Musical collaborations, timbre, and recorded sound

Musical collaborations, timbre, and recorded sound

Part One: Thoughts on recording pianists

Dialogues, with Martha de Francisco

by Viktor Lazarov and Martha de Francisco

January 1st, 2022

Una versión del artículo en español aparece en este libro (páginas 328-341):

Revista Aleph — Convergencia de Saberes

On a chilly April morning in 2018, I left home early to meet with my former professor, world renowned recording engineer Martha de Francisco, at McGill University in Montreal. At the time, I was a first-year Ph.D. student in musicology at the University of Montreal conducting an interdisciplinary research-creation project on the performance styles of the music of J.S. Bach. Prof. de Francisco had graciously accepted to provide her expertise as a blind listener to three contrasting stylistic performances of a short excerpt of Bach’s Keyboard Partita in C minor BWV 826, an important step in the qualitative phase of my research.

I first met Prof. de Francisco as a student in her seminar The Art, Study, and Practice of Listening back in 2015 when I was pursuing a Master’s degree in piano performance at the Schulich School of Music of McGill University. Her reputation as a teacher and acclaimed expert in her domain preceded her and I could not pass up the opportunity to enlist in her multidisciplinary seminar. The guest lecturers were impressive and covered topics from music performance, psychology, psychoacoustics, neuroscience, phenomenology, and other areas. Her seminar, held in the sleek and ultra-modern Elizabeth Wirth Music Building — including some of the course taking place in a vast recording and research studio two floors below ground — proved to be a turning point in my academic career. Although I didn’t realize it then, the intellectual exchange, conversations, variety of presentation topics and research brought forth by Prof. de Francisco and her guests not only broadened my mind, but also inspired me to pursue a more scholarly path in my doctoral studies, as opposed to continuing in a performance stream.

Trained as a Tonmeister in Germany, Prof. de Francisco worked for Philips Classics at the time of their transition from LP to compact disk technology and the emergence of digital recording and editing in the 1980s. During her 23-year career with the famed label, principally in her years as a staff member, 1986-2000, the list of artists with whom she recorded could truly be described as a “Who’s Who” in the classical music world. As a pianist myself, the names of Alfred Brendel, Sviatoslav Richter, Claudio Arrau, Gustav Leonhardt, and Nelson Freire, listed in her biography among many others, hung like a golden carrot in front of my eager, graduate student’s mind. Projects that included her work as an audio engineer garnered many awards from around the world, including Gramophone, Orphée d'Or de l'Académie du Disque Lyrique, German Record Critics’ awards, and Grammy and Juno awards and nominations. In 2015, Martha received the Woman of Distinction Award by the Y Foundation in Montreal.

In person, she is warm and generous, an extremely cultured and engaging conversationalist. I was thrilled when she accepted to play a part in my research and even happier when she suggested we talk about piano timbre, a topic close to her (and my own) heart. Although the pretext for the following talk was for research purposes, our conversation led us to a broader reflection on recording piano timbre and timbre in general. In this interview, Martha relates specific experiences, notably, recording and discussing timbre with Alfred Brendel, the great Austrian pianist.

Viktor Lazarov: Thank you for meeting with me today, Martha. I believe that you and I share a fascination for the sound of great pianists. Growing up, I listened to a lot of classical music recordings at home, particularly those we might call “historical” recordings (Gould, Rubinstein, Arrau, Gilels, and so on). They have certainly had a major influence on my development as a young artist and I have always wondered how these great recordings came about. If you agree, I would love to start off our conversation today by talking about your experience recording pianists while you were working for the Philips label. Specifically, out of the many great pianists with whom you collaborated over that period of time, you seemed to have had a very productive working relationship with Alfred Brendel – could you tell me more about that?

Martha de Francisco: Thanks, Viktor. Yes, I had the unique opportunity to be a recording producer for Philips Classics and Universal Music for over 20 years. My collaborations with leading soloists and conductors gave me the chance of being exposed to and learning about music from the best. But it was my work with Alfred Brendel that became central in my career as a recording professional.

