Exploring the Alchemy of Orchestration: A Conversation

Roger Reynolds is Distinguished University Professor Emeritus of music composition at the University of California, San Diego. In 1989, he won the Pulitzer Prize for Music for the string orchestra composition, Whispers Out of Time. In 2016, he received the Revelle Medal from UC San Diego. His more than 150 compositions have been exclusively published by Edition Peters New York for over five decades. Several dozen CDs and DVDs of his music have been released internationally.

Stephen McAdams: What are some of the different approaches to the teaching of orchestration?

Roger Reynolds: Among composers there are at least two significant groups. One would be those who are pedagogically engaged with the actual teaching of orchestration, who really consult the books and use the examples and all the rest of that. And then there are the composers who don't feel obligated as a part of their classroom teaching to involve themselves with the particulars of an approach or a theoretical position of any sort.

The primary concepts.

Yes. I think this is an extremely important question and that is the difference between the category of people who study how something is organized and how it's done, and the category of people who are practitioners. And of course, I think there's value to be had from both groups. I practice a kind of strange straddling myself, because I think I'm thought to be somebody who is interested in structure. But in fact, the way I go about it probably is not consciously principled. I remember somebody talking to me, probably very many times and saying, “How can you have all that stuff in your mind? How does the piece of music actually get into a score? And do you know what it's going to sound like?” And what I always say is that I know what it's going to sound like, but I don't know what it's going to feel like, and that there is an experiential dimension that always is other than what the preparation that you have consciously and subconsciously made brings you to. And my aural imagination is quite strong in terms of what an instrument is going to sound like in a particular register, and how it will be different if there's several of them and so on. I think that's what you have mentioned before about the iconic profile of an instrumental timbre, even though that timbre shifts with register and so on. That's something that I think I'm pretty good at, and I'm less good at some other traditional musical skills.

What are some of the main principles that you try to communicate to students?

My teaching of orchestration is never in a classroom, but it does occur in individual instruction with composition graduate students. I guess I probably have a list of things that I look for. And when I don't find them, then I have things to say to the student about that. And these aren't necessarily in a hierarchical order, but one thing that I'm always put off by, is if the student has not recognized the essential nature of the orchestra’s choirs. That bothers me because I know that the orchestra as a social organizational entity is run according to sections, and if you want the horns to do something, you’d better talk to the first horn player, because otherwise they're not going to do it. And I've had experiences with major orchestras where it turns out to be crucial that you speak to exactly the right person, and you don't always know that that person will then act as you hope. Well they'll hear you, but they won't necessarily act on what you say. One example of this was in the Symphony [The Stages of Life] that I did for Esa-Pekka Salonen and the Los Angeles Philharmonic. In the last movement, which is about age, I wanted the string section to play sul ponticello for considerable periods of time. I mean, really an edgy, glassy sound, because that struck me as being an important aspect of aging. And so at the first rehearsal, there was no ponticello at all, even though it was in all the parts. So they are 40 or 50 people who see on their parts “ponticello,” but there's no ponticello. So at the end of the rehearsal, I talked to Esa-Pekka and I said, “You know, it's very important that we have the ponticello.” He said, “Oh. Yeah, yeah, yeah, of course. We'll talk to Glenn.” I don't know if it was Glenn, but whoever the first violin was, and we went over, we talked to him and he said, “Yes, Maestro. Yes, sir.” Next rehearsal, no ponticello. None. So it was clearly not a question of him not having understood. And so, at the end of the session, I talked a little bit to Salonen, and he just said, “I talked to him, but he says that we, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, don't sound like that.”

Are you kidding?

“And if it's tremolo and it's quiet and it's in the context of the Second Viennese school, that's fine. But otherwise, we're not going to play ponticello because that's not what we want to sound like.” End of discussion. At another time I was dealing with the American Composers Orchestra. Now this is an orchestra that was formed explicitly to play contemporary American orchestra music, and it did. It was a pickup orchestra; it didn't have a season of 40-50 concerts. It had maybe six or seven in the concert season, but they were the same people year after year. So it was an entity. And I wrote a piece, and the violins had two functions. One was the extended playing of long lines that comprised a very expressively intense component of the work. That was the voice of the piece. And the second violin section was playing very virtuosic ostinatos. They were repeated patterns, but they were difficult: they were in the high register, and they were very fast. So after the first rehearsal, the lead violin in the second section came to me, and she said “This is not a second violin part. This is the first violin part. And you’ve got to change it. You have to give this material to the first violins because this is not appropriate for us. We're seconds.” And so I talked to Dennis Russell Davies, who was the conductor, and we pulled it off. But the second violins were very irritated that they were asked to play stuff that was technically harder than what the first violins were doing, even though what the first violins were doing was musically more significant.

