Musicians Auditory Perception (MAP) Interactive Project Report

Initial Project Report published February 1st, 2022

Updated peer-reviewed article published August 1st, 2022

Musicians Auditory Perception (MAP)

Listening and empathizing in the creative process

Interactive Project Report

Berk Schneider (University of California, San Diego) [Co-First Author], Florian Grond (McGill University) [Co-First Author], Jeanne Côté (McGill University), Pedram Diba (McGill University), Min Seok Peter Ko (UCSD), Sang Song (UCSD), Tiange Zhou (UCSD), Shahrokh Yadegari (UCSD) [Principal Investigator].

1. Overview

We believe that the creative process during musical collaboration is incredibly complex and awe-inspiring. While the analysis of music often focuses on structural and cognitive aspects, the remarkable bonds and friendships that may develop between musicians during the composition process is worth studying and understanding from an embodied and sensory perspective. The purpose of the Musician’s Auditory Perception (MAP) project is to collect qualitative data via sonic ethnography to promote and analyze: (a) auditory learning during sonic collaboration (i.e. an active musician’s ability to learn through listening), (b) modes of sound information gathering (via stereo and binaural audio recordings), and (c) the innate creative expression of musicians, while disrupting common pedagogic methods that reinforce hierarchical education and performance practices.

Auditory learning is not necessarily a linear process but a dynamic one that implies a skill set that is synergistic and deeply connected with creation. Therefore, MAP has enabled three student composer-performer duos from two Analysis, Creation, and Teaching of Orchestration (ACTOR) partner institutions, UC San Diego (UCSD) and McGill University (McGill), to document their collaborations while creating with binaural recording devices, adopting the concept of ‘sonic boundary objects’ — a concept first introduced in the context of blind ethnographies by Grond and Devos (2016). In our study, binaural recording devices serve as ‘boundary objects’ that help us negotiate between individual’s differing perspectives. We adapt ‘sonic boundary objects’ and their original use as a tool and practice that helps to understand and share the perspectives of individuals with different sensory skills and sensibilities. In the MAP project, ‘boundary objects’ are transferred to the field of music composition and performance and we apply them to nurture and understand the highly dynamic process between a performer and a composer during joint music-making. The overall outcome was that these ‘sonic boundary objects’ promoted skill-sharing among all participants by bridging differences in perception during the creation and reproduction of musical timbres. Specific to the situation of the COVID-19 pandemic, the application of binaural recordings has also allowed for a digital transfer of tacit knowledge by promoting an individual yet shared perspective during a challenging time to communicate for many artists. The following is a brief review and discussion on six months of collaborative work in the form of virtual meetings, creative output, and reflections. During this period, each composer-performer duo produced a musical score and recording while taking note of self-observations during the creative process.

2. Motivation & Method

The Musician’s Auditory Perception (MAP) Project arose from a curiosity in how contemporary musical performances are traditionally recorded by our technology as well as by our memories. While participating as students in the Composer-performer Research Ensembles (CORE) of the Analysis, Creation, and Teaching of Orchestration (ACTOR) Project, we realized that the complexity of the experimental music being composed and performed mandated qualitative approaches which emphasized first-person accounts during creative activities. What we found important was the potential ecological validity when it comes to studying timbre in orchestration, in turn framing the internal validity of the ACTOR Project’s many perceptual studies (e.g., Upham & McAdams, 2018).

In contemporary musical practices, the dichotomy between the composer and performer has somewhat softened. The intermediary-performer is not solely an interpreter in some indeterminate works by Cage or Feldman and is often eliminated altogether via technology in the music of electronic pioneers Babbit and Stockhausen. More recently, we find ourselves at a turning point in which both actors (performer and composer) engage as fellow creators. Much musical research in recent years has analyzed the relationships fostered among the improviser, performer, and composer (Denora, 2011; Foss, 1963; Lewis, 1996; Nooshin, 2003), and yet, it is still commonplace to think of Western music composition in a certain hierarchical light, seeing the composer as the creator and the performer as a player that plays out that creation. We see this issue problematized in spaces in which creative recognition is not negotiated, but rather given blindly to either actor and resolved in spaces in which creative practices are reflected upon and reevaluated accordingly, giving equitable air space to all creative participants.

In this light, we can understand musical improvisation as a way of knowing, in that improvisation puts less emphasis on the power dynamics between different actors, instead focusing on modes of shared experiences that fuel creative compositional practices. The MAP project documents these implicit or improvisatory behaviors via an online database of contextual interviews and surveys (Schneider et al., 2021), thus providing a framework for qualitative inference that can be used to understand complex relationships between its creative participants. This information, specifically the video recordings, can be used to heuristically evaluate the perception-action coupling that occurs when one is interacting with musical instruments over time (Goldman, 2016). This prescribed order of skills is often difficult to develop in the short term. A simple example is the correlation between vision and movement while playing an instrument. For example, the extended techniques a violinist may share with her collaborator are based on her ability to understand her movement over time and how her gestures may impact the timbre of the instrument. Unsurprisingly, both performers and composers have contrasting enactive perspectives (sensorimotor skills) that are required for their individual creation processes. In this situation, the performer has honed her skills through experience, offering tools with which to compose, while the composer may have a fresh stance and capability to hear things the performer has either forgotten or ignored due to her systematic habituation of skills over time.

In view of these complex interactions between the worlds of the composer and the performer, we developed our own roles, as musical collaborators, and tools, in the form of scores and taxonomies, adopting the concept of ‘sonic boundary objects’. Introduced first as binaural recordings in the context of disability ethnographies (Grond, 2016), analyzing boundary objects became a way to express and illuminate the invisible exchanges between creative individuals. This sensory approach based on listening presented itself as a natural fit for our investigation into the role of recordings and memories during collaborative musical creation, including how we gather and translate information during score construction as well as how timbral identification is used while playing musical instruments.

Given that all participants are practicing musicians, we chose a research-creation approach that focused on binaural recordings of varying acoustic contexts, amongst them an anechoic chamber, supporting the artists in their quest to reflect on their practice while working on their intimate creations. The research-creation approach is a good fit because artists not only hold specific knowledge related to their practice, but they also generate new knowledge as innovators and contribute to contemporary music through the development of new forms of artistic expression in performance and notation. By creating an inference space to enquire about our sonic perceptions during different points of the creative process it becomes possible to investigate how singular moments may inform the final composition. Through the creation of three collaborative scores, informed by each participant’s enactive experiences (such examples throughout this report are labeled Exp.) and correspondences (labeled CORR.), we enhance tacit knowledge structures that may assist timbral experimentation within equitable artistic milieus.