Collaborating with Maestro Brendel as the exclusive producer of his Philips recordings for two decades was an enriching experience for me. I knew him as one of the great pianists of the 20th century, a formidable artist, and an eminent intellectual with various important publications on music and on other cultural topics. His recordings count among the references of much of the pianistic repertoire. Over the years, I feel privileged to have helped him produce many major works such as complete cycles of Beethoven sonatas and concertos, and various albums of Schubert, Mozart, Schumann, and Liszt. That was a fruitful collaboration of artist and record producer.

In the initial phase of our work together, Maestro Brendel and I had many conversations about sound. Digital audio technology was being introduced in the 1980s and this was calling for new ways of thinking about microphone positions and the recorded sound. We were looking to integrate into the recordings the added clarity of instrumental sound and surrounding acoustics that digital capture provided, without losing important sonic components. Mr. Brendel and I evaluated the sound of many piano recordings together in searching for the ideal sound. He showed me various recordings he liked of the pianists from the 1930s and 40s, such as Alfred Cortot, Edwin Fisher, or Wilhelm Kempff. He would say, “Listen to this beautiful sound!” and the first thing I heard was “Shhhhhhrhrhr,” [imitating the sound of white noise on old recordings] and I thought: where is this going to lead? (Laughs) You could hear the piano somewhere in the background until your mind walked through the curtain of hiss, and only after getting used to it, you were able to really make out and appreciate the warm sound of the artist. The musical quality of these vintage recordings was without doubt superb. But were the flaws in the sound of the recordings not disturbing to him?

VL: What do you think Maestro Brendel was trying to say with his comment?

MdF: I have been thinking a lot about that. Clearly, his keen musicality did not allow the technical shortcomings of the recording to cloud his judgement, and he remained focused on the musical qualities of the performance. I understand what he and many musicians who are very fond of early recordings mean: that the essential parts of the piano sound are all clearly audible. The essential sound, meaning a certain central range of frequencies that is most important to our perception of music. You would notice that even after removing tape hiss, the piano sound of those recordings lacks brightness. Recording technology was not yet able to capture and reproduce all the sonic nuance that it does today, but as long as the fundamental melodies and harmonies were there, the musical interpretation could be clearly followed. What is not captured is not essential for the listener to get a full impression of the music, that’s why the balances that are reached in those early recordings are just what is needed. As an example, precise impulse response, the brilliance of the sound at the highest frequency range or the definition of the bass are not essential elements. What is indispensable is to hear the melody clearly embedded in the harmony, which is located in the central part of the frequency spectrum; that is well captured in those early recordings. In fact, the full spectrum within the highest or lowest frequencies is not necessary for understanding the work. From psychoacoustics, we know that this central part of the spectrum is also the frequency range where human speech happens, and humans are particularly sensitive to that part of the audible spectrum. That would explain why we need melodies to be captured accurately while the extremes of the frequency spectrum are less significant.

The sonic nuances such as the tonal colours that we are able to capture in modern recording have proven important for allowing lifelike representations of the music. We just need to be vigilant about the way we balance the various components of sound in our recordings. In the acoustics of a concert hall, the inner voices get blurred, but contemporary technology and mixing practices allow us to hear everything. This insight has helped Tonmeisters shape the sound of our piano recordings with the right amount of detail and blend to allow the most musical representation of the performance.

“– One should hear the particular sound of the pianist, the timbres and balances that are recognizably his or her own. When I listen to some old recording of Cortot (Chopin 24 Preludes 1933), Edwin Fischer’s Well-Tempered Clavier or Kempff’s Decca recordings from 1950 I get this impression. They remind me of their sound which was such an essential quality and which I witnessed in many concerts. The other features: rhythm, tempo, articulation, cohesion, are easier to transmit.

– Do modern recordings have greater clarity? There is, on old recordings, often less reverberation, and yet they have a warmer sound. And there are recordings like my second set of Beethoven Sonatas where, alas, too much reverberation has been added by the sound engineer (it wasn’t Prof. de Francisco!).

– I have, in my later years, generally insisted on pianos that were not excessively bright except for the “big” concertos. Only once in my life, I used two different pianos in one concert. The somewhat unusual programme in London consisted of the Concertos Bartok I and Schoenberg, with Haydn sonatas in between.”

