The Composite Timbre of Luigi Dallapiccola’s Vocal and Instrumental Works Since the Sex Carmina Alcei

EN | FR

The Composite Timbre of Luigi Dallapiccola’s Vocal and Instrumental Works Since the Sex Carmina Alcei

A study on writing, sound, and performance

Author

Pierre Michel - University of Strasbourg « ITI CREAA »

In the aftermath of World War Two, Luigi Dallapiccola (1904-1975) was famous for a few major works that conveyed a humanist message, particularly the Canti di Prigionia (1938-1941) and the opera Il Prigioniero (1944-1948), which rank among his better-known works to this day. The composer’s personality should, however, not be reduced to this one aspect of his output. Likewise, we should not merely see him as a practitioner of twelve-tone techniques inherited from Schoenberg and Webern, a facet that has been extensively explored by theoreticians and historians of music.

Whereas the fascinating and relevant question of rhythm in Dallapiccola’s oeuvre has been brilliantly addressed by Dietrich Kämper,[1] his music’s timbral qualities have never been examined in depth, even though they struck me as soon as I began researching it. Back then I read an article by Gérard Grisey[2] whose musical thought I found stimulating, and occasionally close to some of the Italian composer’s concerns, even though Dallapiccola’s style by no means resembles that of Grisey.

These dimensions of timbre and orchestration in general were approached until recently in terms of the ‘families’ or ‘filiations’ of musicians following in the footsteps of such luminaries as Berlioz, Debussy, Stravinsky or Schoenberg, and whose main ‘modern’ twentieth-century representatives include Berg, Webern, Varèse, Messiaen, Boulez, Stockhausen, Xenakis, Ligeti, Scelsi, Murail, Grisey, Lévinas, Dufourt, Saariaho, Harvey and many others.[3]

The question of timbre now seems to be a core concern for many composers, acousticians, musicians and musicologists, and there have been pertinent attempts to uncover historical perspectives and study with great precision the history of orchestration, the nature of ‘textures’ and their perception, as has been done in the framework of the ACTOR project (Analysis, Creation, Teaching of Orchestration).

This article synthesizes several previous publications (in several languages – see reference list) and includes new, unpublished research on Dallapiccola’s works for voice and instrumental (or orchestral) ensembles. The most relevant period for the purposes of this discussion is chiefly post-1945 (with a 1943 work exceptionally mentioned in the introduction). It bears reminding that during the 1940s, Dallapiccola, following a modal and consonant phase, shifted decisively toward an atonal language and twelve-tone technique; this language become increasingly strictly serial starting in the early 1950s.[4]

Much of his output is vocal (or choral) and his timbral work his often associated with a melodic treatment of voice. I believe it is very useful to consider a number of these pieces that combine voice or voices with instruments (without getting into opera), in an effort to carve a pathway for research on the composite timbre of vocal and instrumental works, a subject that has so far yet to be studied systematically.

I found in Alain Galliari’s research an argument that very much echoes my own research in a discussion of Webern’s Six Trakl Lieder op. 14:

“The only common feature between the instrumental writing of this op. 14 and that of the pre-war miniatures is this paradoxical sense of being in the presence of a “super-instrument”, owing to the tight texture of the polyphony and the constant crisscrossing of lines, which are conducive to a global perception to the detriment of the individualized listening to lines. This paradoxical perception is heightened by the character of the instrumental polyphony, which does not so much accompany the singing as surround it with an ever-moving sonic environment.”[5]

This study focuses primarily on vocal works, on the ‘super-instrument’ described by Galliari, with a few orchestral exceptions (as techniques are occasionally comparable). For chronological clarity, here is the list of the main works discussed below, their instrumentation and years of composition:

Sex carmina Alcaei (1943, for soprano and eleven instruments) in the Liriche greche cycle

Goethe Lieder (1953, for mezzo-soprano and three clarinets)

Cinque canti (1956, for baritone and eight instruments)

Requiescant (1957-1958, for choir and orchestra)

Dialoghi (1959-1960, for cello and orchestra)

Three Questions with Two Answers (1962-63, for orchestra)

Parole di San Paolo (1964, for middle voice and instrumental ensemble)

Sicut umbra (1970, for soprano and four instrumental groups)

Commiato (1972, for soprano and instrumental ensemble).

In this selection of works, the reader will be able to perceive an evolution in the composer’s music: in the 1940s (in this article: the Sex Carmina Alcaei) the voice largely prevails over the instruments, with a melodic, somewhat conjunct and still rather singing quality of writing despite the use of twelve-tone series: the writing is still often quite consonant. The 1950s’ works showcase an increased rigor of the serial and contrapuntal dimensions (with sometimes an intense focus on groups of two, three or four tones in the instrumental parts), a much more disjointed voice leading and an increased rhythmic complexity (the ‘floating’ rhythm famously invoked by Dallapiccola). In the latter works, the language is looser in multiple ways: the vocal techniques are more diverse (e.g., spoken word in Parole di San Paolo, mouth half-closed and ‘mormorato’ in Sicut Umbra, wordless singing in two parts of Commiato (singing on ‘Ah’), the instrumental writing is more varied, with in some cases more continuity in the musical progression and in others more sustained harmonic series with several instruments, etc.

Certainly, these works by Dallapiccola do not put him among the great innovators when it comes to the treatment of the voice itself; those are found among the next generations, beginning with Luciano Berio and Luigi Nono in Italy, Dieter Schnebel, Mauricio Kagel, Hans Werner Henze and György Ligeti in Germany, Betsy Jolas, Gilbert Amy, Maurice Ohana and Georges Aperghis in France, and George Crumb in the United States. He remained on the sidelines of these new trends, as did his German contemporary Bernd Alois Zimmermann. The singer Valérie Philippin has deftly recounted the history and evolution of these new vocal techniques in the chapter on ‘Timbre’ of her book La voix soliste contemporaine, particularly in a paragraph entitled ‘The instrumental voice, imitating instruments or electronics’.[6] While Dallapiccola did not quite partake in this turn toward new techniques, his merging of voice and instruments remains quite significant, even though it was part of a fairly traditional approach to writing (or at least, common since Schoenberg) and treatment of poetic texts as opposed to efforts to open voice to improvisation, to the body and to theater.

This article addresses different angles: I begin with a focus on counterpoint and some details of serial writing, move on to a set of remarks on the organization and perception of timbres beyond the study of combinatoriality, which brings me to some observations on timbre and form regarding a specific instrumental group; I then list a few types of textures and end with a more in-depth analysis of timbre in the first part of Commiato.

I Counterpoints, canons and timbre

The examples I have selected here are canonic contrapuntal passages: indeed, it is in such passages that Dallapiccola gave the most attention to the timbral dimension for a number of years.

I.1 Sex Carmina Alcaei

The Liriche greche cycle for female voice and various instrumental ensembles was a first step in the elaboration of Dallapiccola’s timbral work. The Sex carmina Alcaei (1943), one of the three pieces in the cycle, displays an attention to the treatment of timbre in a vocal setting that at this stage in the composer’s career remained very melodic. This work for soprano, flute, oboe, clarinet in B-flat, bassoon, trumpet, harp, piano, violin, alto and cello was dedicated to Anton Webern. While the devices it relies on are fairly simple, they are still effective and interesting. In the second part of this work (Canon perpetuus), which follows the principles of twelve-tone writing, two main elements of the counterpoint are remarkable:

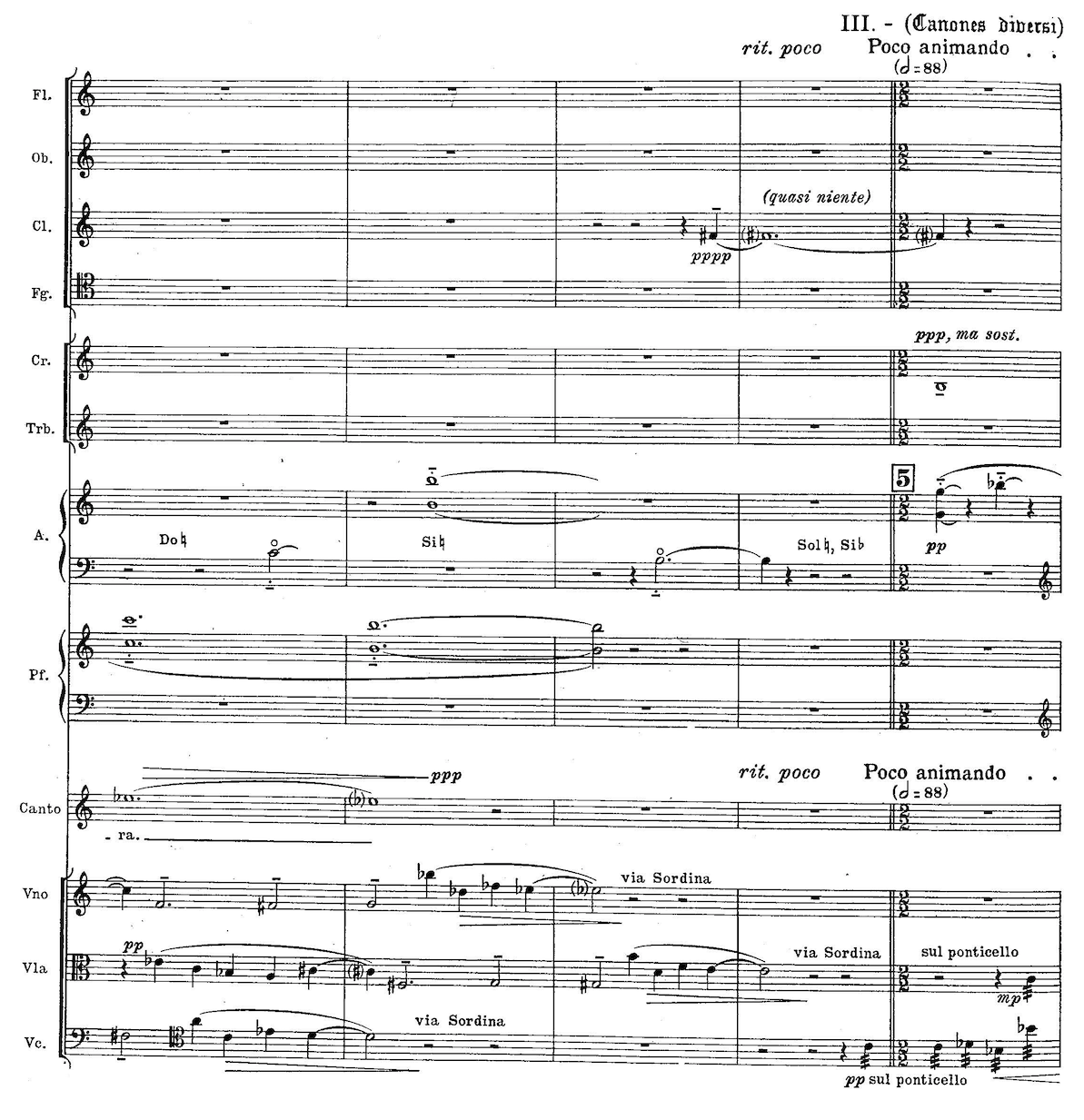

Ex. 1 Sex carmina Alcaei, Part II, pages 6, 7, 8. © Sugarmusic S.p.A. - Edizioni Suvini Zerboni, Milano (by kind permission).

I.1.1 The Cantus firmus

While this term may seem improper, it does a fairly good job of characterizing the melodic treatment in which long notes prevail (whole dotted notes or near values; tempo half=40), also fully doubled at the octave. The reversal of the original twelve-tone series (presented here by the vocal part with E as the first pitch, i.e., the minor third of the root state) is played by piano, harp, violin and viola (in harmonics), either simultaneously or alternatingly, with occasional echoes on certain notes (see the harp repeating the piano’s last four notes; number 4-5, p. 7-8 in the score).

