The Most Momentous Cymbal Crash of Mahler’s 3rd Symphony

The Most Momentous Cymbal Crash of Mahler's 3rd Symphony

Amazing Moments in Timbre | Timbre and Orchestration Writings

by Emma Hill

Published: June 16, 2025

Gustav Mahler’s 3rd symphony is often considered the longest in the symphonic repertoire (Dobreff, 2024), comprising six movements and lasting approximately 100 minutes. Nick Dobreff summarized the piece as “a profound meditation on the mysteries of life and the natural world” (2024). The Finale is a peculiar movement: spanning approximately 25 minutes, it is slow, stately, and surprisingly spare in melodic material. What allows Mahler to sustain interest over such a long duration is the majesty of the principal theme and his varied use of an exceptionally large orchestra to create rich timbral contrast and build extraordinary crescendos. There are four dramatic crescendos within the Finale, each beginning from the softest possible dynamic and slowly building to an exhilarating climax (Beginning-Rehearsal 20, 21-24, 25-30, 31-End). In this essay, we will explore the buildup to the penultimate climax, which culminates in one of the most momentous cymbal crashes in symphonic literature.

At 18:28 in this recording (see Video Excerpt 1), a melody appears in three trumpets and the first trombone. As the final echo of the opening theme, it signals the approaching end of the piece. Although the dynamic is marked triple-piano, the irrepressible bite of their sound makes the quartet of brass instruments project sonorously against a soft, shimmering backdrop of tremolo strings. As they complete the first phrase, they are joined by more brass—including the remaining trombones—for the second phrase (19:49 of Video Excerpt 1), boosting the warmth and volume of the section with their added harmonic depth.

Video Excerpt 1 (18:28-20:28): https://youtu.be/bKCn1fJlPfE?t=1108

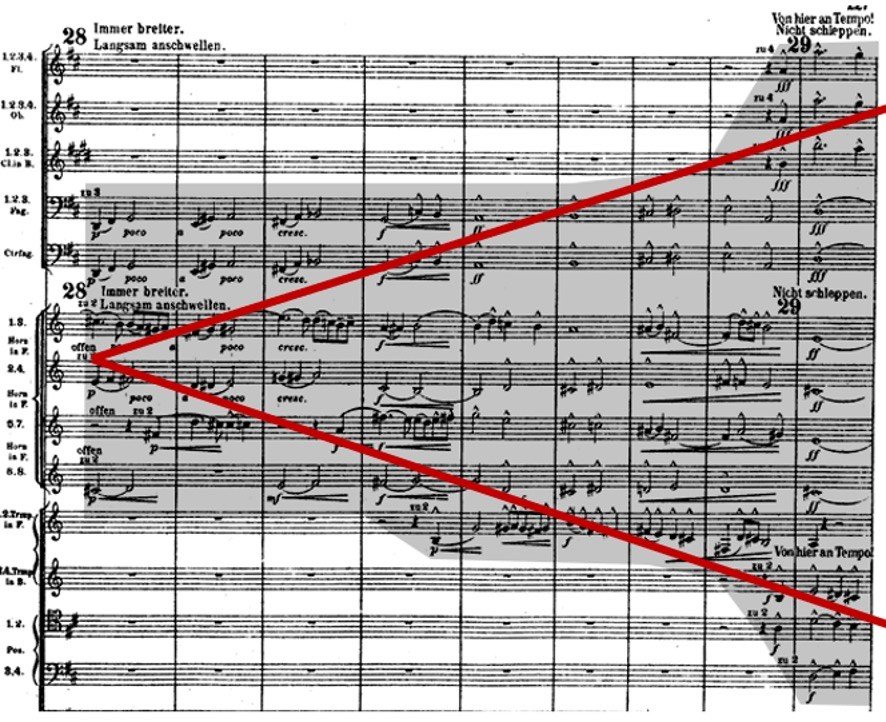

At 20:29 (Video Excerpt 2), the strings enter more fully, with the cellos in the lead. Mahler calls for both a dynamic and textural crescendo, increasing the written dynamic while gradually adding instruments. This creates a brilliant overall swelling effect—from piano to triple-forte—achieved through the staggered entrance of nearly all remaining wind and brass players across several measures. As Meghan Goodchild observes, orchestration manuals such as Rimsky-Korsakov’s typically describe orchestral crescendos as unfolding in a specific order: beginning with the strings, followed by the woodwinds, and culminating in the brass (Goodchild 2016, 37). While this progression is relatively common, Mahler inverts it here, allowing the brass to enter first, with the woodwinds joining to enrich the texture and intensify the dynamic. Figure 1 shows this buildup (to remain concise, it includes only wind instruments; the strings are assumed to be playing continuously and steadily increasing in dynamic here). I have shaded the notes in the score to highlight the progressive instrumentation that shapes this massive orchestral crescendo.

Video Excerpt 2 (20:29-21:59): https://youtu.be/bKCn1fJlPfE?t=1229

Figure 1. Entry of wind instruments following 20:29 to create a textural crescendo.

At this point, Mahler’s richly textured orchestration has formed a vast, resonant sphere of sound—so immense that it seems to have reached its limit. In their article, “Exploring emotional responses to orchestral gestures,” Goodchild, Wild, and McAdams (2019) discuss the emotional reactions of listeners as they hear various orchestral gestures, including crescendos. Their research has demonstrated that orchestral crescendos tend to elicit strong emotions, with particularly strong emotions present at the climax of a crescendo (Goodchild et al., 35). Here, the melody advances through the strings, intensifying through the vast orchestra, provoking a visceral, perhaps even ecstatic, response. At 22:00 (Video Excerpt 3), Mahler instructs the woodwinds and brass, Schalltrichter in die Höhe—to raise their bells toward the audience for maximum projection. As the melody nears its cadence and the ensemble approaches the limits of dynamic intensity, the sound becomes too powerful to contain. Finally, at 22:16, the music explodes at its cadence into a glorious cymbal crash.

Video Excerpt 3 (22:00-22:19): https://youtu.be/bKCn1fJlPfE?t=1320

Moe Touizrar, with his work on the symbolism of sunlight in orchestral music, interprets this kind of orchestral crescendo as evocative of a sunrise, with each new instrumental addition contributing to an expansion of sonic space. According to this framework, the cymbal crash is the apex of the phrase, representative of sun erupting into view over the horizon. While most of the music in Mahler’s 3rd Symphony is pitched, it is notable that he chose this point to employ the unpitched sizzle of the cymbals. This aligns with Walter Piston’s characterization of the cymbal as possessing “a dynamic range from the softest whisper to a triple forte of incandescent power” (Piston, qtd. in Goodchild 2016, 38), a quality that makes it, in Goodchild’s words, “a brilliant means of adding excitement to the orchestral crescendo” (2019, 38).

In this recording, conductor Myung-Whun Chung cues the cymbal player with an expression seemingly reserved for only the most momentous orchestral events. The musician rises to meet the grandeur of the moment, delivering a luminous crash that seems to burst forth from the collective intensity of the ensemble. This moment is nothing short of amazing and certainly deserves a place in the gallery of Amazing Moments in Timbre.

References

Dobreff, Nick. 2024. “Exploring Mahler’s Third Symphony: A Journey Through Nature and Humanity.” Colorado Symphony Blog, April 3, 2024. https://coloradosymphony.org/exploring-mahlers-third-symphony/.

Goodchild, Meghan. 2016. Orchestral Gestures: Music-Theoretical Perspectives and Emotional Responses. PhD diss., McGill University. https://www.mcgill.ca/mpcl/files/mpcl/goodchild_2016_phdthesis2.pdf.

Goodchild, Meghan, Jonathan Wild, and Stephen McAdams. 2019. “Exploring Emotional Responses to Orchestral Gestures.” Musicae Scientiae 23, no. 1: 25–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/1029864917704033.

Kim Cl Deok 김클덕. 2011. “Mahler Symphony No. 3 (6mov – VI. Langsam. Ruhevoll).” YouTube video, 25:28. May 28, 2011. https://youtu.be/bKCn1fJlPfE?si=AqkmSu1gpnNpbGcO

Mahler, Gustav. 1974. Symphony No. 3. Vienna: Universal Edition.

Touizrar, Mohamed. 2019. From Ekphrasis to Apperception: The Sunlight Topic in Orchestral Music. PhD diss., McGill University. https://www.mcgill.ca/mpcl/files/mpcl/touizrar_2019_phdthesis.pdf