3. Composer-Performer Collaborative Summary

Jeanne Côté and Pedram Diba — Embodiment and Intimate Space

Jeanne Côté (violin) and Pedram Diba (composer) traded two very distinct sonic experiences during the first two weeks of the project. Pedram recorded the sound of heavy rainfall (Pedram, Exp. #1). Pedram noted that this recording led him to experiment with the sound of a coin spinning on a tabletop, which he felt was much more satisfying (Pedram, Exp. #2). Jeanne was carrying out experiments of her own. She recorded the sound of hot air squeaking through the fissures of pancake batter (Jeanne, Exp. #1), later imitating the sounds on her violin (Jeanne, Exp. #2). Pedram then began to experiment with audio equalization (EQ) on both of his recordings in an attempt to “take out the background noise” (CORR. #1). This experimentation aligned with the concept of space for Pedram. He was also interested in the perceived gestural quality of the coin. He used Reaper to add a gestural trajectory to the rotative sound of the coin. Finding this very interesting, he noted the listener can follow the discourse for two levels of rotation. According to him, all these experimentations aligned with the idea of spectromorphology — a term coined by Denis Smalley to describe how a perceived sonic footprint manifests itself in time, usually electroacoustic in nature (Smalley, 1986).

Influenced by Antinoo (1999) by Francesco Filidei (Magalhães, 1970), the duo focused on the idea of perceiving sound from the point of view of the performer, and they started to think about ways personal, “human born” sounds could be transferred to a listener (CORR. #2). Jeanne used the binaural microphones to record the movement of the violin (Jeanne, Exp. #3) and herself bowing her own hair (Jeanne, Exp. #4). The pair became focused on a theme of intimacy in enclosed spaces. They were interested in sounds that could be translated using binaural microphones—in other words, sounds that “put you in someone else’s body.” The duo combined the concepts of embodiment and intimate space into their collaborative composition As Close as Breath.

Berk Schneider and Sang Song — Sonic Memory in Spatial Environments

Berk Schneider (trombone) and Sang Song (composer) decided to focus on the theoretical concept of autobiographical memory instead of working directly with the sounds they sampled (CORR. #1, Berk Exp. #1). Sang shared his initial understanding of flashbulb memory, describing how active emotional valences associated with collective events, such as the 9/11 terrorist attack, allowed individuals to not only remember the main event, but the relatively insignificant ‘side-events’ which occurred synchronously. Berk took these concepts and decided to freely improvise using both ear-hook binaural and stereo microphones (Berk, Exp. #2 — binaural; Berk, Exp. #2 — stereo); Berk, Exp. #3 (binaural); Berk, Exp. #3 (stereo) . The two experimented with the binaural microphones in outdoor spaces. It was determined that Berk’s movements through space likely impacted Sang’s representation or memory of the holistic features of the acoustic environment (Berk, Exp. #4; Sang, Exp. #4; Video Exp. #4, stereo).

In post-reflection, Sang connects the seemingly implicit sounds augmented by the binaural samples to side-events. He describes these peripheral memories as “very mundane things that are not directly related to [an] event itself, and you retain [them]. . . what seems insignificant can be memorized as something very important. . . small things being elevated to a memorable thing” (CORR. #2). One particularly salient sonic memory in which Sang recalled falling acorns near his family’s village was (CORR. #3) especially powerful when read aloud while listening to his percussive binaural improvisations (Sang, Exp. #1). Along these lines, Sang became interested in two different versions of a Grimm Brothers’ fairy tale (CORR. #4). Berk and Sang continued their discussions of memory in musical space, composing a work entitled Anura.

Peter Ko and Tiange Zhou — Poetic Fragility and Private Experience

Peter Ko (cello) and Tiange Zhou (composer) took an experiential stance towards the technology in their first two weeks of collaboration. Tiange sent a few audiovisual samples to Peter, highlighting her trip from the United States to Germany. One sample included the roaring sounds of a jet plane from inside the cabin (Tiange, Exp. #1) and another featured the pastoral sounds of urban Germany (Tiange, Exp. #2). In the midst of the COVID-19 epidemic, Tiange noted that these contrasting experiences held a certain holistic fragility in her mind. She notes that she “realized, you know, [this] sort of system is very fragile. . . how could things we suppose are strong, also [be] fragile, so the [fragility] of the sound itself [is focused upon]” (CORR. #1).

This conversation inspired Peter to demonstrate what he perceived to be “fragile-stasis” by recording three variations of ponticello (Peter, Exp. #1; #2; #3). After receiving Peter’s sul ponticello samples, Tiange started “trying to translate” his “fragile sounds into notation” by filtering out what she perceived as the fundamentals, leaving only the skeletal overtones (CORR. #2). For Peter, Tiange’s “little filtering was actually quite interesting because it reflected a little closer to what I was hearing under my ear.” Peter noted that perhaps his stereo recording device captured the fundamentals more strongly, as compared to what he was hearing from his vantage point with binaurals—closer to the cello (Peter, Exp. #4). The pair developed this concept of poetic fragility into an open score for solo cello entitled To Become.

4. Results

Four Strategic Lenses:

Binaural technology was used as a tool for meta-learning, outlined by four strategic lenses: (1) a musician’s individual relationship with musical instruments; (2) a self-reflective binaural approach to the creative process; (3) a device for tacit knowledge exchange; and (4) intention via notation.

I. A Musician’s individual relationship with musical instruments

Binaural technology changed the way musicians listened to their instruments. Over the last six months, our experience together was an opportunity to investigate how we identify different ways of knowing within our musical practice. One of the project’s goals was to discover how the development of particular performance experiences facilitates particular interactions with musical instruments via improvised perception-action coupling—that is, how one’s behavior is regulated by one’s perception and action within an environment.

To see how this action-relevant information is developed and used to regulate movement, we can examine Jeanne and Pedram’s experiment with intimate gestures. Pedram’s interest in spectromorphology was combined with Jeanne’s interest in the musical mimicry of inanimate objects within her personal space. Both experiences derived from sensory experience in that the knowledge both musicians gained from interpreting how “certain movements affect certain perceptions, along with the knowledge of the environmental regularities that govern such a relationship” (Goldman, 2016, p. 11) (i.e., the structure of the instrument, inanimate object, and acoustics) allowed them to approach the production of spatialized timbre through fluid gestures, eventually adapting them for the violin. Interestingly, this movement-oriented approach provided more than a method for Jeanne and Pedram to interact with each other and their environment: it also changed the way they perceived their own actions and the instruments they used as interfaces to execute movements to produce sound.