I.1.2 The canon in three instrumental parts

This is the most perceptible feature on first listen. This canon is based on various transpositions of the original series in reversed form: first entry on D flat, second entry on D, and third on E flat. Each of these is repeated three times (in the same transposition), and a single rhythmic sequence determines the whole:

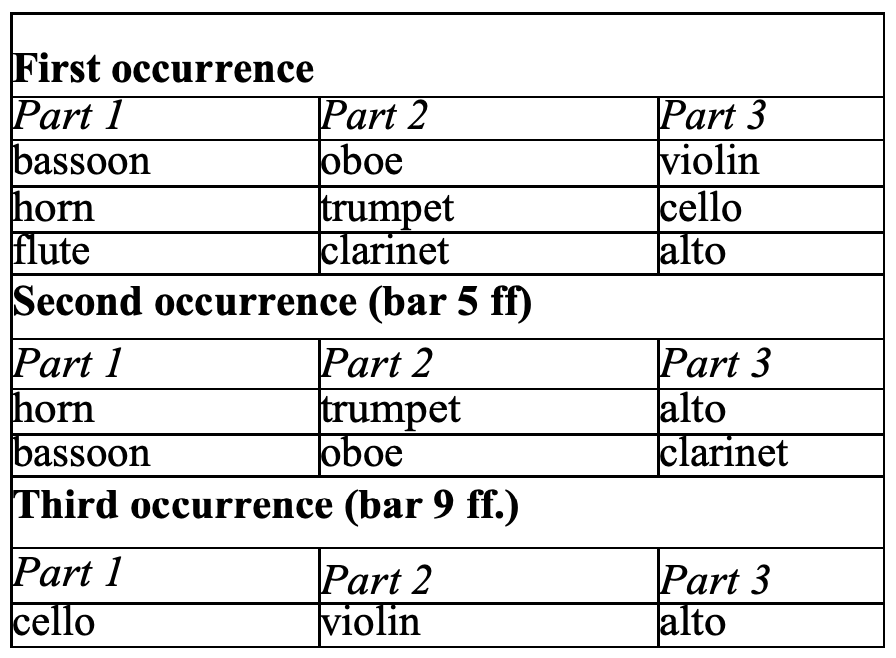

The instrumentation of this canon is as spry as that of the ‘cantus firmus’, leading to a constant renewal of the timbre and of the overall sound:

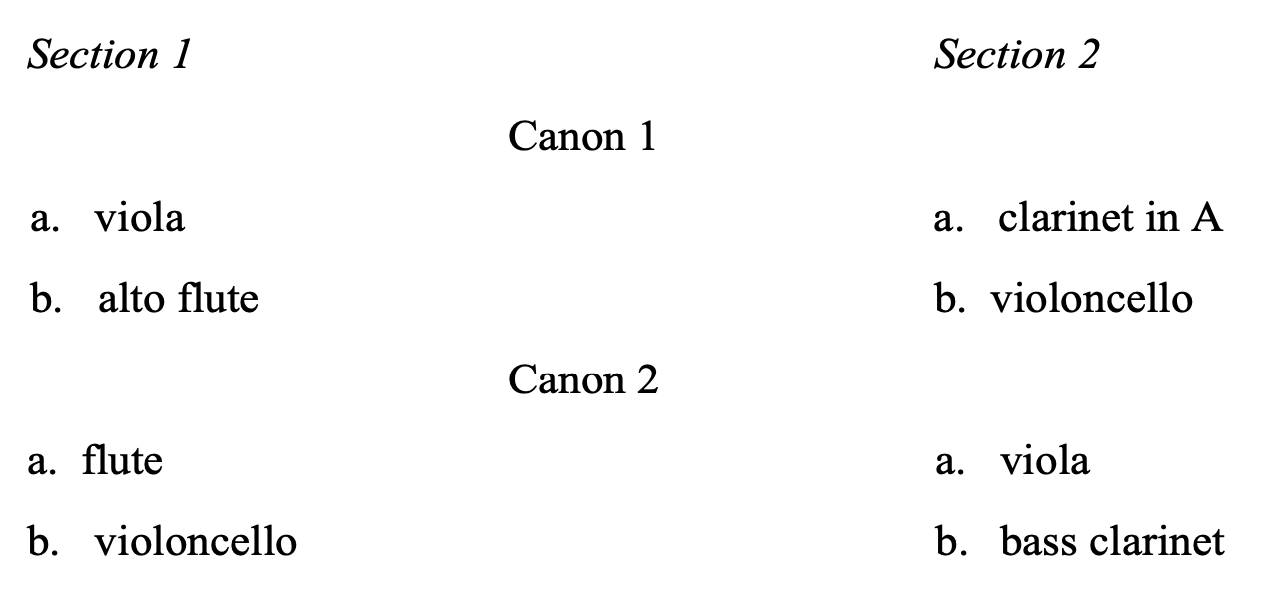

Tableau 1

Dallapiccola’s use of canon in that period is often associated, as is the case here, with the principle of Klangfarbenmelodie, and his timbral work often follows a through line which, however, changes from one work to the next, and sometimes from one part of a work to the next. This correlation between canon writing and timbre also appears in other works composed during the same period, as in the third part of the Canti di prigionia, ‘Congedo di Savonarole’ (bars 33-58, the first and fifth parts of the Cinque frammenti di Saffo, the first part of the Due liriche di Anacreonte and the second and third parts of the Tre poemi. In the piece under study here, there is an evolution toward an ever-slower renewal of the timbres, ultimately reaching stability. Indeed, the third occurrence in each part is played by only one instrument per part and only one instrumental family – the strings. This confirms the impression of timbral homogeneity already felt in the second occurrence.

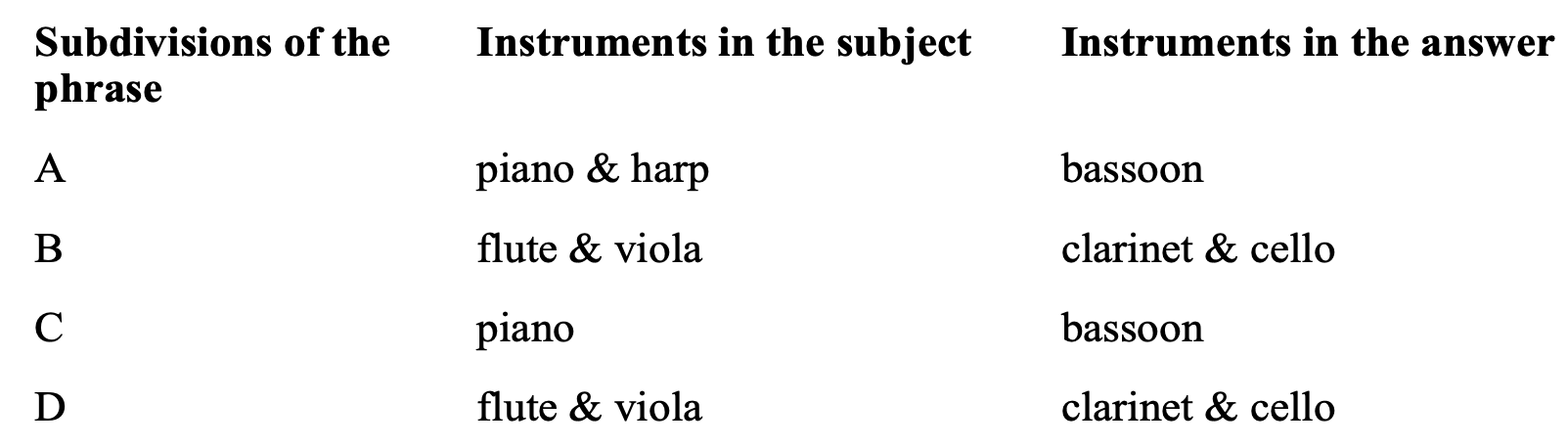

In the fifth part of the same piece (Canon duplex contrario motu), the timbral dimension is closely associated with the other dimensions of the musical writing, but in a different way: the ABA' form underlines the articulation of the timbres, which display more mobility in parts A and A' than in part B (numbers 20 to 25 in the score), during which a degree of stability sets in. Likewise, we find in the beginning of this fifth part a breakdown of subjects and answers in the canon into small timbral units; this breakdown further accentuates the renewal of the instrumental timbres within the counterpoint, a renewal that becomes increasingly fast. Upon listening to the music or reading the score for this fifth part (until the voice comes in), it clearly appears that the rhythmic scheme of this (simple) canon revolves around four timbral elements (A B C D) with specific colors:

As I have previously noted, the fairly naïve character of this research on timbre puts it at an intermediate stage of the general evolution of Dallapicolla’s language.

I.2 Cinque Canti

New elements were introduced in the 1950s, bringing us into a sometimes more austere world, in a departure from Dallapiccola’s image as a ‘Mediterranean dodecaphonist’ often conveyed by pundits and critics. On 9 March 1942, Dallapicccola met Anton Webern – a decisive encounter in many ways. He had been highly interested in the Viennese composer’s work since 1935. In 1938, he had travelled to London just to attend the premiere of Das Augenlicht. By 1943, this interest became a fascination:

‘I have chosen to dedicate to the master the Sex carmina Alcaei, which I will present to him when the war is over, with the anxiety that is well-known to anyone submitting one of their works to the judgment of a far superior individual’.[7]

In the wake, first, of his discovery of Webern’s music and then of his encounter with the composer himself, Dallapiccola pursued an increasingly rigorous writing, moving toward a sort of ‘fusion’ of the different musical parameters. A central concern in this new approach remained the contrapuntal dimension, which he explored in ever greater depth. The key component was the canon, but this technical process was sometimes stripped of its main function and merely became – as far as perception was concerned, at least – a structural device, as was often the case in Webern’s work.

It is perhaps useful to note that harmony and counterpoint were sometimes conceived almost identically in that the details of the writing are based on the initial serial model. In those cases, counterpoint merely appears as a ‘distorted image’ of harmony, which was key to the composition process.[8] This was not the only interpenetration in Dallapiccola’s post-1950 musical writing, characterized by a ‘global’ if not synthetic dimension.

While the canon is undoubtedly the foundation of counterpoint in that period of the composer’s work, it has multiple functions. Except on a few rare occasions, it is no longer treated as it used to be: the clearly canonic character of the Sex carmina Alcaei gradually disappeared from the post-1950 works. This transformation came with a change in the rhythmic writing and of the approach to twelve-tone series. It should be mentioned here that twelve-tone series are generally divided into motifs of three or four tones and that their rhythm follows proportions that are transposed from various basic units. These elements of writing are particularly visible in the passage from Requiescant I will discuss later. The frequent segmentation of the twelve-tone series, divided into groups of a few tones, yields a new type of counterpoint that can be compared to examples found in some works by Webern, such as the Symphonie op. 21 or the Concerto op. 24.

Timbre now became a key parameter among the building blocks of Dallapiccola’s changing canonic writing. The timbral interplay in a sense complemented the canon principle in the elaboration of musical structures. Below, some examples are drawn from the second of the Cinque canti to illustrate this heightened role of timbre. Two processes are specifically analyzed: the double canon with exchanges and the timbral metamorphoses between two successive canonic passages.

