transforms so many sounds; gently rolling it over the strings with my hand makes the softest glissandi, moving around between pitches: a very fragile sound. I use it in combination with other techniques and objects, for example, I bow a string with one hand and roll the ball over that string with the other, making a sound resembling a pigmy flute. I still come up with new ways of using it and somehow holding this stone ball in my hand while I perform makes me feel safe. There is actual trust, as if there were memories embodied in this object, as if we had been through many experiences together, which we have.

Magnets

Dutch pianist Cornelius Fuhler, who is based in Australia, told me about using magnets on piano strings when I took a lesson with him in 2001, when I just started out to reach inside the instrument. He mentioned strong magnets made of neodymium with a strength to lift many kilos and which, attached to the piano strings, bring out different harmonics, when playing the respective notes on the keyboard. There is often a time delay between the initiation of an idea and the right moment in time to engage with it, and it was only many years later that I became interested in experimenting with magnets myself. I started using magnets of all kinds of shapes, strengths, and sizes, in a variety of ways, often to initiate sounds, sometimes by setting column-shaped magnets into motion which vibrate on the strings, or other times by moving a small round magnet across the string in an interrupted glissando. As preparations on the strings, they afford huge flexibility in comparison to similar sounds of the Cageian prepared piano repertoire, producing everything from gamelan to toy-piano-sounding timbres, and they can be removed in an instance and still create endless microtonal nuances. I love the aleatoric element they entail, when throwing small, cube-shaped magnets on the strings, which land in unpredictable positions, adding a visual and theatrical touch to the performance. Some magnets can break off little splinters when hitting together too suddenly, which then changes their shape and makes them sit or vibrate on the string in a new position, bringing out yet another timbre. Recently, I started amplifying magnets placed on the strings with a guitar pickup, revealing deep drone-like durational sounds, unveiling and honing in on new layers of magnetic vibrations.

Fishing Line

One of the advantages of playing inside the piano is undoubtedly the way in which it is possible to produce sustained sounds (which can be achieved by, for instance, bowing the strings). I first started using fishing line on the strings of the piano for a project with composer Phil Niblock, where he asked me to bow the lower register strings in a sustained way on various pitches, which he then superimposed, filmed with small hand cameras attached to my wrists and turned into the audiovisual installation work N+M (work by Niblock 2010). I had not used nylon strings or bow hair prior to that, as I thought of my way of playing as more pointillistic—I was more interested in fast-changing structures than sustained pitches or drones. This experience certainly opened something up for me, not only in the obvious sonic plane of adding long sustained notes to my vocabulary, but in introducing a different temporal feel and pace to my work. I remember the process of recording each pitch for around 15-20 minutes and trying to be as consistent and steady as possible, and the very satisfying, calm feeling that gave me: despite the big arm movements necessary to produce the bowing sound, I felt like I could keep going for hours, getting into an almost meditative working pace or rhythm, immersed by the changing timbral details, changing harmonics, and the tempo of the pitch that I was bowing.

I expanded the use of fishing line in my practice by tying it to one or multiple strings, which I can perform with one hand or by seamlessly changing hands; and by weaving fishing line under one or multiple strings bowed with both arms, changing the position of the fishing line on the string to allow for more variety and bring out different harmonics.

In 2018, I decided to ask musicians, colleagues, and friends who used objects additionally to or as instruments in their practice to contribute in generating a small collection of short stories. The result, “Object Stories,” is not a general survey or study, rather it came about because I was interested in their idiosyncratic relationship with and approach to music making through these objects. The stories here are all written by the respective musicians indicated in the heading, although I reproduce them in partly shortened and edited form here. I asked each musician if they could share a short text, story, or anecdote about a single object (of their choice) which they use in their practice. I asked them to write about how they came to use this object, what it means or represents to them, what it enables them to do, and how it makes them feel, and whether there was anything else they would like to share about the object in the context of an object-performer experience.

There is an incredible diversity of approaches in these 16 stories, which reflect the manifold and unique ways technique and vocabulary in music making are developed through objects. The authors talk about what objects can evoke and afford, and they describe the situated knowledge which is developed and gained from dedicating time to objects as (additional) instruments. Rather than short representations of techniques, these “real-life” stories reveal the reasons and intentions behind the diverse ways in which musicians relate to instruments. The stories challenge a compartmentalization into labels such as “extended techniques” (something that I likewise oppose in chapters 1 and 2 of the thesis) and instead celebrate the uniqueness of creating. An object, a movement, a sound, or a technique always has to mean something to the performer and listener, these stories suggest, if it is to be of value.

Often the transformation or transitioning process of the object itself is at the core of the stories, which tend to describe moments where the object demands that the performer adapts and changes their approach and in turn develops new ways of using the object, sometimes over many decades or over the course of half a century, as in Gino Robair’s story of a bicycle horn that becomes so completely detached from its original function that it has to be continuously reinvented. In turn, the objects also ask for a transformation of the instruments they are applied to, as well as a transformation of the performers’ approach to those instruments, which is at times so serious that it seems to invent an entirely new instrument.

There is an expression of incredible joy in finding and “foraging” for objects, in natural or urban environments, as in Dave Brown’s encounter with the streetsweeper blades, Benoit Delbecq’s continuously changing and growing collection of wood sticks, or Johannes Bergmark and Rosalind Hall’s “meetings” with objects in secondhand stores and flea markets. Here, the element of finding or “stumbling upon” a new object or playing technique is essential and seems to resonate with the entire performance attitude—of improvising with the environment, and with what is at hand and what is presented by a particular circumstance. Marta Zapparoli speaks of the need for imperfection, unpredictability, and risk that is involved in her instrument setup, which is provided by the instrument-objects; while James Welburn’s story of the innocent pipe describes it as a “wildcard” which invites “accidents” into the music and offers ways of “unlearning” or reinventing.