It was noted by Pedram and Jeanne, for example, that after reflecting on their binaural recordings, they could hear a clear timbral distinction between the sounds of Jeanne bowing her hair and rubbing her fingers on the frame and body of the violin (Jeanne, Exp. #3). These otherwise “white noises” would have been indistinguishable in most acoustic spaces with stereo microphones, but they retained their distinct timbres after closer inspection with binaural microphones. Furthermore, the timbral difference between tapping the strings with the wooden part of the bow (col legno, battuto e tratto, Italian for “with the wood [being hit]”)—as opposed to different kinds of pizzicato (plucking the strings with the fingers)—could be heard clearly with the binaural microphones (Jeanne, Exp. #5). Breathing sounds and extended techniques behind the bridge also carried distinct timbral qualities (Jeanne, Exp. #6) when compared to traditional stereo recordings:

Recording so close to the musician allowed us to capture very delicate and naturally quiet sounds. Besides exploring mechanical sounds, I investigated various techniques like rubbing the strings against my hair, sliding my hands over the violin and blowing into the f-holes.

Because of Jeanne’s newfound awareness of timbral space, the physicality and general compositional approach to violin changed for Pedram. This was precisely because of the subtle timbres which had been made more audible by the binaural recordings (Pedram, Interview). Their decision to explore these sounds in an anechoic chamber furthered the violin’s timbral potential:

The first goal was to record various soft and delicate sounds on the violin that we had previously decided on. . . The space in the anechoic chamber allowed for these sounds to be captured without any sound coming from the outside of the performer’s intimate space (Pedram, Write-up).

Jeanne confirms the impact of binaural listening within the anechoic chamber on her practice:

This silent room allowed us to collect samples of ‘pure’ timbres without the interference of any other noises. My sensitivity to timbre has been continuously improving, especially since collaborating on ACTOR projects. This research project has led me to reflect more specifically on my own instrument’s timbre, and its variants, pertaining to my own perception and spatial positioning (Jeanne, Write-up).

According to Jeanne, “three gestures produced results unique to the performer (hair, skin, breath), which is why my colleague and I called them “intimate sounds.” This formulation of knowledge and the way it enabled the duo’s behavior when it came to composing a spatialized work for violin is strongly intertwined with the concept of ‘sonic boundary objects’ we wish to make visible.

Similarly, the intimacy of the cello’s timbre in space, specifically its overtones, were observed by Peter and Tiange with binaural technology. Something that surprised Peter was the perceptual qualities of sul ponticello, a technique in which the bow is kept near the bridge of the cello, thus “subverting the balance of overtones in the sound” by bringing out the “higher overtones of the fundamental’' pitch (Peter, Exp. #1; #2; #3). Peter found that the timbre of this extended technique would sound very different depending on the listener’s distance from the cello. During these sul ponticello experiments, Peter used his head as an equalizer (EQ) in order to balance the sounds he heard around him. When turning to his right the lower frequency overtones were more audible and left the higher frequencies more abundant—C, G, D, and A open strings. He developed a hypothesis that there would be “some sort of progression in terms of the EQ of the binaurals” (e.g., a panning of sound from left for the C string to right for the A string), but this turned out not to be the case. He then recorded himself with the binaural microphones and video at the same time (Peter, Exp. #4). To his surprise, Peter noticed that he had deeply ingrained habits in which he would slightly tilt his head in relation to the cello, ultimately changing the way in which he heard the overtones of each fundamental pitch. He confirmed this by listening to each binaural ear-hook microphone individually (i.e. left and right ears), noticing that small “transients, noises, chiffs'' such as sudden, short-lived bursts of upper harmonics in each cello string were sounding slightly differently, not only based on his cello technique, but on the position of his head: “I want to be able to hear myself and I want to be able to hear myself clearly so I position myself so I can hear in a balanced, clear way” (Peter, Interview). The sounds resulting from Peter moving his head can be heard thirty seconds into his binaural recording of To Become.

This intimate experimentation with timbre, that of Peter’s sul ponticello and Jeanne’s submission to the visceral noise pallet of the violin in the anechoic chamber, was complimented by Berk’s binaural observations related to sonic directionality on the trombone. For instance, Jeanne’s statement that “playing for my own ears turned out to be quite a challenge. Among other things, I had to resist the impulse to project far into the hall, which is normally a concern of mine” was similar to Berk’s initial reaction after listening to his first-person binaural recordings of the trombone: “everything was muffled, I felt like I was under water when I was listening to these binaural recordings. . . I wish I could extend my ears outside of my body. . . biologically adapt!” (CORR. #5). These sentiments, which were shared amongst all performance participants yet yielded different reactions, suggest ingrained performance habits that favor projecting sound outward to an audience.

For example, the awareness of sonic projection was complemented by involuntary or mechanical sounds made by each instrument. Some instrumental sounds were not ‘projected’ into a traditional stereo recording, but were otherwise audible with binaurality:

Given the close placement of the mics, these sounds came through so clearly on the playback it made me want to refine my playing in order to eliminate them. . . In a creative-research context such as this, it seemed wiser to take the time to explore these mechanical sounds than to work on polishing my sound, as I would for a concert performance. Our interest in these kinds of sounds led us to seek out others that might be produced in the same space (Jeanne, Write-up).

Peter also became more aware of the smaller “fragile nuanced parts of the sounds” that he gravitated towards, very much like Jeanne; however, interestingly, the “daily sounds” or environmental noise in his recordings were perceived as interruptions to his musical “meditation” (Peter, Interview). Peter goes on to say that “listening to binaural recordings made me really understand the importance of spatialization in terms of how we perceive timbre, how distance can change the character of a sound as certain transients of the sounds disappear after a certain distance” (Peter, Write-up).