I.2.1 Double canon with exchanges

In a combination of two canons, each of which is associated with specific instrumental timbres, an exchange consists in replacing some notes from one canon (pitch and timbre) with notes (pitch and timbre) borrowed from the other.[9] While this device can be likened to some types of writing occasionally adopted by Schoenberg in his Variations op. 31 (in the second variation, for example), it features more systematically in Dallapiccola’s work. In the second of the Cinque canti, two canons in contrary motion are elaborated on ‘incomplete’ twelve-tone series in which certain notes from the subjects and answers of each canon are exchanged (cf. ex. 2). These ‘exchanges’ occur at junctures where a note could appear simultaneously in the subject and in its answer (for instance E followed by D between the alto and flute) and create a polarity on a unison or an octave relationship in the counterpoint.

Example 2: Cinque Canti, beginning of the second part. © Sugarmusic S.p.A. - Edizioni Suvini Zerboni, Milano (by kind permission).

In the schematic representation proposed in ex. 3, the instrumental ambitus is reduced to its most basic form. It is worth noting that in Canon 2, for the central notes (D-sharp and A-flat), there is only a transfer, not an exchange as in the other cases. On my transcription of the score (ex. 3), the notes that are subjected to an exchange of pitch and timbre are circled.

Example 3: Cinque Canti, simplified representation of the two canons at the beginning of the work.

The implementation of this device here is almost a tour de force: as the two canons are connected by a halving of rhythmic values, Dallapiccola worked on the elasticity of the rest values to have these ‘exchanges’ coincide vertically. Indeed, example 3 shows that the ‘missing’ notes are played by the other instrument, mostly at the same time as the preceding note, more rarely at the same time as the following one (see for instance, at the end of bar 3, the A of the alto played at the same time as the F-sharp of the flute). The beginning of the second part of Cinque canti is no mere writing trick; the sonic result itself deserves our attention. A subtle play on timbres develops, with the overlap of several planes putting sounds into perspective. Upon first hearing the work, the listener will first distinguish timbres by families of instruments, essentially flutes and strings – the piano and the harp come in only occasionally.

A more attentive, or ‘highly attentive’ listen, paying attention to the canon and its rhythmic construction, may reveal mixed groupings of instruments (alto-flute in G, flute-cello). The listener might also make – perhaps, in this case, with help from the score – a third type of connection (alto-flute and cello-flute in G) relying on the exchange device (see example 2) and that contradicts the previous one. This is certainly an extremely painstakingly composed timbre, whose wealth of detail is impossible to grasp for the listener.

I.2.2 Timbral metamorphoses between two successive canonic passages

The phenomenon of timbral metamorphosis will be explored by looking at this same excerpt from the second of the Cinque canti, considered as a whole (bars 1-10). This analysis will not address the vocal part, which follows other types of setting that emphasize linearity over the scattering that characterizes the instrumental material.

The comparison of the canonic episode analyzed above (bars. 1-5) with the following (bars 6-10) is particularly instructive in that these two episodes have much in common. It allows us to evidence one of the variation methods used by Dallapiccola with precision. Indeed, we find that the second section (bars. 6-10), first, borrows the structure of the preceding passage textually (except for octave or double octave transpositions) and, second, features the same order of appearance of the two canons (the first begins on A-flat-G, the second on A-sharp-B). Rhythmically, a few similarities can also be observed: the first four sounds of each part exhibit proportionally identical rhythmic schemes (with the exception of the rests).

While pitch and rhythmic expression hardly change from section to the next, we find that Dallapiccola, while retaining the strings, harp and piano, has replaced the flutes by two clarinets in the second section. By altering the timbral relationships specific to each canon from one section to the next, he fully updates the instrumental color:

These timbral changes require changes in texture in section 2. The new timbral presentation of this contrapuntal texture also entails changes regarding sound exchanges. This comparison between sections 1 and 2 shows the great precision of these timbral alterations, whose result might be compared to the visual effect produced by the rotation of a kaleidoscope.

I.3 Requiescant

The final extension of the aforementioned ‘fusion’ of musical parameters paradoxically pertains to textures that are non-canonic but imbued by the canon principle. The first bars of Requiescant (1957/1958, see Example 5; listen to the version conducted by Hermann Scherchen: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nu5goF2s_Pw) display a very complex contrapuntal structure in which pitches, registers, timbres and durations follow different types of organization. This work for mixed choir and orchestra is one of a series of choral ‘epics’ that had begun with the Canti di prigionia (1938-1941) and continued with the Canti di liberazione (1951-1955). The text for this first part of Requiescant is taken from the Gospel of Matthew (XI, 28). The other two parts were composed on texts by Oscar Wilde and James Joyce; this is Dallapiccola’s only vocal work based on English texts.

I.3.1 Pitch and register

Two twelve-tone constellations follow each other, based on a succession of eight three-tone cells, each of which feature in turn an instrumental note, a vocal note (doubled by an instrument only in the first constellation), and again an instrumental note. The furthest notes in these cells are in a minor second (or major seventh) relationship. It should also be noted that the registration of these minor seconds widens as the section progresses (from an initial major seventh to one that is doubled at the octave at the end: from G 1 to F-sharp 4:

Example 4: Requiescant, beginning of the score and schematic transcription. © Sugarmusic S.p.A. - Edizioni Suvini Zerboni, Milano (by kind permission).

I.3.2 Duration

The orchestra and choir follow two types of organization respectively:

The writing for the orchestral counterpoint combines two-note cells that stick to a proportion of 1: 2 applied to different durations. These cells are played successively by the following instruments:

oboe and clarinets (bars 1-2),

cellos and basses (bars 1-2),

contrabassoons and tubas (bars 2), etc.:

The same principle is used in the writing for the choir (bars 1-3). In each vocal section (except for the sopranos) the proportion 3: 1: 1: 2 is applied to a single repeated note (the effective durations may include a final rest). The reference values in proportion (1) are respectively the following:

alto: double-dotted quarter note

tenor: quarter note tied to a sixteenth

bass: dotted eighth

The remaining interventions of the choir do not appear to reflect such a precise organization of durations.

I.3.3 Timbres

Although they are almost constantly updated, the associations of instruments are not the result of chance. First, the composition of the instrument group that plays the first note in a cell is altered (in general reduced) by the third note (see table below). Also, constants can be observed in the instrumental doubling of the choir’s central note in the first constellation (the bassoon and the English horn appear twice each). This central note is no longer doubled by the instruments in the second constellation.

Upon more attentive examination further connections can be identified:

The instrumental groupings of the first constellation, which match the first notes of each cell, are found almost unchanged in the second constellation, but in a different order.

Table 3

From one constellation to the next, the recurrence of the minor second relationship already observed between the first and third notes is clearly reinforced by timbral callbacks that bolster the coherence of this structure. For instance, the first instrumental group in the table above (constellation I, group 1: flute, oboe and clarinet) reoccurs with slight alterations for the notes 1 and 3 in the first group of Constellation II.

I.4 Dialoghi, generalized combinatorics

Generalized serial combinatorics were a core concern for Dallapiccola in the late 1950s, as I have shown elsewhere[10] in detail regarding the second movement of his Dialoghi for cello and orchestra (1959-1960). Early into this movement (bars 57-60, pages 13-14 in the score, see Example 5), the composition with complex structures (groups of three notes transposed at different pitches and rhythmic proportions 1: 2: 1 or 1:1: 2 applied to these three-note groups) includes the orchestration as well as the other parameters.[11]

Example 5: Dialoghi, beginning of second movement. © Sugarmusic S.p.A. - Edizioni Suvini Zerboni, Milano (by kind permission).

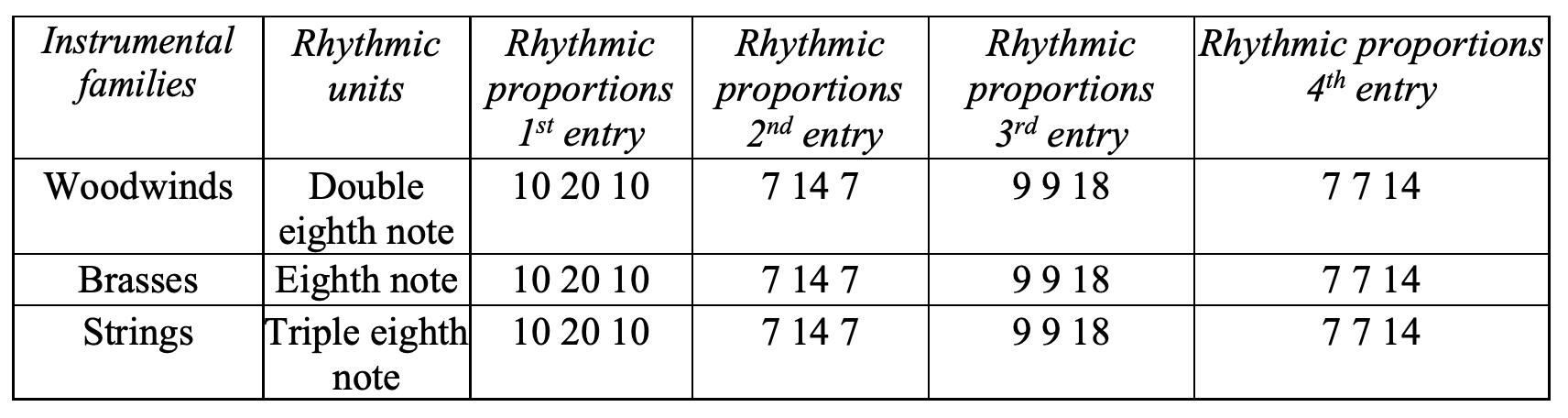

Given that each note is simultaneously played by three instruments from three different families (the group of first three notes of the twelve-tone series, E-F-D, is played/transposed on four successive degrees: C-B-G-G-sharp and in four different registers), the composer sought to avoid mere doubling and to imbue these reoccurrences with a genuine quality of sound. To that end, he gave a different weighting to each family: the strings have the shortest sustain; the woodwinds are twice as long and the brasses four times longer (see for instance the saxophone, horn and violin 2, bar 57, in Example 5). This can be summarized as follows (families are reproduced in the table based on their traditional presentation in an orchestral score):

Table 4

This indicates that although the composer pursued a complex style of writing, he always retained musical control over the structure of the parameters. The study of this passage also reveals an instrumentation that is treated as a polyphony of four groups with three instruments playing the same notes, creating well-defined timbral layers:

1 – saxophone – horn – violins 2

2 –oboe – trumpet– violins 1

3 – English horn – trombone – altos

4 – contrabassoon – tuba – basses

The connection with the instrumental groupings also pursued by Webern is evident, as is confirmed by Dallapiccola’s evocation of his 1943 encounter with Webern during which the latter told him: ‘To me now, entrusting three trumpets or four horns with a chord is unimaginable.’[12]

II Conception and perception of timbres beyond the study of combinatorics

After these basic counterpoint-related considerations which, I hope, show the degree of autonomy sometimes given to timbre in the writing (numerous other examples from the same period could support this), I believe that analysis of timbre should also encompass some less structural, rational dimensions, so to speak, but which are however very much present in latter-period works. I will now address more audible phenomena (the previous analyses are in my view unsatisfying when it comes to the perceptible reality of the work on timbres, even though they evidence an extremely elaborate degree of attention to detail), by opening a few (non-exhaustive) practical avenues into the study of various aspects of timbral writing, and especially of Dallapiccola’s timbral sensibility.

II.1 Instrumental relays

J'aimerais tout d'abord évoquer ce que l'on pourrait appeler les « relais instrumentaux« , c'est à dire l'alternance de différents timbres instrumentaux sur des éléments tenus (un son ou un accord), ou leur succession directe selon le même type d'écriture polyphonique. On remarque cette pratique dans quasiment toutes les œuvres de cette période, je n'en mentionnerai que quelques exemples.