When I studied composition at the University of Michigan, Ross Finney, who was an accomplished orchestrator, told me that what he always told students when they were making their first forays into orchestra music was that they had to use a full, multi-staved orchestra score even while sketching. They had to be looking at the panoply of possibilities at all times. But I think the more normative approach is to do what is called a short score, where you have very clear relationships and you may make notes about double reeds, brass, strings, etc. But the evolution of the music is the evolution of a set of relationships. How these pitch and rhythmic and textural factors will actually speak through an orchestra, or a large ensemble is not pre-determined. With ensemble music, the prospects are more constrained, but with orchestra music, because the canvas is so rich and so large, with divided sections, you may have 40 staff staves, it's cumbersome. So I look for sectional usage, and if there's no sectional use, there is probably an extremely heterogeneous approach where the composer has taken individual instruments or portions of different sections and combined them into some new entity. And what the student composer does not realize is that this new entity has no standing within the orchestra, and it has no identity to the conductor. So that's something that I always say, “At some point in the piece, these sections need to speak as sections because it's part of establishing the sense in the orchestra's minds and in the minds of listeners that you actually know what this beast is and how it can be used, and you’re choosing not to do the things that are more common.

In that case it’s almost a sociology of orchestration.

Yes. There is absolutely a sociology to the orchestra, and if you don’t grasp that, you will fail. That’s for sure.

So you can do unusual things, but you have to somehow demonstrate that you know the way the normal thing works. If you really need to have those combinations.

Well, we’re straddling two things here. In the LA Philharmonic case, I was dealing with the orchestra sections in the normative way, and they weren’t subdivided into 24 separate parts and so on. But they didn’t want to make the requested sound, the quality of sound characteristics. What I’m talking about is—and this is kind of inferential—if the young composer is not using sections, then it is probable that he or she is using other kinds of units because the idea of having 80 soloists, while it does occur is, I think, pretty obviously a dumb idea because the reason for having a huge number of musicians is largely to have assertive weight and to have the potential for unusual varieties, alliances, and ultimately to have the depth of choric sonorities. But the alliances need to normally arise out of or relate to the choirs as they exist. And if you ask the woodwinds, the brass, whatever, to do something that is not normative, then you’ll probably have difficulty.

You’ll get pushback.

And as I said, sometimes it’s a question—I think that’s probably fairly unusual—but sometimes it’s a question of the tradition. For example, the idea of tremolo sul ponticello is already established because it was done by the Second Viennese school, so that’s OK, but it’s got to be pianissimo, to be in the right situation, to relate to the situation of imminent peril or something. So I’m saying that the lack of traditional choirs would suggest the presence of something else. And then the question is, what is that something else? And there are two possibilities generally. One is that everybody's a soloist. And that will definitely fail. Even for the most advanced orchestra, which is to say one that has the most congenial relationship to playing contemporary scores. Or it means that the composer is organizing the timbral or whatever registral resources in an unusual way. Now that unusual way can be fine, but it needs to be intelligently managed, and that means with some respect for the social realities and the acoustic realities that orchestras believe aligns with their sound. The Vienna Philharmonic, for example, will not play certain kinds of music. It's not appropriate to their dark, rich character.

If the arrangement of the orchestral alliances is unusual, the composer might also want to change the layout of the score to something other than the tradition, top to bottom, of the woodwinds, brass, percussion, piano, harp, and strings with a soloist just above the strings. That's an extremely dangerous thing to do because it disrupts the conductor’s immediate, thoughtless grasp of where everything is, who's doing what. I think it would probably be an interesting thing to look back at the emergence of orchestral music and see where that came about. I do know that in the late 17th century, 18th century that the orchestra’s leader, the first violin, would frequently strike the harpsichord with a rolled-up score or something. I mean, it was not until Berlioz that there was really the use of a stick and the idea of a conductor who was shaping the structure of the experience, which allowed Berlioz to change tempos and do things that had never been done before, because there was somebody at the front of the group telling them how to do it, when to do it. So I don't know whether that's a teaching, but it's an awareness that I try to confront the student with. The other thing is if you look page after page after page and everyone is always playing, that's another danger signal from my point of view, because a lot of times an inexperienced user of the orchestra will have everybody playing all the time. And of course, there were periods of time when that was not at all unusual. But we don't have very many composers now at least, who are more forward-looking or innovative, but that adhere to a Tchaikovskyan or Beethovenian model of how the orchestra should play. But even Beethoven was extremely canny about when different sectors of the orchestra would have been in play at a particular moment. It was not routine. I think the more normative approach is to do what is called a short score, where you have very clear relationships and you may make notes about double reeds, brass, strings, etc. But the evolution of the music is the evolution of a set of relationships.

One of the composition students was telling me yesterday about issues she was running into in her big piece that was played somewhere in Australia. People were saying there was too much going on at the same time.

Well, I mean too much going on can be that there's too much activity resulting in virtually no palpable sound patterns. I don't want to get sidetracked on this, but so many young composers were drawn by the idea of Stockhausen's dictum in the 50s, “Astonish me with your originality.” And of course Xenakis too. The composers of that age, of that ilk, of that generation, especially Europeans, were very much hooked into the idea of originality as a necessary characteristic of any music worth paying attention to. And what that leads to over time is that more and more young people go after what I would call fragile or unreliable sound sources, and they really love those things. But the question is, does that really constitute orchestration at all? Because firstly, they're avoiding all the primary characteristics, history, and capacity of the instrument, let alone the sections. And secondly, they're producing an outcome which is only probabilistic. They don't really know that anything is going to happen because it depends on the luck of the moment, and it depends on how many coffees they bought the players of the orchestra to talk them into being interested. And so if everybody's playing all the time, probably the material that they're playing is material that I personally would not find very musically interesting because the tradition gives you a very rousing, muscular, testosterone kind of view, except for, of course, Debussy, or people that are were more mild-mannered.

I'd also say one other thing about the situation that isn't just about orchestration in terms of large ensembles, but orchestration in the sense that you can certainly see that around 1910, when a large number of composers, in fact, virtually all composers, had been dealing with the residue of the great Romantic periods at the end of the 19th century, people were writing for gigantic orchestras. And certainly Schoenberg did that, Varèse did that, Debussy, Stravinsky, and so on. But a little after 1910, there was a kind of reversal, and you see Stravinsky writing after The Rite of Spring the Three pieces for string quartet, which are exceedingly minimalist and have nothing to do with the roars of the great ballet scores. And then he goes on and he writes L’histoire du soldat which becomes very famous, and it's an amazing, wonderful piece. But it has the characteristic that there are no family alliances; there are independent representatives of different resources. Then you see Schoenberg’s Pierrot lunaire, which is also composed at a similar time.

Example of atypically heterogeneous instrumentation.

So what we get after the First World War is this prospect of the one-of-a-kind ensemble, and it doesn't catch on immediately. But I would suppose that, to a certain degree, two factors come into play. One is that if you do have ensembles that have a reduced or slightly inadequate financial base, then you've got a problem of getting numbers, and what you may do is reduce the situation to a lone representative or a minimal number of representatives of each family. And so we have a flute and a clarinet and a bassoon and an oboe, etc. Now I find that that kind of an ensemble undercuts, I guess I can almost really say fatally, the status of harmony, because you simply can't put an oboe, bassoon, tuba, alto flute, and contrabass or a violin together, you can't put a really heterogeneous group of physical bodies or sound making entities together and get a coherent spectral map that allows the frequency content to become primary. So I think that that L’histoire du soldat and particularly Pierrot lunaire became, especially because of Schoenberg's relationship to serial techniques and so on, emblematic of an aesthetic desire. And that aesthetic desire moved the composed music away from the tradition because it was obvious that the sound quality that comes from such an ensemble is a little acidic; it doesn't meld nicely. So when you talk about meld, or blend in a psychoacoustic sense, it's rather hard to attain in the one-of-a-kind ensembles. And then obviously much later and historically you have something like the Ensemble InterContemporain, which Boulez set up as a performing entity at IRCAM. I remember talking to him about this and him saying, “It never entered my head, that this was an ensemble. It was a resource. There was a woodwind quintet, there was a brass quintet, there was a string quartet and so on. And I expected that people would draw from it to make chamber ensembles. But of course the very large number of young and less experienced composers that IRCAM commissioned all wrote for the 32-instrument ensemble. So we suddenly have a Chamber Orchestra kind of entity, which wasn't thoughtfully formed and didn't exist anywhere else. And the pieces that were written under this extraordinary, even magnificent, organization and enterprise of IRCAM couldn't travel at all. If you have an orchestra of 80 or 100 people, you don't want to play a piece for these fifty or sixty of your players out there, so the pieces don't get played.