MdF: Another factor contributing to the unique sound quality of those vintage recordings is the sound produced by the Steinway pianos of that time, the most frequently used grand pianos for concerts and recordings. The fact that they had a very beautiful, warm quality of sound is what inspired a melodic, singing kind of playing. Nowadays, grand pianos tend to be built for the large concert halls, for having a great sound projection, and for allowing the 40th row to hear what is played. The impact of one of those wonderful old pianos would perhaps have trouble reaching the 40th row. On the other hand, it may be more difficult to obtain a beautiful, round sound on modern concert grands, which tend to be very powerful and have a clearer projection of the attacks, especially over the orchestra. These instruments are built with the aim of generating sound that will reach the back of the concert hall, rather than allowing the pianist to produce the warm and sonorous sound which characterized those early pianos and the recordings of the 1930s and 40s.

VL: Going back to what Maestro Brendel is saying, there seems to be a level of coherence in what you hear on those analog recordings: the pianists were playing in a way that was well suited to what the technology was able to capture at the time. In addition, the pianos they were playing on enabled that nuanced, soft, natural chiaroscuro type of pianistic nuance that we hear in the interpretations of Cortot or Horowitz.

MdF: Yes, that’s exactly it. I think that everything has to do with proportions and with the right balance between the voices. This is something the pianists were doing in their playing and the technology of their time was able to record that well, even if other sound nuances were not represented faithfully.

But technology has advanced in the course of the years. Modern recording systems with improved electronics allow us to capture crisper attacks and nuanced decays of the sound; they have the advantage of presenting a greater clarity, an extended frequency range, precise impulse responses, and an improved signal-to-noise ratio. While early recordings used only one microphone in front of the piano as the sole pick-up, we now use multiple microphones to obtain a realistic representation of the piano sound in its spatial surroundings, and we can count on the benefit of modern electronics. A correct placement of various microphones and the higher definition of the audio signal enables us to capture nuances of expressive playing in greater detail than was previously possible. The sophistication of the new technology as well as the accurate choices of microphone placement and mixing developed in close collaboration with the artist, led to particularly well sounding recordings that Maestro Brendel appreciated in our productions for Philips.

VL: I think this is a good moment to talk about the specific way you use microphones to capture the sound of the pianists with whom you work. One of my fondest memories from your seminar, "The Art, Study, and Practices of Listening,” was when the students got the chance to watch you in action as you recorded with another great pianist, André Laplante. I remember you explained the positioning of microphones in closer, middle, and further layers away from the piano. Then the pianist started playing and you would listen attentively in the control room, react to what you heard, and continue adjusting the microphone positions by minimal increments until you felt you were capturing the ideal sound. This whole process happened within minutes!

MdF: Indeed, that was a good example of a Tonmeister’s dynamic process to determine the recorded sound. The piano sound that we hear on a recording is a combination of the pianist’s performance, the characteristic sounds of the instrument, and the context of the space where it is recorded, to which the pianist is constantly reacting. The recording philosophy that is applied is an additional factor that contributes to the overall impression. What happens inside the piano, around the piano, and in the acoustics of the room is essential, but the technology used to record the piano, and especially the microphone choices, placement, and mixing decisions, also affect the way the piano will sound.

An example: you are recording a pianist who is giving a wonderful performance which sounds beautiful in the concert hall; if you make a recording using only the microphones that are my furthest layer, the sound will be very vague and reverberant. If that is all you capture, the audience who listens to that recording may find the sound “boring”: the lack of clarity in the sound will not allow for the details and all the different colours of the performance to shine through. On the other hand, if we were to record exclusively with microphones that are placed very close to or even inside the instrument, the opposite would be the case: the sound would be dark, harsh, almost aggressive, and there would be no blend whatsoever. The piano sound would not appear to be breathing and the performance would lose its musical qualities. Early reflections that occur in the performance space are essential for the sound and they must be included, whether naturally or with the help of artificial reverberation tools. I believe the way a piano is recorded, or any instrument or voice for that matter, will affect our perception of the artists’ sound and the musical qualities of their performance.

“Timbre differences are more evidently perceived in string or wind instruments than in the piano, since sound production is controlled in more obvious ways: by directly causing the string to vibrate, applying pressure to an embouchure using your lips, controlling the air flow, or using percussive techniques. In the case of the piano, the instrument does not change physically from one note to the next. It is therefore hard to demonstrate that, just by applying a slightly different amount of pressure on the key, two different pianists can produce an acoustically perceptual difference of timbre playing on the same piano, in the same space. ”

VL: We take all this for granted when we listen to a great recording, yet there are so many elements involved in the sound that is presented to the public! This leads me directly to the topic of piano timbre, which I also wanted to discuss with you today. As a pianist myself, I have thought a lot about timbre over the years. As an artist, I tend to think of timbre in an abstract way, often intimately related to the physical sensation of touching the keys as well as mental associations of keys and harmonies with colours.

In your seminar, I had the good fortune to listen to a presentation by Prof. Caroline Traube, who is an expert on psychoacoustics. She heads the Laboratoire de recherche sur le geste musicien at the Faculty of Music of the University of Montreal and her international research team is composed of engineers, mathematicians, specialists in biomechanics, and pianists. Much of her research consists in analyzing the piano, pianists, and timbre from an interdisciplinary perspective. In fact, she is now my Ph.D. supervisor, and I have to thank you for introducing us!

Specifically, her presentation at your seminar examined the kind of verbalizations used by musicians, from Chinese guqin players to contemporary guitarists and pianists, to describe sound. By matching the words to specific techniques of tone production, she was able to demonstrate that these verbal descriptions – each with a semantic weight linking sound or timbre to meaning – are not arbitrary but that they consistently represent specific acoustic phenomena. Her findings were corroborated in a study involving several different musicians.

However, timbre differences are more evidently perceived in string or wind instruments than in the piano, since sound production is controlled in more obvious ways: by directly causing the string to vibrate, applying pressure to an embouchure using your lips, controlling the air flow, or using percussive techniques. In the case of the piano, the instrument does not change physically from one note to the next. It is therefore hard to demonstrate that, just by applying a slightly different amount of pressure on the key, two different pianists can produce an acoustically perceptual difference of timbre playing on the same piano, in the same space.

MdF: You are absolutely right. Those timbral differences can be clearly observed in music editing. An experienced editor will have noticed that two takes with different dynamic levels will not sound well when edited together. It is not just a question of lowering the volume of the louder take to match the softer take at the edit point, because there is a clear difference in the frequency content. The louder take will appear to be brighter and fuller while the softer take will contain fewer high frequencies and it will seem duller in comparison. We are talking about small differences of a little more than one decibel. To match the different takes at the edit point, a change of level will not suffice because of the difference in the tone colour at the juncture between those takes. The high frequency content of softer playing is usually lower, so, at that point, if we’re going to edit and bring down the level of a louder take, it is going to sound wrong; it will appear to be too bright for being so soft! If you play louder, the sound becomes brighter: an addition of high frequencies in the spectrum is consistent with louder playing.

“The piano sound that we hear on a recording is a combination of the pianist’s performance, the characteristic sounds of the instrument, and the context of the space where it is recorded, to which the pianist is constantly reacting. The recording philosophy that is applied is an additional factor that contributes to the overall impression. What happens inside the piano, around the piano, and in the acoustics of the room is essential, but the technology used to record the piano, and especially the microphone choices, placement, and mixing decisions, also affect the way the piano will sound.”

VL: That is interesting to me because what you describe here corresponds to a very intent, close listening that is an important part of live performance. Like an editor or a Tonmeister, musicians must be attentive to the way sounds they produce follow each other and blend with what they have just heard. Of course, they must also anticipate and be able to produce with technical accuracy what they hear in their minds. This process of anticipation and reaction happens within a very short amount of time and is continuous in a live performance. I am curious to know how artists verbalize this phenomenon. Maybe we could talk about real life instances when you have heard pianists speak about changing timbres?

MdF: I remember Maestro Brendel saying in a master class for string quartet, but that applies equally to pianists, “This phrase is marked piano and here you change to pianissimo. Playing pianissimo is not only playing softer, but it is also changing the character of the sound that you produce, making it rounder.” To the musicians, it became clear that they needed to modify the playing by softening the attack to get the pianissimo effect and not just lowering the volume.

Most of the time, in working with artists on the production of their recordings, the communication happens without words. Verbalizing music is something that takes place mostly in pedagogical settings. In record production, we do not talk much: the musician plays, I listen, and no words are used to describe what we hear. I constantly hear pianists change timbre by adjusting the nuances of their performance, but they do not speak about these changes. A pianist reacts to the sound they hear while they are playing or from the playback, and if they are missing a certain timbral detail they adjust their performance in order to obtain the desired result. If they are looking for a different quality of sound, they simply produce it in their performance. As a recording producer you learn to operate in the rather abstract world of infinitely nuanced sounds and non-verbal communication.