Similar observations were made by Sang and Berk; however, because of the trombone’s innate sonic directionality, its reverberant quality in acoustic space, and lack thereof suitable recording spaces during the evolving Covid pandemic, the duo embraced environmental noise over softer, “intimate” or “fragile” sounds, utilizing the binaural microphones in San Diego’s city parks. This initial experimentation in acoustic space soon took turns in unexpected directions. While reviewing the recordings, the duo began noticing how the sound of the trombone, once the primary sonic gesture of intrigue, was fading into the background (Berk, Exp. #4; Sang, Exp. #4; Video Exp. #4, stereo). This was striking for Sang because he realized he was not listening to his memories per se, but a representative smörgåsbord of external stimuli that had allowed him to craft his memories (Meeting. #3):

Listening to the recordings made during that al fresco recording session afterwards. . . turned out to be revelatory: the binaural recordings so vividly captured everything that I either ignored or was simply unaware of during the recording session that it prompted me to question the role of memory in such a context (Sang, Write-up).

Berk also “found that the ear-hook binaural microphones were actually much more effective when used to record large soundscapes rather than the trombone sound alone,” revisiting memories in which “rainstorms and early morning strolls. . . [with] waking birds were captured beautifully.” To Berk, “these sonic time capsules, as I might call them, were very special in that my movement through space became the focal point, rather than the sound objects moving around me” (Berk, Write-up).

Thus, how the trombone’s timbres could be perceived differently—e.g., a timbral “dullness” or “brightness” based on the acoustic space the trombone inhabited, its directionality/movement in that space, and how it was recorded via technology—became important aspects in Sang and Berk’s collaborative efforts. The effect of space on the trombone’s timbre can be heard clearly in Berk’s early indoor improvisations (Berk, Exp. #2 — binaural; Berk, Exp. #2 — stereo); Berk, Exp. #3 (binaural); Berk, Exp. #3 (stereo) and outdoor park recordings (Berk, Exp. #4; Sang, Exp. #4; Video Exp. #4, stereo). In both environments, timbres can be heard differently, independent of the microphones being used, suggesting that the environment a performer inhabits has a deep impact on the timbral perception of their instruments.

II. A self-reflective binaural approach to the creative process

Binaural technology changed the way participants created music by giving them a chance to reflect on their individual and joint perceptions during collaboration. Two factors contributed to this outcome:

a) There was time/space to think and perceive before responding or reacting in real-time (we could call this an unavoidable deep listening exercise).

b) The collaborators had the opportunity to re-evaluate past interactions with other participants by sharing various documents on the Google Drive (Schneider et al., 2021), which enabled the participants to return to points where communication had been lost, if necessary.

During the course of the MAP Project, our focus on processes rather than products stimulated development of problem-solving and critical thinking skills that assist reflective practice during the creative process. The key mediator in each composer-performer pair appears to have been time and space: time and space (provided by the COVID-19 pandemic) allowed the participants to reflect on embodied sonic experiences on their own as well as with their collaborators. This process provided each participant not only an inner context of their creative process, style, and technique but also possibilities for further analysis of binaurally recorded dialogues. In cases where communication between participants needed to be reviewed, this possibility gave each participant the agency to re-experience and deduct meaning from their previous interactions. One example of this was Jeanne and Pedram’s sonic gestures which would have been very difficult to reproduce and orchestrate without reviewing the binaural and video recordings. Importantly, these gestures derived from these recordings. Making an effort to understand what is sensible to peers and collaborators is particularly important in this context, since the methods in which qualitative research may inform how individuals make sense of knowledge exchanges can have an immense impact on their own approach to education and self-expression.

For example, revisiting immersive first-person recordings and interviewing the participants throughout the course of the project helped us to identify significant moments of interactions between the parties ex-post through self-report, which allows the validation of data gathered through complementary approaches. The study thus provides both first-person binaural perspective and third-person binaural perspective. This setup complements a classic stereo mix and the experience from the performer’s perspective, providing insight into how both perspectives might inform the creative process. Florian’s mix of Anura alternates between the first-person binaural perspective of the trombonist, and shifts to a third-person binaural perspective of a dummy head that was wearing binaural microphones. This allows the listener to experience two sonic perspectives within one recording. Each prospective alludes to either the locus of the personality of the prince or the frog. Another example is the sonic perspective of Peter’s cello bow or Berk’s trombone tuning slide, which the performers acquired by attaching binaural microphones to their instruments (see Peter, Exp. #5).

Reconstructed experiences aided the creative process; Jeanne notes that Pedram had sent her spatial sounds, e.g. a penny rolling: “I was paying a lot of attention [to] the movement”. . . “dividing the sound, analyzing the sound,” but, for the sound of rain, “I was experiencing the space, imagining I was there, the feeling of how it looked, sensed, and the temperature.” She could sometimes hear the spectromorphology of a sound, as it evolved over time, a realization that compelled her to mimic the sounds using techniques she developed on the violin (Jeanne, Exp. #7, Jeanne, Exp. #8).

For Jeanne, it was important that “the process was very creative, open, fun and liberating,” as the goal to compose a work through the investigation of the binaural microphones as well as the soundworld they revealed was enriching: “In the beginning it was strange to call it research, because it seemed like there was something missing to call it research,” but in the end, “I uncovered sonic elements that I wouldn’t have otherwise” (Jeanne, Interview).

Furthermore, Jeanne said that the “use of binaural technology greatly contributed to the discovery of new timbres and to a new perspective on listening” (Jeanne, Write-up). She noted that:

When the microphones were [on] my ears, I played the role of both musician and audience member. . . Having this dual role within my own space and without an audience to act as intermediary, it felt as if I [was] working with raw material. I was therefore able to quickly adjust my playing, including my timbre, by reacting directly to the sound as I heard it (Jeanne, Write-up).

Pedram and Jeanne experimented in an anechoic chamber, concluding that “the binaural recordings of both the violin sounds and the [other] sounds captured during 15 minutes of silence (breathing, digestive sounds, swallowing and so forth), helped to intensify the intimate aspect of these sounds as well as giving a clear idea of the timbral quality of each sound for a listener listening from outside of that space” (Pedram, Write-up, Jeanne, Exp. #9).

This realization through self-reflection on binaural recordings helped the pair understand how differences in perception of timbres ultimately enriched their creative process:

This outside perspective from my colleague, who was interested in things I had not considered, encouraged me to further explore certain sounds. Our numerous exchanges of audio or visual material as well as our work sessions also helped me to clarify my thoughts and redefine my ideas and objectives so as to better communicate them to my peers (Jeanne, Write-up).

Self observations and correspondences such as these enabled the duo to foster a creative process, helping to develop innovative timbres that can be heard in their composition, As Close as Breath.

