Hearing Form in Phenomenological Music: An Analysis of Molly’s Song 3 – Shades of Crimson by Rebecca Saunders

Hearing Form in Phenomenological Music: An Analysis of Molly’s Song 3 – Shades of Crimson by Rebecca Saunders

Timbre and Orchestration Writings

by Joshua Rosner

Published: June 16, 2025

Introduction

The music of Rebecca Saunders (b. 1967) is all but absent from theoretical and musicological discourse with the notable exceptions of two recent publications: Dubiel’s (2017) analysis of Crimson and McMullan-Glossop’s (2017) application of color theory terminology to describe Saunders’ timbral and textural approach to composition. An active composer since the early 1990s and the 2019 recipient of the Von Siemens Prize, Saunders’ work is written in a distinct idiom, drawing equally upon “postwar German fastidiousness and expressionism and experimental, Cageian concentration…” (Service, 2012). Her music is marked by the exploration of noise, pitch, and silence, the use of extended instrumental techniques, and uncommon combinations of instruments. Traditional music theoretical analytic techniques are insufficient to fully describe the prominent features of Saunders’ music: timbre, texture, noise, and silence.

Hasegawa, in reviewing From Scratch: Writings in Music Theory, proposes that “Tenney’s temporal gestalt theory could be a powerful tool in the exploration of what Aaron Helgeson has called ‘phenomenological music,’ which includes the works of Salvatore Sciarrino, Helmut Lachenmann, Pierluigi Billone, Chaya Czernowin, and Rebecca Saunders” (2016, 86). Music theory’s inclusion of phenomenology and gestalt theory as well as a paradigm shift toward the perspective of the listener are reflective of the growing need to adapt music theory to accommodate contemporary musical practices.

Hasegawa’s proposition invites a reexamination of phenomenological ideas and applications of gestalt theory in order to derive a new analytical method based on the perception of salient musical features. To that end, I introduce four propositions regarding salience and a new analytical framework to facilitate the inclusion of music like that of Saunders’ into the analytical discourse. In order to hear form, listeners must be able to group similar sounds together and intentionally attend to specific musical foci while also noting significant changes based on salience, defined as the attention-grabbing strength of a musical element, to determine sectional boundaries. I demonstrate this process by interrogating my experience listening to Musikfabrik’s (2001) recording of Molly’s Song 3 - Shades of Crimson (1995-1996) for alto flute, viola, steel-stringed acoustic guitar, 4 radios and a music box by Rebecca Saunders.

Rebecca Saunders

The music of Rebecca Saunders has been described as phenomenological music but also as a continuation of the Lachenmannian concept of musique concrète instrumentale (McMullan-Glossop, 2017). Saunders investigates the array of available sounds within a given instrumentation, specifically concerned with how the sounds can be fused together and worked against each other (Ellward, 2008). While it is rather commonplace for composers to work closely with musicians while developing a piece, Saunders, following Lachenmann, strives to physically explore the instruments herself.

The exploration of sonic potentialities of a given instrument is not only representative of musique concrète instrumentale, but also representative of the artistic practice of found objects, objet trouvé. Molly’s Song 3 - Shades of Crimson makes practical use of the concept in that it utilizes radios and a music box. This practice is not unique to a specific piece, Nettingsmeier notes that, “In addition to the instrumentalists, Chroma incorporates some objets trouvés which are added to the sound collage at predetermined times” (2012, 3). Saunders’ conceptual use of objet trouvé plays a role in her compositional process of approaching an instrument with naivete. In a composition class Saunders explains, “by trying to approach an instrument for the first time as if you had never seen it before, never played it before, never heard it before…there’s an enormous wealth of inspiration in this kind of approach. The conventional instrument is to be explored like a found object, objet trouvé” (2016a, transcription mine). Saunders evaluates timbral (instrumental), color (sonorous), and gestural similarities between the various instruments; considering what it would be like for one instrument to be (or make sounds as) another instrument.

After thorough investigation, Saunders creates a specific palette of sounds for a composition reducing all of the potential sounds that have been explored to a manageable group. Once the palette is obtained, creating the piece is like painting—navigating the space between noise, pitch, and silence, exploring a polyphonic sonority, transforming one instrument into another. In Saunders’ words, “When composing I imagine holding the sounds and noises in my hands, feeling their potential between my palms, weighing them. Skeletal textures and musical gestures develop out of this. Then, like pictures placed in a large white room, I set them in silence, next to, above, beneath, and against each other” (Adlington, 1999). Saunders’ metaphor of the white room is helpful in understanding some of the phenomenological aspects of this paper.

Theoretical Frame

Phenomenology

Because Saunders’ music has been placed in a category of “phenomenological music” it is necessary to discuss music theory’s history with the philosophical field and crucially the use of the term. A number of music scholars in the 1980s—Lochhead 1980 and 1982, Clifton 1983, and later Lewin 1986—led the engagement of music theory with phenomenology (as discussed in Kane, 2011). As Tenney wrote in a review of Clifton’s Music as Heard, “perhaps no philosophical system has a greater potential for solving certain current problems of music theory than phenomenology…music, after all, is hardly anything more (and it is certainly not less) than its ‘appearances’ in the phenomenological sense” (Tenney, 1985, 200 as quoted in Miraglia, 1995, 274).

However, since its introduction into the field of music theory, phenomenology has been defined in a myriad of different ways; often as a near synonym for experience or perception. Lochhead (2019) observes that, “The term phenomenology and its various adjectival or adverbial forms have appeared frequently in music scholarship over the last seventy-plus years. The term is used in a wide variety of ways and with vastly different meanings. And while there is an indeterminacy of meaning for any word, the term phenomenology has an unusually broad span.” Phenomenology is simply the study of phenomena (Zahavi, 2019). Phenomenologists, regardless of discipline or time period, tend to:

justify cognition with reference to evidence, i.e., an awareness of phenomena (or objects) as revealed;

believe that both real (e.g., a chair) and ideal objects (e.g, conscious life) can be made evident and known about;

embrace inquiry into both objects as they appear and the act of appearing; and

focus on description rather than explanation (Embree and Mohanty, 1997).

As a philosophical approach, phenomenology attempts to reveal the taken-for-granted practices, conventions, and presuppositions that shape perception. In Davis’ words, “phenomenology seeks to give accounts of appearances as processes—of the coming-to-appear” (Davis, 2019, 4).

Given the definition and method presented above, labeling certain music as phenomenological may come across as problematic as all musical experiences can be examined critically using the phenomenological method. Saunders’ music for me and Sciarrino’s music for Helgeson (2013) are phenomenological because they compel listeners to refuse to take experience for granted. The exemplars of phenomenological music that Helgeson puts forth share a few notable attributes. First, these composers utilize extended and innovative performance techniques forcing the listener into unknown territory. Second, the music tends to focus on timbre and texture more so than other parameters. Third, phenomenological music presents the listener with sounds at the periphery of perception; very quiet sounds emerging or disappearing into silence, and sounds with indeterminate sound sources. These three qualities of phenomenological music encourage a listener to interrogate their listening experience. The unfamiliar features heard in phenomenological music solicits an uncovering and excavation of the listening experience that cannot be taken for granted.

Temporal Span

In order to interrogate how musical phenomena appear to me while listening, several phenomenological concepts require introduction. First, the temporal span: a non-linear perceptual time in which “successive events are available to our consciousness (‘all at once’)” (Helgeson 2013, 15). To Husserl, the present is experienced as an ever-progressing temporal interval bounded by retention, resonance of the past, and protension, expectation of the future. Ihde describes the temporal span as an aspect of experienced temporality elaborating, “I do not hear one instant followed by another; I hear an enduring gestalt within which the modulations of the melody, the speech, the noises present themselves” (2007, 89). Temporal spans in the context of this paper refer to durations of time where my attention is focused on a specific sonic object.

The sonic object, intentional object, and imaginative variation

The concept of the sonic object, l’objet sonore, was introduced by Pierre Schaeffer in 1948. Reacting to the growing need for a new system to address new music, music from other cultures, and new music technology, Schaeffer and colleagues advocated for a phenomenological approach to music. According to Kane, “A sound object is an intentional object whose essential properties can be disclosed through a method of imaginative variation” (2014). In the context of Husserlian phenomenology, the intentional object refers to the object as it appears in consciousness, regardless of whether it exists in the external world, and as something that can be identified across varying appearances.

Imaginative variation, also known as eidetic variation or free phantasy in Husserlian phenomenology, is a method of systematic variation of examples of the object under consideration (Moran and Cohen, 2012). This process allows us to comprehend the essence of the object as it appears in consciousness. By systematically varying examples, we can identify invariant structures—what stays the same across different appearances. I adapt this concept and consider this phenomenological exercise as a means of grouping musical elements together; imagining a thread of unity running through a multiplicity of variants: the essence of a sonic object.

Crucially, the sonic object is dependent upon attention. Ihde (2007) describes how attention shapes intentionality, framing it as a kind of temporal focusing. Within a given temporal span, the auditory attention is directed, either due to the listener’s preferences or salient features of the auditory signal, to a specific sonic object. The object is foregrounded and other auditory information is moved to a perceptual mid-ground and/or background. Being able to imagine a thread of unity running through different variations of a sonic object is not only a phenomenological exercise, but also a way of attending to what remains constant—what becomes the temporal focus within a given span.