The objects that are addressed in the stories are mostly entirely unique; they are repurposed and made to function in addition to other instruments and in turn the objects change them. Sometimes, object-instruments are gradually destroyed: they disintegrate through extended use and travel, as in Steve Heather’s story of a metal camping plate; or they simply wear off; or they are returned to their place of origin, as in Burkhard Bein’s story of the stones that are found only on one particular beach in England.

Objects can at times be embodied by the performer—literally, as is the case of Ute Wassermann’s palate whistle, which she places in her mouth behind her teeth. Sometimes, objects form such a crucial part of the instrument-performer relationship that playing the instrument without them becomes nearly unimaginable, as in Rosalind Hall’s story about the loss of the echo mic, or Clayton Thomas’ loss of a metal bar. Instrument builder and performer Johannes Bergmark goes so far as to describe the relation between his sound objects, which mostly work in combination with each other’s sonic properties, as that of a “large family gathering,” which speaks of a unique and refined performer-instrument relationship.

All of the “Object Stories” describe the sounds produced through these object-instruments and invented techniques as detailed, unique, rich in timbre, and multi-sensory: the touch and texture of the material, how it relates to the performer’s body or gestures, its diverse use and flexibility seems to be essential and shows a multiplicity of performance practices within improvised music. The process of finding/ choosing the adequate objects is a complex one—it happens by way of chance, discovery, searching, making, systematic improvement— and it is often related to specific playing conditions. The most important and exciting part seems to lie in the development of a musical language that is appropriate to this object and combining it with the other object-instruments in one’s collection and thereby activating its potential. Bringing it to life, so to speak. In my own practice, this is often a process which happens over many years and leads to personal relationships with and compositional approaches through objects I perhaps would not have discovered in any other way. The development of such relations is crucial to understanding technique and vocabulary as idiosyncratic, multi-sensory and continuously re-invented (see chapters 1 and 2).

As part of investigating and mapping my technique and vocabulary, and also as a preparation for the project described in chapters 4 and 5, I made a structured inventory list of material I found to be representative of my vocabulary. This list was developed into two conceptual mind maps which represent connections between sounds and reflect upon:

The material/objects used to produce sounds.

The actions/playing methods used to produce sounds.

My aim in making these maps was to show the complex interactions and potentialities that objects provide as material agents in music making, and to demonstrate how I work and perform with them. The maps illustrate the interdependence of objects and actions, as well as my own musical thinking and categorizing; they also reflect how I intuitively map my vocabulary when I improvise.

The Object Mind Map

First, I mapped sounds through the objects that I used to produce them, as this seemed to me like the most natural and practical way to group sounds.

Lines indicate connections between sounds in the map. I note that I list my hands as an object when I use them without any additional objects to produce sounds with, inside the piano or on the keyboard. As there are many different ways of using one single object, I tried to be as clear and short in my descriptions as possible.

Figure 3: The Object Mind Map

The Playing Method Mind Map

I also produced a second map that illustrates the relation between sounds and the methods or playing techniques used to produce them. I chose to start with the basic sound-producing mechanisms and actions used to set the strings, etc., in motion, including striking, bowing, and plucking. Pressing down the key of the piano, for instance, results in the striking of a string with the hammer, which is a similar method to striking the string with a mallet. In the process of making the map, I soon found that I needed subgroups and had to invent new terms to differentiate between similar playing methods and to describe them in more detail. I was not always able to find them in descriptions of other string instruments’ playing methods either, and some techniques seemed too idiosyncratic to describe by recourse to a general terminology—e.g., the sound produced by making a column-shaped magnet vibrate on a string. Reflecting on my playing methods and the intentions behind certain actions, I noticed a strong aleatoric element. I chose to group those sounds together under the term initiating: after the initial action of setting something in motion, the movement/vibration and sound either continues without any further agency from my side, or the sounding result is in some ways beyond my control, and intentionally so. Of course, one could argue that simply pressing down a key will set mechanisms into motion which, after an initial action are beyond my control as well. However, I decided not to include this playing method in the initiating category, as a pianist’s touch, as well as their ability to stop the sound by letting go of the key, can be very refined and controlled through practice. In contrast, when throwing a magnet on a string, I can, for instance, predict roughly where and how it will land, depending on the angle, direction, and distance from the string, however, there is a lack of control simply due to the magnetic quality of the material itself. Importantly, I found that the attitude or intention behind all of the sounds in the initiating group, whilst connected with other categories of sound-producing mechanisms (in the case of throwing a magnet on a string it would entail initiating as well as striking) differed from the rest of the methods that I use.

Figure 4: The Playing Method Mind Map

An interactive audiovisual version of each map is available in the Research Catalogue exposition as Media Example D1 [Research Catalogue (RC) link here] and Media Example D2. Furthermore, I made videos of most sounds represented in the mind maps and used in the Performative Timbre project discussed in chapters 4 and 5, which are likewise available as Media Example A1 [RC link here].

Jean Baudrillard speaks about “an object abstracted from its function and thus brought into relationship with the subject... such objects together make up the system through which the subject strives to construct a world, a private totality” (Baudrillard 1996, 86, emphasis original). The mental structuring of my sound vocabulary, as is represented in the mind maps described above, is an attempt to capture connections between the objects and actions that constitute my practice. These connections indicate possible compositional micro-structures which are performed with objects and shaped through them. The two maps each have a different focus and through approaching sound and timbre from these two different yet intertwined angles—namely, in terms of objects and actions—different groupings or combinations of sounds take shape. The Object Mind Map details the variations and possibilities performed with each object and shows how, most of the time, several objects are used simultaneously in different combinations. This further suggests a major difference in approaching timbre that can be thought of in terms of (i) thinking in objects, a mindset that opens a variety of timbral possibilities, as most objects can be performed in multiple nuanced ways, covering many different playing techniques; and (ii) thinking in playing techniques, which already implies a certain timbral decision that is made beforehand by the performer, who reaches for a sustained sound (bowing), a percussive sound (plucking), etc., irrespective of which object is used to do so.