In contrast, Berk and Sang’s binaural experimentation in more reverberant spaces helped develop their creative intent to comment musically on a morphology of autobiographical memory, rather than on sound itself. Their solo trombone work reflects on two very contrasting perspectives within the story of the Frog Prince (CORR. #4):

Just as our literary mechanisms adapt and change over time in accordance with artistic milieus. . .our memories of sonic form and gestures shape-shift in an effort to remain relevant (Berk, Write-up).

These adaptations are communicated and preserved via Berk’s interpretation of Anura, which is subsequently augmented by Florian’s mixing of the two audio perspectives of the prince and the frog. This mixing reflects on the interindividual perspectives of the internal or external listener, furthering the narrative transformation of the frog into a prince:

In Brothers Grimm’s version of the Frog Prince story (entitled Frog King or Iron Henry), what transforms the annoyingly tenacious frog into a “prince with beautiful kind eyes” is the princess throwing the frog against the wall in a rage, with an apparent intent to kill it. What, then, happened to the kiss—and what about the modern proverb “You’ve got to kiss a lot of frogs before you can find your prince”? In his study on the topic, the paroemiologist and professor of German folklore Wolfgang Mieder concludes that the proverb “is not so much a reduction of the fairy tale but rather an imprecise allusion to or reminiscence of it” (Mieder, 2014). In other words, this relatively simple story of transformation has somehow been transmogrified in our collective memory (Sang, Write-up).

“Interindividual differences” in perception were also a source of inspiration for Peter and Tiange. These differences added “a large degree of subjectivity to timbral perception, since Tiange seemed to perceive overtone structures differently than me” (Peter, Write-up). Reviewing Tiange’s binaural recordings helped Peter understand what “the realities of binaural recording were” and how the recordings captured sound differently from what he heard under his ears:

I would sometimes need to modify slightly what I did in order for the effect to come across with the recording. At the same time, it also opened my ears to certain sounds and effects that I either took for granted or filtered out, which allowed me to notice and attune to them as I played in real life (Peter, Write-up).

For Peter, the research-creation design of MAP allowed for rigorous exploration of material to learn and understand conclusions that might support an initial hypothesis. He notes that he already does this in his daily preparation for performances, considering all possibilities and trying to view his own work somewhat objectively. For him, a certain level of scrutiny, involving binaurals or a particular objective that “explores a set of questions it might evoke” was important. Research, for Peter, thus gave Tiange’s composition a purpose and rigor through ownership by the artist. “Playing” with binaural microphones was the research portion of the project. The creation part of the project was the “learning process” that occurred through the “provided background” of that research. Thus, “in some ways [binaurals capture the] performer’s intention in a much more subtle and different way” when compared to traditional modes of sound information gathering (Peter, Write-up).

During the course of the project, Tiange took Peter’s lead, conducting experiments of her own that utilized Peter’s fragile timbres. She stated that through this experimentation with sound, it was important to avoid using all the sonic variables on a specific instrument. Instead, she decided to focus on one pitch, evaluating how it changes from different perspectives. Her reflection on Peter’s recordings greatly impacted her creative process. She noted that “sonic nuances” within a single sustained pitch produced with sul ponticello can be so “fragile” that it becomes less important to emphasize rhythm and more important to analyze the transformation of timbre and sound from one phrase to another. She stressed that Peter should not use a metronome in this context, instead reinforcing “a self-reliant time frame.” This approach gave Peter the ability to reflect on how he perceives time while a timbre is changing, providing many different trajectories: “I provide a playground for Peter, to try different timbres and then create a certain trajectory that he is going to pursue” (Tiange, Interview).

III. Technology as a device for tacit knowledge exchange

Binaural technology changed the way participants shared musical knowledge. Because the interpretation of the final compositions is embedded in the creative process, it was almost as if the perceptual boundary between composer and performer had been removed. The MAP Project’s learning model was based on internal elaboration, interaction, connectivity, and shared knowledge building, and this provided its members with several methods and tools to analyze timbral composition and performance practice. To the participants of the MAP Project, tacit knowledge exchange was as much about the technological equipment changing the way one listens as it was about the acoustic space, particular instruments, and participating musicians.

Binaural technology helped the composer-performer pairs by encouraging positive personal auditory habits in which listening intentions transformed musical practice, making these practices quasi-prescriptive. For example, through learning how to hear key differences among individual sonic perspectives, shared soundscapes, acoustic-studio recordings, personal embodied experiences, and re-constructions of remembered experiences, each duo had the opportunity to analyze timbral characteristics from a variety of perspectives. They embraced the agency of the binaural perspective and what it brought to the process, not just as a mediator, but also as a tool for creation.

We view the use of binaural audio as a tool to break down the phenomenological barrier between musical process and product, including the commonly held belief in the binary opposition between compositional practices and improvisation, where improvisation processes are seen as incomplete compositional products. The MAP Project provides evidence that movement between acts of improvisation and composition are dynamic, rather than linear. During our collaborations, performers and composers alike improvised at different points in the creation process. It is not clear, however, where these points begin and end, corroborating the view that efforts to distinguish improvisation and composition is as much a political question as one of intention and action (Lewis, 1996; Nooshin, 2003). It is our hope that, by reinforcing collective forms of agency, it will become easier to break with hierarchical norms that exacerbate the separation of creational roles within different musical milieus. Having said this, since the intimate exchanges of the MAP project provided for a safe place to exchange ideas our focus became one of intention and action in creation. The binaural medium of exchange influenced intention and action during the creation process in that it sought to do away with myths that sow perceptions of aloofness or lack of intention during the act of improvising, replacing these notions with clear evidence of intent and action. In this sense our organized improvisatory experimentation with binaural media was structured around an intent to better understand our actions during the creative process. This intent changed the way we composed and performed the music. This is evident in the fact that each final score illuminated the intimate exchanges between the composer/composer duos. Peter and Tiange’s score was left completely open, Jeanne and Pedram’s score bears traces of the performer in the musical clef, and Berk and Sang’s score included a fixed media version that made the performer’s perspective part of the artistic intent.