Auditory Fields

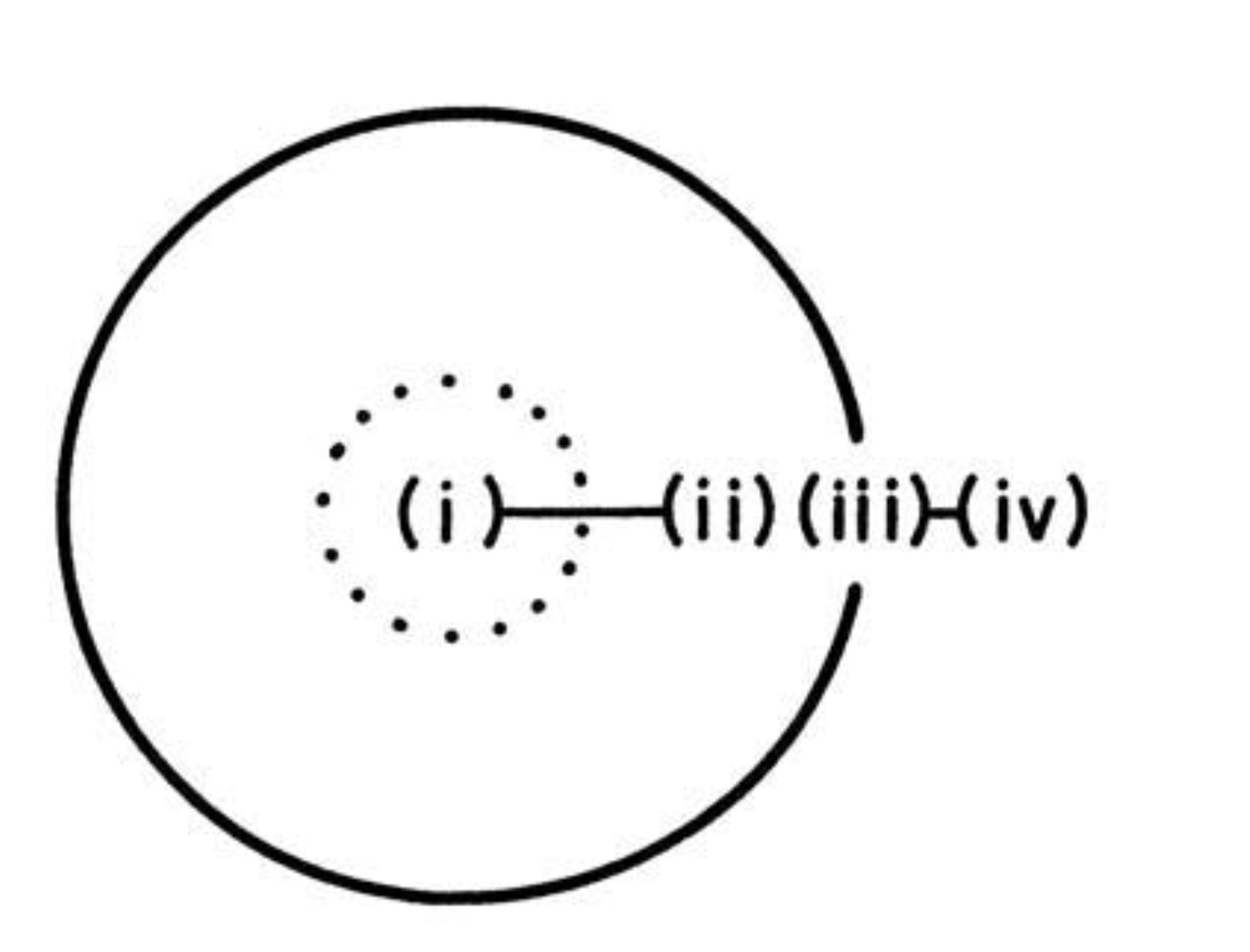

The most pressing phenomenological concept for this paper is that of the auditory field. Helgeson (2013) draws significantly upon the concept of the auditory field for his analysis of Sciarrino’s Infinito Nero, however, my use of the concept differs. Ihde describes a visual field, as seen in Example 1, consisting of four parts:

(i) a focal core, that which stands out before . . . the central “object” …; (ii) the peripheral fringe, situated in relation to the core but never absent even if not explicitly noted; (ii) shades off to (iii), the horizon, which is the ‘border’ or limit of the visual field and its “beyond.” . . . But beyond the “edge” of the visual field nothing is given as present, the “beyond” of the horizon is an absence, or emptiness (iv) (Ihde, 2007, 38-39 as quoted in Helgeson, 2013).

There are two ways to adapt the visual model to the auditory realm; either visibility can map onto audibility or space can map onto time. In Helgeson’s article, the auditory field is often used to discuss the liminality of sounds, suggesting visibility corresponding with audibility. Because attention is of primary importance to the present inquiry, space maps onto time. My construction of an auditory field spans, what Ihde refers to as a field duration — “the totality of what is or may be ‘within’ temporal awareness” (2007, 95) — what I argue is a temporal span. In relation to Example 1, my notion of a temporal span consists of (i) a temporal focus in the form of a sonic object and (ii) non-focal sonic information which competes for my attention bounded by (iii) the horizon, the horizon, a duration framed by retention and protention, which define the temporal limits of the field, and (iv) recollection and anticipation of the next auditory field.

When a listener moves from one temporal focus to the next, a new auditory field is generated. As successive fields are experienced, retention gives way to recollection, i.e., auditory memories that are still available but not part of the current temporal span. Our prior expectations (protention) abruptly change or gradually morph into retention of the subsequent auditory field when our expectation of the continuity of a temporal focus is confounded.

It is worth noting that the visibility and spatial aspects of the visual field and their auditory counterparts, audibility and time respectively, are not mutually exclusive. As sounds move beyond the auditory horizon in either domain, they do not cease to exist. Consider standing at a street corner and hearing a siren. Due to past experiences, it is possible that a listener would be able to identify the siren as belonging to an ambulance as opposed to a firetruck. As the siren physically moves away from the listener and beyond the listener’s ability to hear it, a listener familiar with the layout of the city could potentially track the route that the ambulance takes to the nearest hospital. The sounds beyond the auditory horizon are imagined listening experiences and associations as well as context based sonic memory and anticipation.

In order to better understand how a listener structures Rebecca Saunders’ music, the necessary phenomenological concepts have been discussed. The auditory field, a temporal span with a temporal focus, is constructed based on attention. This analytic device is useful in describing swaths of music where segmentation is perceptually ambiguous. Though attention and phenomenological temporality are crucial, we turn our attention to gestalt techniques adapted from Tenney and other theorists to better understand grouping and segmentation principles.

Grouping, Segmentation, and Temporal Gestalt

Drawing significantly from visual gestalt perception, Tenney’s central tenet in his thesis Meta+Hodos (1964) and its subsequent reification in “Temporal Gestalt Perception of Music” (1980) was that of hierarchical structure: “A piece of music does not consist merely of an inarticulate stream of elementary sounds, but a hierarchically ordered network of sounds, motives, phrases, passages, sections, movements, etc.—i.e., time-spans whose perceptual boundaries are largely determined by the nature of the sounds and sound-configurations occurring within them” (Tenney & Polansky, 1980, 205). The basic principles of temporal gestalt perception are that sonic similarity and/or temporal proximity of an acoustic parameter (such as timbre, intensity/volume, register, pitch, etc.) of two gestalts will group them together at the next highest level and sonic difference and/or temporal distance of an acoustic parameter of two gestalts will separate them at the next highest level. Tenney and Polansky’s (1980) terminology for these levels are, starting from the most basic, element, clang, sequence, segment, section, piece. Multiple elements form a clang, multiple clangs form a sequence, and so on and so forth. Also referencing gestalts, Hasty came to a similar conclusion in “Segmentation and Process in Post-Tonal Music” (1981).

Rather than treating temporal gestalts and auditory fields as separate frameworks, I suggest they offer complementary perspectives on the same phenomenon: the organization of sound through attention over time. Temporal gestalts name the hierarchically structured groupings that emerge; auditory fields describe the attentional organization of sounds as they appear. Auditory fields are not necessarily fixed spans but attentional structures that can vary in scope, such that narrower fields may be subsumed within broader ones. Varying scales of attentional focus—from brief gestures to entire movements—can generate nested auditory fields within which multiple events are held in consciousness “all at once.” Based on Ihde’s idea that, “[w]ithin auditory temporality the temporal span shows itself as containing a multiplicity of auditory events that are intentionally graded,” I propose that multiple temporal spans—conceived as enduring gestalts with temporal foci—might be understood as nested within a broader attentional span and grouped into higher-order gestalts at the level of the section or piece.

Tenney & Polansky’s (1980) framework; however, does not account for attention. Any temporal span is subject to the cognitive limitations of human attention. The structure of Husserlian temporal awareness—bounded by retention and protention—conditions the possibility of the entire piece appearing simultaneously to consciousness. I can, however, conceive of the piece in this manner. While I can conceptually organize musical events into larger structures, my perceptual access to these hierarchies remains limited due to attentional constraints. As I listen, I can group together elements into clangs, clangs into sequences, sequences into segments, and often segments into sections. When applied to an entire piece, the auditory field loses precision, serving mainly to separate music from extramusical sound rather than reveal inner structural relations. My cognition of temporal spans allows me to conceive of groupings at any gestalt level regardless of the limitations of my attention.

Gestalt theory and music cognition research have shown that listeners are able to conceive of a series of sounds as a relatively unified entity, such as the series of individual notes that are recognized as a melody. Drawing on classical phenomenology, Godøy calls this phenomenon the “flux-to-solid” transition (Godøy 1997; 2014, 224-225). In order to comprehend the metaphorically solid musical entity, Godøy (2019) describes musical shape cognition, comprehension of discrete musical elements as unified shapes, as proposed by gestalt psychologists as well as Schaeffer.

Gestalt theory has been highly influential on music cognition, including Bregman’s Auditory Scene Analysis (1990). Discussing his connections to phenomenology, Bregman reflects, “It shows that there is a tendency for similar sounds to group together to form streams and that both nearness in frequency and in time are grounds for treating sounds as similar. The gestalt psychologists had shown that, in vision, objects that are nearer in space (or more similar) tend to form tighter perceptual clusters. The same principle seems to apply to audition” (2005, 33). Most theorists (such as Lerdahl & Jackendoff 1983, Hanninen 2012, Howland 2015) agree upon temporal proximity and sonic similarity as factors of grouping and temporal distance and sonic difference as factors of segmentation.

In her comprehensive recent work on segmentation and associative organization, Hanninen (2012) defines three domains in music analysis—sonic, contextual, and structural—and five levels—orientations, criteria, segments, associative sets, and associative landscapes. Associated with the three domains, Hanninen defines three orientations, different ways of conceptualizing or attending to music; a disjunctive orientation, an associative orientation, and a theoretic orientation. Because of my concern with grouping and segmentation, my model engages with both the sonic domain and disjunctive orientation, which engage with individuation, difference, and segmentation of sonic events, and the contextual domain and associative orientation, which pertain to similarity, association/associative organization, and chunking groups of sound events.