It's too much bigger than the small ensembles. It's just the wrong size.

Yes. That's something that I think has been very important, and when I choose the instrumentation of a smaller ensemble, I'm always thinking about the possibility of the harmonic fusion and its voice can be a composite voice that comes from allying instruments. However, one would describe their character, I can easily see flutes fitting with the lower register clarinet and violas. They really work well together. And so my tendency often is to omit bassoons or oboes because they draw a distracting attention unless they're soloistic. When the Nouvel Ensemble Moderne in Montreal and the Oslo Sinfonietta commissioned this violin concerto that I wrote for Irvine Arditti, Lorraine Vaillancourt made it very, very clear that I had to use all 15 players. And so I thought, you know, if there's an oboe, it's going to get in the way of Irvine. And so I just said I'm not going to use the oboe. And she grudgingly acquiesced. At the premiere, she addressed the audience and said, “I want to be clear about this, that the composer has refused to use the oboe in this piece. And I want you to understand that I regret this very much, but this was just the way it was.” I mean, she wasn't unpleasant to me about it, but I thought this was astonishing.

That’s very interesting.

The question of why ensembles have the nature they do is an interesting one, and I think an extremely influential thing. And I think that it turns orchestration into instrumentation. And orchestration has the obligation to deal with families and with choric effects and with masses. And somehow, it's not only misaligned with history, but it's misaligned with the dynamics of the way that entity works.

So these are some of the principles you try to get across to the young composers as basic principles of orchestration, that all these issues have to be taken into account.

Yes. And here at UCSD, this is true with the La Jolla Symphony, which is essentially a community/university entity that has had different conductors over its life who have treated it in slightly different ways. There have been three conductors, and when the first conductor retired, a fund was set up to commission young composers every year. It was Thomas Nee and it’s the Nee Commission. Over the years, many of my students have been awarded that honor. We always have to talk not only about the orchestra as an entity, but about the reality of a less experienced or less expert orchestra. And for example, the great dangers that arise if you ask the leader of a section to be a soloist. Because if you ask the leader of the section to solo, you take away the individual that the section has learned to need and to submit to, and you put them in another relationship. Then the normal structure of the concertmaster and the first violin section is perturbed. He or she does the bowing, and everybody has to bow the way the concertmaster says. I think I did this once, taking the first chair players from two or three different sections and making them a little concertino group. It's not a good idea because then then section is rudderless. It's not catastrophic, but it is significant and the less the orchestra is attuned to unusual demands and challenges, the more problematic it is. And so you frequently find young composers wanting to have divisi of string sections into four parts. Well, it's just not going to work. You can ask for it, but that fourth section, I'm assuming it's the back chairs, they're going to play at half the volume that the front chairs will play at, whereas in a normal context, presumably they do assert themselves, but then they know exactly what they're doing.

Safety in numbers. That's very interesting.

Safety in numbers.

RR: How do you understand the term “blend” in musical practice more specifically with respect to orchestration?

SM: One of things I've been worried about is that we have a specific notion of blend as perceptual fusion, and I think there are a lot of ways that different musicians address this term.

RR: Maybe I would contrapose blend and balance. I was thinking the huge practical issue in all of this—putting aside the question of defensive dynamic markings—is where you write something because you expect it to counter what will otherwise happen, not because it is what you want. It's what you think you need to say in order to get what you want. So there's this weird kind of a…

Trying to second guess the interpretation of the performer in a certain sense.