The compositional possibilities of the two approaches detailed in these two maps, exist simultaneously and to differing degrees, can be amplified, re-linked, combined, or applied to other objects and actions. The endless nuances of technique are impossible to entirely capture in such maps, yet the attempt of collecting, mapping, systematizing, and repeatedly performing still revealed a myriad of details and suggested a range of possible transitions to me—timbral as well as temporal and spatial. The maps likewise leave out what cannot be shown—a degree of intimacy, which can only be experienced through time. Despite these omissions, I hope that the mind maps bring the process of working and thinking with objects in music making closer to the reader, making it more graspable; this is something that I have sought to do throughout this chapter, by both describing that process through my own memories and through the stories of other practitioners.

Chapter 4:

Performative Timbre

“Performative Timbre” is an intensive listening study of a small selection of my piano vocabulary, which uses a subjective similarity measurement. The study was developed and conceptualized in collaboration with Palle Dahlstedt, between autumn 2017 and spring 2019.

In this chapter, I describe how I performed the study using an adaptation of the Timbre Space method and in line with an extended understanding of timbre. Focusing on my idiosyncratic sonic vocabulary, the project revealed qualities of timbre in relation to objects, playing methods, and the gestures used to produce sound. The enduring and repetitive nature of this comparative listening study generated different listening modes, heightened my awareness of the compositional capacities of timbre in improvised music making, articulated and confirmed my understanding of instrumental technique as described in chapters 2 and 3, and had a transformative effect on my artistic practice.

My aim lay in finding out how and why I group certain sounds together: was this pure habit, or intuition, or a question of personal aesthetics and taste, or simply a pragmatic decision to do with the possibilities and limitations of body and instrument, or was it related to an underlying artistic logic? How do I listen to and structure my sound material in improvised music performance? How do I orchestrate timbre? These research questions are discussed in chapter 1 and formed the outset for this study. Mentally organizing and structuring my sound vocabulary seems natural to me, and I see this as a pre-condition for improvised music; I have never, however, attempted to do so systematically or in such extensive detail as in this study. The tension between creating a sound catalogue, articulating different notions and relationships within its frame, and the obvious limitations such a frame provides, was challenging, yet stimulating and generative in its process.

In late 2017, I made recordings of a large number of sounds produced with the piano, which form an integral part of my vocabulary, and chose 50 sounds out of those recordings to represent through a small, selective, sound catalogue. A custom-built software tool developed by Palle Dahlstedt enabled me to listen to all possible sound pairs in a randomized order, 1,225 in total, and to compare these sounds to each other by focusing on various details and asking specific questions about them. The questions focused on similarity of the sounds in relation to objects, playing methods, physical gesture, and overall timbre, resulting in 4 rounds of listening with a total number of 4,900 sound pairs, which I listened to and compared over a period of a few months. This resulted in four sets of collected data, which are represented in perceptual timbre maps (these are discussed in chapter 5 and are available as interactive maps in the Research Catalogue Exposition).

“Performative Timbre” was possibly the most arduous out of the projects developed during my research, in terms of its conceptual outline, the range of methods that it required, and its artistic implications for my practice. Articulating the process of performing timbre was highly challenging: not only was the process of recording and selecting the sounds that would make up the catalogue intensive, the process of comparing timbre through different performance aspects and qualities, and of describing the possible intentions behind the performance of each sound were lengthy and rigorous tasks. At times,

I questioned the whole notion and benefit of the project. However, in retrospect it is clear that timbre orchestration concerns dynamic, performative relationships rather than the use of defined categories, and “Performative Timbre” therefore frames my entire research, both in terms of the time that it took to develop and perform this work, as well as its capacity to address and articulate theories and concepts relating to vocabulary, technique, and timbre orchestration. It also connects to other projects in this thesis through its use of timbral memory as a generative tool in real-time compositional thinking.

During my research into relevant timbre studies, which are outlined in chapter 2, I came across the Timbre Space method, which is mainly used in the field of acoustics, music psychology, music information retrieval, and computer aided sound synthesis, and can be described in the following terms:

“The term ‘timbre’ encompasses a set of auditory attributes of sound events in the addition to pitch, loudness, duration, and spatial position. Psychoacoustic research has modeled timbre as a multidimensional phenomenon and represents its perceptual structure in terms of timbre spaces.”

The Timbre Space method comprises of a sound comparison, which is undertaken through a perceptual listening and scaling exercise that is conducted by a number of participants. Usually participants compare one sound to another, or, in some studies, sound relationships between pairs of sounds. The data from this perceptual scaling is used as input in computer software using multi-dimensional scaling algorithms (there are various computer programs enabling this). These algorithms translate similarity data into spatial relationships, where the relative distances between elements correlate to their measured similarity. Hence, the Timbre Space method facilitates a graphic representation of the perceived similarities and differences using distance values. Attributes of sounds that are perceived to be similar are represented as being more proximately located in space, and those that are perceived as dissimilar are represented as being further apart. The spatial representation can have any number of dimensions, and a higher number of dimensions allow for a more correct distance representation. For data visualization purposes, 2- or 3-dimensional representations are most common. Grey was among the first to develop and use Timbre Space representations in his research and spoke of a “psychological distance structure” (Grey 1975).[1]

In a perceptional study of sounds to be compared in a Timbre Space, sounds are most often normalized in terms of their pitch, duration, and volume, so that the timbre is the only differing aspect. This is done to reduce difference to only one parameter, and to make it possible to attribute any perceived differences to this particular parameter. These studies often work with and derive independent acoustic correlates of sounds “correlating the position along the perceptual dimension with a unidimensional acoustic parameter extracted from the sounds,” e.g., the attack time, the spectral centroid (the balance between high and low frequencies), or spectral flux, which describes the evolution of the spectral shape over a tone’s duration, etc. (McAdams 2012, 3). Stephen McAdams describes the aim of such studies as lying in the content-based search of large sound databases, providing tools to benefit music information retrieval and musical machine learning applications, musical source identification and tracking, as well as drawing conclusions on timbre as a form-bearing dimension (McAdams 2013, 60, 61). Similar views have been expressed in studies comparing timbre spaces to each other, in the aim to move towards a “stable timbre conception adapted to human perception and independent of pitch and loudness” (Zurich University of the Arts, 2017). Further, new approaches in empirical timbre studies of musical instrument sounds exist, which include the “musical” parameters of pitch and volume. These are described in the following manner:

“This considerable broadening of the data basis for each instrument will certainly lead to results that are (1) reproducible and hence reliable, (2) closely related to the actual circumstances in music, and thus will (3) yield more realistic and universal information about the perceptual similarities of the timbre of musical instruments.”

In general, timbre studies are mostly outside the “actual circumstances in music” and they are usually comprised of sound material that is synthesized, or, if “natural” recordings of acoustic instruments are being used, balanced to make comparison possible. The performance or compositional aspects are generally not taken into account and many other aspects and qualities which comprise a musical context are absent. This becomes problematic, however, when conclusions about the sounds’ function in a musical context, such as the building or release of tension, are drawn. For the purpose of my research, an adaption of the Timbre Space method was necessary, making it possible for me to include performance aspects such as the body and movements of the performer, the materiality of instruments and objects, and likewise consider the impact of different listening modes and approaches, as well as the intentionality of the sounds that are performed or composed.

“Indeed, without a narrative, without the organization of experience, the event cannot come to be. This organization is an organization of temporality...” remarked Susan Stewart (1993, 22). The “organization of temporality” is something which happens in real-time, during the improvisational performance process, which makes it even more complex, as no performance or piece equals another. My aim is thus not to describe or analyze a specific piece, composition, or recorded improvisation. The structure in improvised music changes constantly and the analysis of a recorded improvisation leaves fundamental matters of vocabulary and technique, which form the building blocks of timbre orchestration, untouched. Structure in improvisational music derives from and is embedded in sound material and how it is combined and placed in time and space. Timbre—its spectral, dynamic, temporal, spatial, and gestural information—suggests and opens to manifold musical transitional possibilities. As such, it was crucial that I took into account the development of the material and of my vocabulary, even if these are more nuanced than I was able to capture in a sound catalogue. However, as I mentioned briefly in introducing this method, in retrospect I experienced the process of creating a sound catalogue as generative: in comparing and unfolding the sound material itself through detailed and intensified methods, I gained profound insights into the resulting timbre relationships and their compositional capacities.

In the first and second year of my doctoral studies, I started out by undertaking a spectral analysis of the sounds that I use in my practice. These were both recorded and real-time. In this, I was inspired by compositional approaches in spectral music and the use of programs such as Audiosculpt, Spear, Max MSP, etc. I found that the information provided through this method (frequency and intensity in relation to time) was interesting and added to my knowledge about the sound material. It “sharpened” my listening, as I was able to take sound spectra apart and, for example, selectively and repeatedly perceive one harmonic frequency at a time, which I wasn’t aware of prior to that. However, the further development of the “spectrograms” (the visual representation of a spectral analysis) and their integration or translation into my artistic work did not seem feasible. I realized that I was trying to arrive at physically measurable information about sound material that was fundamentally idiosyncratic. In the process, I attempted to purposefully produce all sounds inside the piano on the same string, for better comparability and to produce somewhat quantifiable results. This would have been in line with Pianist Sebastian Lexer’s approach of summarizing playing techniques. Lexer engages with improvisation, extended techniques, and augments the piano with live electronics. He gives an overview of extended techniques in his dissertation “Live Electronics in Live Performance: A Performance Practice Emerging from the piano+ used in Free Improvisation,” where he writes “...each personal approach shows unique aspects. This selected overview will focus on methods applied to a single pitch in order to draw attention to the differences in approach and sonic variation possible...” (2012, 103). Due to this vast vocabulary of techniques and objects, he decides to:

“…summarize playing techniques, the objects, and preparations employed, and their placements in more general terms with an attempt to establish possible grouping of objects and performing gesture. This employs a stylized notation developed for the purpose that focuses on the relationships between gesture, material, and method rather than considering the sonic outcome alone. ”

In the resulting 28 graphic examples (with accompanying audio) of extended techniques, Lexer generally speaks of “preparations” and “objects” without further specifications, although he gives a few examples of materials and variations used by different pianists in the descriptions. He further distinguishes between silent and sound-producing playing gestures (ibid, 106).

During the course of the “Performative Timbre” project I found that the application of all playing methods to just one string of the piano, in an attempt to produce measurable or quantifiable results, to be unfruitful. It did not represent my vocabulary; many techniques could not be included as a result of this restriction, as they had been developed using a specific object in a specific register, sometimes across many strings, and simply do not work or have the same sonic outcome if performed in a different register. This approach would have been equally as restrictive in relation to timbre as it was in relation to register and technique. The method of applying all sounds to one string fundamentally changed the way in which I performed the sound material, gesturally as well as sonically. Instead, I decided to embrace the idiosyncratic way that each sound is performed, taking into account that the sounds would differ in relation to most perceivable parameters, which would produce bias in the comparisons and ratings as part of the “Performative Timbre” study: sounds are played in a variety of registers, volumes, and durations in order to reveal and maintain their identity and the aesthetic and intention with which they are performed. This required that I arrived at a subjective similarity measurement methodology, using sound material which was not synthesized or made comparable in any way, as well as being the only subject who would record, choose, compare, and rate the sound material.

As described above, the spectrograms lacked perceptual and experiential aspects in their analysis as well as their representation. Furthermore, the method left many aspects of performance untouched, such as a performer’s relationship to the instrument, the materiality of objects used, as well as the gestures and movements involved in sound production. It became clear that a sound catalogue would have to be structured in a way that related to the idiosyncratic thinking and creating within my artistic practice.