However, in much music theoretical research, the focus has been to observe this principle in the score and turn away from the listening experience. Maler’s dissertation echoes this, arguing that past scholarship “emphasizes the composer’s scaffolding rather than the listener’s construction of phrases in time” (2018, 55-56). Tenney’s theory was transformed into an algorithm to measure the gestalt hierarchy of monophonic music via the score. By measuring changes in each sonic parameter against time, Tenney & Polansky’s algorithm was able to segment a score based off of proposed theoretical groupings. There are three major shortcomings to this model: 1) Scores, not sounds, were analyzed, 2) all parameters were treated as equal, and 3) only monophonic music can be analyzed. Lefkowitz & Taavola (2000) and Uno & Hübscher (1994, 1995) revised the algorithm attempting to weight parameters specific to a given piece and to accommodate polyphonic music respectively. In all scenarios, the analyses presented assumed no variation in listeners. The framework I propose acknowledges that no two listeners are the same and that the same individual can have different listening experiences to the same work or recording. There is still significant merit in utilizing the foundation of temporal gestalt perception as a basis for analysis.

Salience

Salience is an important term for musical analysis, and this analysis requires a specific definition. To Maler, a salient musical element is one “that emerges as especially important in making determinations about formal constituents” (2018, 56). Lerdahl & Jackendoff (1983) refer to salience as a form of emphasis—a “phenomenal accent.” Dibben (1999) goes so far as to refer to salience as “structural importance.” Berlyne (1971) and Margulis & Beatty (2009) refer to “arousal potential” and define it as the “psychological strength” of a stimulus pattern. Salience, in the context of this analysis, is the attention-grabbing strength of a stimulus and refers to the prominence or relative prominence of conspicuous musical elements. Therefore, the more salient a musical event or parameter is, the more likely it is to appeal to the attention of a listener. I assert that salience is the primary factor in structuring a musical work, i.e. hearing form in a musical work, and put forth the following four propositions.

Proposition 1: The most salient feature of music is the dichotomy between sound and silence. At the most basic level, music is a series of salient sonic events separate from the mundane sound world. Musical events that are grouped together to be perceived as gestalts are often divided and bounded by silence. Silence can also function as a culmination to a series of sonic events, providing a moment of repose for a listener. According to Margulis, “each piece of music in the Western tonal tradition shares one basic endeavor: to justify breaking the silence at its start and to motivate returning to silence at its end” (2007a, 245 see Kramer 1988). Deutsch (1999) has discussed silence as a mechanism in segregation. In keeping with music psychologists, Cone (1968) analogized silence’s function as a boundary to that of a frame, an analogy also used by Saunders. Silence has been identified as a source that contributes to cadences (Barash 2002). Margulis (2007b) suggests that silence affords i) the perception of a boundary or an ending, ii) an attentional shift inward, phenomenologically allowing us to listen to ourselves listening, and iii) comparison to language (pauses, spontaneous narrative, etc.).

Proposition 2: Novelty is salient. Smith (2014), studying listener differences in the perception of musical structure, found that acoustic novelty is correlated with boundary salience. While acoustic novelty is a necessary but insufficient condition to create a boundary, the degree of novelty is a good predictor of boundary points and indicates that novelty plays a role in attention-getting. Berlyne in the investigation of aesthetics and psychobiology defines arousal potential as, “the ‘psychological strength’ of a stimulus pattern, the degree to which it can disturb and alert the organism,” something partially predicated on “properties such as novelty, surprising-ness and complexity” (Berlyne 1971, 70 as quoted in Margulis & Beatty, 2008, 66). Bailes & Dean state that “a decrement attracts attention less powerfully than an increment. Biologically, it is understandable in terms of the cost-benefit of attentive input that it is more useful to detect the input of a new sound, which may represent the arrival of a new source of danger, than the removal of one…” (2007, 91).

Proposition 3: Salience is hierarchical. Lerdahl (1989) suggests that in the absence of pitch hierarchy, listeners create an event hierarchy based on salience, and Imberty (1993) has also proposed a perceptual hierarchy of changes and events that is directly linked to the relative salience of musical elements. Tiits proposes that “[t]he listener’s attention is often divided between a number of things: simultaneous progression of musical form on several hierarchical levels…)” (2002, 37). Caplin’s (2001) minimal definition for the form of a musical work depends on the hierarchical arrangement of perceptible and discrete time spans; chunks that have a formal organizational role. In keeping with the aforementioned definition of salience, all audible musical events are salient; some, however, are more salient than others. Additionally, as hierarchical arrangement is a central aspect of gestalt theory, musical events are structured hierarchically predicated on their respective salience.

Proposition 4: Salience is subjective. Composers and performers have the ability to call attention to specific parameters (i.e., to make them salient). Godøy, however, acknowledges that, “[g]iven our freedom of mental focus in listening…we may zoom in and out at will to whatever feature(s) we are interested in, progressively exploring what we believe are perceptually salient features of the music at different timescales” (2014, 228). Regarding the ability to extract information from an auditory scene, Thompson et al. (2011) echoing Carlyon et al. (2001) demonstrate that listener segmentation of multiple sound sources can be influenced by attention. Smith states “by manipulating the attention of participants, we are able to influence the groupings and boundaries they find most salient. From the sum of this research, we conclude that a listener’s attention is a crucial factor affecting how listeners perceive the grouping structure of music” (2014, iv). Acknowledging the individuality of a hypothetical listener, this analysis cannot support any specific hierarchy of salience; however, salience remains hierarchical for each listener and potentially each experience of a particular musical work.

Methodology

Silence

Prior to applying these propositions and concepts to analysis, it is worth excavating Saunders’ unique view of silence and examine how it relates to Proposition 1. While Cone (1968) and Saunders (2004-2006) describe silence as a frame, Saunders offers an alternative metaphor; that of silence as canvas,

“Nevertheless, even though there is very very few moments of pure musical silence, silence is regarded as the canvas on which I have written all the music in a way. So, it’s as if the sounds are pulled out of and disappear into that canvas again. Or as if my canvas is some sort of undulating, moving resonance on which I then draw the sounds. And that's very important because even if the sound is an explosion out of silence the silence is still there and that potential is still there so I'm very very aware when I write that this is what I write with” (Saunders, 2016b)

Continuing with the analogy from visual art, recall Saunders’ metaphor of pictures in a white room - the sonic gestures (pictures) existing in a shared acoustic void full of potential (the room).

To demonstrate, I will augment Saunders’ metaphor slightly. Rather than consider the pictures being hung, imagine them painted directly on the wall, which functions as a giant canvas. The most prominent “frames” are the doorframes of the entrance and exit to the room. These may or may not be silences in the sense of inaudibility but rather the lack of painting in the room (i.e. the musical sound world and its distinction from the mundane sound world). Sometimes Saunders will place frames around the painted portions of the wall, helping me distinguish them from the wall. Other times she will allow the paint to fade seamlessly into the wall itself attenuating the ability of a lack-of-paint to serve as a boundary. Saunders delightfully complicates the situation even more by involving the presence of the wall in the middle of some of the paintings.

While I can conceptualize “silence-as-canvas” and “silence-as-frame” in discrete ways, silence’s function is still intertwined with listener attention. In the same way that visibility maps onto audibility, I can conceive of sounds emerging from and retreating into the canvas, the hairpin dynamics that are ubiquitous in phenomenological music. Blurring the boundaries between sound and silence attenuates the frame and suggests a canvas. When silence acts as a canvas, I can still focus on the essence of a sonic object within a temporal span even if nothing is sounding during the instant I choose to interrogate. When silence functions as a frame, I am no longer able to attend to a sonic object. These silences correspond with the space to time analog. Moving through Saunders’ gallery, when the presence of the wall helps me distinguish one painting from another, I comprehend silence as a frame.

Regardless of silence as canvas or frame, the dichotomy between sound and silence (Proposition 1) is still the most salient part of my experience of Saunders’ music. Especially since silence encourages me to reflect on my listening experience and predict what comes next, I find that canvases help me keep a sonic object in focus and that frames force me to consider an alternative focus. Imagined continuity of sound (as well as protention and retention) would be a form of silence acting as canvas —moments that not only engender the phenomenological method but also allow the listener to focus on silence. In the upcoming analysis, my categorization of silence as frame or canvas reflects whether I perceive the silence as assisting my intentional attentional focus (canvas) or encouraging me to attend to new material (frame).

In keeping with the aforementioned gestalt theories, it is possible for silence to function as a canvas in one level and a frame in another. For instance, a silence can separate two phrases but assist me in finding unity between those phrases at a higher level. When I refer to canvas or frame in my analysis, I am focusing solely on the section level. I should also note that silence is often subsumed under the parameter of loudness (musical dynamics or amplitude). This is logical as silence is the attenuation of amplitude, however, I propose that noticeable changes in dynamics reflect Proposition 2 (novelty) and are categorically different than the sound/silence dichotomy.

Novelty

Novelty not only refers to new musical material but also sonic information that confounds our expectations. For instance, contrasts in dynamics, timbre, texture, and tessitura/register have been found to be relevant for realtime segmentation tasks (e.g., Deliège, 1989; Clarke & Krumhansl, 1990; Lalitte et al., 2004; Taher et al., 2018). Proposition 2 reflects these findings and most importantly can be found in each sonic parameter. Whether or not a sudden increase in volume or a never-before-heard timbre is more novel or salient is up to each listener and each listening experience (Proposition 3).

Two of my criteria of phenomenological music dealt with unfamiliarity — extended use of non-default and novel instrumental playing techniques and a focus on timbre/texture over other parameters. Phenomenological music sounds novel to most listeners partially because the elements of music that we rely on to comprehend non-phenomenological music are missing. One goal of my analysis is to describe my experience listening to Saunders though I acknowledge that my fascination with Saunders’ music and my extended exposure to it and other contemporary musical practices certainly influence how I hear form. My experience is reflective of Alex Ross’ account of listening to Saunders’ music, “you crane this way and that, wondering which instruments are playing” (2013).

Proposition 2 raises the question of how a listener copes with unfamiliar (and uncomfortable) sonic situations. Music like Saunders' creates environments where some listeners may be too overwhelmed by the novelty and unfamiliarity to attend to any changes in musical parameters. Kozak acknowledges that, “…sequences of perceptual discontinuities do not make for the easiest listening experience, as one’s attention has to constantly shift from one register to another.” (2017, 209) I hypothesize that a listener unfamiliar with phenomenological music may be too overwhelmed by the novelty to perceive structure. Listener-generated questions along the lines of “what was that?” or “what is going on?” divert attention away from the temporal focus of a given temporal span. Often, these moments allow listeners to attend to a new sonic object. This does not discount the possibility that some listeners may hear all moments as novel, segment accordingly, and come away from the listening experience without a meaningful cogitation of the form of the piece.