II.1.1 Relay on a single note

In Three Questions with Two Answers (second movement, bars 35-45) an A-flat is played by the trombone, then the horn, the trumpet, etc. following a set frequency of change in timbre that equals the value of eight quarter notes except for the first sound:

Example 6: Three Questions with Two Answers, bars 35-45, pages 12 to 14. © Sugarmusic S.p.A. - Edizioni Suvini Zerboni, Milano (by kind permission).

- In Parole di San Paolo (1964)

Here, on bars 7 ff., an F is played by the clarinet, then the B flute, then the flute, the bass clarinet, etc.; the same note reoccurs much later in a very comparable setting on pages 32-35 and 40-42 of the score; in the interval, an E is also reprised from page 24 to page 28 – bars 57 and ff. – by the two clarinets in turn:

Example 7: Parole di San Paolo, page 3, bars 7 ff. © Sugarmusic S.p.A. - Edizioni Suvini Zerboni, Milano (by kind permission)

- In Commiato (end of first part and beginning of second part – bars 37-53) an A-flat is sung by the voice and reprised in turn or simultaneously by the B-flat and the E-flat clarinets; this note reoccurs at the end of the fifth part, where the voice and the instrumental ensemble create a very powerful crescendo on this A-flat, reminiscent of Berg’s work on the B at the end of Act III, Scene 2 of Wozzeck.

II.1.2 Relays by groups of instruments on several simultaneous notes

This occurs in Sicut umbra (beginning of second part): here, alternations between the strings and the clarinets are very sharp from bar 10 to bar 15 and subsequently attenuated:

Example 8: Sicut umbra, bar 10 ff. (beginning of second part, pages 5 and 6 in the score). © Sugarmusic S.p.A. - Edizioni Suvini Zerboni, Milano (by kind permission).

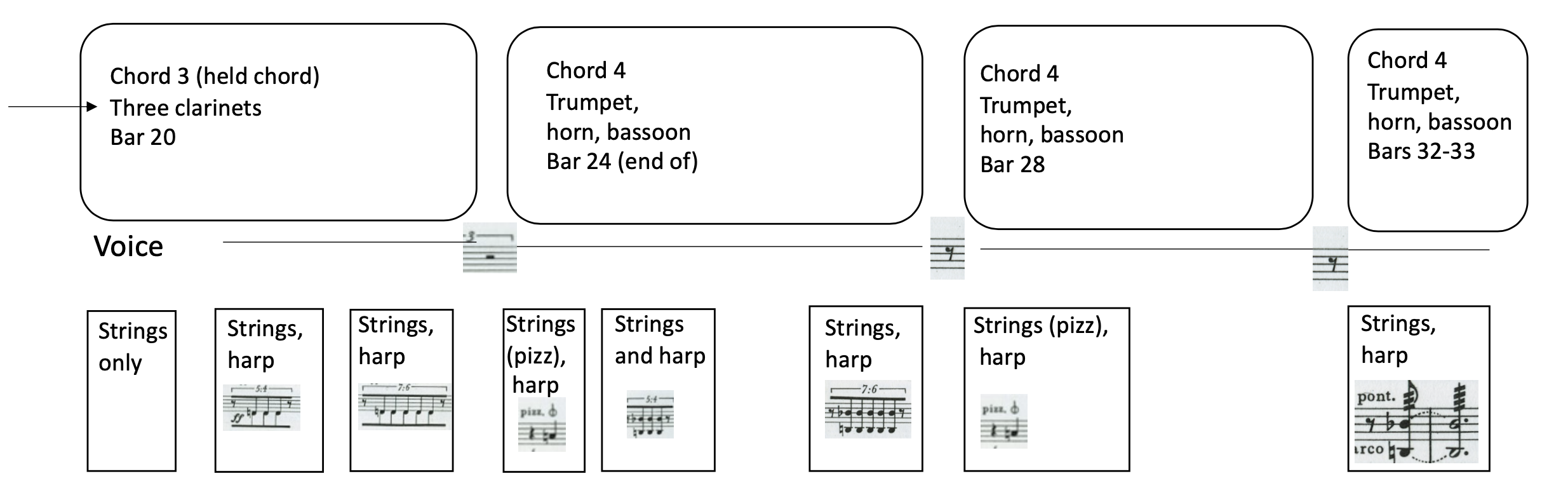

Several instances can also be found in Commiato: in the second part, on bars 53-64, where the C-sharp-G interval is held in turn by the bass clarinet/bassoon couple and by the horn/trumpet couple; in the first and fifth parts we find alternations or coincidences between chords held by the three clarinets on the one hand, and by the bassoon, the horn and the trumpet on the other (see VI).

This notion of instrumental ‘relay’, a term I am borrowing from Régis Authier’s thesis on Edgard Varèse[13] is in my view particularly important as an expressive medium in Dallapiccola’s music, and echoes some young composers’ very topical preoccupations, from the ‘spectral’ works of the 1970s such as Tristan Murail’s Mémoire-Erosion (1976), to many more recent pieces, like the beginning of O Versa for piano and twelve instruments by Icelandic composer Atli Ingólfsson (1991).[14]

II.2 Attack and resonance

This other aspect of timbral writing also echoes the approaches of musicians younger than Dallapiccola. It refers more precisely to several ways of approaching a note or chord within what can be called its ‘envelope’ (by analogy with acoustics). On several occasions, we can observe simultaneous attacks by several instruments, some of which do not sustain sounds over time: some of the instruments are used to determine a quality of the general sonic attack, whereas others also serve to provide sustain (resonance), a device also employed by Luciano Berio in O King (1968, for voice and five instruments). Moe Touizrar and Stephen McAdams have named this ‘timbral resonance’ in their examination of an ‘alternate timbral identity’ that ‘performs the function of tone prolongation and coloration’:[15] in their case study, Roger Reynolds’s The Angel of Death, this pertains more precisely to the relationship between the piano writing for two voices and the amplification/prolongation of some instruments in the orchestra. In Dallapiccola’s music, by contrast, attack and resonance are perhaps more difficult to dissociate upon listening, as attacks are generally performed by instruments that are less percussive and powerful than the piano.

In the previously cited passage from Parole di San Paolo (see Example X, page 3 of the score, bars 7 ff.), this device is visible beginning on bar 8 where the flute sustain is also initiated by the vibraphone, which, however, does not hold the note beyond a single quarter note; the same happens on the following bar between the bass clarinet and the celesta.

In Commiato (second part, bars 42 ff.) the harp and the celesta take part in the attack of the held chords by the woodwinds and the strings in a particularly interesting orchestral context:

Example 9, Commiato (part II), pages 11 and 12. © Sugarmusic S.p.A. - Edizioni Suvini Zerboni, Milano (by kind permission).

This passage shows a close relationship between harmony, rhythm and orchestration. After the first flute phrase, at the time of the first instrumental relay on the A-flat pedal (the piccolo clarinet takes over for the B-flat clarinet at the very moment when the flute phrase ends), starting at bar 41, the composer weaves a very subtle texture that is repeated at bar 45 with a few variations. It unfolds in four steps (summarized below): an introduction (string tremolos), a celesta chord, a chord played by all the instruments and held by some of them, and a motif with repeated notes on the xylorimba (with the pedal on A-flat 4 running across the entire sequence):

Flute melody (bar 40-44) with pedal: A-flat 4, then:

1- String tremolos (without contrabass, bar 42), 6 pitches

2- Same 6 pitches in vertical form (chord 1) played by the celesta (bar 42)

3 - Held chord 2 with six pitches including the A-flat of the pedal (attack including celesta and harp, end of bar 42 to 44)

4 - Rhythmic motif by the xylorimba on F (attacked 3 times, then twice, then as a single note) with various rhythms (bar 43).

We can see this succession of elements on the score (pages 11-12, Example 9), and the relations between them are very close:

The first flute phrase ends with an E which functions as a ‘pivotal note’ with the string tremolos; strings;

These string tremolos often appear after some change: after the end of the flute melody (bar 42 and 49), and after the change of instrument in the pedal part (also bar 42, then bar 45 and 49).

The harmonies of the tremolo strings are, so to speak, immediately synthesized by the celesta.

At the end of bar 42 we find a distribution of the instrumental doublings in the six-tone chord between the strings and the celesta on the one hand, and the woodwinds and the harp on the other.

The F of the xylorimba (bar 43) is also included in the held six-tone chord (played by the viola in harmonics).

All these facts contribute to give the impression of a very precise organization of the texture, with a heightened sensitivity to the questions of attack, resonance, and sound in general. This same texture reoccurs starting at bar 45, and again with a variation at the end of Part II (pages 24-25, up from bar 86), but with everything played together, and different instruments and chords (four-tone, not six).

A comparable but slightly different case can be observed in Three Questions with Two Answers (see Example 6, pages 22-24) regarding the aforementioned A-flat: here, two instruments play this sound in a complementary manner: one attacks the note ever so slightly before the other and stops a little after the other (see the cello/xylo, violin 2/celesta, then harp/violin 1 and vibraphone/cello couples); notably, in this particularly interesting passage for attacks and the internal maintain of sound (provided by the tremolos) there is – perhaps as an extension toward noise – a viola/snare drum pair on bar 40. These complementary pairs of instruments always come in slightly ahead of a change of instrument in the main thrust of the relay discussed above; to me, these pages are reminiscent of some parts of Diadèmes (1986) by Marc-André Dalbavie for viola and instrumental ensemble.[17]

II.3 Voice/instruments fusion

The relationships between vocal and instrumental timbres are also very interesting in Dallapicola’s work, as I have already shown in Part I of this article, and especially in I.3.3 regarding Requiescant. At several junctures, rapprochements or "concordances" between voice and instruments can be observed; they harken back to long-running tendencies in Dallapiccola, perceptible in particular since the Canti di Prigionia (1938-1941).