The trading of improvised iterations between composer and performer duos redefines our understanding of improvisation in the context of creation. Instead of examining structural novelty, freedom, and constraints (which are contextually driven), the MAP Project seeks methods to evaluate composition as a way of knowing via shared understanding (Goldman, 2016). In our case we are curious about how our individual experiences influence our work together. This curiosity connects with how musicians transmit knowledge sonically and via scores, written theory/texts on technique, including the dispositif that upholds this knowledge distribution. An instrumentalist, for instance, might describe how they create a timbre very differently than how they perform it, highlighting the separation of the physical apparatus required for performance and the embedded knowledge of how to maintain it. Fortunately, our use of binaural technology allowed each participant to grasp the unexplainable, if only momentarily, via enactive perception.

For instance, the participants all agreed that loud musicking at a distance was the least desirable way to utilize the binaural mics and that intimate sounds and soft gestures enhanced a sense of embodiment. Thus, binaural technology allowed each participant to experience these shared understandings rather than to rely on the interpretation of less immersive or static media such as written scores or traditional audio recordings alone:

During our initial audio/video exchange, Jeanne and I both had a shared interest in the quality of space that was captured via the binaural recordings. Considering this shared interest and the important role of space in perception of timbre, we concentrated our focus on the concept of space, more specifically, space as perceived by binaural recordings (Pedram, Write-up).

This observation of the intimacy of binaural listening is echoed by Jeanne:

Binaural recording technology allowed me to more easily understand the ideas Pedram was trying to convey. It specified the position of the subject so precisely that I felt as if I were in Pedram’s shoes. . .Listening to these intimate sounds created the feeling of not only possessing the musician’s ears, but of being in their skin (Jeanne, Write-up).

Furthermore, for Jeanne, it was “fun to imagine [herself] as another person” and to be “open to other’s ideas.” The use of the binaural devices changed the way she communicated with Pedram and other musicians. Because there was time to digest and brew on ideas before responding directly to a collaborator, Jeanne felt more empathetic towards her collaborator’s viewpoints (Jeanne, Interview).

This intersubjective experience was amplified in the anechoic chamber: “by turning the lights off, we hoped to make the listening even more sensitive to the human linked sounds that were already perceptibly amplified by the space of the anechoic chamber” (Pedram, Write-up). Pedram wanted to know if it would “be possible to translate [Jeanne’s] experience to the composition” (Pedram, Interview). It was here that Jeanne noticed a certain ambiguity between the feeling of her heart beating and the literal sound of it, and the two went about trying to turn this visceral experience into a notated score for violin and electronics.

Other participants shared similar observations. Peter noted that binaurality for him “is not as much about recreating the sensation. . . hearing a sound and looking to see it, rather what I find when I’m listening to binaural audio with headphones [is that] instead, I feel different regions of my body being activated in response to the binaurality. . . I feel a response physiologically at different points [around my head]” (Meeting. #4). These shared observations suggest a sense of embodiment rather than mere translation of sound via technology, which allows participants to communicate tacitly through ‘sonic boundary objects’ in ways that would not be possible verbally.

Furthermore, for Pedram, bodily sounds gave a certain intimacy to his collaboration with Jeanne. He felt very close to her, noting how the anechoic chamber helped make specific perceptual timbral similarities and differences between the two more evident: “we can have [two] open spaces with similar reverb, but we can still differentiate the different timbres between the two” (Pedram, Interview). In the anechoic chamber, however, the perceived timbre of the violin would be less dependent on its distance from its sonic source, meaning Pedram had a window into Jeanne’s intimate space. “When something is closer to us we hear higher partials and further lower partials are present” (Pedram, Interview). Thus, different perceptions of acoustic space were more translatable while using the technology:

After sharing ideas and discussing how we thought of space, we realized that we had some similarities as well as differences in regards to this concept. Some similarities were: space as a means to communicate timbres, distance of various sound sources, and size of the room the listener is put in (Pedram, Write-up).

The main differences between Pedram’s and Jeanne’s perspectives included the importance of movement and counterpoint of various sounds in space for Pedram and the personal space of the performer and the sounds that were perceived within this personal space for Jeanne. In order to make these perceptual differences audible in As Close as Breath, the duo went a step further:

With the help of Florian, we recorded impulse responses (Jeanne, Exp. #10) in the anechoic chamber to be able to recreate the close and intimate space of the anechoic chamber on specific sounds in the composition of the electronics portion of the piece (Pedram, Write-up).

This concept of space being translated between participants was also noted by Sang:

I would say one of the most salient features about binaural recordings is their vividness. . . While I remain a skeptic when it comes to the use of binaural technology in concert halls, there is no doubt that binaural technology has the potential to significantly enhance composer performer communications thanks to its ability to preserve a sonic event/environment in a vivid and palpable manner (Sang, Write-up).

Emphasizing his experience while listening to Berk’s binaural recordings, Sang stresses that because of the COVID situation, “we ended up turning inward” because it was not possible to interact in person and within public spaces. Sang noted, “the only options that I had were recording the things around me.” This was “something I didn’t really expect'' and it “added another dimension” to our friendship. The “vividness” of the binaural recordings “made me feel like I was being invited into his daily life” (Sang, Interview).

Berk shared similar sentiments:

I felt through using the technology we both developed a deeper understanding of how we operate as musical beings. Binaural technology acted not only as a bridge between our perceptions of sound, but perhaps, more importantly, served as the catalyst that helped drive our interest in memory from a theoretical/intellectual viewpoint. This connection helps me convey more meaning through his musical form which in turn, I hope, engages the listener in a meaningful way (Berk, Write-up).

Regarding his collaborative relationship with Tiange, Peter said:

Binaural listening framed the approach of how we decided to form the concept of the piece. We felt that it represented an opportunity to explore an unusual level of perspectival intimacy in regards to sound, which involved a lot of discussion in trying to understand how the other partner perceived sound from their own perspective, rather than the typical mode of listening that focused on how sound would be projected in a more standard, “objective” sense (Peter, Write-up).

These statements suggest that binaural technology increased a feeling of connection within composer-performer pairs while playing a critical role in the development of their scores. Peter describes these moments of shared tacit knowledge as “agreements on listening.” For him, there was an objective mode of listening and a subjective (binaural) mode of listening when it came to timbre descriptors: “Tiange and I hear things a little differently; I get the impression that she hears overtone structures a little differently than I do.” For this reason, their collaborative process was not a stereotypical composer-performer relationship in which a performer judiciously polishes the finished score and performs it. It was more of a hands-on approach, which Peter labeled “old fashioned” or “baroque style.” Peter notes, “composition would only dictate so much, and the rest was decided by the performer’s intuition, improvisation, and ornamentation.” He states, “we worked a lot collaboratively like that.” The binaural technology thus assisted in their endeavor to develop a lexicon of timbral vocabulary pertaining to sul pont.