Initially, I struggled with the contrast between a “scientific” versus a phenomenological or “intuitive” approach, in part reflecting the fact that a lot of studies around timbre take place within the fields of music psychology, acoustics, or audio engineering. Arriving at the point where I could embrace a subjective, experiential method, which was integrated and derived from my practice, was admittedly a very difficult process and meant positioning myself and this study clearly as an artistic and phenomenological approach in music performance and timbre research. Thomas Clifton compares scientific and phenomenological approaches, advocating that:

“the question is not whether the description is subjective, objective, unbiased, or idiosyncratic, but very simply is whether or not the description says something significant about the intuited experience, so that the experience itself becomes something from which we can learn, and in so doing, learn about the object of that experience as well. ”

I have approached sound material from various angles in my research and within the different projects that I have developed. In this study, it became essential to shift to a performative approach, and to embrace the situated knowledge I could gain from that position rather than adding to the vast research on timbre which already exists in other fields. As a performer and improviser/composer, I am in the unique position to offer insights into the perception and application of timbre within my artistic practice, inside changing dynamic relationships of space, material, and body.

The tension between the need to create a sound catalogue and the unattainability of performing, capturing, and articulating all the nuances and variations of sounds accompanied me during many steps of this study. Questions I struggled with in the research process related to which and how many sounds I would choose to conduct the listening comparisons, which aspects and qualities I would compare, and whether this would partly be defined by the language I chose. I was further thinking about ways of describing and articulating timbre, but also about how I might address the nuances and details of my physical gestures without necessarily inventing a new terminology. At the same time, I found deep pleasure in the process of systematizing vocabulary and techniques and articulating perceptions and intentions. “The catalogue itself,” Baudrillard reminds us, “however—its actual existence—is rich in meaning: its exhaustive nomenclatural aims have the resounding cultural implication, that access to objects may be obtained only via the pages of a catalogue which may be read through ‘for the pleasure of it,’ as one might a great manual, a book of tales, a menu...” (1996, 4).

A catalogue is a very seductive idea and the impossibility of ever completing it has made the process and its limitations and possibilities, what was missing and what was gained, a fruitful one. Investigating timbre, unfolding it into detailed components through endured, repetitive listening, revealed its intention and capacity to create and function as a dynamic, interactive agent.

The perceptual approach in the Timbre Space concept is something that I found very appealing and suitable for my purpose of understanding the way I use timbre in musical structures. Even though its goals and application differ largely from my own artistic research, I chose to adapt its method and create the “Performative Timbre” study instead. Comparisons are always concerned with relationships and my own research investigates timbre in relation to performance aspects and aims to bring these interdependencies to the surface.

My aim has not been to draw quantifiable conclusions about inside piano sounds and their timbre. As such, I did not synthesize or balance the sounds that I used regarding duration, volume, or pitch, as that would impact their idiosyncratic character. I also refrained from extracting audio features and measuring sounds via computer software as part of the analysis and focused only on the experiential and perceivable aspects of my sound vocabulary. Furthermore, because this thesis addresses an extended understanding of timbre, I ensured that this was reflected in the questions that I asked regarding material/objects, playing method, and gesture.

Recording and selecting

Through the structured inventory list and sound maps that are described in chapter 3.4, I had roughly decided which material, sounds, and techniques to record. The recordings were made over a period of a few days in December 2017, in my living room in Berlin, using the same setup and microphone positions. The microphones used were two Neumann TLM 103 microphones and a Focusrite Clarett 8 Pre sound card with a Schimmel grand piano, model K175. During the entire study, I used the same headphones, Sony noise cancelling MDR-NC 13.

Figure 5: Setup for recording sessions for Performative Timbre, Berlin, December 2017

I tried to mix the recordings as little and close to my listening as pos sible, so that the recordings would not be over-produced, sometimes using both microphones, sometimes just the one closer to where the sound was initiated. I wanted to tailor the recording to my perception of performing the sounds. I occasionally used a compressor to bring out more details and make softer sounds or attributes louder. Each sound was recorded numerous times, sometimes requiring 20 takes of simply plucking a string until I found the sound was captured in a way that was satisfying. The working process created and required a mindset where every little nuance mattered.

December 28, 2017

I record some of the sounds 10 to 20 times. Listening to the details of the many recordings, for example a tiny cube magnet in the middle register sitting on two of the three strings of one note, I notice something I haven’t observed before: the multi-phonic which I hear in the attack stays throughout the sustain part of the sound, but as the sound decays, it “resolves” the harmony and sounds only the fundamental.

I asked myself what constitutes a “perfect” recording and execution of a sound; would I cut out any extraneous noises, turn the sound into a “clean” sample? Or treat the recording as a performance, and accept the situatedness of each performed sound?

Going deeply into the details of performing the sound was an extremely valuable process, which made me listen with more precision and attention. It revealed aspects that I was not aware of. The entire process of the study continued to reflect back to the questions I set out with as part of “Timbre Orchestration”: How do I articulate intimate and interactive processes of technique and vocabulary?

December 27, 2017

This is not a catalogue of extended techniques, it’s a Material Action Timbre Study. It’s not a guide for composers or performers, nothing to apply and imitate directly, but rather something to inspire, a method showing how we can think about and apply timbre.

I ended up with a few hundred sounds, including many variations of the same sound. At times I would record, listen, and record again, selecting the sounds that I found aesthetically pleasing and representative of a specific technique I wanted to include. During the process of the study I was struggling with the fact that this sound catalogue could only be representative of a fraction of my sound vocabulary, and that I had to be selective with respect to the material. This confrontation with an obviously endless variety of sound material and timbral nuances of a single playing technique revealed the fact that technique must be re-invented and re-learned every time it is performed; an approach and a mindset of heightened awareness and flexibility to performance circumstances.