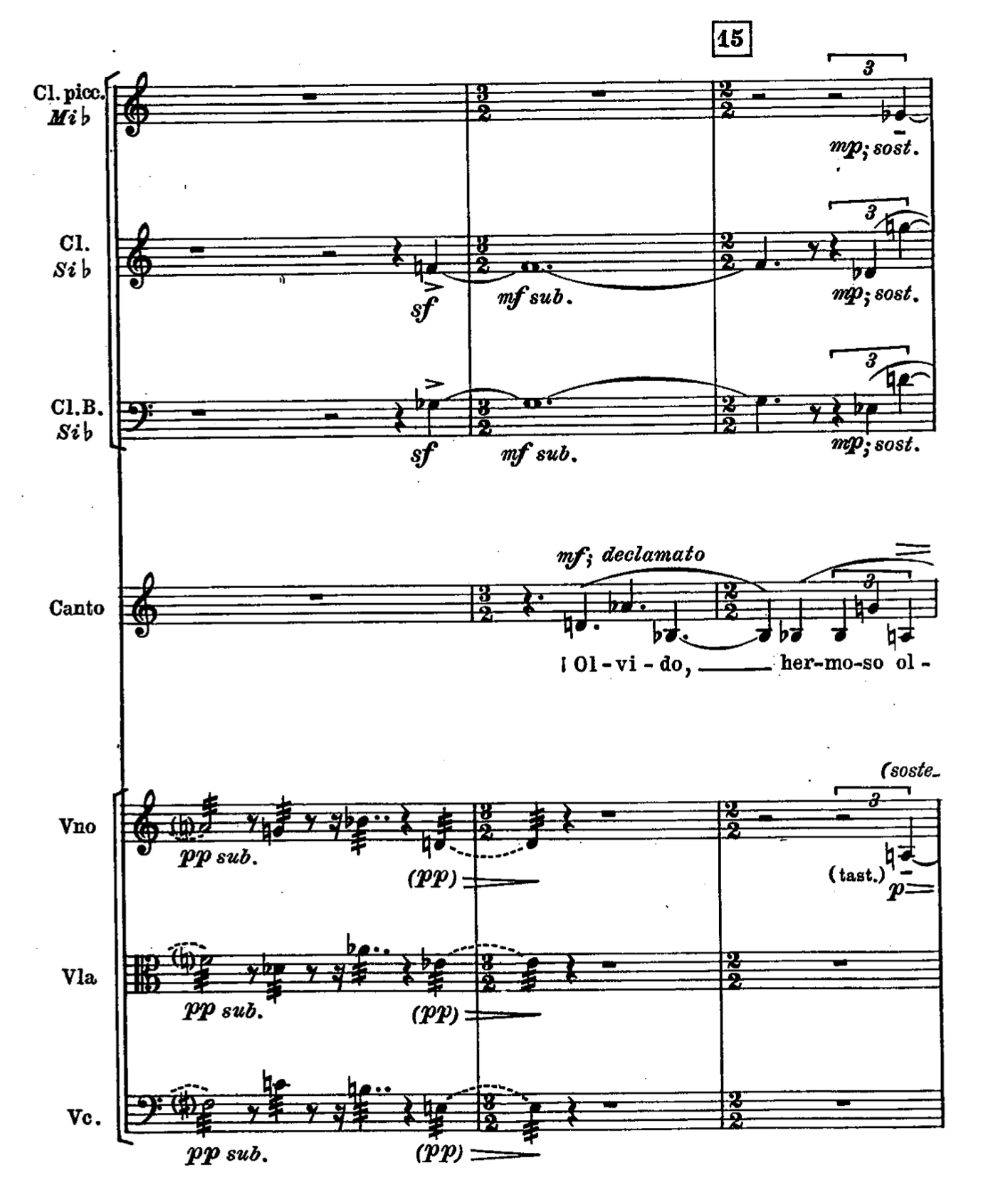

Several passages in the works feature a kind of integration of the vocal timbre in the instrumental context, both in pieces for one voice and instruments or orchestra and in pieces for choir and orchestra. On a small scale, the case of the Goethe Lieder is very representative of timbral combinations between a mezzo-soprano voice and three clarinets (respectively: piccolo E-flat clarinet, B-flat clarinet, bass clarinet). In this work with a very pronounced contrapuntal character (reminiscent of Anton Webern’s Five Canons op. 16) the voice occasionally merges very subtly with the instruments, first in that it is not necessarily above the clarinets (but often at the center of the tone), and second in moments of actual fusion, where there are no longer really any words and the composer demands singing with a half-closed mouth, as is the case here at the end of the first song:

Example 10: Goethe Lieder, end of first song (from top to bottom: voice, E-flat clarinet, B-flat clarinet, bass clarinet; all written in real sounds). © Sugarmusic S.p.A. - Edizioni Suvini Zerboni, Milano (by kind permission).

Other similar peculiarities are evidenced in Commiato in part VI of this paper.

Numerous passages in the works with choir also reflect the composer’s particular sensitivity to associations of vocal and instrumental timbres: these subtle forms of fusion bring to mind other composers who may have been influenced, such as Luigi Nono in Il Canto Sospeso (1955-56). I believe a comparative study of this piece and of the Canti di Liberazione (1951-55) would be instructive.[18]

III Timbre and form

The formal dimension of timbre or more simply of instrumental formations has often been emphasized in Dallapiccola’s work, and it is worth recalling here the symmetrical arrangement of the Goethe Lieder from this point of view (reminiscent of Webern’s Five Canons opus 16). Dallapiccola’s formal inclination toward symmetrical structures then further materialized in works such as the Concerto per la notte di Natale dell'anno 1956, where the five parts are divided between purely instrumental episodes (1, 3 and 5) and passages with voices (2 and 4), with the whole forming a symmetrical formal edifice (see also Ulisse and its two symphonic episodes respectively placed second and second-to-last).

In the Concerto per la notte di Natale dell'anno 1956, the notion of symmetry is reflected at a lower level, for instance in the third part where the first five bars are reprised in retrograde at the end with the same instruments (this echoes the third movement of Bartók’s Music for Strings Percussion and Celesta), and in the fifth part the same happens with the first thirteen bars.

Commiato also displays a symmetry of the division between vocal and instrumental passages, but with an added nuance: movements 1 and 5 only feature limited text ("Ah"), the third part has text and parts 2 and 4 are instrumental. The gradation here is finer.

Another type of timbre-related formal phenomenon manifests itself in Sicut Umbra where the density of the vocal/instrumental formation keeps increasing:

Piece 1: group 1 (flutes)

Piece 2: voice, group 2 (clarinets) and group 3 (strings)

Piece 3: voice, groups 1, 2, 3

Piece 4: voice, groups 1, 2, 3 et 4 (harp, celesta, vibraphone)

Ultimately, in Dallapiccola’s music, the ‘notion of timbre as a delineator of form’[19] is part of a broader historical lineage and a fairly complex stylistic kinship with composers such as Berg, Webern, Bartók, Varèse and Zimmermann.

IV A distinctive instrumental group

A final point deserves mentioning, regarding the structural and expressive role played by the instrumental group made up of harp, celesta and vibraphone (and in some cases piano) in works with midsize or large formations. The post-1950 treatment of these instruments in Dallapiccola’s work is almost one of his trademarks. In Parole di San Paolo and Dialoghi (1959-1960, for cello and orchestra), these instruments all but stand out as a family of their own (in the latter’s third movement, a very important role is also entrusted to the harp and the celesta alone). In Sicut umbra Dallapiccola even formed one of his four groups (according to his own stipulations in the preface to the score) with the three instruments in question; he gives them specific attention by entrusting them with the ‘solos’ in the fourth movement (a more detailed study could show the precise way in which these instruments are sometimes associated to the others; see for instance page 56 where each of them blends into a chord from another instrumental family: strings, flutes, clarinets).

A parallel for this type of instrumental grouping comes to mind in Olivier Messiaen’s Turangalîla-Symphonie (1946-1948). As Messiaen explained in his Traité de rythme, de couleur, et d’ornithologie (Tome II, éditions Leduc, 1995, p. 154): ‘The ensemble: timbres, celesta, vibraphone united with solo piano and metal percussions, stands out as a group of its own, whose sound and role are very similar to those of Balinese Gamelan. […] In the analysis of Turangalîla, every time the timbre, celesta, vibraphone and solo piano playing unite to create an analogous music, I will refer to them with only one world: gamelan.’ It is worth noting that Bernd Alois Zimmermann also favored this kind of instrumental grouping, for instance in his 1965-66 Cello Concerto ‘en forme de Pas de Trois’ (cimbalom, glass harp, harp and percussion at the end of the first movement; the same instruments with piano, solo cello, electric bass and soprano saxophone at the beginning of the fifth, entitled ‘Blues e Coda’); Henri Dutilleux also highlighted a similar instrumental group in his Violin Concerto ‘L’arbre des songes’ (1985): ‘… there is a group of instruments which forms a homogeneous block and which plays an organic role within the piece. These are members of the keyboard family: carillon, vibraphone, piano/celesta, to which are added the harp and now and then the crotales; all these instruments are treated in a percussive, “tinkling” way.’ (original English notes on the Schott ED 7434 score, 1988).

V Proposals for a textural auditive (listening) analysis »

By relating timbral qualities with other parameters of writing, we may identify distinct musical characters whose more or less contrasted succession constitutes in my view the true dialectic – the dynamic framework – of Dallapiccola’s music. To be more exact, I would say that certain musical ‘gestures’ are also recognizable by their timbral components, i.e., the dimension of their instrumental-vocal ‘colors’ defines them to a significant extent. In this sense it may be useful to evidence musical textures resulting from the combination of timbre with other components. This approach to Luigi Dallapiccola’s late works will be merely outlined here, as presenting it thoroughly (especially when it comes to defining the notion of texture in the cases under study) would be far beyond the purview of this paper. I will nevertheless give three examples of different textures with their crude characteristics (I recommend listening to these passages without looking up the score), offering potential insights into some larger-scale formal and musical articulations.

V.1 Jittery, dynamic textures (voice and ensemble with 17 instruments)

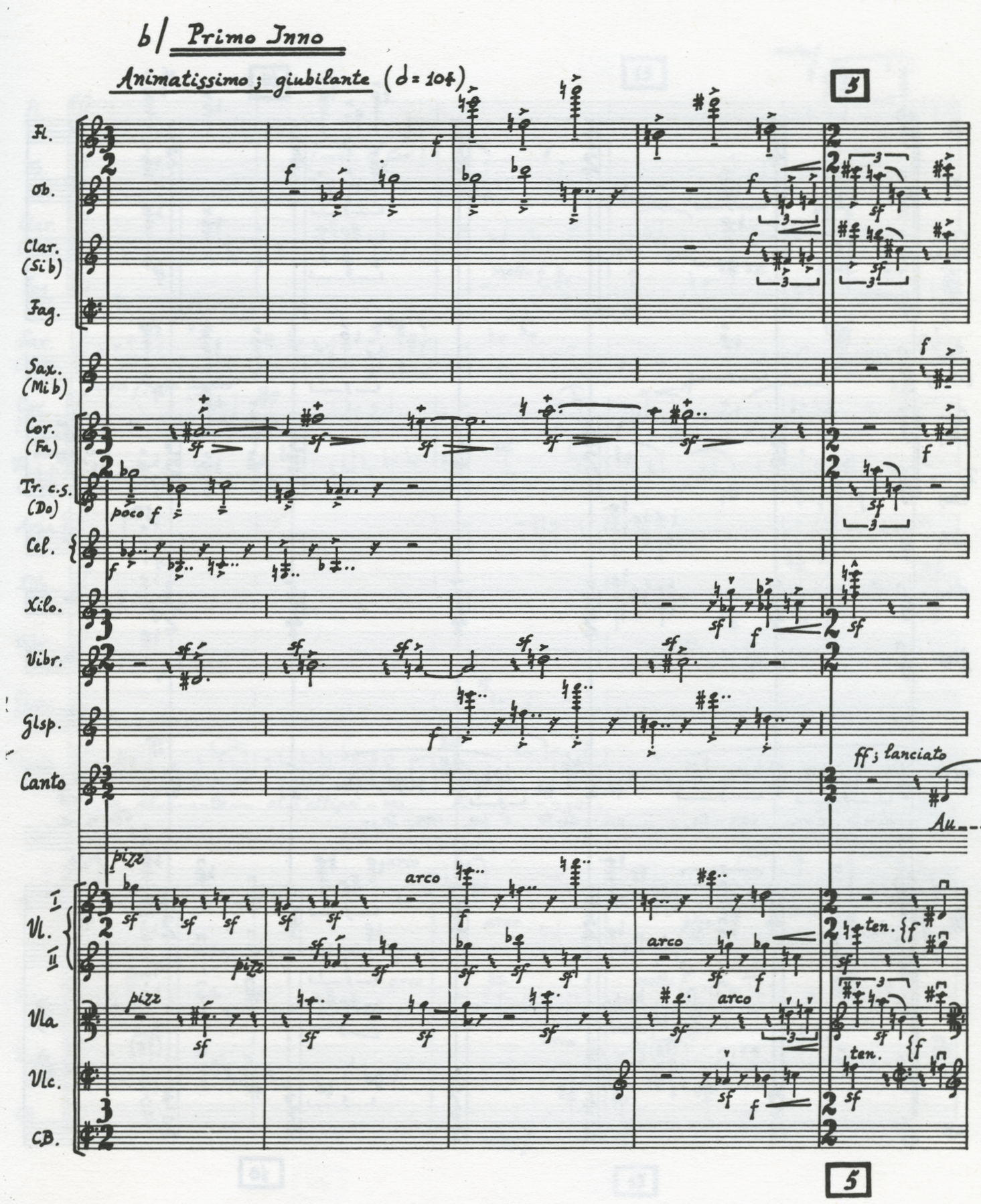

For this first type, I have picked the quasi-dramatic textures that are long-time staples of Dallapiccola’s work, found also in his operas: the second part, ‘Primo Inno’, of the Concerto per la notte di Natale dell'anno 1956, version with Valarie Lamoree, soprano; Orchestra of Our Time, direttore Joel Thome, 3’48 to 5’34) is I believe very representative for the following characteristics I would summarize as follows for the beginning:

Fast tempo and dense but timbrally discontinuous writing: the voice goes through various registers, sometimes at large intervals (from A-flat2 to C5) and with fast changing rhythms; the instruments often play highly disjointed three- to six-tone groups (formed by large intervals), spaced with rests and following often complex rhythms and frequent changes in meter; only some of the instruments follow a more linear trajectory over longer values (in the beginning: horn and vibraphone backed by viola, then trumpet at 10).

strong nuances, general indications on ‘animatissimo’; ‘giubilante’, very frequent accents, somewhat sharp-edged small melodic motives due to the relatively high registers of the wind instruments (at one point, for instance, the voice sings the deepest notes) and doublings with three-instrument groups in the more polyphonic passages (at the beginning: trumpet-celesta-violin 1).