In addition, working closely with Peter also motivated Tiange to learn a musical instrument. Her work with sul ponticello had made her sensitive to the many intricate layers of a cello’s timbre and she began learning subtle finger movements on the djembe, stating excitedly: “I’m sitting too much in front of the desk. I need to be more on the stage!” (Tiange, Interview).

In this context, the MAP experiments continued to unravel nonsensical divisions between composers and performers, a perceived binary relationship that has long been discussed (e.g., Foss, 1963). Binaural technology did this by providing for an immersive sonic perspective: the binaural microphones allowed musicians to embody one another, creating an experience of oneness with the collaborator. In addition, the technology itself seemed to demystify each participant’s approach to the act of performing and composing, making these acts intersubjective experiences.

We believe this integration of musical structures at varying levels of abstraction helps train our minds to be sensitive to differences in perceptual processes. If perception of timbre irregularities is in fact trainable via improvisation (Vuust et al., 2012), we can hypothesize that differing perceptions can also be intersubjectively learned via immersive binaural audio. This shift in perception is visible while playing back a participant’s process (whether it be performance-based or compositional), the binaural audio and video material, although not carbon copies of the original experience, eliminate certain barriers between participants. We can see this metaphorically and literally when analyzing timbres within space. Timbres resonate through time, and reverberate on, off, through, and across global ecologies.

IV. Intention via Notation

By giving a literal voice to each participant, the MAP Project breaks down two critical areas of interpretation—sound-to-text and the return from text-to-sound—thereby clearing many assumptions or misconceptions regarding the affect of timbre by the observed and the projected affect made by the observer.

Through this intention to communicate via binaural technology, participating composers became comfortable sharing their compositional processes as well as their musical intentions through notation. The MAP project, accordingly, can be thought of as a meta-composition in its own right, in that it derives from self-reflection on the structures of each participant’s individual creative processes. The documented communication between the members of each composer-performer pair as well as among the entire group represents collections of meaningful events that we can look back on and develop an aesthetic connection with (Schneider et al., 2021).

This approach changed the way participating composers addressed ownership of their final compositions. In Tiange’s case, this meant listing Peter as a co-composer of their work for cello, To Become. For her, during their process of collaboration, Peter had contributed to core ideas of the composition, and she believed that they should share the copyright of the piece. This belief is reflected in her notation, an openly notated graphic score that puts importance on intersubjective relationships:

Open as an adjective means allowing access, passage, or a view through space; not closed or blocked. If used as a verb, it means moving or adjusting to leaving a space allowing access and view. Therefore, it has to be comprehended into two different viewing angles. Beyond the specific composer-performer relationship in an "open" situation, an open score is an artistic format containing indeterminate aspects or dimensions, which provide opportunities to achieve the transformable morphologies of musical continuity (Tiange, Write-up).

For Tiange, this meant that Peter was a creative participant in score creation rather than merely a performer playing passively through the composer’s will alone. Many aspects of Tiange’s musical experimentation are based on a flexible continuum or accumulation of music knowledge that was shared over the course of the project (Tiange, Interview). In this sense, the score of To Become carries a certain plasticity, adapting the traditional context of a musical score that carries its influence from a specific source (i.e., Peter’s playing of a single tone) by returning to that source to be reinterpreted in an indeterminate way by the performer and their enactive perception:

The open score composition based upon one fundamental pitch [diminishes] the parameter variables. For experimental purposes, this [approach] would help me quickly [review] the recordings from the workshopping sessions with the collaborating cello player Peter Ko to make reliable choices and organizations among all possible sonic phenomenons. . . Focusing on listening to small and fragile timbre transformations is the key to this experimental piece. Creating a time flexible zone is critical for performers to approach the sound one tends to achieve slowly. Therefore, in this piece, the duration markers depend on the performer's perception instead of the absolute time (Tiange, Write-up).

To Become takes sul pont, on the open G string, to an extreme, displaying how the performer can to some extent influence which partials are brought out. The first three sections outline a progression that gradually works towards higher partials, sometimes at the complete suppression of the fundamental. Peter’s ordering of the “trajectory options” are shown in red above (<Ex. 1>). The important thing to note here is that these variations in timbre are accomplished solely through the bow alone, with no influence from the left hand.

The following sections thereafter feature the left hand working in various ways to indirectly influence the sul pont tone, by plucking notes on other strings and influencing other points of sympathetic resonance. Furthermore, by weakening the fundamental and emphasizing higher partials with sul pont Peter primes the listener’s ear so it can be more sensitive to the individual timbres that make up each distinct tone on the cello. We eventually return home, to a more conventional cello tone, but now with the knowledge and experience of having explored the different parts of the instrument’s resonance. Much like how a chord in a string quartet is made up of many individual tones (played by four string instruments), Peter’s single tones are composed of an overtone series that can be separated by a trained ear. These parts comprise its whole, thus the parts become the perceived whole.

Likewise, Pedram and Jeanne felt that their collaboration during the course of the project had an immense effect on their composition, As Close as Breath. “To give material to a composer” they “developed a theme”. “The ideas were so strong, that clearly there were things we exchanged before that were going to be there” (Jeanne, Interview). Jeanne notes that this preparation, leading into Pedram’s experimental notation, made things much more accessible during performance. The collaboration process thus fed into a certain readability of the score (Jeanne, Interview).

Pedram’s composition practices came from experimentation with electro-acoustic ideas of EQ:

As a composer, I am always interested in [the] timbral qualities of sounds in my listening. These timbral qualities could be shaped from various parameters such as harmony, morphological shapes, energetic distribution between the components of a sound, orchestration, and so forth (Pedram, Write-up).