Hierarchy and Subjectivity

Propositions 3 and 4 are important concepts to consider but are not discussed in depth in my analytical demonstration. The auditory fields I present reflect my attention and therefore my hierarchical arrangement of musical events (Proposition 3). Explicitly, my analysis reflects my subjectivity and aesthetic preferences (Proposition 4). It is worth noting that I have chosen to analyze a specific recording as opposed to all available realizations of Saunders’ composition. The selected recording by Musicfabrik is the only studio recorded version currently available and certain effects are more perceptible compared to the available live recordings. My analysis will evaluate my listening experience in detail; tracking my attention through auditory fields and advocating for gestalt groupings and segmentations based on my propositions regarding salience.

The various parameters are evaluated in hierarchical order (Proposition 3) regarding how important each of them was to my experience (Proposition 4) hearing form in the piece: silence, timbre, intensity, register, and pitch. This is not to say that other perspectives are invalid. On the contrary, this analytical technique is designed for individual perceptual differences and could be used to compare different recordings of the same musical work as well as different listening experiences to the same recording.

This analysis, just like any analysis, will affect the listening experience and will likely interfere with some auditory illusions that Saunders has carefully crafted. If the reader has not yet listened to the Musikfabrik recording of Molly’s Song 3 - Shades of Crimson from the record Quartet, I encourage the reader to listen prior to reading any further. Aesthetically, not knowing how Saunders’ creates her sonic landscapes instigated my preoccupation with the music of Saunders. My analysis and the ideas presented are a direct result of curiosity, wanting to know how the trick is done, or as Lochhead (2006) frankly inquires, “how does it work?” At this time, I invite the reader to listen to the aforementioned recording.

Molly's Song 3 – Shades of Crimson

Background

In the spring of 2013, I first heard Molly’s Song 3 and could not believe my ears. None of my previous musical experiences had prepared me for the timbral transformations and modulations, the nuances of subtle variations on a single pitch, and the astonishing blends of instrumental identities. As a guitarist with all the requisite materials to perform the piece — a steel-string guitar, metal bottle neck, and e-bow — I was further dumbfounded since I had never considered using my instrument used in this manner. Even the most familiar performance techniques sounded new in this context.

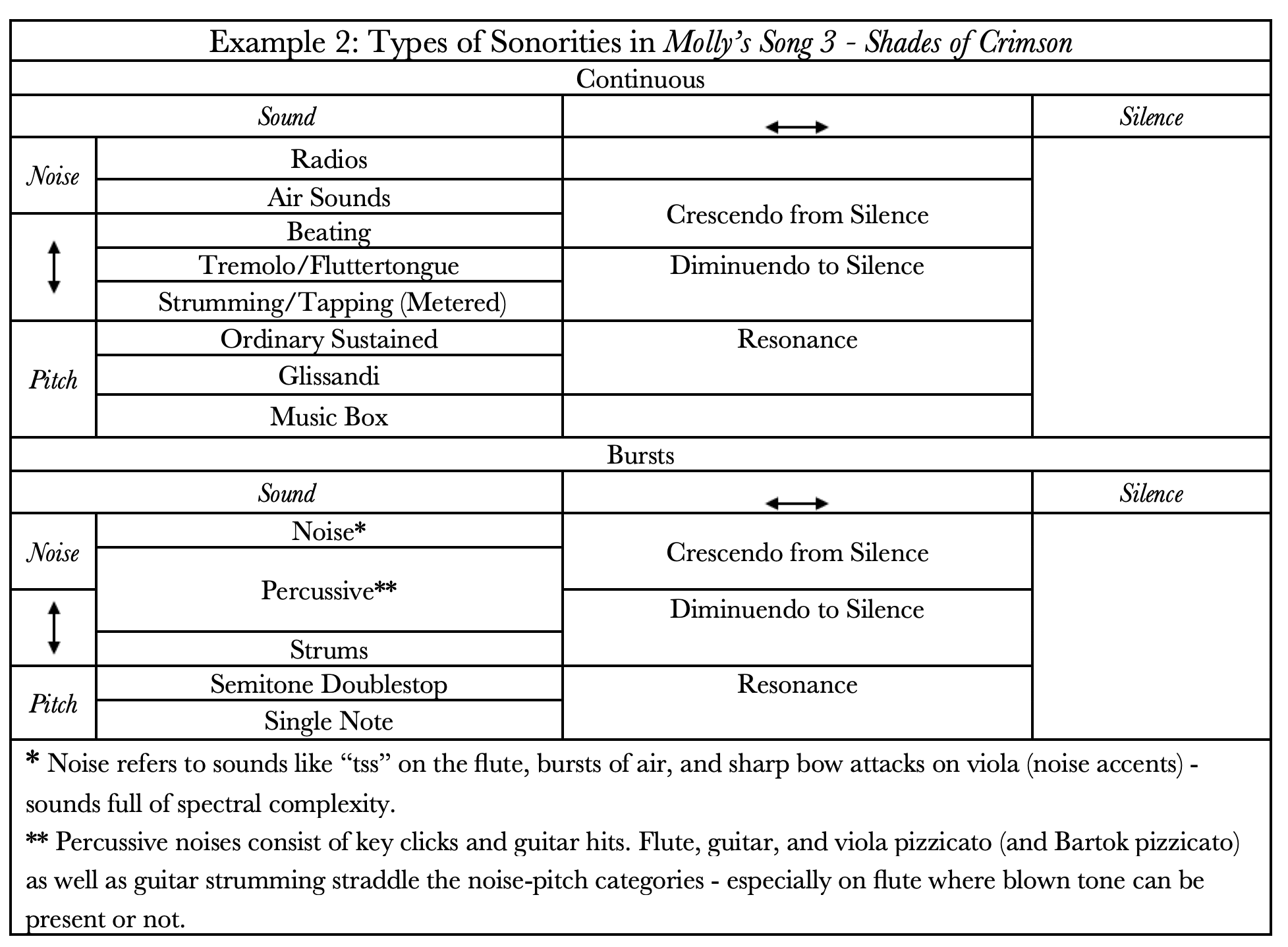

Molly’s Song 3 for alto flute (in G), viola, steel-stringed acoustic guitar, 4 radios and a music box was completed October 1996 and first performed 20 September 1997, De Markten, Brussels, by Ensemble Q-02. The types of sounds Saunders uses in Molly’s Song 3 have been aggregated in Example 2. The vocabulary I have chosen to describe the types of sounds is similar to vocabulary that Schaeffer uses to describe sound shapes.

The titular Molly refers to the character Molly Bloom from James Joyce’s Ulysses whose final monologue serves as an inspiration for much of Saunders’ work. Adlington writes, “Noting that Molly's monologue ‘flows unpunctuated for 35 pages’, Saunders asserts that Molly's Song 3 ‘seeks to sustain a musical energy strong enough to withstand the assaults of a succession of destructive events.’” (1999, 56) However, Molly Bloom is not the sole reference in the title of the work. Saunders also refers to a quote from Plato’s Timeaus in which he describes how humans perceive color.

Saunders’s music has been tied to color due to the plethora of pieces named after colors. Saunders has tried to move away from speaking about color and credits an inability to name pieces and articulate her thoughts about her music as a rationale for her reliance on color metaphors, including that of the white room. There are two reasons that color is important for my analysis; subjectivity and context. Saunders responding to an interview question about her use of color names explains,

It’s incredibly subjective and color is a wonderful metaphor for music in that respect because of its subjectivity. So that’s why I was led to that. Also, when I was still studying with Wolfgang Rihm, I was there with him between ’91 and ’94 in Germany, I basically was spending most of my time with painters. In fact, I was living with a painter and this painter only worked in a certain shade of red. (2016a, transcription mine)

The subjectivity of color is a visual analog to Proposition 4 and the historical context of Saunders surrounded by red may be a significant entry point for some listeners. That being said, my experience of Molly’s Song 3 is not tied to Saunders’ specific titular references. I find myself being led on a topographical journey when I listen to her music, focusing on instrumental techniques and traversing my course through sonorities that sit on the boundaries of pitch, noise, and silence.

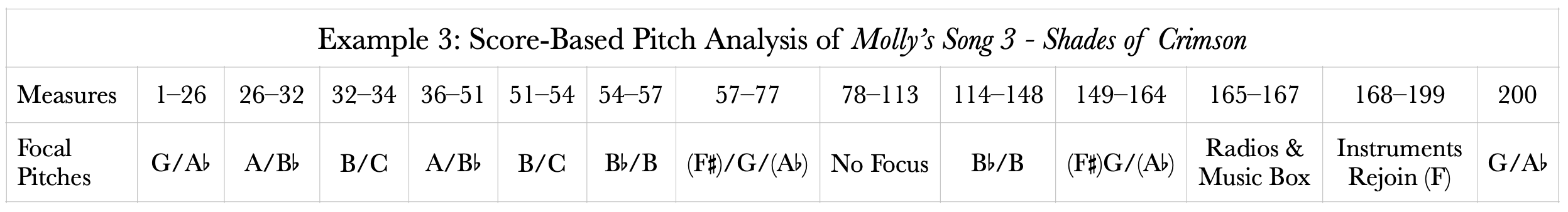

Analysis

Before I present my analysis, consider a score-based approach, as seen in Example 3. Using pitch organization as the primary structural feature, Pocknee (2008) presents four sets of focal semitones that can be heard as sectional foci: G/Ab, A/Bb, B/C, and Bb/B. Based on analysis via the score, Pocknee argues that Molly’s Song 3 is in fact a rondo where Saunders alternates back and forth between sections pertaining to sets of focal pitches. Insofar as pitch can be considered as a structuring force for me, the most salient pitch-related moments are variations of beatings and semitones around G3, which occur in the temporal foci of sections A, C, C’, and the final sonority as shown in Example 4. This score-based analysis making segmentations using pitch foci suggests a different formal reading than the one I will propose below, which is based on a close aural analysis of a specific recording.

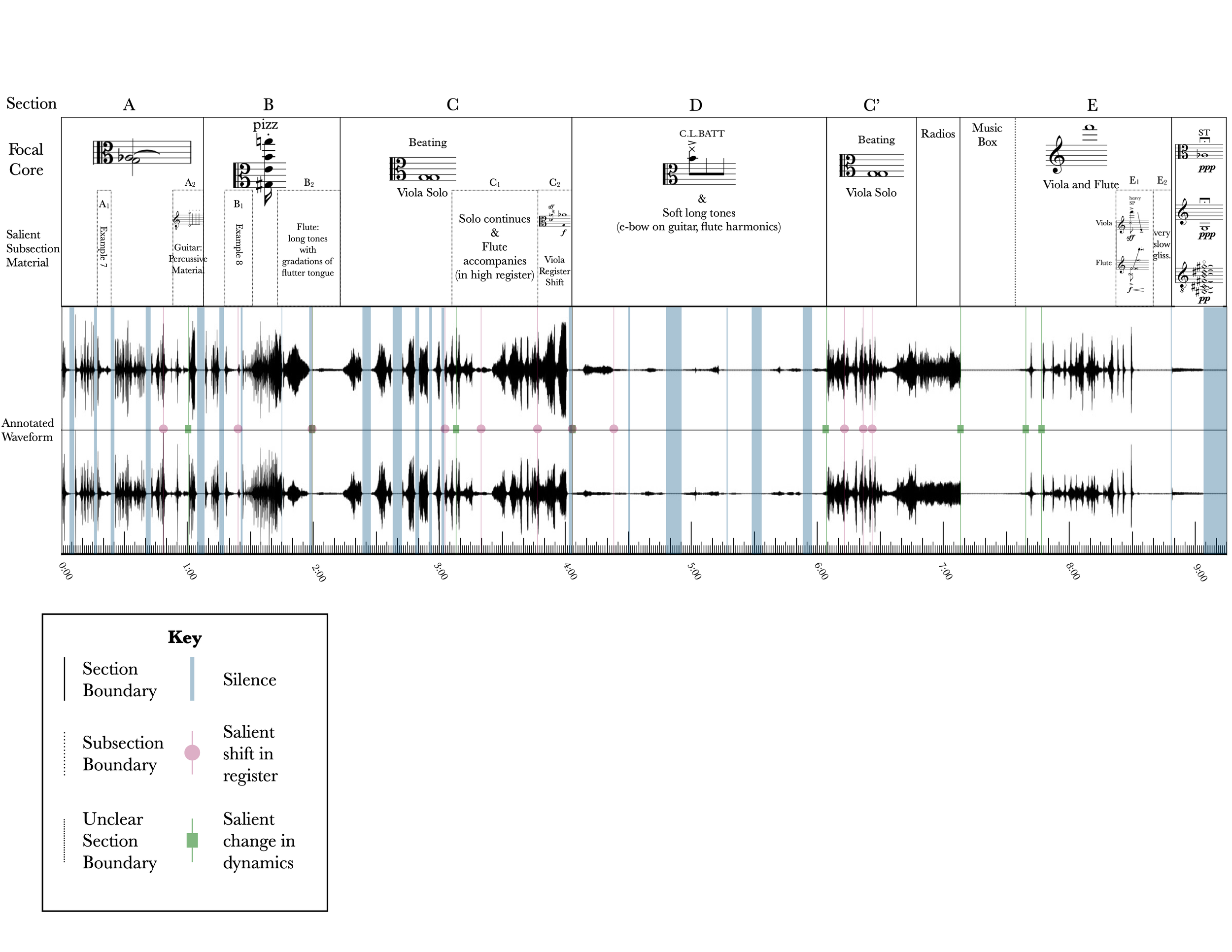

My analysis takes into consideration all four propositions and is reflective of my phenomenological and gestalt conception of structure heard in the piece. It is a visual representation (Example 4) of my structuring of the piece based on my listening experience and drawing from the work of Lochhead (2016) and Alegant (2013). Each section is representative of an auditory field at the section level, grouped together by my attention to a sonic object and segmented from one another based on shifts in my attention due to salient musical moments. Each field is placed atop a wave-form of the recording to show the duration of my focus, which is shown above the wave-form in a representation of the essence of my temporal focus.

Example 4: Visual analysis of Musicfabrik’s recording of Molly’s Song 3 - Shades of Crimson. The visual analysis demonstrates how my segmentation of the piece into sections. The diagram depicts time (in seconds) and amplitude (via the waveform). focal cores (above the waveform), and segmentation down to the subsection level. The final sonority appears as it does in the score (from top to bottom: viola, alto flute notated in concert, steel-string guitar).

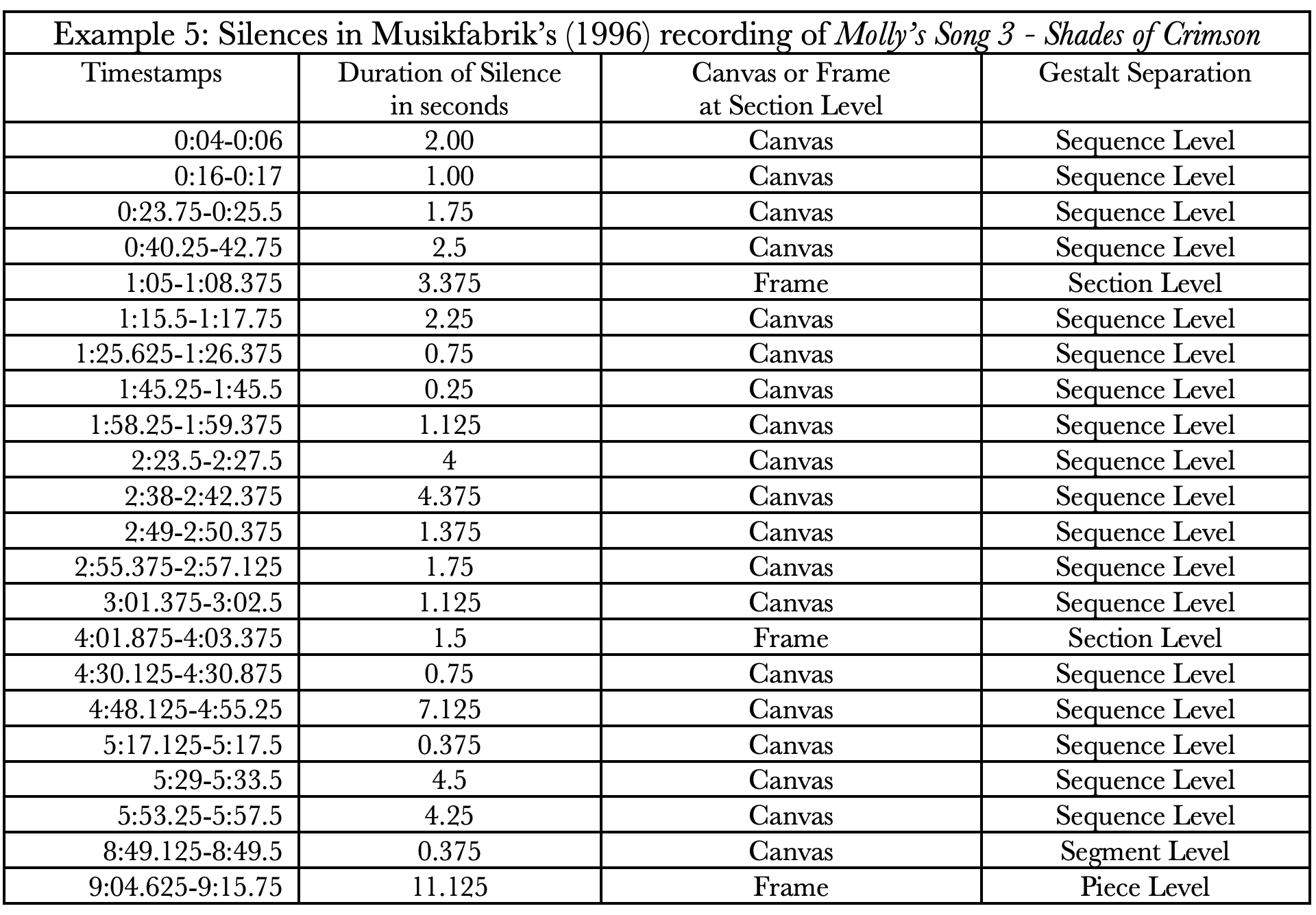

In keeping with Proposition 1, I first present the silences, shaded blue regions in Example 4, of the piece as they are the most salient feature of my listening experience. Though Helgeson (2013) acknowledges that silence cannot function as a phenomenological or Schaefferian sonic object as it only presents itself as the absence of sound, I consider silence through the temporal lens. In this regard, silence can be the focus of my attention at a lower gestalt level. Take the silence that occurs from approximately 4:48.125-4:55.25. Other than the concluding silence, this event is the longest silent episode of the piece. Even though the duration suggests a significant gestalt separation on the next highest level (silence-as-frame, i.e. concluding a section), the guitar’s sonic disappearance and gradual reappearance from nothing allows me to continue to imagine the continuity of my temporal focus and I expect the guitar to return.

Example 5 is a table of the silences heard in the piece considered at the section level of the hierarchy. I have classified them as frame or canvas depending on whether or not they segment two sections of the piece or assist in my grouping. The proposed gestalt levels are present in the example as well because silence does separate and segment musical material at a lower gestalt level.

I hear the first “silence-as-frame” at the section level starting at 1:04.25 as the flute’s resonance dissipates and 1:08.375 when the not-yet-heard pizzicato chord of the viola shatters the silence. The silences heard prior to this segment lower level gestalts (sequences), such as 0:04-0:06. The silence beginning at 1:04.25 has the longest duration of any silence heard so far and the silence is interrupted with a novel sound. Though it is tempting to equate duration of silence with level of gestalt separation, the longest silence within the piece (4:48.125-4:55.25) does not segment at the section level.

While Proposition 1 implies silence must segment two gestalts, it can also assist in grouping at a higher level. Considering the the first silence heard (2:23.5) during Section C (the first viola solo which begins at 2:13), I experience this silence as solidifying my understanding that I am no longer in Section B. While silences act as structuring agents, they also encourage recollection and imagined listening to acknowledge structure after it has passed and predict continuity of the essence of a sonic object. Unlike the silence beginning at 1:03, which separates the Section A and Section B, the sectional boundary separating Section B and C do not correspond with silences. Instead, the silences occur after the new section has already begun and it is only through the reflective experience that these silences afford that I am able to acknowledge that my attention is now focused on a different sonic object.

The novelty of sonic objects both in initial experience and in contextual juxtaposition is a crucial structural feature of the music as advocated by Proposition 2. The most salient moment of novelty is the appearance of the radios. Regardless of a listener’s familiarity with Saunders’ music, the appearance of the four radios (6:47.5) will always sound novel. Even after multiple listenings of the same recordings, the difference between instrumental playing and the radios is shocking. In the process of analyzing this piece, I have become acutely aware when the appearance of the radios will begin, yet every time I am surprised at how novel they sound compared to all the material heard previously. Because of this drastic change, the radios cause my attention to shift away from the viola and function as a structural landmark.