Let us now more specifically consider the beginning of this second part (pages 9 and 10 in the score). The instrumental setting is reminiscent of Webern, albeit with a very pronounced rhythmic energy. Vigorous accents give the impression of a 3/2 time signature during the first four bars, but the richness of the counterpoint, the rhythms, the articulations and especially the orchestration is perceptible. One could genuinely speak here of timbral mixtures through the encounter and overlapping of several layers involving several instrumental groups.

Here (although this is difficult to perceive upon listening), the doublings change in an overlapping manner, as is shown by the following example:

Example 11: Concerto per la notte di Natale dell'anno 1956, second part, pages 9 and 10 in the score, wind instruments not in actual sound. © Sugarmusic S.p.A. - Edizioni Suvini Zerboni, Milano (by kind permission).

A somewhat comparable texture is perceptible in Parole di San Paolo, starting on bar 22 (page 8 in the score), from 1’39 to 2’12.

V.2 Texture with more elusive timbral characteristics (voice, three flutes, three clarinets and string trio)

For this second type, I will consider (without score examples) a textural category with a very shifting timbral definition, as it appears in the third part of Sicut umbra (bars 49-96: 3’35 to 4’40, version with Sybil Michelow, mezzosoprano, London Sinfonietta, direction Gary Bertini).

This fast-paced passage features:

quick, almost imperceptible changes of instrumental-vocal combinations through very fine-grained overlaps, with successive or superimposed neighboring colors (flutes-clarinets, then voice-flutes).

a rhythmic continuity despite complex subdivisions (5, 7) and superimpositions (7 on 2, 7 on 3, 7 on 5).

an apparently stable backdrop of strings (in the beginning especially), but widely varying in terms of modes of playing (Bartók pizzicato, regular pizzicato, arco ‘sul tasto’, ordinario playing, ‘tasto alla punta, etc.) and rhythmically irregular despite the deceiving appearance of a regular pulse.

a subtle, but non-systematic interplay of contrary movements between the voice and the instruments or between the instruments themselves.

These characteristics form an impalpable, highly fluid, almost ethereal general unity, which is disrupted after a certain point (bar 85, 4’10) by a long A-flat note (with an instrumental relay) and then echoes of sorts between certain instruments (flute-violin, bars 94-96), bringing back a more concrete, perceptible quality.

V.3 Fine-grained texture with multiple dimensions (orchestra)

This third type can be illustrated by an excerpt from the second movement of Three Questions with Two Answers (pages 12-14 in the score, from 2’55 to 3’27, version with Gianandrea Noseda directing the BBC Philharmonic), already mentioned in example 6, pages 22-24.

As we have seen, this excerpt features a single note (A-flat) that is carried over by instrumental relays and small tremolo introductions by instrumental pairs on this same note before each relay. These two very close levels are superimposed on a very soft flute melody, albeit with ever-changing rhythmic values, virtually preventing us from pinning down a pulse. I would call it an impalpable texture, whose relatively simple melodic component is highlighted in a most refined instrumental setting. The color changes are however less quick than in the previous case, and we get a sense of stability, also probably due to the constant presence of the flute.

VI Segmental grouping and instrumental harmonization: Commiato (first part)

VI.1 Musical form and harmonic/timbral profiles

In the previously cited article (note 3) by Moe Touizrar and Stephen McAdams, I have found some very promising avenues to approach some aspects of Dallapicolla’s writing, following criteria observed by the two authors in the work of Roger Reynolds, echoing arguments on timbre that have already been formulated in the general framework of the ACTOR project. I am referring in particular to the ‘timbral delineation of formal boundaries’, to the practice of ‘juxtaposing materials by using kaleidoscopic textures and gestures’,[20] and to ‘the subtly modulating instrumental harmonization of chords, with a few notes that carry over into the following chord’.[21] Here I will start from an excerpt of the first part from Commiato to evidence some of these criteria in a music where voice and instruments are closely linked (considering that in this first part, the soprano voice only sings on ‘Ah!’). Evidently, harmony and rhythm also contribute to this ‘delineation of formal boundaries’, but the timbre created by this very distinctive vocal and instrumental writing is an important component of it.

The first part of the work can be broken down roughly into three kinds of material which are relatively independent of each other:

hold (pedal) on A-flat, sung by the voice at the beginning and at the end of Part I

four chords of six (or more) tones, played like great (homorhythmic) blocks at the beginning of the piece (bars 1-6):

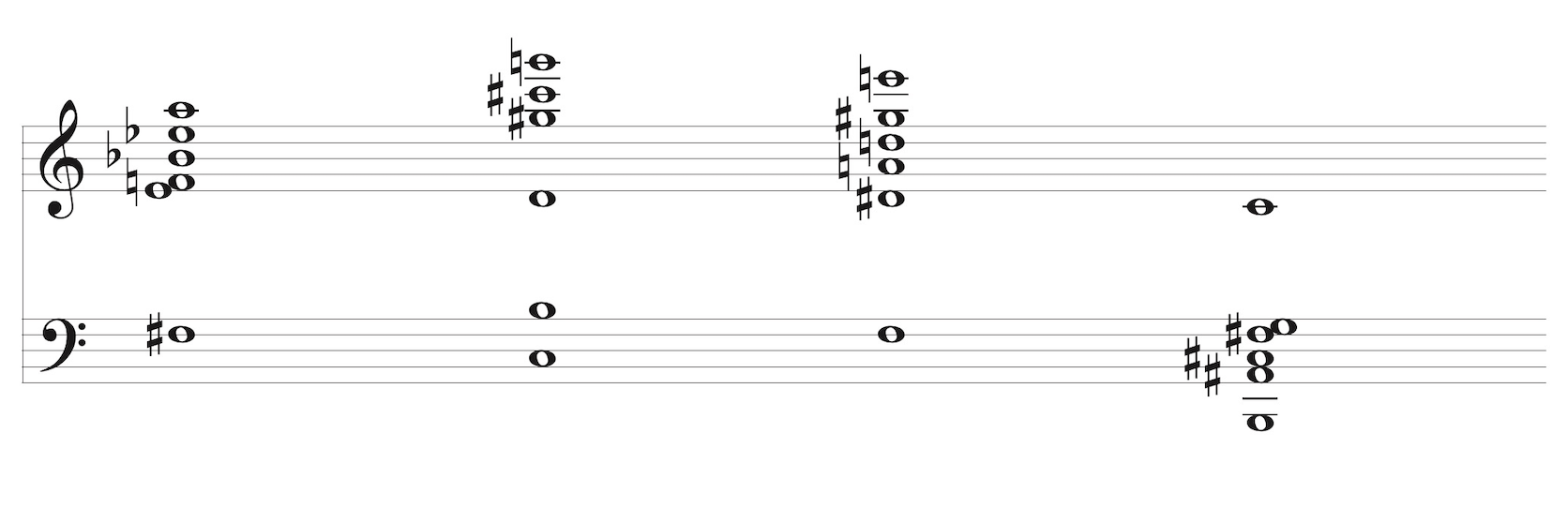

Example 12: Commiato : first chords/blocks (without rhythms).

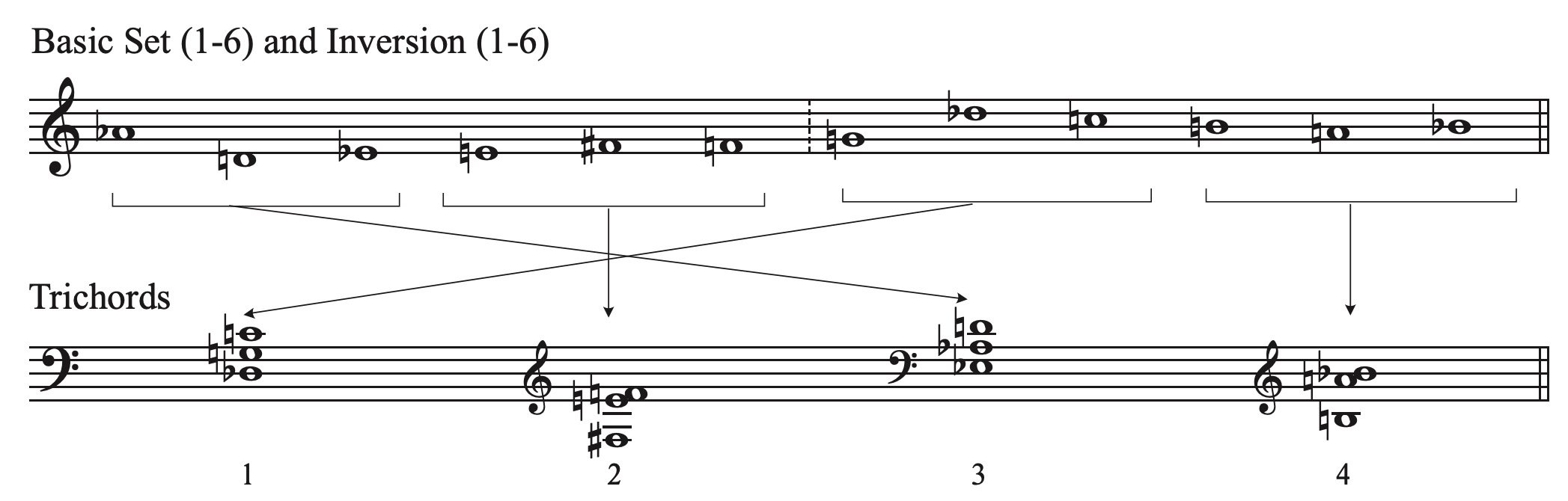

four three-tone chords presented in a more staggered fashion (with repetitions of the same chord before the presentation of the next, see bars 7 and 10) as presented here with the corresponding tone rows:

Example 13: Commiato, four three-tone chords played up from bar 6 to bar 32, with their serial origins.

