Pour l’image — Philippe Hurel

EN | FR

Pour l’image

Philippe Hurel

Amazing Moments in Timbre | Timbre and Orchestration Writings

by Linglan Zhu

Published: August 2nd, 2022 | How to cite

Abstract

The opening section of the ensemble piece Pour l’image by Philippe Hurel is underpinned by a series of orchestration approaches that work in concert to generate a large-scale musical transition. The first prominent transition happens in the first 15 measures, traversing from a complex timbral agglomerate to a transparent polyphonic texture. The second transition happens in mm. 22-45 where a harmonically and timbrally dissonant texture gradually condenses into a passage of consonant chordal echoes.

Keywords: Spectral music; Philippe Hurel; Orchestration; Stream segregation; Klangfarbenmelodie

Essay

The opening section of Pour l’image (1986-1987) by the French composer Philippe Hurel is emblematic of an important formal concept for early spectral music — continuous transition that modulates the perception on a continuum. Two large-scale transitions happen consecutively within the first 60 measures of this piece, each of which showcases a set of different orchestration techniques that effectively modulate listeners’ perception.

The first 15 measures evolve around the dichotomy between a global perception of texture and a differentiated perception of lines. Under the guise of seemingly complex and diffused musical materials, the hyper-pointillistic beginning of the piece essentially shares the same basic material with the transparent four-voice polyphonic texture of the woodwind instruments from m. 12 until m. 21. Each line of the polyphony is based on a unique melodic cell, looped over and over again, and is moreover assigned a different rhythmic speed from slow (quarter note triplets by alto saxophone) to fast (sixteenth notes by flute).