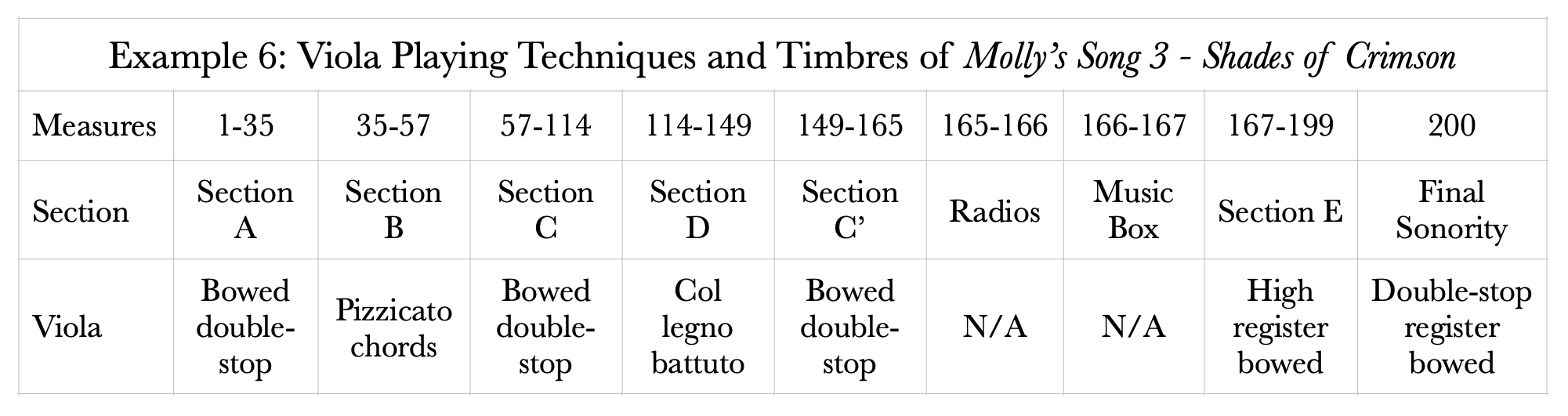

Similar timbres, sonorities, and playing techniques are useful for grouping during my listening experience. It follows that the appearance of a novel timbre is therefore a force of disjunction. A novel musical timbre, such as the viola pizzicato strummed chord (1:08) or the first appearance of the e-bow of the guitar (4:03) are two instances where timbre (in conjunction with other parameters) is a clear structuring force. Returning to Example 3, Pocknee’s (2008) proposal that Molly’s Song 3 is a rondo, I assert that tracking the playing techniques of the viola leads to a similar conclusion. Example 6 shows the playing techniques and timbres of the viola across the sections I hear in the piece. The changes in the viola’s playing techniques are indicators of sectional changes, as evidenced by the temporal foci of my attention. This is not to say that the viola only used a singular playing technique in each auditory field. The viola is significantly more varied than my visual analysis may suggest. Phenomenologically as I listened, I attended to the invariant structures of each of these sonic objects—this is why I hear section C (unaccompanied) as distinct from section A (accompanied); though both focus on the same viola playing technique. When my attention was drawn to a new technique, timbre, or sound world, I conceived of a new auditory field with a new focal core.

Novelty does not solely relate to my perception of timbre, although I suggest that timbre is involved in most salient changes. While I listen, I also notice significant changes in loudness/dynamics and register. Considering the hierarchical arrangement put forth by Proposition 3, I believe that the changes in dynamics are more salient to me (Proposition 4) as I reflect on my listening experience. Regarding loudness, there are several sectional boundaries defined by differences in amplitude. For instance, both viola solos (Sections C and C’) are marked by a change from piano to forte. This disrupts my attention and causes a focal shift to the louder information. Contrarily, Section D (4:03) is significantly softer than the previous musical material, as evidenced in the wave-form. The difference in amplitude is abrupt which makes the already significant difference more salient for me. Additionally, gestalt boundaries at lower levels are also marked by noticeable fluctuations in volume. I have noted all the salient dynamic changes on the waveform in green lines connected to a rectangle in the middle of the waveform.

Saunders also uses dynamics as a textural tool. The illusion of musical depth which Jakubowski describes as, "one event continues in the background behind a more salient foreground event,” (2019, 220) is a common feature in phenomenological music, Section D in particular, and highly applicable to the visibility-to-audibility conceptualization of auditory fields. This phenomenon has been observed in Classical string quartets (Duane, 2016) and in auditory perception (Ihde, 2007). Interestingly, swell — McMullan-Glossop’s borrowed term from visual art — occurs, “[w]hen a sound gets gradually louder through a steady crescendo, the listener can not only perceive an increase in volume, but also an expansion in ‘colour’” (2017, 520 McMullan-Glossop’s spelling) prompting the thought that changes in certain parameters, such as dynamics and register, may be understood at least in part as novel timbre changes.

Similar to loudness, I hear timbral change when the register of an instrument changes. For instance at 3:47.5, the viola shifts register which is salient enough for me to separate that subsection from the rest of Section C. My attention is still focused on the essence of the temporal focus of Section C but I can sense a transition occurring, the register change easing me into leaving my temporal focus in search of a new one. Though register, like pitch, is easily measurable via the score, I suggest that an abrupt and therefore novel change in register (Proposition 2) is more salient than the recognition of any specific pitch-class relationships. Howland (2015) and Maler (2018) acknowledge register’s role in the structuring of music and Kozak (2017) identifies that changes in register can account for changes in attention and attributes its contribution to the creation of musical texture. I have noted salient register shifts of an octave or greater in Example 4 with pink lines connected to a circle in the middle of the waveform.

There are moments in the piece where my attention is partially diverted away from the temporal focus of a given auditory field. I refer to these temporal spans as subsections and they represent segmentation on a lower gestalt level. Sometimes these subsections are defined by a change in peripheral sound. For instance, section C, the first viola solo, is sub-segmented due the appearance of the flute, creating the subsection C1. My focus on the essence of the sonic object (beating double stops about G3) do not change, but the addition of the flute is a salient reintroduction to a familiar timbre. The novelty of the flute is still crucial to the listening experience since it affects my attention, yet I am able to push the flute into the periphery of my perception and maintain focus on the viola.

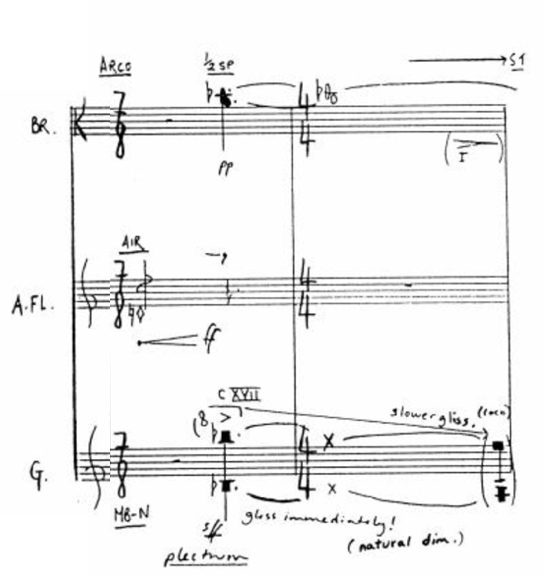

Other subsections are much more novel. For example, the upward composite glissando gesture in Example 7 is novel and different then the material that surrounds it. The surrounding material, however, is quite similar with a singular focus: the viola double stop between G/Ab. Perhaps more importantly, Example 7 is not long enough (or perhaps novel enough) to take my focus away from the essence of the sonic object. Even while listening to Example 7, I still anticipate the reappearance of the sonic object of section A. All other subsections, except Example 8 in section B, are moments where Saunders obscures my focus by introducing additional sonic information that I hear as peripheral:

⁃ percussive guitar hits in A,

⁃ flute long tones in B,

⁃ register change and reintroduction of the flute in C and,

⁃ heavy, loud bursts and the final glissando gesture in E

A listener with perfect pitch may understand why Example 8 is separated from section B since it shares pitch material with A, C, C’, and the final sonority. For me, however, this moment sounds like no other instrumental moment in the piece. The air of the flute and masking of the viola double stop entrance, in a new register, by the simultaneity of the percussive guitar sounds to me like an accordion. Even when looking at the visual information of the score and knowing how the trick is done, I still hear a new instrument. Like Example 7 however, Example 8 is bounded on either side by similar material, which is why I have opted to treat it as a subsection and not place it on the same gestalt level as other sections. It is worth noting that Example 8 is also one of two moments of B where the viola’s playing technique differs from the temporal focus: the viola bows the strings. The other arco moment is in a transitional section, B2, with material competing for my attention marked “Flute: long tones with gradations of fluttertongue.”