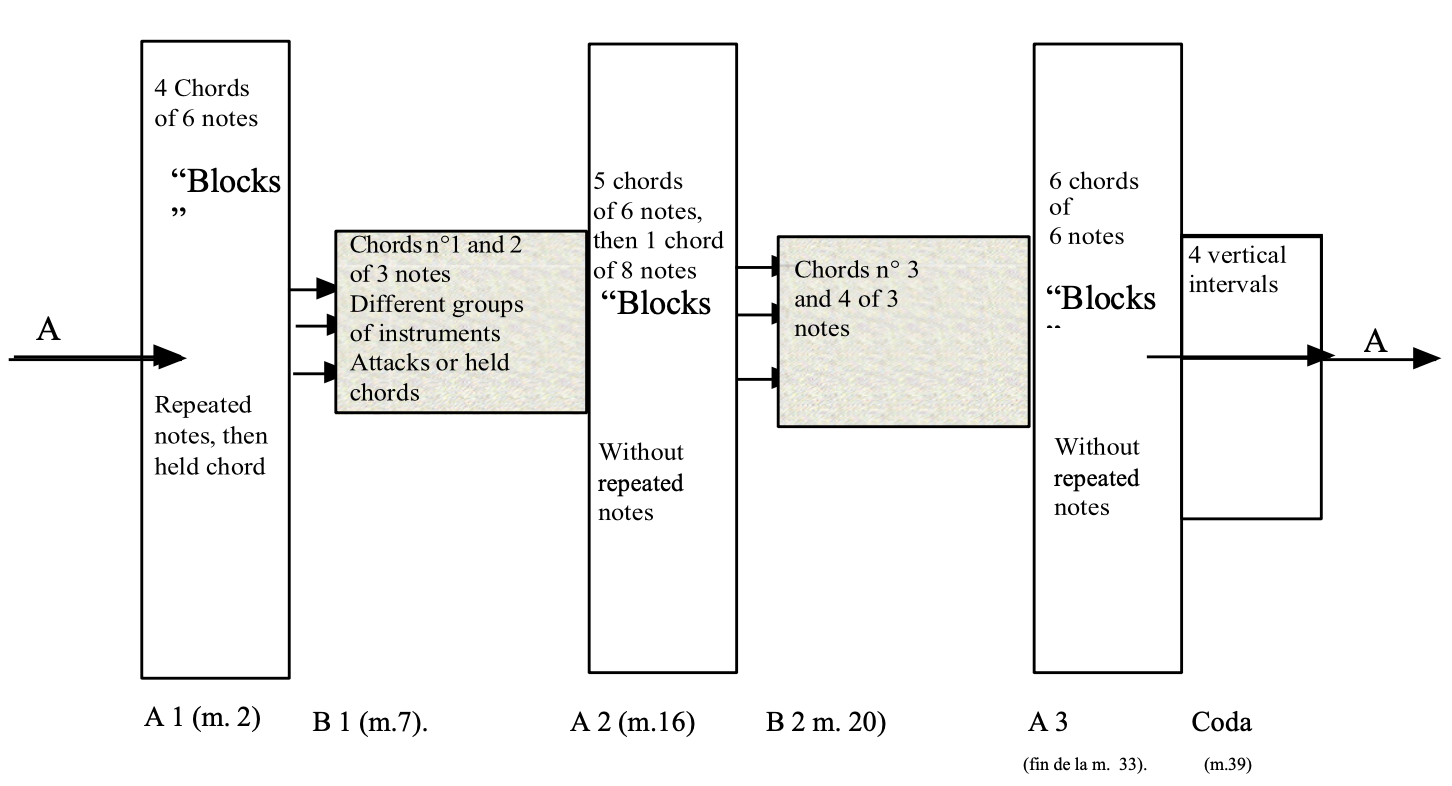

These three elements alternate in a pattern and thus create a particular sound with the voice. If we call A the ‘block’ parts of Example 12, and B the trichordal elements of Example 13, we can consider the A-parts as kinds of formal ‘pillars’: they sustain the Ab sung at the beginning and at the end of this first part (A1 and A3, see Example 14), and the A2 is, as Rosemary Brown wrote, a ‘short central instrumental interlude’.[22] That means that all vocalizing passages are sustained by the B episodes. The following diagram shows the overall shape of this first part, of which I will only discuss in detail the first parts A and B.

Example 14: Commiato (Part I): General form with internal components:

One can see here a kind of continuity between the elements: the first three-pitch chord at the end of bar 6 (three clarinets) is still comprised in the last six-pitch chord (bar 4-6). When we hear the music, it is easy to understand that the rhythmic ideas of A1 will reoccur in the vocal line, and in the B episodes for the string parts. The beginning of this part is reproduced here:

Example 15: Commiato (Part I), pages 1 to 3 of the score (clarinets are not transposed). © Sugarmusic S.p.A. - Edizioni Suvini Zerboni, Milano (by kind permission).

VI.2 The sound of the blocks (A-parts)

In A1 and A2 we see also that all notes in the chords are played both by the winds and by the string instruments, with doublings as follows for these four chords from A1 (from the lower to the higher pitches of each chord):

Example 16: Commiato, doublings for the initial chords

The distribution of the instrumental doublings in A1 is particularly interesting: as the succession of the four chords does not follow the usual criteria of tonal harmony, and as, on the contrary, both their succession and their internal structures are somewhat irregular in relation to the different registers, doublings cannot be constant for reasons due to the ranges of the respective instruments: the internal timbre of these chords is always slightly different as a result of these slightly changing doublings. The recurrence of double stops on the strings further enriches the timbre, as one of the two notes is doubled by a wind instrument and the other by another instrument. In this table, I have indicated the doublings that remain the same from one chord to the next or that recur after one or two chords, and we can see that these timbral changes are very subtle and very difficult to pin down upon listening, but that they contribute to the richness of the ensemble’s sound. We can also note on the score (Example 17 below) that the first three chords, which support the held G-sharp vocal note, are scanned in repeated short note values (5, then 3, then 2 attacks following different subdivisions each time) that are also found in the string and harp parts in B, unlike the fourth chord which is held and forms a transition with B with the three held D-flat-G-C notes on bar 6 after the other three have stopped, and picked up again at bar 7.

Also, the last chord in each four-chord group (in the A parts) introduces one or two new instruments (piano in A1, piano and xylorimba in A2). In A3 the ‘new instrument’ (xylorimba) only appears for the short conclusion with vertical intervals.

Lastly, it is worth noting that the harp is present in the B sections (with the strings), but never in the A sections; this kind of instrumental distribution is typical of Dallapiccola.

VI.3 The instrumental harmonization in the B parts

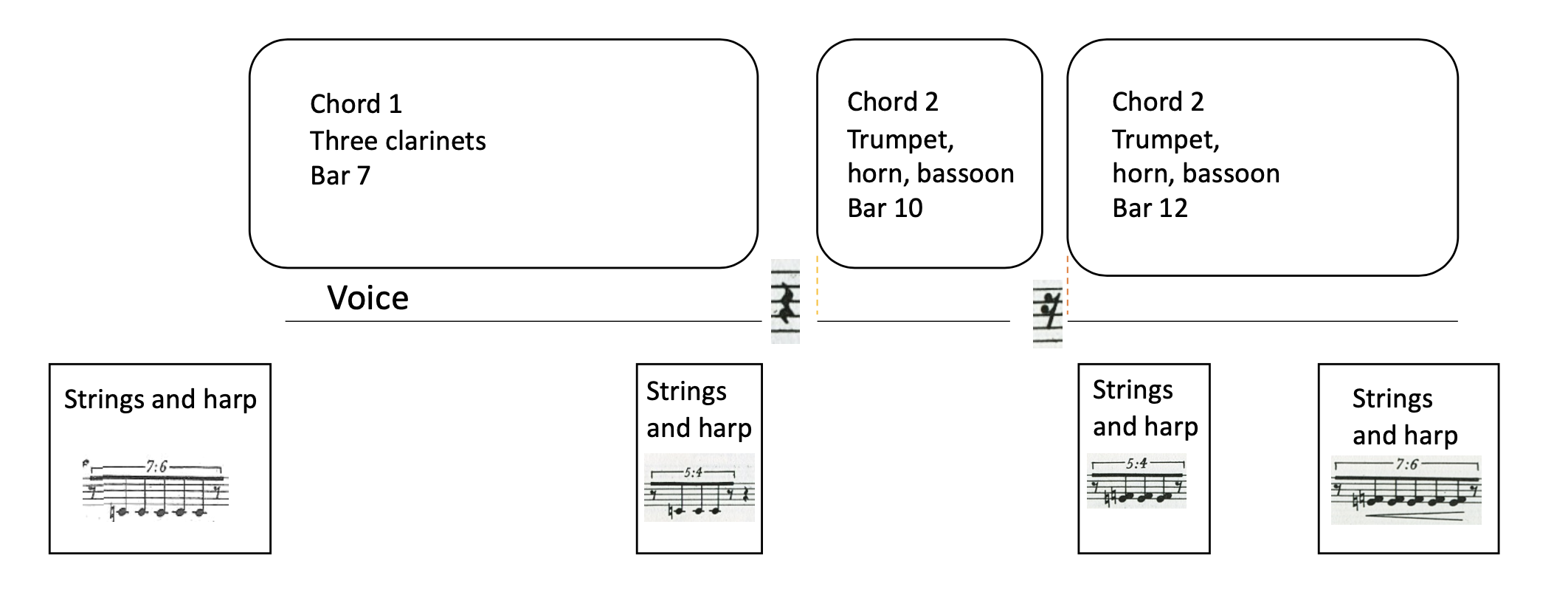

I borrow the phrase ‘instrumental voicing of the chords’ from Touirzrar and McAdams’s discussion of the Schoenbergian Klangfarbenmelodie in Reynolds’s music.[23] It is interesting here to observe all the relations between the chords and the other musical levels, and the exchanges between the instruments and the voice. Let’s quote Rosemary Brown again when she talks about B chords, which she considers to be harmonic pedals, ‘Each pedal is sustained by three wind instruments and rhythmically defined twice by interjections from the strings.’[24], as I explained before Example 13. That means that the woodwinds play held chords, as the strings with the harp play repeated notes before them and after them (the same chords repeated quickly), as we can see on page 2, bar 7 at Example 15.

We could speak here of the ‘envelope’ of these pedals, because their sound is very specific, always very close to the beginning and the end of the voice appearances (a phenomenon that is the opposite of the one described in II-2.2). The following diagram shows more precisely how the different elements are combined together in B1:

Example 17: Commiato, first part, B1 section.

The repeated string and harp notes initially operate as a signal that ‘launches’ (in 7:6) the clarinets’ chord on bar 7,[25] and then indicates the end (in 5:4) of that chord, before a brief caesura and the beginning of chord 2 (bassoon, trumpet and horn) on bar 10, where the chord is synchronized with the vocal entry (as it is later on bar 12).

In the B2-section (which begins at bar 20, see Example 18), the structure is a little different, with two short attacks (Bartók pizzicato) of the strings.

Example 18: Commiato, p. 5-6-7. © Sugarmusic S.p.A. - Edizioni Suvini Zerboni, Milano (by kind permission).

In comparing the two B sections we can easily see (and hear) in B2 that the strings’ signals are played during the held trichords of the wind instruments (and not before or after). These strings and harp interventions are different for each of the four held trichords (see Examples 17 and 19).

We see also at Example 19 here below that the composer gave special attention to the details of the instrumentation in this passage, where each sequence is separated from the next by a brief rest:

For the beginning of the held chord 3 (which comes from the long chord in A2, appearing here as a kind of resonance, hence the arrow on the diagram), only the strings are present, attacking virtually at the same time as the voice (an eighth-rest later), then joined by the harp, but with a doppia corda indication for the violin (a note played on two different strings simultaneously, which is rather interesting timbrally); in this passage the chord ends with the voice after the second signal from the strings and the harp in repeated notes.