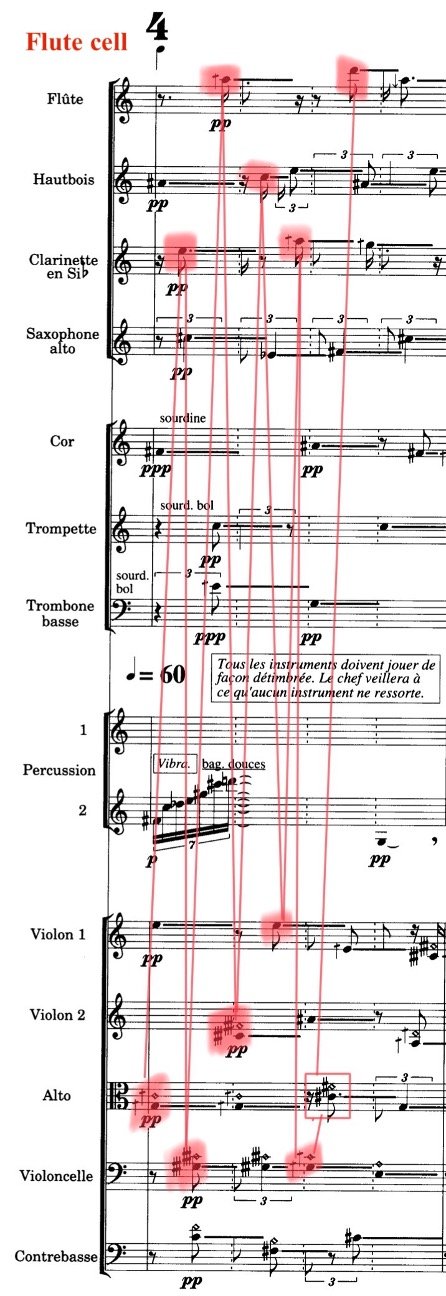

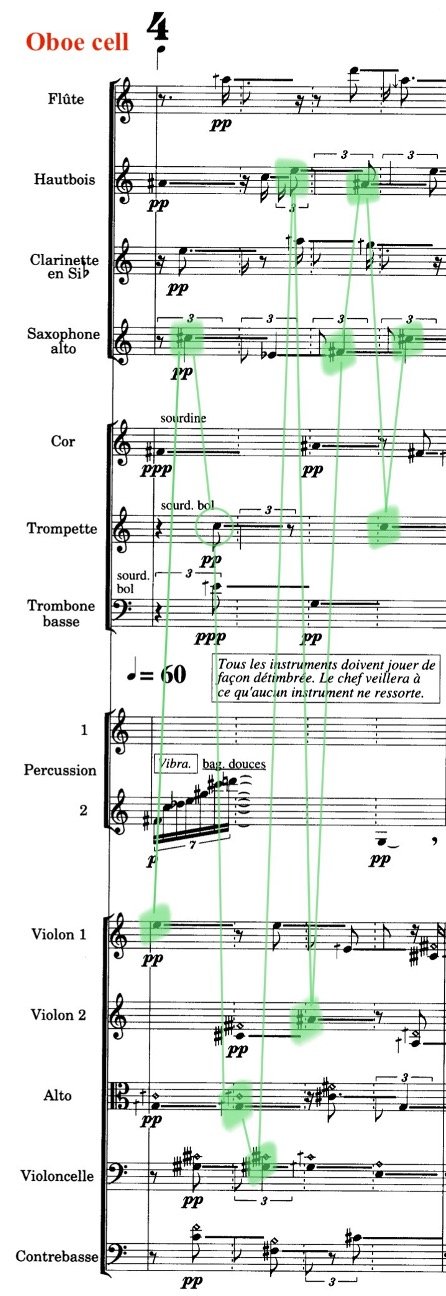

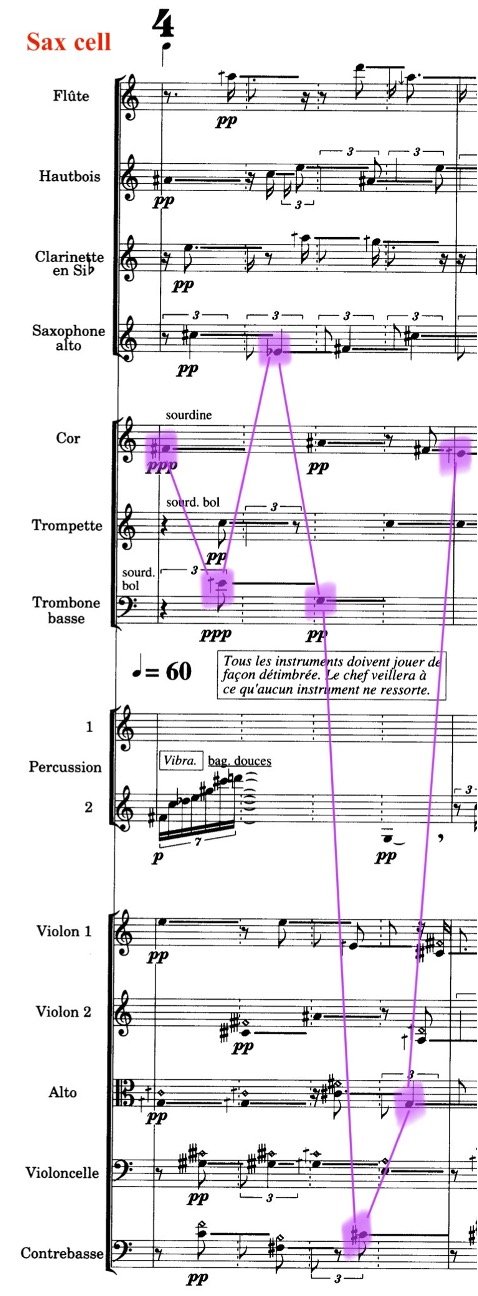

Example 1. Original forms of the four melodic cells repeated in the four-voice polyphony in mm. 12-21 in Pour l’image.

At the very beginning of the piece, these four melodic lines are imbedded in the texture with the same rhythmic proportions in terms of the note onset, only that each note of each line is assigned to a different instrument, a sharp contrast to its four-voice polyphonic arrangement as seen in mm. 15-20 where one instrument monopolizes an entire melodic line. To smear the melodic contour further, notes within these fragmented lines almost always overshoot their note values as in the original cells to different degrees, overlapping each other. This treatment adds a special aura to the overall texture, obliterating any remaining traces of the underlying melodic materials. Additionally, the original melodic cells are composed of quarter tones, whereas the four-voice polyphonic texture in mm. 15-20 only keeps their twelve-tone equal temperament approximations.

Example 2. First appearances of the four melodic cells at the beginning of the piece (m. 1). Notes are connected in order. Clarinet and saxophone cells start midway through their original forms. A few notes that don’t follow the exact pitch or rhythmic pattern as in the original cells are marked by circle (for pitch deviation; usually of a quarter tone’s difference) or square (for rhythmic deviation).