Discussion

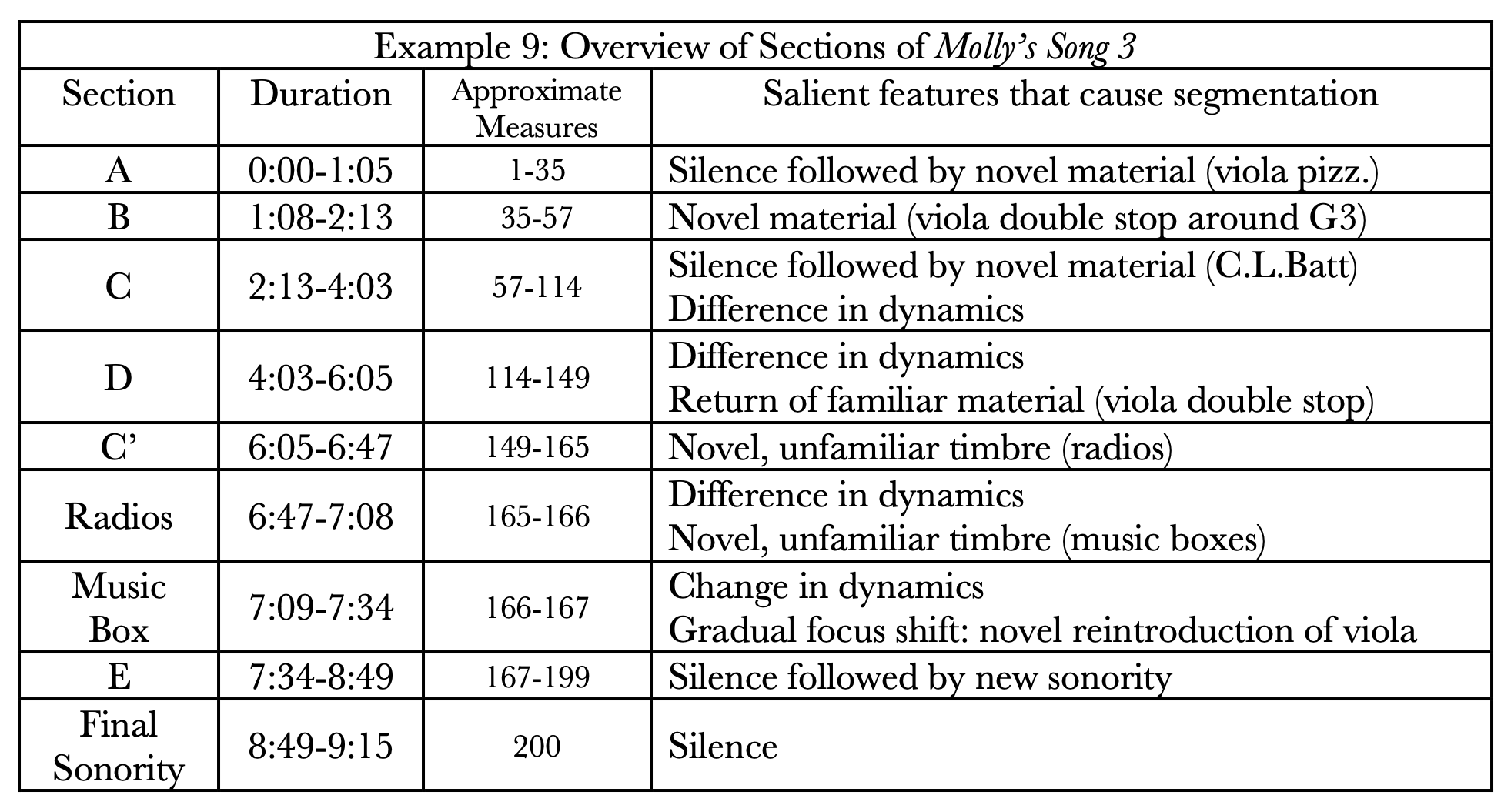

My visual analysis makes the boundaries I hear between sections clear. I have summarized the sections in Example 9 noting the approximate beginning and ending points of each section as well as the proposed causes of gestalt separation between sections.

These sections are products of my singular understanding of the piece, however, there are certain inherent features such as silence and novelty that make segmentation more likely for other listeners. In general, the salient changes that cause my attention to shift come from multiple parameters suggesting greater changes correspond with greater salience. As opposed to the score and pitch-based approach (Example 3), the focal cores of my analysis align with the viola playing techniques (Example 6).

The pitch-centric, score-based approach suggests there are more sectional boundaries than I propose. Some of the sections present in Example 3 are conceived of as subsections in Example 4. For instance, mm. 26-32 and mm. 32-34 in Example 3 correspond to subsection A2. Because the percussive guitar strumming is so prominent, I do not separate mm. 32-34 from the transitional strumming section. My attention is being drawn to the novel guitar technique though the viola has not changed enough for me to let go of the focal core. Additionally, mm. 51-54 and mm. 54-57 occur in subsection B2, however, these measures do not correspond to the peripheral material that grabbed my attention beginning with the entrance of the flute long tones in approximately measure 45. Lastly, the score-based approach suggests a hard division between mm. 167 and 168 whereas I am unable to pinpoint exactly when my attention shifts from the music box to instrumental playing. Though my method yields shares sectional boundaries with the pitch-based approach, it provides a simpler and more robust explanation of heard form.

My decision to include subsections in the visual diagram may imply that I am disregarding conventional “well-formedness” rules and the gestalt principle of continuity. My analysis conforms with the grouping well-formedness rules put forth by Lerdahl & Jackendoff (1983) with the exception of number 5: “If a group G1 contains a smaller group G2, then G1 must be exhaustively partitioned into smaller groups.” This final rule is not fully present in my visual analysis. My experience treats each subsection as a distinct gestalt with my attention being diverted to different material but returning to the material kept in my recent memory—retention at a nested hierarchical level. A subsection present in my analysis is a moment where my attention is temporarily diverted elsewhere as opposed to a gap where the temporal focus has completely disappeared from my consciousness. The reason I hear the two viola solos as different sections, as opposed to continuous, is due to the temporal distance between the two. Another analysis may hear moments I consider subsections as sections in new temporal spans and the return of material that follows a new temporal span. This interpretation would better reflect the aforementioned well-formedness rule.

The easiest section divisions to see on the visual analysis are the two separations due to silence; one that separates Sections A and B and the other that separates C and D. Additionally, sections B and D both begin with novel timbres and section D is significantly softer than section C. The division between section D and C’ is also visible due to the change in amplitude and contextually novel timbral material. While not apparent on the waveform, the timbral difference between C’ and the radios is impossible to ignore in the recording. The separation between the radios and music box due to dynamic change, however, is clearly visible in the waveform.

My visual analysis tends to show that one auditory field is replaced by another in a discrete sequence, rather than presenting overlapping fields or one field fading into the next through continuous gradual change. Consider the shift from Music Box to Section E. The music box is sounding throughout all of section E but the viola’s entrance from niente on F5 gradually distracts me. My attention shifts from the music box to the viola which becomes my temporal focus. This gradual transition is difficult to represent definitively in the analysis, so a dashed line has been placed between these two sections. This is similar to my experience listening to Section D. I hear both the col legno iterative object in the viola and the long tone objects in the guitar and flute as competing for my attention, both are focal and both are peripheral. I do not hear them as a fused entity but rather two different focal cores.

The separation between B and C is a bit more complex and requires additional explanation. Visually, it may appear that there is a significant separation just before the two-minute mark. I hear the flute shift register from a high, loud B5 to a soft B4 separated by a silence likely due to the flutist on the recording needing a moment to inhale. This moment fits the criteria to function as a sectional boundary, however, my focus is still awaiting the return of the pizzicato chords. It is possible that this moment will cause segmentation at the sectional level the next time I listen to the piece. In my experience, the similar timbre of the two flute registers, even with the color change due to the register shift, do not feel as different to one another as does to the viola double stop that occurs at 2:13. The viola double stop is further established as new material due to the silence that occurs at 2:23.5, a silence that encourages recollection and retention of the new auditory field. I continue to focus on the material that occurs after the silence which shares more of the essence of the viola double stop as opposed to any of the flute material.

The later portion of section B is the most complicated portion of the piece for me to segment. I lose focus as the percussive strumming sounds of the viola and guitar elides with the flute long tones with gradations of fluttertongue. Any perceptual boundaries between the percussive, noisy material and the continuous pitched material in the flute are not salient in my experience, contrary to the pitch-centric, score-based approach (Example 3). The boundary placed at 2:13 is the least salient sectional devision of the piece but is reinforced by aforementioned silence at 2:23.5.

Much of the discussion has been concerned with segmentation, but I am also actively grouping the material within sections into auditory fields. As I described in the section on phenomenology, my listening experience involves deconstructing the salient sonic material of each temporal span in an effort to find a thread of unity, the essence of the temporal focus of an auditory field. In this regard, I am applying gestalt principles as I listen for similarity, even if it is phenomenologically constructed in my imagination. The underlying assumption in my method is that the temporal focus will continue to be available to my consciousness. This is true for some temporal durations, but is not true for all temporal durations, especially as they grow longer. I suspect that my subjective attending can overcome some cognitive limitations but additional research on attention is required. A better understanding of listener attention is crucial to address this assumption and modify the shortcomings of my method accordingly.

Conclusion

I have argued and demonstrated that hearing form in “phenomenological music” requires listeners to group similar sounds together and intentionally attend to specific musical foci through imaginative variation while also noting significant changes based on salience to determine sectional boundaries. I have also put forth a new conceptualization of the auditory field with a focus on listener attention and temporality as opposed to an audibility/inaudibility dichotomy. Furthermore, I have proposed that there are specific criteria for music to be considered “phenomenological music.” Lastly, I have attempted to reconcile phenomenological approaches and gestalt theories of grouping and segmentation, however, I believe there is much more work to be done in this regard.

My analysis visually represents my experience at the section level. I have not attempted to quantify the strength of salience of any given musical feature or moment. Future analyses would benefit from an approach to approximating the inherent relative salience of a musical element or measuring the degree of change in a parameter. Any sort of quantification would still hinge upon the specific listener as salience is subjective (Proposition 4). Though accounting for listener differences in perception makes obtaining a measurement of salience more difficult, recent advances in real-time listening tasks provide the framework to begin measuring an average or median degree of salience of a given musical event.

Music theorists and musicologists are still faced with an absence of appropriate tools for the analysis of contemporary music, non-pitched music, non-notated music, and music from many different cultures. My approach is one way to open the door to consideration of contemporary music practices that challenge conventions such as the music of Rebecca Saunders. A question that remains open is how a listener copes with unfamiliar (and uncomfortable) sonic situations. The consequences of a listener’s inability to structure demanding and complex music may be a fruitful avenue for future music research across disciplines.

References

Adlington, R. (1999). The music of Rebecca Saunders: Into the sensuous world. The Musical Times, 140(1868), 48-56.

Alegant, B. (2013). A picture is worth a thousand words: road maps as analytical tools. Current Musicology, no. 95: 162.

Bailes, F., & Dean, R. T. (2007). Listener detection of segmentation in computer-generated sound: An exploratory experimental study. Journal of New Music Research, 36(2), 83-93.

Barash, A. (2002). Cadential gestures in post-tonal music : the constitution of cadences in messiaen's ile de feu i and boulez' premiere sonate, first movement [PhD dissertation, City University of New York]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Berlyne, D.E. 1971. Aesthetics and Psychobiology. The Century Psychology Series. Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Bregman, A. S. (1990). Auditory scene analysis : the perceptual organization of sound. MIT Press.

Bregman, A. S. (2005). Auditory Scene Analysis and the Role of Phenomenology in Experimental Psychology. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne, 46(1), 32–40.