December 30, 2017

In the end, I can’t separate an action from a movement, a memory, or a sonic image I have of a sound, from my taste, my aesthetic choices. That’s what this is about. Finding out about my choices and the reasons behind them.

In discussion with Palle Dahlstedt, I finally decided to cut the catalogue down to 50 sounds, considering the sheer number of listening comparisons I would have to do. In the selection process, I realized how some actions reflected a learned habit, both physically, i.e., through muscle memory, and mentally, which is often so embodied that it is not separable from my personal taste.

This reflective and microscopic listening and selecting of many differ ent versions of the same sound suggested adjustments and changes, or reassurances of techniques and choices, in direct connection to my performance and artistic process. I tried to capture thoughts and observations in a “listening journal,” which was very much part of the entire study—this formed a continuous, reflexive protocol which I kept while listening, pausing, repeating, writing, and listening again.

December 28, 2017

Trying to record sounds in a “neutral” way, meaning, in a sense “pure.” Or is it OK to have extra sounds and noises, the mechanics of the sound production as part of the recording, like the sound of a guitarist’s finger tapping and sliding on a string or the breath and spit of a reed player? A well-played sound, a well-executed sound: a sound that transmits its idea—it must be clear, without second guessing. It will still be magical, but not random. Technique means detail and intimacy. That’s virtuosity. Being able to hear and perform as nuanced and detailed as possible. Movement and object and sound in line, corresponding.

It was interesting for me to discover that I seemed to prefer sounds which were performed with a certain decisiveness, separate from a “clean” or “perfect” technique and how a single sound can convey that, even in a recording situation which was meant as a demonstration of a playing technique. Every performance happens in a context, or rather performing a sound means contextualizing it. There are external factors in the environment which influence a performance, as well as the knowledge and experience brought into it and all that is perceivable in the simple action and recording of pressing down a key on the piano.

December 28, 2017

This is meticulous work! Which one sound to pick? Not as a representation of all. Coming back to that over and over again. This is not a full catalogue. It’s a snippet, an excerpt, a study.

January 2, 2018

Stop looking for the perfect sound! The constant doubt, whether I should record and capture more nuances, the sound played softer, slower, more fragile, longer, with a different attack? The basic need to contextualize, I guess.

The endured recording and listening process felt like an intensive practice and a study in focus as well as memory. Having to decide which sound out of a batch of 20 to pick meant remembering sounds and movements and mentally building up a catalogue of myriad nuances, almost as a repertoire, enriching my vocabulary. These lessons in timbral memory enhanced my abilities in listening, perceiving, and creating, focusing on my initial research outset of unfolding improvisational structures and orchestrating timbre.

Software Tool

To conduct the study, Palle Dahlstedt built a software tool which enabled me to listen to all possible sound pairs out of the 50 chosen sounds in random order. I would then give the pair a (dis)similarity rating based on different perceptive performance qualities and the questions I had placed at the center of the study. The tool randomly picked sound pairs, without revealing the names or descriptions of the sounds I was listening to. I then compared sound A to sound B and rated it on a scale from 0, very different, to 1, very similar. The tool stored my ratings and I could go back one step if I thought I made a mistake, which enabled me to conduct one listening session over a longer period of time. One question or listening round would make up 1,225 possible sound pairs, which I compared and rated accord ingly.

Figure 6: Screenshot of the software tool used in Performative Timbre developed by Palle Dahlstedt in collaboration with the author

This way of randomizing the order and listening to sound pairs in all possible combinations also enabled me to hear each sound in many

different contexts and to observe how it changed perceptually in response to what I had listened to prior to listening to it, taking on different meanings and impacting my perception of it. Another function built into the tool was playing sounds simultaneously, overlapping them, or listening to them in succession.

As mentioned above, the 50 sounds that I used in the study were partly based on the mind maps (see Fig. 3 and 4). Further, in the recording process, I would pick the sounds which were aesthetically pleasing or representative of a certain technique I wanted to show. After selecting the 50 sounds, which I describe in detail in chapter 5 and make available in the RC exposition, I decided on the questions I would ask.

How similar are the sounds to each other, in terms of the objects used to produce them?

How similar are the sounds to each other, in terms of the playing methods used to produce them?

How similar are the sounds to each other, in terms of the physical gestures made to produce them?

How similar are the sounds to each other, in terms of their timbre?

There were some questions, e.g., regarding the possible functionality of sounds, which I was interested in pursuing, but which proved to be impossible for me to answer at the time, or at all.

I wanted to investigate whether I could use certain sounds or materials only in certain contexts—i.e., as textural elements, as layers, exclusively in combination with other sounds, as transition material, etc.

January 4, 2018

When does a sound become a phrase, a fragment, a texture? Any sound becomes a texture when it’s played long enough, repeated or played with little variation, but I don’t use just any sound for that purpose. Either, because I don’t think every sound lends itself to be used texturally or because of pure habit.

I was wondering whether certain sound material lends itself to be used in one context more than in another. However, this way of thinking, especially in improvised music, seemed restrictive to me and triggered the opposite effect in terms of a structural compositional approach: it opened my imagination in a way that I want to think of any sound to be used in any way at any time. The restriction does not lie in the sound material itself but rather in the musical context and what seems appropriate at the time, to the performance space and circumstance.

Another obvious question concerned the comparison of the spatial projection of the sound material. However, this differs immensely from space to space, instrument to instrument, listening position, whether I choose to use the sustain pedal or not, etc. It seemed to me that there would be too many variables to draw any conclusions from, and I decided not to apply spatial projection as a parameter in the listening comparisons. Instead, I used the four guiding questions raised through reflection on the mind maps.

4.5.1 Question 1

How similar are the sounds to each other, in terms of the objects used to produce them?

“Sense is already built into objects by virtue of their form, their morphology.”