For the first occurrence of the held chord 4 (end of bar 24: trumpet, horn and bassoon), where the voice and all the instruments are completely synchronous, the texture is slightly different: first, the strings play a Bartók pizzicato before they give the first cue in repeated 5:4 notes (a rhythm repeated twice by the vocal line a little later on short melodic sequences) and end with the cue in 7:6.

The second occurrence of chord 4, still played by the same instruments, is simpler, with just one attack (on a Bartók pizzicato by the strings) and a vocal sequence that appears to offer a slight development of the previous one.

The third occurrence of chord 4 (end of bar 32) is played by the voice and the same instruments. The strings play a ‘sul ponticello’ tremolo and the three wind instruments play sfz. All stop at the same time.

Exemple 19: Commiato, B2 Section, reduction.

Conclusion

This article has mostly discussed works for voice and instrumental ensembles or orchestra, and attempted to show that in this particular framework Dallapiccola developed a distinctive sound and a highly personal approach. The voice and the instruments form very specific textures, with or without poetic text, as we have seen. It is accordingly very important for the performers and directors to reflect on the homogeneity between voice and instruments, which is primary inherited from Schoenberg (Pierrot Lunaire) and Webern. The sound of these works is as a result very dependent on performance, as is the case for other twentieth century composers, first in terms of the vocal style of the singers (or choirs). Clearly, Dallapiccola, in these works, did not strive for a writing for accompanied melody that fit within the tradition of melody or of Lied; he drew far more from Webern when it comes to the mix between voice and instruments. In older and recent recordings of these works, quite a few singers use too much vibrato, in my view, to achieve the specific sound that Dallapiccola was looking for. Of course, this is a highly subjective matter, and some listeners will prefer the lyrical quality of some voices. I believe that the vocalists with a straighter, less vibrato-reliant approach are better suited to this type of music and blend into their instrumental or orchestral environment more effectively, as this music arguably escapes the tradition of the Italian Bel Canto. This is indeed a very sensitive question for today’s performers, and very few singers have published or recorded their thoughts on these works by Dallapiccola. This article is intended to provide input for further consideration, as I believe this music cannot be sung like Puccini or Verdi’s, even though they share a language (Italian) in common. The singer and teacher Valérie Philippin has effectively summarized post-1950 mutations in vocal music:

‘Another use of the voice, beyond the classic canons, primarily requires widening sensory references and a will to explore uncharted expressive territories.’[26] She also writes about the ‘imitation of instrumental or electronic sounds’ and ‘controlled variations in vibrato from the straightest sound to the most ample undulations’,[27] in the process also offering avenues for approaches to performing this very specific repertoire of vocal works by Dallapiccola. A few singers have made very worthwhile efforts in this regard: Valarie Lamoree in her recording of the Concerto per la notte di Natale dell'anno 1956, Cristina Zavalloni in Parole di San Paolo, Sibyl Michelow in Sicut Umbra and Dorothy Dorow dans Commiato.

Regarding the instrumental performance in this music, one additional remark should be made: the ‘old-fashioned’ vibraphone sound (with the vibrato created by the electric motor) was developed by a few great jazz players and then used for decades as muzak, and the instrument is now frequently played without this dated, if not outdated artifice. I believe, therefore, that for the purpose of balancing the very fine-grained instrumental timbres discussed in IV (celesta, harp, etc.), conductors should more often pick this straight vibraphone sound, which Dallapiccola, with his refined ear, would likely have gone for. The version of Commiato performed in Paris by the Ensemble Intercontemporain (directed by Peter Eötvös, 1981) was quite convincing in this regard, but it was not recorded.

To restore Dallapiccola’s place in twentieth-century music, we must highlight the intelligible qualities of his sound. I would mention here, as a reference to an approach that is dear to me and that did not consider music as a dead language, set in stone on a score, Pierre Boulez’s analysis in his public lectures (recorded on IRCAM/Radio-France tapes, series 3: ‘L'oeil et l'oreille’, now accessible online) of the first movement of Anton Webern’s Symphonie opus 21:[28] in addition to often painstaking serial breakdowns on which he did not dwell, he discussed phenomena that can be perceived by any listener, ‘challenges for listening’, and described timbres in the initial double canon in terms of ‘display boards and spots that light up at certain points.’ Other scholars and composers have extensively investigated timbre; I am thinking for instance of the excellent landmark volume edited by Jean-Baptiste Barrière, Le timbre, métaphore pour la composition (1991). Such an approach to the study of music is in my view necessary when it comes to Dallapiccola’s vocal and instrumental output, and I believe commenting it in terms of forms, textures and sounds, highlighting the pleasure it brings us also through timbres and orchestration is doing justice to its artistic intent. I remain persuaded that sound, the sonic, rhythmic and timbral qualities of this type of music and its performance should not be endlessly sacrificed to the benefit of the study of pitch on scores. We are now lucky to count on the international project ACTOR, which supports studies on timbre and orchestration in twentieth-century music in insightful and diverse ways; it is my hope that my contribution on Dallapiccola will prove a worthwhile addition to its resources on a composer that remains to be rediscovered.

This chapter was translated from the original French by Jean-Yves Bart, with support from the Maison Interuniversitaire des Sciences de l’Homme d’Alsace (MISHA) and the Excellence Initiative of the University of Strasbourg.

Selected references:

Writings by Dallapiccola

Luigi Dallapiccola, « Rencontre avec Anton Webern - Pages de journal », Revue Musicale Suisse, CXV/4 (1975), p. 168.

Collections of various texts

Dallapiccola on Opera – Selected Writings of Luigi Dallapiccola, translated and edited by Rudy Shackelford, London, Toccata Press, 1987;

Luigi Dallapiccola, Paroles et musique, traduit de l'italien par Jacqueline Lavaud, Paris, Minerve, 1993.

Writings on Dallapiccola

Rosemary Brown, Continuity and recurrence in the creative development of Luigi Dallapiccola, University of North Wales, Bangor, June 1977.

Angela Ida De Benedictis & Christoph Neidhöfer, « Luigi Dallapiccola, Massimo Mila, and the Journey of a Manuscript: An Analysis of Tre poemi (1949) in Context », dans Contemporary Music Review, 2017, Vol. 36, N°5, pages 440-481.

Dietrich Kämper, « Ricerca ritmica e metrica », Neue Zeitschrift für Musik,135 (1974), 94-99.

Dietrich Kämper, Gefangenschaft und Freiheit – Leben und Werk des Komponisten Luigi Dallapiccola, Cologne, Gitarre + Laute Verlag, 1984, p. 142.

David Lewin, “Serial transformation Networks in Dallapiccola’s “Simbolo”, dans David Lewin, Musical Form and Transformation: Four Analytic Essays New Haven, Connecticut, and London: Yale University Press, 1993; reprinted, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Pierre Michel, Luigi Dallapiccola, Genève, éditions « Contrechamps », 1996.

Pierre Michel, « Quelques aspects du timbre chez Luigi Dallapiccola », in Revue de Musicologie, 1992, tome 78, 1992 n°2, p. 307-330.

Pierre Michel, « Timbro, ricerca sonora e scrittura nelle ultime opere diDallapiccola (1950-70) », in Mila De Santis : Dallapiccola – Letture e prospettive – Una monografia a più voci, éd. Ricordi / LIM, collection « Le Sfere », Lucca, 1997, p. 449-466.

Pierre Michel, « Luigi Dallapiccola : Dialoghi », dans Jean-Yves Bosseur & Pierre Michel, Musiques contemporaines – Perspectives analytiques 1950-1985, Paris, Minerve, 2007, p. 41-51.

Pierre Michel, « About some harmonic and textural choices by Dallapiccola in Commiato», dans Fiamma Nicolodi, Luigi Dallapiccola nel suo Secolo – Atti del Convegno internazionale, Florence, Leo S.Olschki Editore, 2007, pages 449-466.

Hans Nathan, « Considérations sur la façon de travailler de Luigi Dallapiccola», Schweizerische Musikzeitung 115, 1975, p. 184-187.

Other writings

Julian Anderson, « Dans le contexte», Entretemps, 8, septembre 1989, p. 13-23;

Jean-Baptiste Barrière, « Écriture et modèles – Remarques croisées sur séries et spectres », Entretemps n°8, septembre 1989, p. 25-45 ;

Jean-Baptiste Barrière, Le timbre, métaphore pour la composition, éd. Christian Bourgois, 1991.

Francis Bayer, De Schönberg à Cage. Essai sur la notion d'espace sonore dans la musique contemporaine, Paris : Klincksieck, 1981, voir en particulier le chapitre VII, « La continuité spatiale», p. 122-141

Alain Galliari, Anton von Webern, Paris, Fayard, 2007.

Gérard Grisey, « Structuration des timbres dans la musique instrumentale », dans Jean-Baptiste Barrière (éditeur), Le Timbre, métaphore pour la composition, Paris, IRCAM/Christian Bourgois, 1991, p. 352-385

Harry Halbreich, « Harmonie et timbre dans la musique instrumentale », La Revue Musicale, triple numéro 391-392 Maurice Ohana - Miroirs de l'œuvre (Paris : R. Masse, 1986), 51-69;

Helmut Lachenmann, « Quatre aspects du matériau musical et de l'écoute », Musique en création (Paris : Festival d'Automne à Paris, 1989 [numéro spécial de Contrechamps, p. 105-112 ; https://books.openedition.org/contrechamps/2277?lang=fr

Michael Levinas, « Le son et la musique», Entretemps, 6 (février 1988), 27-34;

György Ligeti, « Die Komposition mit Reihen und ihre Konsequenzen bei Anton Webern», Österreichische Musikzeitschrift, 6-7 (1961), p. 297-302; traduction française de Catherine Fourcassié : « L’écriture du timbre chez Webern », dans György Ligeti, Écrits sur la musique et les musiciens, Genève, Contrechamps, 2014, p. 242-248.

Valérie Philippin, La voix soliste contemporaine – Repères, technique et répertoire, Lyon, éditions Symétrie, 2017.

Moe Touizrar et Stephen McAdams : “Aspects perceptifs de l’orchestration dans The Angel of Death de Roger Reynolds : timbre et groupement auditif », dans Lalitte Philippe, Musique et cognition – Perspectives pour l’analyse et la performance musicales, Dijon, EUD, 2019, p. 71-88. English version: “Perceptual Facets of Orchestration in The Angel of Death by Roger Reynolds: Timbre and Auditory Grouping”, Schulich School of Music, McGill University, Montréal, QC, Canada.

A journal issue : Le Timbre : forme, espace, écriture (Revue Analyse Musicale, 3 [avril 1986])

This work is supported by the lnterdisciplinary Thematic lnstitute CREAA, as part of the ITI 2021-2028 program of the Université de Strasbourg, the CNRS, and the Inserm (funded by IdEx Unistra ANR-10-IDEX-0002, and by SFRI-STRAT’US ANR-20-SFRI-0012 under the French Inverstments for the Future Program).

I Counterpoints, canons and timbre

I.1.2 The canon in three instrumental parts

I.2.1 Double canon with exchanges

I.2.2 2 Timbral metamorphoses between two successive canonic passages

I.4 Dialoghi, generalized combinatorics

II Conception and perception of timbres beyond the study of combinatorics

II.1.2 Relays by groups of instruments on several simultaneous notes

IV A distinctive instrumental group

V Proposals for a textural auditive (listening) analysis

VI Segmental grouping and instrumental harmonization: Commiato (first part)