Caplin, W. E. (2001). Classical form: A theory of formal functions for the instrumental music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. Oxford University Press.

Carlyon, R. P., Cusack, R., Foxton, J. M., & Robertson, I. H. (2001). Effects of attention and unilateral neglect on auditory stream segregation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 27(1), 115.

Clarke, E. F., & Krumhansl, C. L. (1990). Perceiving musical time. Music Perception, 7(3), 213-251.

Clifton, T. (1983). Music as Heard: A Study in Applied Phenomenology. New Haven: Yale University Press

Cone, E. T. (1968). The picture and the frame: the nature of musical form. Musical form and musical performance. New York: WW Norton, 11-31.

Davis, D. H. (2019) The Phenomenological Method. In Weiss, G., Murphy, A.V., & Salamon, G. (Eds.), 50 Concepts for a Critical Phenomenology. (1 ed., pp. 3–10). Evanston: Northwestern University Press. https://muse.jhu.edu/book/67156.

Deliège, I. (1989). A perceptual approach to contemporary musical forms. Contemporary Music Review, 4(1), 213-230.

Deutsch, D. (1999). Grouping mechanisms in music. In The psychology of music (pp. 299-348). Academic Press.

Dibben, N. (1999). The perception of structural stability in atonal music: The influence of salience, stability, horizontal motion, pitch commonality, and dissonance. Music Perception, 16(3), 265-294.

Dubiel, J. (2017). Music Analysis and Kinds of Hearing-As. Music Theory and Analysis (MTA), 4(2), 233-242.

Duane, B. (2016). Repetition and prominence: The probabilistic structure of melodic and non-melodic lines. Music Perception: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 34(2), 152-166.

Ellward, L. (2008). Rebecca Saunders Stirrings Still. Retrieved from http://heardaside.blogspot.com/2008/08/rebecca-saunders-stirrings-still-blaauw.html

Embree, L., & Mohanty, J. N. (1997). Introduction. In L. Embree, E. A. Behnke, D. Carr, J. C. Evans, J. Huertas-Jourda, J. J. Kockelmans, W. R. McKenna, A. Mickunas, J. N. Mohanty, T. M. Seebohm, & R. M. Zaner (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Phenomenology (Vol. 18). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-015-8881-2

Godøy, R. I. (1997). Formalization and epistemology. Scandinavian University Press.

Godøy, R. I. (2014). Ecological Constraints of Timescales, Production, and Perception in Temporal Experiences of Music: A Commentary on Kon (2014). Empirical Musicology Review, 9(3).

Godøy, R. I. (2019). Musical Shape Cognition. The Oxford Handbook of Sound and Imagination, Volume 2, 237.

Hanninen, D. A. (2012). A theory of music analysis: On segmentation and associative organization (Vol. 92). University Rochester Press.

Hasegawa, R. (2016). From Scratch: Writings in Music Theory by James Tenney. Computer Music Journal, 40(3), 83-86.

Hasty, C. (1981). Segmentation and process in post-tonal music. Music Theory Spectrum, 3, 54-73.

Helgeson, A. (2013). What is Phenomenological Music, and What Does It Have to Do with Salvatore Sciarrino?. Perspectives of New Music, 51(2), 4-36.

Howland, P. (2015). Formal structures in post-tonal music. Music Theory Spectrum, 37(1), 71-97.

Ihde, D. (2007). Listening and voice: Phenomenologies of sound. Suny Press.

Imberty, M. (1993). How do we perceive atonal music? Suggestions for a theoretical approach. Contemporary music review, 9(1-2), 325-337.

Jakubowski, J. R. (2019). Between Concept and Perception: Cognition, Experience, and Form in Spectral Music. [PhD dissertation, Washington University St. Louis] ProQuest Dissertations and Theses.

Kane, B. (2011). Excavating Lewin's “Phenomenology.” Music Theory Spectrum, 33(1), 27-36.

Kane, B. (2014). Sound Unseen: Acousmatic Sound in Theory and Practice. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 6 Mar. 2021, from https://oxford-universitypressscholarship-com.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199347841.001.0001/acprof-9780199347841.

Kozak, M. (2017). Experiencing Structure in Penderecki’s Threnody: Analysis, Ear-Training, and Musical Understanding. Music Theory Spectrum, 38(2), 200-217.

Kramer, J. D. (1988). The Time of Music : New Meanings, New Temporalities, New Listening Strategies. New York : London: Schirmer Books ; Collier Macmillan.

Lalitte, P., Bigand, E., Poulin-Charronnat, B., McAdams, S., Delbéé, C., & d'Adamo, D. (2004). The perceptual structure of thematic materials in The Angel of Death. Music Perception, 22(2), 265-296.

Lefkowitz, D. S., & Taavola, K. (2000). Segmentation in music: Generalizing a piece-sensitive approach. Journal of Music Theory, 44(1), 171-229.

Lerdahl, F. (1989). Atonal prolongational structure. Contemporary Music Review, 4(1), 65-87.

Lerdahl, F., & Jackendoff, R. (1983). A generative theory of tonal music. MIT Press.

Lewin, D. (1986). Music theory, phenomenology, and modes of perception. Music Perception, 3(4), 327-392.

Lochhead, J. (1980). Some musical applications of phenomenology. Indiana Theory Review, 3(3), 18-27.

Lochhead, J. (1982). The Temporal Structure of Recent Music: A Phenomenological Investigation. In Ph.D. Dissertation, State University of New York at Stony Brook.

Lochhead, J. (2006). “How Does It Work?”: Challenges to Analytic Explanation. Music Theory Spectrum, 28(2), 233-254.

Lochhead, J. (2016). Reconceiving structure in contemporary music: New tools in music theory and analysis (Vol. 2). Routledge.

Lochhead, J. (2019). Essay on Suzannah Clark and Alexander Rehding, eds., Music in Time: Phenomenology, Perception, Performance (Harvard University Press, 2016). Music Theory Online, 25(4).

Maler, A. (2018). Hearing Form in Post-tonal music. [PhD dissertation, University of Chicago]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Margulis, E. H. (2007a). Moved by Nothing: Listening to Musical Silence. Journal of Music Theory 51, no. 2: 245-76.

Margulis, E. H. (2007b). Silences in music are musical not silent: An exploratory study of context effects on the experience of musical pauses. Music Perception, 24(5), 485-506.

Margulis, E. H., & Beatty, A. P. (2008). Musical style, psychoaesthetics, and prospects for entropy as an analytic tool. Computer Music Journal, 32(4), 64-78.

McMullan-Glossop, E. (2017). Hues, Tints, Tones, and Shades: Timbre as Colour in the Music of Rebecca Saunders. Contemporary Music Review, 36(6), 488-529.

Metzer, D. (2006). Modern Silence. Journal of Musicology, 23(3), 331-374.

Miraglia, R. (1995). Influences of phenomenology: James Tenney's theory. Axiomathes, 6(2), 273-308.

Moran, D., & Cohen, J. (2012). The Husserl dictionary. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

Morrison, L. (2018). Strange yet Familiar Sounds in Zosha Di Castri’s String Quartet No. 1. Circuit: musiques contemporaines, 28(2), 83-98.

Nettingsmeier, J. (2012). Field Report II: A contemporary music recording in Higherorder Ambisonics. [Paper presentation] Linux Audio Conference, Stanford, CA, USA. Retrieved from https://stackingdwarves.net/public_stuff/linux_audio/lac2012/J%C3%B6rn_Nettingsmeier-Field_Report_II-Chroma-Screen.pdf

Pocknee, D. (2008). “Analysis of Rebecca Saunders's Molly’s Song 3 - Shades of Crimson.” Retrieved from http://davidpocknee.ricercata.org/writing/032_analysis_saunders-mollys-song/david-pocknee_analysis_rebecca-saunders-mollys-song.pdf

Ross, A. (2013). “Even the Score.” The New Yorker. Retrieved from https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2013/04/29/even-the-score

Saunders, J. (2004–2006). “Interview with Rebecca Saunders.” Retrieved from http://www.james-saunders.com/interview-with-rebecca-saunders/

Saunders, R. (2001). “Molly's Song 3 - Shades of Crimson.” Performed by Stefan Asbury & Musikfabrik NRW. Kairos.

Saunders, R. (2016a). Composition Class by Rebecca Saunders - VO (English) lecture [video]. Retrieved from https://medias.ircam.fr/x566dd1

Saunders, R. (2016b). Analysis : Fury II - English (VO) [Speech transcript by Evan Campbell] Retrieved from https://medias.ircam.fr/xa3ce1d

Service, T. (2012). A guide to Rebecca Saunders's music. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/music/tomserviceblog/2012/nov/05/rebecca-saunders-contemporary-music-guide.html

Smith, J. (2014). Explaining Listener Differences in the Perception of Musical Structure. [PhD dissertation, Queen Mary University London]. PQDT - UK & Ireland.

Steenhuisen, P. (2004). Interview with Helmut Lachenmann — Toronto, 2003. Contemporary Music Review, 23(3-4), 9–14.

Taher, C., Hasegawa, R., & McAdams, S. (2018). Effects of Musical Context on the Recognition of Musical Motives During Listening. Music Perception: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 36(1), 77-97.

Tenney, J (1964). _Meta (+) Hodos_. New Orleans, Inter-American Institute for Musical Research, Tulane University.

Tenney, J. (1985). “Review to Music as Heard by Thomas Clifton [Clifton 1983]” Journal of Music Theory 29, no. 1: 197-213.

Tenney, J., & Polansky, L. (1980). Temporal gestalt perception in music. Journal of Music Theory, 24(2), 205-241.

Thompson, S. K., Carlyon, R. P., & Cusack, R. (2011). An objective measurement of the build-up of auditory streaming and of its modulation by attention. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 37(4), 1253.

Tiits, K. (2002). On quantitative aspects of musical meaning. A model of emergent signification in time-ordered data sequence. [PhD dissertation. University of Helsinki.]

Uno, Y., & Hübscher, R. (1994). Temporal-Gestalt Segmentation-Extensions for Compound Monophonic and Simple Polyphonic Musical Contexts: Appl. to Works by Boulez, Cage, Xenakis, and Ligeti. In ICMC.

Uno, Y., & Hübscher R. (1995). “Temporal-Gestalt Segmentation: Polyphonic Extensions and Applications to Works by Boulez, Cage, Xenakis, Ligeti, and Babbitt.” Computers in Music Research 5: 1-37.

Zahavi, D. (2019). Phenomenology: The basics. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.