In his book “Concerning the Spiritual in Art,” a work where the painter Wassily Kandinsky makes many connections between visual art and music, he writes that colour is a power which directly influences the soul. However, colour alone is not enough. The various elements that form the work of art stand in relationship to each other. They must be considered in the light of the whole; they all together serve as building material for the whole composition.

Equally in music, a great interpretation is not only about timbral differences applied to the performance. Besides timbre, other aspects like timing differences, dynamic contrasts, the energy applied to the forceful passages, the proportions within the polyphony, the balances between voices, and the relationship between passages also play significant roles in shaping a musical interpretation. How can it be that a musician is able to perform the same piece under the same conditions – perhaps during a recording of two consecutive takes – and while one take is beautiful, the next one, played only five minutes apart, is sublime? How do all the parameters of performance work together to allow this to happen? This makes me wonder whether we will ever fully explain the magic of a music performance.

End of Part One

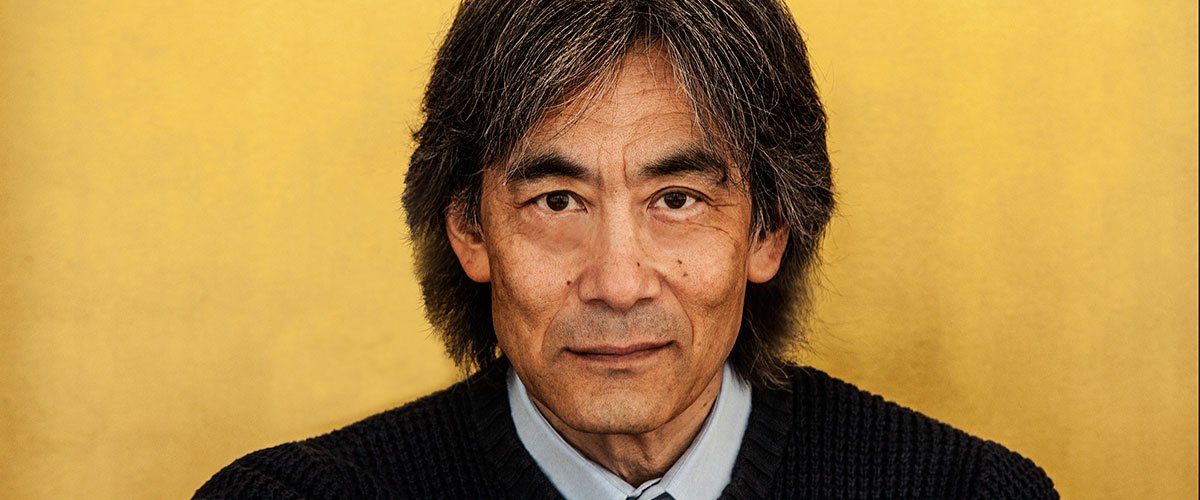

From left to right: Martha de Francisco, Volker Straus , and Alfred Brendel. London, UK, 1996.

Photo credit: Philips Classics

Suggested listening list:

Edwin Fischer, Well Tempered Clavier, Book I, Prelude and Fugue No. 16 in G minor BWV 861, J.S. Bach

Alfred Cortot, Préludes, Livre 1, La fille aux cheveux de lin, C. Debussy

Alfred Brendel, Fantasia in C minor K.396, W.A. Mozart

Alfred Brendel, Sonata in F major no.15 K.533/494, W.A. Mozart

Audio: 1. Allegro, 2. Andante Cantibile, 3. Allegretto

Alfred Brendel, Sonata No. 8 in C major, Op 13“Pathétique”, L.v. Beethoven

Link to reference recordings as complete works:

Multimedia list:

Reading list:

Brendel, A. (2015). Music, Sense and Nonsense: Collected Essays and Lectures. Biteback Publishing.

Kandinsky, W. (1947). Concerning the spiritual in art : and painting in particular 1912 (Ser. The documents of modern art, v. 5). G. Wittenborn.