The question of how similar sounds are to each other, when considering the objects which produce them was an obvious first question for me to ask, as it reflected how I would naturally systematize and define sounds; it was perhaps also the easiest one for me to answer. To be consistent in my similarity ratings, I added “rating rules” during the listening process, which I describe in detail in chapter 5. As an example, I decided to rate sounds as being “half similar,” if they shared an object in the sound production, as some techniques utilize more than one object to produce sound.

One main impact that “Performative Timbre” had, and which I experienced during the process of undertaking the study, was to change the levels of listening and focus that each question generated and required. In this first round of listening, I had to be careful not to confuse the object used with the method used, in my perceptual rating. Again, I noticed so many details and subsets of performing the vocabulary, which sometimes made me go back and forth and second-guess my choices and ratings until I found a comfortable pace or rhythm of listening. While comparing sounds through the objects that were used to produce them, I felt I was getting closer to my understanding of the relationship between sound and material and how this interdependency unfolded.

May 12, 2018

Is rosin an object? Or is it facilitating the use of other objects? It is material, I put it on my finger, it is powder, it turns into a sticky layer, it’s an object covering my fingers and the string. Is there a difference between passive and active use of objects? Is an object passive if it’s just placed somewhere to resonate—isn’t that an intentional activity as well?

4.5.2 Question 2

How similar are the sounds to each other, in terms of the playing methods used to produce them?

The mind map of different playing methods which I drew prior to the listening test was very helpful in understanding similarities between sounds and methods. However, I had to rethink many of the groupings and again, I had to make sure that I did not confuse the playing method, or action, of how a string is set in motion, with the gesture and movement used to produce the sounds in my perceptual rating. It also meant defining what a playing method actually implied for me, and, as described in chapter 3.4, it made me rethink how I would label and group the actions. This sometimes resulted in long discussions with colleagues and contemplations about different ways of plucking a string, minute details of its action and appropriate names regarding, i.e., other string instruments and playing techniques.

June 5, 2018

Bowing scraping, striking, plucking, initiating, strumming, tapping ... techniques overlap. Even though an EBow produces a sustained sound it is not bowing! It’s initiating. What’s the difference between scraping and bowing? Is it about noise, the material used, or the friction?

Strumming equals plucking, except strumming is a horizontal and plucking a vertical movement.

Bowing involves: longitudinal bowing, vertical bowing, bowing with other objects from left to right across the strings. Why is it all the same? Exciting the string through movement continuously over a sustained period.

4.5.3 Question 3

How similar are the sounds to each other, in terms of the physical gestures made to produce them?

Firstly, the question of the presence of similarities between sound and gesture revealed big discrepancies between physical movement and timbre. A “small” gesture, a barely noticeable bending or pressing down of my finger, could have very different results: in the case of setting a fork stuck between the strings into motion, this produces a long-lasting, vibrating, textural sound. But a similar gesture that lets a magnet strike the metal frame inside the piano results in a percussive, loud, and relatively short sound. Listening with this question in mind, I would perform the gestures and movements, which produced each sound, silently, in the air in front of me.

July 17, 2018

The different questions require different modes of listening. It makes me think about the force and energy used to produce certain timbres, the effortlessness of other movements. How much space does a movement take up? Does it have the same direction? How long is the gesture, its duration, its tempo? Is it about physical movement or about how it feels or about what it looks like?

François Bayle sums up the different aspects of physical performance and its effect on music and the listener in the following terms: “In the studio, we are provoked by the conditions there, by the various interfaces provided by the technical tools. So, I would say there are two major periods in my work: the standing period and the sitting period. This difference in work habits made for a different music. It is perhaps idiotic but it is true!” (in Desantos et al. 1997, 17). Even though he is working in the electronic music field as opposed to the (electro)acoustic, I could very much relate to this: sitting or standing at the piano results in immense differences in movement and sonic outcome each condition affords or limits.

July 17, 2018

Am I sitting down or standing? Am I straight standing or bent over, am I using one or both hands? That is an important factor in making musical transitions, it affects the overall structure.

“Like a painter, my music is also the product of my hands, ultimately. My spirit selects and saves what my hands do,” states Bayle, “but it is the hands that perform the work. These imperfect gestures shape the sound’s morphology and serve as signs to the listener” (ibid., 18). While in Bayle’s acousmatic work the physical gestures might not be visible, but can be aurally perceived, I also feel the weight of the bodily and visual aspect of my performance, what it transmits, how it shapes the sounds and influences the perception of the listener, which was all amplified through this listening round and this specific question.

July 28, 2018

Sometimes gestures can have the same kind of momentum to them, performed with the same attitude, the same pace, the same weight, yet produce very different sounds. It matters with what intention the movement was performed.

The exercise had an incredible effect in regards to bodily awareness, and, for the first time I began to think about physical micro-structures, and how I lacked a language to describe all the different nuances of bending a finger, turning my arm or body, of physical tension, of different grades of weight, and falling and releasing. It also connected to other projects I started developing at the same time, such as Accretion, which is discussed in chapter 8, where physical gestures and bodily movements are partly separated from sound and used to structure a performance.

4.5.4 Question 4

How similar are the sounds to each other, in terms of their timbre?

The question regarding the similarity between sounds with respect to their timbre in a way sums up the study: after taking the sounds apart and looking at different aspects of sound production seperately—objects, actions, and gesture, here I was trying to listen to the sounds in a way that included all of these aspects again.

This was probably the hardest question to answer, and the listening round took a long time, because I felt that I was relying almost exclusively on my intuition and that my answers would differ from day to day, or mood to mood. I constantly had to remind myself not to be influenced by other perceptual aspects and qualities in my rating, e.g., not to rate two sounds as being similar in timbre because they were produced with the same object. This was however a very interesting discovery—the same playing techniques or objects did not necessarily mean that I perceived the sounds to be similar in timbre. I took a long time taking the different “measurable” elements of the sound—volume, pitch, duration—apart mentally and listening to them analytically, separately, and then focusing on the sound as a whole again. Here, the overlapping function in the tool was of great help, and I would often trigger sound A and B at different times so that they would overlap during different phases of the sound. I sometimes spent 5-10 minutes with one sound pair, going back and forth, taking a break and coming back to it, while at other times it only took a few seconds to rate. Deciding on a consistent rating system was also challenging, as this question was particularly perception-based and I was left with no technical or material aspects of the sound to hold on to. I often found that sounds would differ in timbre despite having the same pitch and that, again, the intention with which it was performed had an impact on my rating.