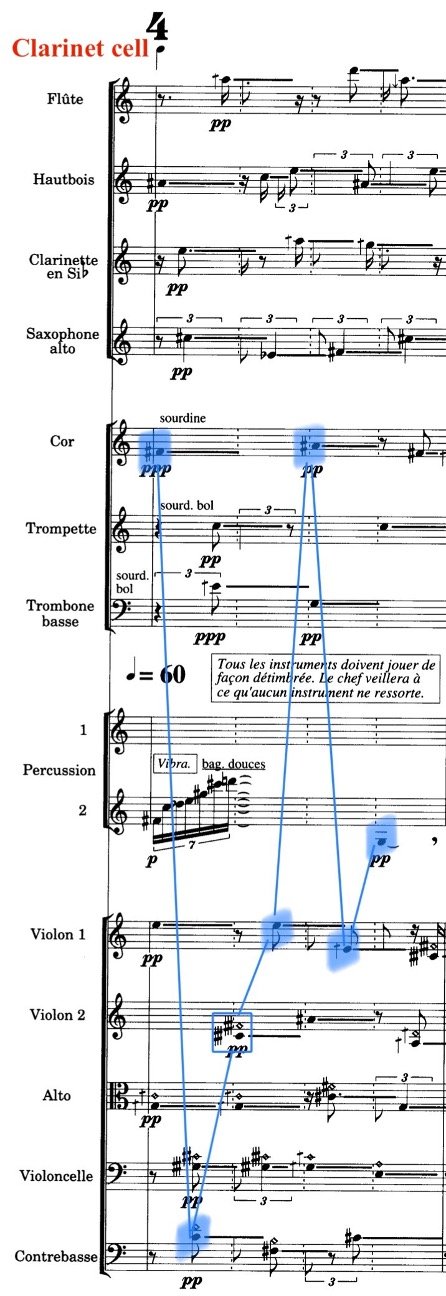

To traverse these two starkly contrasting textures, notes that belong to a specific melodic cell are gradually gathered under the same instrument by which the cell is played in the four-voice polyphonic texture, while the prolonged note values are progressively trimmed with less overlap between adjacent notes. The microtonal inflections are also one by one rounded to tempered approximations starting from m. 11. The notion of “stream segregation” (McAdams, Goodchild & Soden, in press) underlies the perceptual shift happening in this continuous transition. The beginning of the music plunges the listeners into a dense sonic amalgam where the differentiation between melodic lines is eliminated by the ever-changing instrumentation per note scattered across the entire ensemble. What remains is a shimmering texture of heterogeneous timbres which represents a global picture of the deformed four-voice polyphony. As the instrumentation becomes more and more consistent and concentrated with fewer instruments and notes gradually restore their original note values with rhythmic distinction, it is possible to gradually tell apart the shape of the individual melodic line, which attains its most clarity from m. 15 onwards as the destination of this large-scale transition. The fact that these microtonal melodic lines are progressively tempered onto 12-TET also contributes to the perceptual contrast between the two ends of this transition.

Example 3. Selected examples of how the clarinet cell is progressively orchestrated in different ways during the first transition on a per note basis.

The second large-scale transition happens between m. 22 and m. 45. The previous transition culminates with a double forte chord primarily based on the overtones of G# across the whole ensemble. Starting from m. 22, the ensemble is split into two parts (winds vs. strings) with two opposite moving bass lines: the wind instruments are supported by the bass trombone with a series of undulating pedals moving upwards with steps of quarter tone from G# to Bb (m. 44), while the strings are supported by the double bass, also with a series of pedals moving downwards microtonally from A-quarter-sharp to E. At the end, two overtone chords are formed on these two fundamentals (Bb and E) by the two groups of instruments with contrasting timbres, echoing each other with undulating dynamics. Several parallel transitions are happening during this process:

a) At the beginning, wind instruments are predominantly articulated with a rough and noisy quality, such as flutter tonguing and growling. Towards the end, the articulation gradually returns to normal for all the instruments, producing more rounded sounds concomitant with the harmonic transition to overtone chords.