In an effort to explore the very subtle, soft, and delicate noises of Jeanne’s violin, Pedram designed his electro-acoustic composition to reflect the intimate space of a performer:

As Close as Breath a piece for amplified violin (with binaural microphones) and electronics written for this project, explores the ideas that Jeanne and I experimented with. The title of the piece refers to being so close to someone that you feel the blow of their breath. This touches on the closeness of the space as well as the intimate aspect of it. Additionally, the last thing the performer does is [breathe] into the f hole of the violin (<Ex. 2>):

Ex. 2: As Close As Breath mm. 61-63

The score is for digital audio track and violin. Pedram notes that for the instrumental part, he used several sounds that the duo explored in the anechoic chamber:

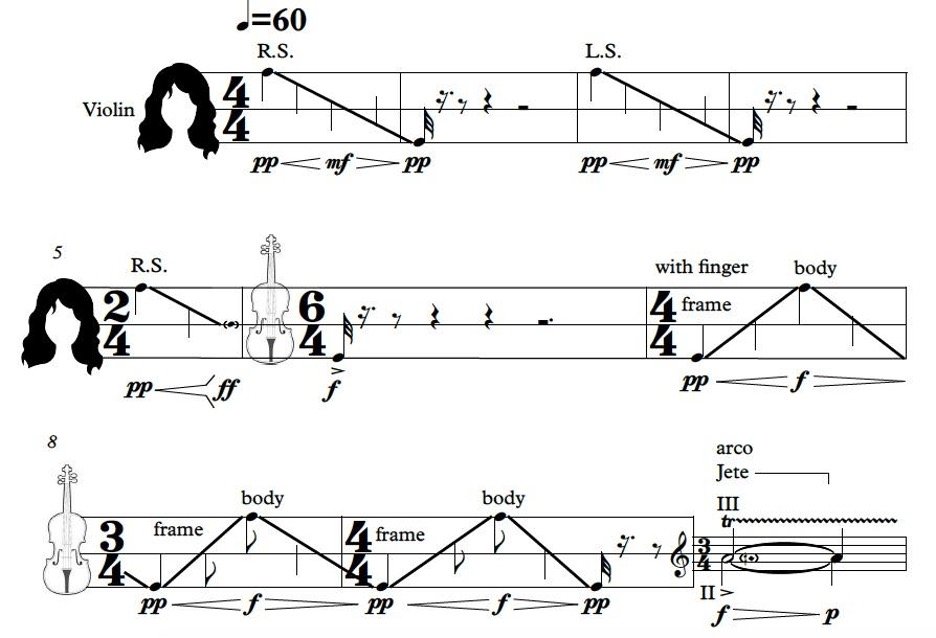

The use of binaural recordings helped me understand each sound’s characters and timbral qualities. As a result, I was able to put these sounds into musical time and discourse to create a cohesive formal structure. A lot of these sounds redefine the performer’s relationship with the instrument in the way that they are produced, therefore, an efficient system of notation is necessary to communicate these ideas. During one of our conversations, Jeanne explained to me that the hair has three main timbral regions (the top, the middle, and the bottom). This gave me the idea of creating a clef in the shape of a head and a 3 lined musical system where each line represents one of the timbral territories. For the other sounds explored on the body and fingerboard of the violin, I used a violin clef similar to the one Helmut Lachenmann uses in Pression (Pedram, Write-up) (<Ex. 3>).

Ex. 3: As Close As Breath, mm. 1–10

Jeanne discusses the motivation and challenges of the notation:

All of the conversations and ideas that emerged over the course of this research project resulted in a work that employs the musician’s inhabited space, movements, and personal sounds. The piece is written for amplified violin with binaural microphones and is accompanied by a digital audio track. Some logistical adaptations had to be made; since it is impossible to wear both mics and headphones, I will have to play without hearing the track. A graphic score, a visual metronome, or both may solve this problem (Jeanne, Write-up).

The piece was later recorded using a Max patch that embedded a visual metronome into the score. Jeanne played along with this metronome, which was synchronized with the digital audio track (<Ex. 4>):

MAP also impacted the compositional intent of Sang’s notation, but from a different trajectory. Berk reflects on how his experimentation with binaural listening may have influenced the scheme for Anura:

Binaural listening made me aware of Sang’s intent to communicate musical ideas about

memory. . . These gestures are performed as isolated motifs in a quasi-tone painting style and thus provide for a programmatic compositional approach to the original Brothers Grimm’s “The Frog King” and “Iron Heinrich” stories. . . It seems to me that Sang’s compositional intent is less built from the technology itself, rather the binaural technology serves to support a premeditated-theoretical approach within his compositional practice. That is to say, we were curious about the way binaural technology [changes the way we remember]. . .Therefore, by performing the musical form as accurately as possible the concepts of memory adopted from our experiments with binaural technology take shape [within the score] (Berk, Write-up).

Describing his creative intent, Sang notes:

In Anura, the frog’s transformation into the prince takes the form of two musical threads that were originally fused to form the frog’s annoying croaking gradually being separated as the music’s transformational process unfolds. In reflection of the multiple stages of a frog’s metamorphosis, this process takes place in discrete stages—and, in the end, the thread representing the frog vanishes and only the thread representing the prince is left behind (Sang, Write-up).

Sang states that within binaural recordings, you hear two “streams” or “rhythms” in either ear—our auditory cortex naturally processes a composite of both streams. However, while reflecting on binaural technology, these streams appear more separate. Anura is made of these two streams of sound, one stream representing the frog and the other the prince. By adopting concepts from experiments by McAdams (e.g., 1979) to bifurcate two streams of sound, Sang introduces an interesting parameter to his composition: “one potential way of realizing this piece is by assigning one stream to one ear and the other to the other ear,” thus bringing out the bifurcation (Sang, Interview #2 ). This approach introduces a challenge that is difficult to realize in a concert hall setting. Sang mentions that a trombone player could play the “frog notes” in one microphone and only the “prince notes” in another microphone, combining them later in a recording (Sang, Interview #2). Florian was able to artificially produce this effect within Anura. In the Leggiero section, Florian crossfades between the binaural microphones, starting from Berk’s perspective, slowly shifting to an external third person perspective (<Ex. 5>):

Ex. 5: Anura mm. 64-79

These streams gradually become more distinct throughout the composition as the frog stream disappears and the prince stream remains. The grotesque metamorphosis is represented by discrete motifs which are further illustrated by the annoying quarter-note E♭s (serving as the frog’s initial croaking), falling microtonally, until completely pulling apart into larger, more ambiguous intervals. In the middle section of the work, however, lyrical phrases longingly pause to reflect on Meider’s proverb (Meider, 204). Not only do spatial effects provide contrast between the muted microtonal upper register (frog) and more prominent diatonic low register (prince), but they also accentuate the distinct characteristics of each binaural ear-hook microphone, which capture the performer's perspective (Berk’s) in addition to a listener’s (third person). