Death, Sex, and the Semitone in Monteverdi’s “Pur ti miro, pur ti godo”

Death, Sex, and the Semitone

In Monteverdi’s “Pur ti miro, pur ti godo”

Amazing Moments in Timbre | Timbre and Orchestration Writings

by J Marchand Knight

Published: February 3rd, 2023 | How to cite

In this edition of Amazing Moments in Timbre, I will explore the timbral representation of sex (and maybe death) in “Pur ti miro, pur ti godo,” the final love duet between Poppea and Nerone in Monteverdi’s opera (on a libretto by Busenello), L’incoronazzione di Poppea.[1] Martha C. Nussbaum, in Upheavals in Thought (2012), describes the duet as “an extraordinary depiction of lovemaking,” presumably in part because of the tension and release created by the numerous harmonic clashes and resolutions in the piece. Meanwhile, music librarian and blogger Pessimisissimo interprets the dissonance as follows:

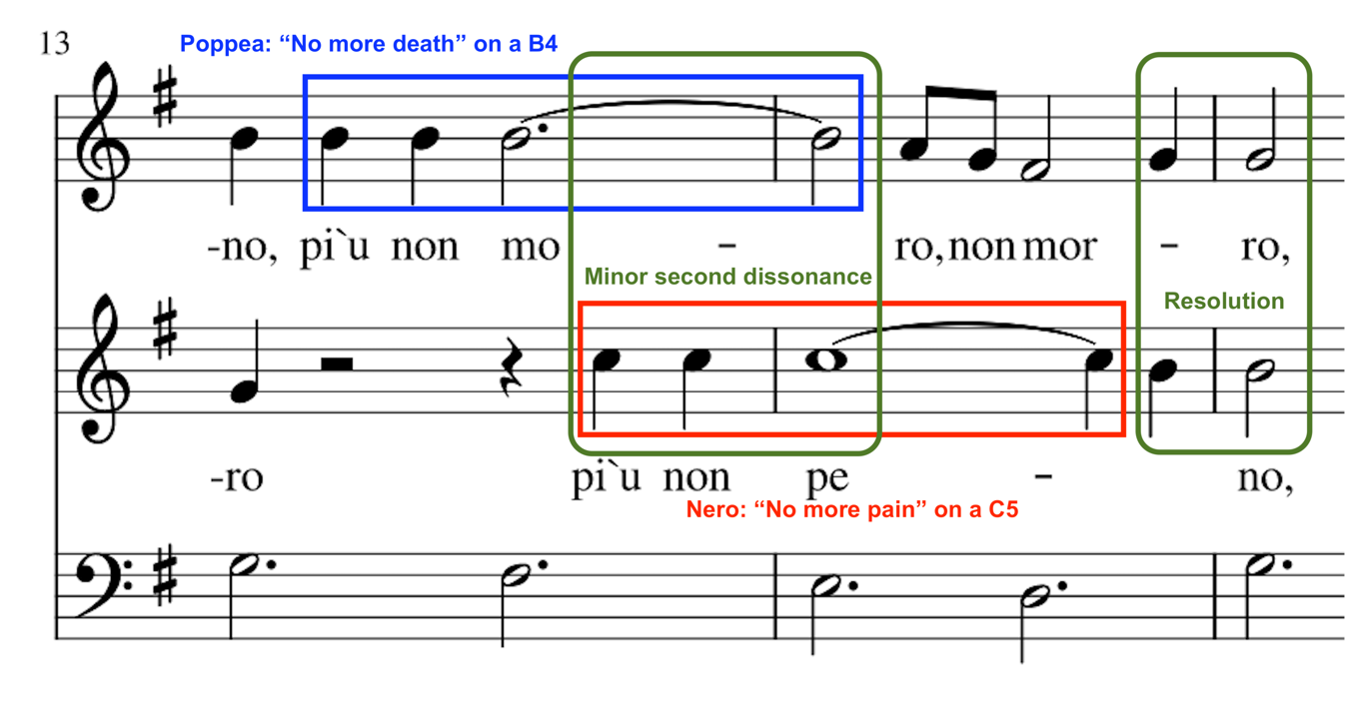

Knowing that listeners couldn’t help but experience some cognitive dissonance, Monteverdi* included some musical dissonance to underline it. As Nerone and Poppea sing “Più non peno, più non moro” (“No more pain, no more death”) their voices clash on “pain” and “death.” The opera may be ending “happily” but there will be plenty of pain and death to follow. (2009)

In my first year studying early music voice as an undergrad, I was assigned the upper part of Poppea in the duet “Pur ti miro, pur ti godo” (I gaze upon you, I desire you). My duet partner, a cisgender woman and mezzo-soprano, sang the bottom part, Emperor Nerone (but this character was a man?!). This all required some unpacking because at the time, I knew little of the pants roles of Mozart and Strauss (roles intended for cisgender women in drag to play teenage boys) or about the bizarre sociological phenomenon of castrati singers (cisgender men castrated before puberty to maintain their prepubescent singing ranges and timbres). “Oh yeah!” said my teacher, who, like me, was part of the queer community, “Sometimes Poppea was also played by a castrato because women weren’t allowed on stage in some parts of the world. So…” she paused and smiled, “…now we cast two women in these roles a lot of the time. That way nobody gets castrated and it’s still gay.” I had hardly wrapped my brain around this when my teacher also told me that “Pur ti miro” had been banned for being too erotic. “All those semitones,” she said.

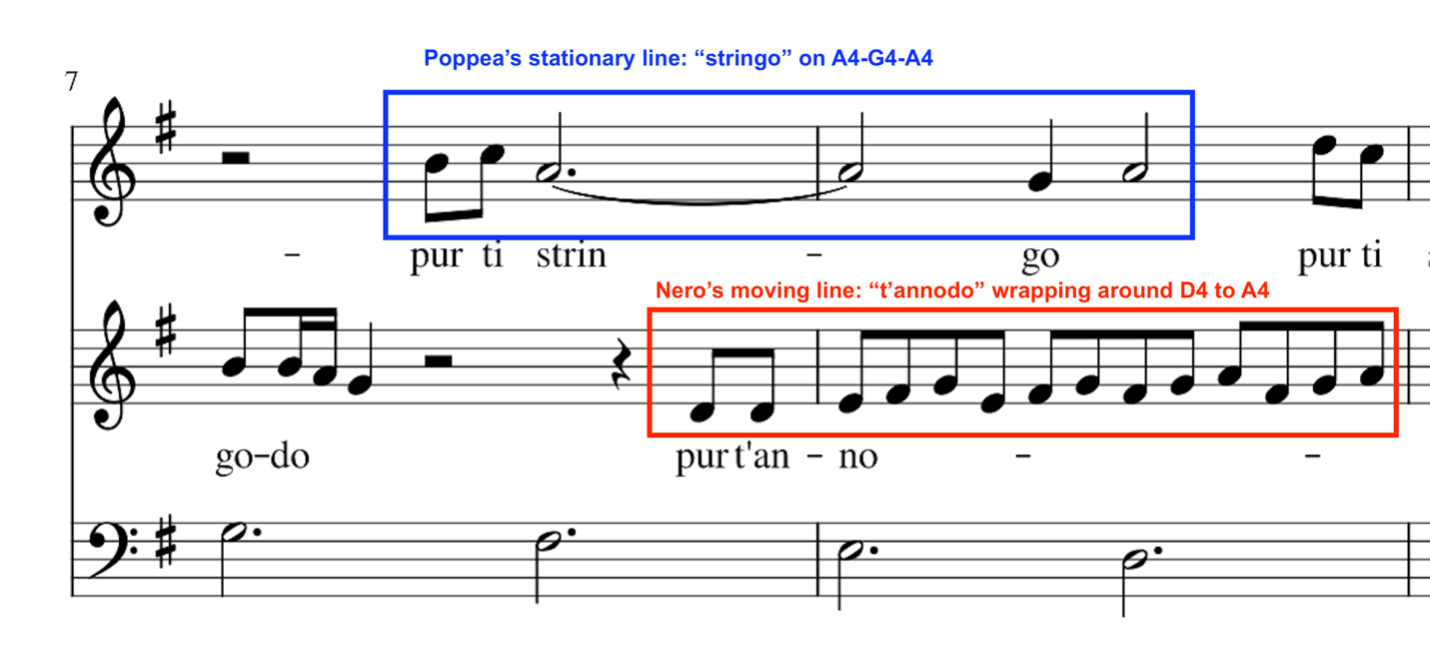

Before we delve into timbre, a bit more historical context is worth exploring. Monteverdi is an important symbol of the transition from Renaissance to Baroque. Although Monteverdi did not, in fact, invent opera, he is credited with planting the seeds of many important operatic conventions, such as the recitative-aria form and the leitmotif. He also had a special gift for word-painting. He did not simply unite text and music; he physically shaped the music to depict the text. This is evidenced by the way he set the word, “t’annodo” (I encircle or enchain you) in “Pur ti miro.” Here, Nerone’s line moves up and down continuously from D4 to A4, circling around Poppea’s stationary G4 and A4.

L’incoronazzione di Poppea premiered in 1643 at the Carnival of Venice. It was a piece of historical fiction, based on the affair and subsequent marriage of Emperor Nero (37AD–68AD) and Poppaea Sabina (30AD–65AD). Precisely this sets the opera apart from most operas that predated it, which were largely based on mythological or biblical stories. Another unusual thing about this piece was that both Nerone and Poppea, were unprincipled, murderous, and ambitious –that is, neither “hero” in this story was redeemable. In the operatic version of our story, Nero and Poppea force the royal advisor Seneca to commit honourable suicide when he opposes their affair. With Seneca out of the way, they send the reigning Empress Ottavia into exile. Poppea then promptly divorces her husband, Ottone and marries his best friend, Nero. The opera ends neatly, after three acts, with what is widely regarded as one of the most beautiful love duets in all of opera, “Pur ti miro.”[2]Here, evil deeds are rewarded. You see, the Carnival of Venice was a bit like Mardi Gras: a last hurrah before Lent. Therefore, a story about sex, murder, and indulgence was the perfect entertainment before a long season of abstinence, and “Pur ti miro,” like the Mardi Gras pancake, has been leaving a strange taste in the mouths of audiences for centuries.

But back to those sexy semitones –and what makes them so sexy.

Conductor Erin Helyard, as quoted by Nick Galvin, says, "It has all these lines that bump and grind against each other. It is so erotic, so sensual." (2017, paragraph 5). Helyard makes an important point: Poppea and Nerone were scored in the same octave and originally intended for singers of similar treble voice types, creating suspensions that result in a semitone-to-third pattern of dissonance-resolution.[3]

“Matching the pitch of the male soloist with that of his lover… makes the duet, to modern ears at least, unusually distinctive and effective” (Galvin, 2017, paragraph 7).

What Helyard misses in his analysis is that the singers should also be a good timbral match for one another. This means that the casting director needs to listen for voices that meld together or voices that complement one another. Voices that are very similar in brightness or darkness, for example, can lead to a type of blend, where we can’t tell one voice from the other, and thus, one body from the other, as they essentially become one sound (timbral emergence). These same vocal qualities can also balance one another, fitting together like big and little spoons, but we can still tell when Nero’s voice dominates Poppea’s, and when his voice becomes subordinate (timbral augmentation). As Maria Rika Maniates points out, this is some “graphic word painting” (Mannerism in Music, 1979, p. 424).

Another factor that is crucial when casting singers in these two roles is vibrato. If the speed of pitch oscillation of one singer is faster than the other or if the ambitus of pitch oscillation is considerably wider, the semitone spacing is not maintained and the duet becomes muddy. As such, this piece is often performed with, what singers refer to as, ‘straight tone’. This not only helps maintain the harmony but supports the blend as well. This term is misleading as it does not mean the tone is devoid of all vibrato or vibrancy but simply that the singers minimize and match vibratos through technique when they know there is an important dissonance coming. In the image below, you can see how Poppea holds her vibrato until the suspension resolves (straighter lines during the dissonant portions, wigglier ones at the resolution).

Notice in the excerpt in Recording 1, Poppea’s entrance at 35 seconds, which begins the section. Nero then begins the repeat at 0:45. This leads to Nero’s unprepared C4 at 1:05. Note that this is also the section referenced by Pessimisissimo: “no more pain, no more death.” His interpretation of the C against B crunch is interesting – he believes Monteverdi is foreshadowing Poppea’s murder with a nasty timbral effect.

Recording 1: Score video of the “pur t’annodo” section of “Pur ti miro,” sung by Elin Manahan Thomas and Robin Blaze. [click to open]

I had only ever considered the harmonic tension-release effect leading to even greater tension and release as a metaphor for lots of (ahem) good sex. To have a (musical) climax on the word death would hardly have surprised Baroque audiences. They would, no doubt, have been familiar with “La Petite Mort” (the little death - a euphemism for orgasm). Many, many, many examples of this exist in Renaissance and Baroque music such as Dowland’s Come Again, Sweet Love, Arcadelt’s Il bianco et dolce cigno and Purcell’s “Bess of Bedlam.”

Recording 2: Camera XV performing John Dowland’s song, Dowland’s “Come Again, Sweet Love,” starting with the first iteration of the “to die” section. [click to open]

Furthermore—and here is the really juicy part—Monteverdi’s semitones cause more than a perceptual response in listeners. They create an undisputable physical response called sensory dissonance, which would not occur if Nerone’s part were transposed down an octave. In music, the term “dissonance” has two principal meanings. The first is “stylistic instability, tension, ‘disagreement.’” (Hutchinson and Knopoff, 1978, 1979) In the context of this definition, consonance refers to elements that are “stylistically ‘stable,’ ‘reposed,’ or ‘in agreement’.” (Hutchinson and Knopoff, 1978, 1979) The second meaning, which may be termed “sensory” dissonance, refers to the sensation of rapid beating, or roughness, within a sonority. Consonance is the absence of such beating. These two definitions do not necessarily agree. The interval of a perfect 4th, for example, is considered to be dissonant in common-practice tonal syntax, since it is unstable when it occurs in a two-voice texture or above the bass in chords with three or more notes. In terms of sensory dissonance, however, it is consonant since it has a very low degree of perceived roughness. The minor second (figure 3), on the other hand, is dissonant according to both definitions (Ferguson, 2000, p. 23).

The sensation of beating to which Fergusson is referring happens when two pitches that are very close together—that is, within the same critical band—stimulate overlapping parts of the basilar membrane in the cochlea (in the inner ear). Our brain cannot process this conflict and understands it as beating (see figure 4). Semitones are especially interesting beasts because while they are close enough in frequency to be within the same critical band, they are outside of the Just Noticeable Difference. This means they are far enough apart to cause different neurons in the brain to fire in phase with their respective frequencies. All of this creates a rather big physical response to a teeny, tiny interval. While what we hear (the sound of dissonance) is perceptual; something very real is happening to our bodies and with that comes a tangible, physical sense of relief when the semitones resolve. Fascinating, no? Renaissance composers were using these sensory responses intuitively to create affect in music, the goal of which was to effect a change of mood in the audience.

Interestingly, I’ve now had the opportunity to sing both roles in this duet because, as I mentioned above, the ranges of both parts are almost the same. Depending on the vocal weight and colour of the singer I am paired with, musical directors might opt to have me top or bottom my partner (a little more queer humour for those in the know). There is something intuitive singers do once they understand the effect of the dissonance-resolution pattern in “Pur ti miro” – it’s what I might call leaning into the dissonance. Basically, we crescendo together into the roughness to build intensity and then decrescendo out of it, coming to a smooth, sleepy, and oh so satisfying end. As a performer, everything I learn about this piece, including Monteverdi’s mysterious understanding of sensory dissonance, helps me make it a little sexier.

Recording 3: Les Arts Florissants performing “Pur ti miro, pur ti godo,” with Sonya Yoncheva, Poppea; Kate Lindsey, Nerone; William Christie, conductor; Jan Lauwers, stage director and choreography [click to open]

References

Camera XV קאמרה 15. (21 June 2016). Camera XV - קאמרה 15 - John Dowland, "Come again" [Vidoe]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/sHGFgAFPFso?t=22

Ferguson, S. (2000). Concerto for Piano and Orchestra. PhD diss., McGill University.

Galvin, N. (27/28 November 2017). “Pinchgut Opera's the Coronation of Poppea is a Tale of Sex, Death and Obsession”. In The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved from:

https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/music/pinchgut-operas-the-coronation-of-poppea-is-a-tale-of-sex-death-and-obsession-20171127-gztrji.htm

Harmonia mundi music. (4 September 2019). Monteverdi, L'Incoronazione di Poppea "Pur ti miro" | Sonya Yoncheva, Kate Lindsay [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/quhXDVX6jjA

Hutchinson, W. & Knopoff, L. (1978). The Acoustic Component of Western Consonance. Interface, 7(1), 1-29.

Hutchinson, W. & Knopoff, L. (1979). The Significance of the Acoustic Component on Consonance in Western Triads. Journal of Musicological Research, 3, 5-22

Maniates, M. R. (1979). Mannerism in Italian Music and Culture, 1530-1630. The University of North Carolina Press.

Margotlorena2. (11 June 2012). Monteverdi - Pur ti miro - Elin Manahan Thomas & Robin Blaze [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/6eA7aDYflc4?t=35

McAdams, S., Goodchild, M. & Soden, K. (2022). A taxonomy of orchestral grouping effects derived from principles of auditory perception. Music Theory Online, 28(3). https://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.22.28.3/mto.22.28.3.mcadams.html

Milne, A. (2020). How a Teenage Boy Named Sporus Became Empress of Rome Under Nero’s Rule. J. Kuroski, Fact Check. All that’s Interesting [website]. https://allthatsinteresting.com/sporus

Nussbaum, M. C. (2003) Upheavals in Thought: The Intelligence of Emotions. Cambridge University Press.

Pessimisissimo. (2009/2015). “Opera Guide 5: L'incoronazione di Poppea.” in

Exotic and irrational entertainment..books, opera, Bollywood, and other indefensible obsession (blog). Retrieved from: https://exoticandirrational.blogspot.com/2009/08/opera-guide-5-lincoronazione-di-poppea.html

[1] It is widely accepted that both the music and the libretto for this opera had multiple authors and that this duet may have been composed by one of Monteverdi’s students. This was not uncommon practice in the Renaissance, as “masters” often involved students in the production of pieces.

[2] The real-life Nero is reported to have kicked the real-life Poppea and their unborn child to death not long after their marriage. He went on to marry a few more people, including one teenage boy named Sporus, who may have been a trans woman. Sporus became Empress of Rome but sadly, committed suicide shortly after ascending the throne (Milne, 2020). Being married to Nero was apparently just that bad.

[3] There is an existing version of this piece where Nerone’s part is transposed down an octave for tenor voice. This turns the semitones into sevenths but, as will be shown later, this changes everything.