July 15, 2018

This study somehow becomes a meditation, an exercise in focusing. Comparing the similarities is about revealing possible transitions and structural choices, the transitions existing within the sound, the change of energy, noise, pitch, and volume, the fluctuation that suggests what can follow. I noticed things in the sounds I haven’t heard before, frequencies, nuances—the comparisons reveal things.

July 17, 2018

I’m imagining transitions systematically. A lot of this has to do with memory, sound memory: for example, is sound A as similar to sound B as sound C is to sound D?

Intention of course entails dynamic and temporal aspects, etc., but it also made me realize how the timbre question was perhaps the most “musical” one—meaning that I heard and imagined the sounds very much in a context and not in isolation. This is perhaps because the concept of timbre consists of so many parameters that we judge musical: rhythm, pitch, harmony, and dynamics experienced over time and through space. Sounds also relate to the complexity of both immediate and long-term artistic feedback in the creative process through listening, playing, body, and memory, and in the nature of this listening study it raised reflections on repetition.

A repeated sound is never identical; even when it is looped, it will be perceived differently each time it is listened to. Repeating a sound, as a structural tool in music making, changes our perception of what came before and what follows. Repetition affects our relationship to time and creates variations and textures, separate sounds develop into textures over time, and subtle timbral, dynamic, rhythmic, and spatial differences and nuances emerge.

Joseph O’Connor speaks about repetition as a “celebration of the particularity of every event… Repetition becomes an invitation to pour attention into the texture of the sound while also sculpting discernable relationships between musical participants” (2018). In “Performative Timbre,” listening and the creation of different listening modes took a central role. This implied a different focus and perception of time: through this endured listening exercise, whereby 50 sounds were repeatedly compared to my memory of them, as well as how they differed or appeared similar, I found myself perceiving a fluid sense of time, almost like a meditation: a sense of being “in the moment.”

In the beginning of the process, I asked myself whether I could perform the study. The process of listening to myself performing, which I captured in a journal through a performance writing, and which is then represented in the perceptual timbre maps, seemed like a removed action—removed from my actual practice with the piano. However, in retrospect, I feel that this meditative state of remembering and listening and simultaneously responding to it, creating a timbral memory, seeped deeper into my performance. Even though I describe this as an inherent part of improvisation as such, this study heightened the awareness of this process, and the focus gained from it constituted the real benefit.

“I always try and disconnect things from each other. Often my temptation is to bring disparate kinds of materials into the space: text, images, costumes, materials of space and so on.... For me there is a desire to keep stuff separated out, so that as a viewer you have an active and fecund job of reading between separated objects. The work of combining hasn’t quite been done for you. ”

This quote from Tim Etchells about his approach to performance reflects my experiences whilst undertaking this study: in separating and taking things apart, not only did I gain a lot of insight into the tiniest details and micro-structures of different aspects of my performance, but I was also presented with the task of making connections, of imagining how the gaps between gesture and timbre and object could be bridged and how these things could be set into relation.

Initially, the subjective nature of the study made me question the relevance and value of my findings for others. In a break from listening, I went to a photo retrospective on Diane Arbus and in the descriptions on the gallery wall found this sentence, which resonated with me: “...In a seemingly contradictory way, the more specific a photograph of something was, the more general its message became.”[2] It seems to me that a meticulous attention to detail in one’s own artistic work and research is imperative to revealing anything valuable about it. With this in mind, idiosyncratic and subjective approaches are revealed to be both valid and in fact necessary to expose meaning that can affect and interact with artistic processes in general.

July 9, 2018

I start hearing the listening test as a piece of music, how the sounds complement each other or not. How it sounds within a musical structure is a side effect of the study. Or is it the purpose? Which part of the sounds are similar? How could it move from sound A to sound B? Where do they overlap?

As mentioned earlier, I found Tristan Murail’s description of a sound “as a field of forces” (Murail 2005, 122), as simple as it might seem, to be very much in line with my thinking. The 50 sounds that I listened to

over and over again, with their different attitudes, aspects, and contexts had turned into a dynamic energy that allowed me to re-think, re-feel, and re-perform them. The adapted and extended Timbre Space method allowed for detailed observing and thinking about timbre and revealed so much about the selected sounds and how I perform them. As a result, I started seeing connections and interactions between movement, timbre, and material, as well as links between the physical, aural, and visual in my work. Creating a sound catalogue, then, is a process which is not finite, even if its limited frame suggests this: the necessary limitations, reducing and selecting in turn, opened possibilities which set things in motion and affected my overall creation and composing abilities as a performer.

To practitioners as well as listeners across disciplines, the study offers a method of approaching (sound) material and engaging with it in a focused, detailed, and performative way, showing its relational properties through a comparative listening or observing, and its relevance for proposing possible transitional and compositional structures. The paradox of needing to take things apart, dissemble them into detailed components, in order to be able to see their connection to the whole became very clear and pronounced during this study and can be seen as one of its key outcomes.

“Performative Timbre” created a variety of new listening modes and an overall, enhanced perception of sound material and performance approaches, as well as confirming and articulating my theoretical approach to technique and vocabulary as idiosyncratic, multi-sensory, and in a state of continuous transition. The project further confirmed my extended understanding of timbre as a presence and force in music making and listening, detailed through its relationships to material, gesture, and playing method.

In chapter 5, I turn to a discussion of the visual representation of the collected data in four perceptual timbre maps and give further details on the rating process and its implications for artistic processes.

Chapter 5

A Catalogue of Shapes and Motion