Yes, right. How do you put in a score “truth”? And then how do you get the conductor to really understand what it is that you're aiming for? And how does the conductor in turn get the ensemble to believe that the things he's trying to get them to do on behalf of the composer are OK? I mean, this is complicated stuff.

It's very complicated, yes.

And I so I think when you say blend, you're going to a particular issue within a larger question of, let's say, incisiveness or immediate force or lyrical depth. There are lots of terms besides blend that you could use. And so I think either if you say balance, or if you say blend in relation to balance, you then open the discussion of what the ideals are that I sometimes find myself wanting to use in an orchestral context, and how can I describe them? And of course, we found this in the wonderful project we did together on The Angel of Death, because I even talked to you about the whole question of what I called certain textural behaviors. I made up names to give you and your colleagues something to hold on to. And probably that got me started doing this for a while, but I dropped it pretty soon, and I don't do that anymore. I have no need in interacting with myself to name things.

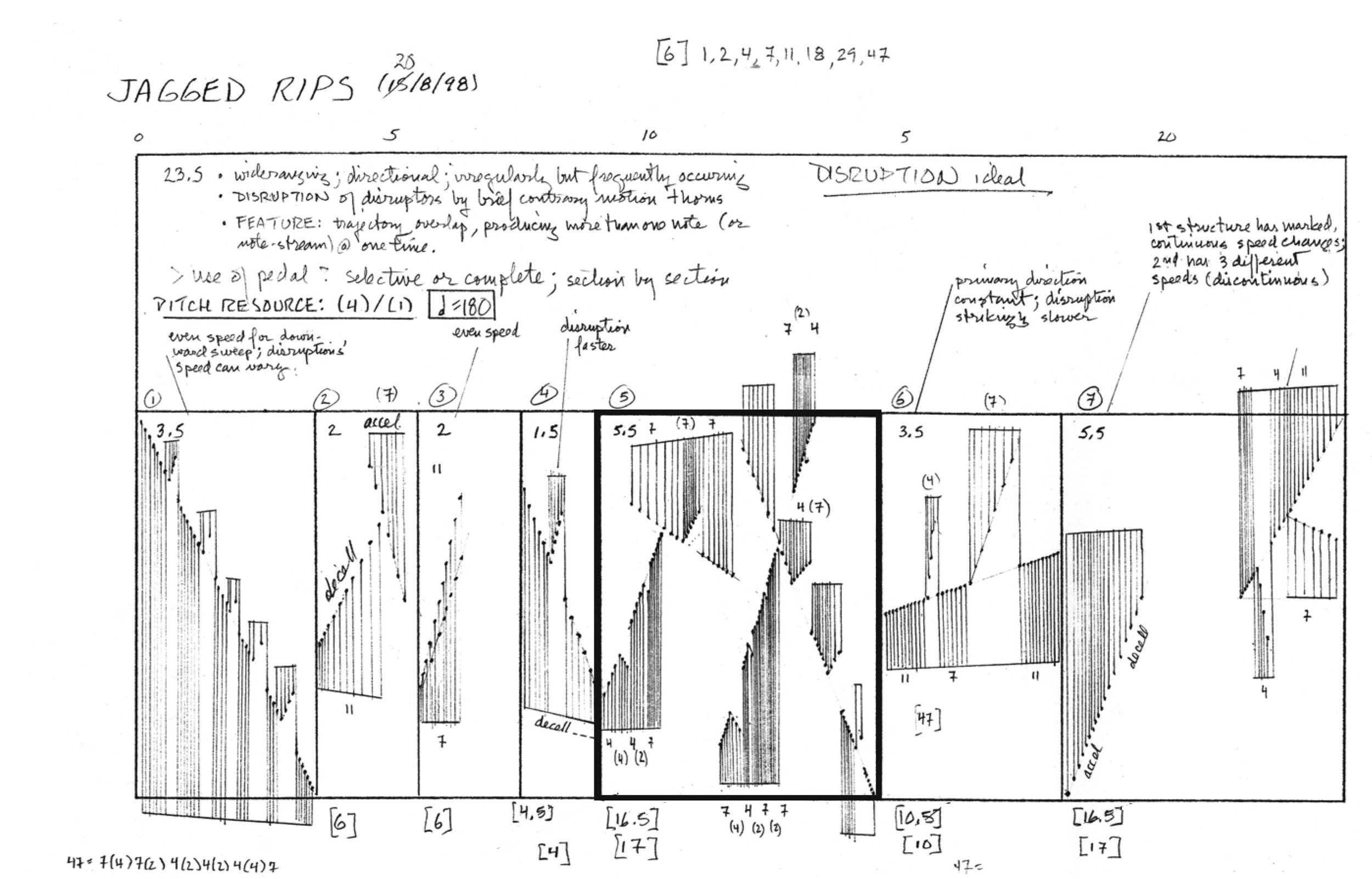

Sketch from The Angel of Death (Reynolds, 2004), showing verbal characterization of texture.

You just know what it is.

Yes. And it's not going to help my creative process to put a title on it. So maybe blend or melding or something is a phenomenon of fusion that lots of composers almost inevitably would be interested in, but I think that “balance” is better because it says I have these different things that I'm going to bring together, and I have a task for them, and this task would be optimally realized if the balances had the following character. And that's a really big issue for me because I don't believe that even in the well-intentioned circumstance of an orchestra, the primary goal of a conductor in the context of larger ensembles is not to play the piece perfectly elegantly. It's to get through it. And it's not at all uncommon that the first run-through is the dress rehearsal. Toru Takemitsu told me that he did a particular piece that involved the Nexus percussion group [From me flows what you call Time]. And there were banners that they pulled that rang bells in other parts of the hall. It was very logistically complex, and it was commissioned by the Boston Symphony and was going to be conducted by Seiji Ozawa. Toru told me that the total amount of rehearsal time he got was less than the duration of the piece.

Are you kidding?

And that in the meantime, between the rehearsal and the first performance, the orchestra did a run-out concert in New York where they played traditional repertoire.

That's surprising on the part of Ozawa.

I know, but there it is. And when he did the piano concerto for Peter Serkin riverrun, it was premiered by the English conductor Simon Rattle who was with the Berlin Philharmonic for a long time. He's a major conductor and he was conducting the LA Philharmonic and Peter Serkin was playing the piece. And after the premiere, I was talking to Toru and I said, “It's amazingly different than your other pieces. It's not lush. It's very sinuous and faint and evanescent.” He said, “Oh no, it's just they not play.” And I said, “Well, what do you mean ‘They not play?’” And he said, “Well, they didn't understand it yet. So they're just not playing.”

So some of the players were just not playing?

Yes. Or they were playing really softly. Then they did a run-out to San Diego on the following Saturday, and it sounded like Takemitsu. This is because the orchestra had gotten into it. And they thought, “OK, well, we can do this. So we’re doing it.”

So about balances, I have to say that I think balance would be better than any term or any nest of terms.

Blend would be sort of included as a possibility within balance.

If I blend these things, what I'm after is that they all sound like one. Or I blend these things, and what I'm after is that there's a bright upper edge and a dark under edge or something like that. So I think that balance would be more welcoming.

OK. The balance would also be sculpting the result of the blend in a certain sense.

Yes. We define blend as the fusion of instrumental timbres. It creates the illusion that the sound originates from single source. See, I think that as soon as you use the term segregation, you will have lost many composers, because they won't have any orientation to perception and cognition from a scientific perspective.

What would you call it? This voice operation or?

Again, I would look for a way to generalize it so that no special terminology or orientation was needed. Maybe this is too circuitous, but let's say you started out by asking the question of whether contrapuntal structures were or were not important in their work or when they were using contrapuntal structures.

How they're using timbre to clarify those.

Right. So if you're interested in contrapuntal behaviors, then by what means do you individuate or make these threads and do you wish them to be balanced close to each other? You wish them to be differentiated? If so, how do you do it?

OK, right. So it creates a continuum.

Right. Then the other thing though is, do you normally deal with a singular thread of eventuation over time? Let’s say, if you use Ives or Mahler as examples, their idea would basically be to draw people's attention, not to counterpoint—which has a traditionally very clear definition—but rather to the idea that there's more than one music happening, and that these musics need definition. One might ask the composer, “If there is more than one musical idea that has a sort of self-sufficiency to it, how would you bring them into fruitful contrast or interaction?”

OK.

But I wouldn't use any lingo because I don't think you really need it. I mean you need it in your context, but you don't need it in interfacing with composers.