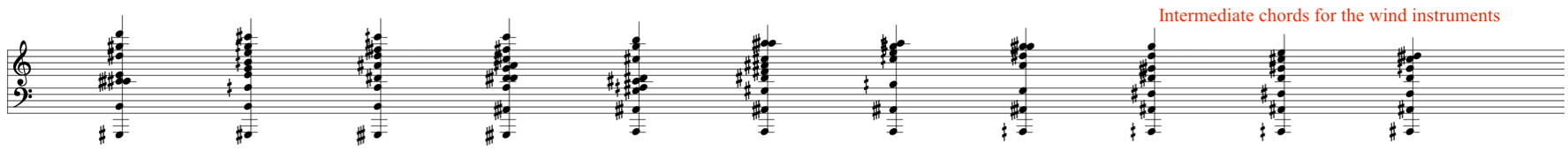

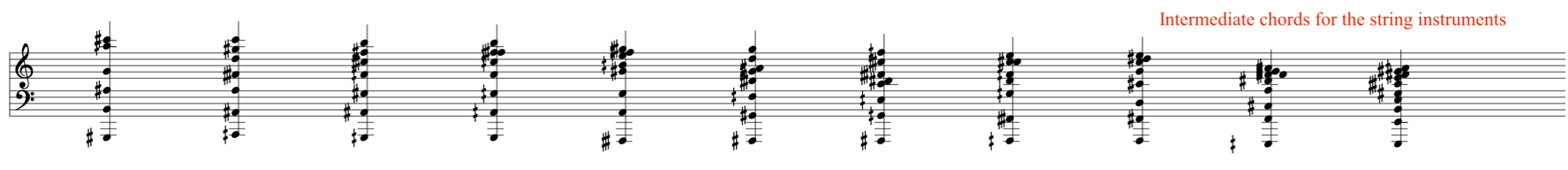

b) A series of intermediate microtonal chords are traversed by both groups of instruments, with a generally more and more compact voicing as the highest note moves downwards till reaching the ending overtone chord. These intermediate chords also interpolate the space between the dissonant starting chord and the overtone chord at the end in an audible way.

Example 4. Intermediate chords in mm. 22-45 for the two groups of instruments.

c) The intermediate chords are never voiced in synchrony until the end: at the start of this section, the entry of each note in a chord is staggered with overlaps between chords. Moreover, each note of the chord is modulated individually with a crescendo-decrescendo dynamic profile. The integrity of each chord is thus hardly perceptible. Towards the end, the entries of notes and their dynamic envelopes are gradually aligned together, giving rise to a clear transition from chaos (granularity) to order (smoothness). Furthermore, the duration and relative entries of the two series of pedals are carefully calibrated to ensure the transition of the macroscopic interaction between the two instrument groups from overlapping chordal clashes at the beginning to alternating echoes at the end. As note entries of intermediate chords are highly staggered at the beginning, in actual listening it is difficult to perceive the exact pictured transition until when chordal notes and their dynamics become more aligned with their associated pedals towards the end of the transition.

Figure 1. Dynamic evolution of the two pedal lines played by bass trombone and double bass in mm. 22-46.

Here, the gradation of harmonic roughness is coupled with the transition of articulation and temporal synchrony of individual instruments. One could envision a musical space with different sonic entities as speckles of different colors and luminance, floating around and interacting with each other, gradually coalescing into different shades of larger blotches at the end. In this sense, the title Pour l’image might be understood as an abstracted portrayal of the process of forming an image rather than a programmatic description of any specific image. This picture evokes a strong visual parallel with Paul Klee’s painting “Ancient Sound, Abstract on Black Background,” where the focus is drawn towards the juxtaposition and interpolation among colors of different hues and brightnesses. The different blotches of colors in Klee’s painting are imbued with dynamism while listening to Hurel’s piece: as if a beam of light rakes the surface, different colors are darkened and illuminated alternately.

Overall, this second transition shares the same logic with the first one structured at the beginning of the piece: from ambiguity to clarity, from chaos to order. The formal and orchestration strategy at the beginning of the piece bears a special witness to the composer’s personal languages, as it is there for the first time the composer “organized transitions between a sound fabric fusing all the melodic lines and instrumental timbres into a unique mass and polyphony permitting these lines and timbres to find their individuality.” (Lelong, 1995). The ensuing section described above focuses more on the harmonic transition. At the same time, the contrast and association between individuality and unity are also readily seen here in how the jagged chordal voices are gradually agglomerated together into a round sonic entity at the end.

Link to the piece (with score): https://youtu.be/ixnX25k3bWc

References:

Lelong, G. (1995). The Path of an œuvre (translated from French by Mary Dibbern). Booklet of the portrait album of Philippe Hurel in the compositeurs d’aujourd’hui series, Adès Record, Paris.

McAdams, S., Goodchild, M. & Soden, K. (in press). A taxonomy of orchestral grouping effects derived from principles of auditory perception. Music Theory Online.

Recording used in Audio Example 1 & 4:

Ensemble intercontemporain / Ed Spanjaard, conductor (1994-03-03)

Cover photo: Paul Klee: Ancient Sound, Abstract on Black Background (1925)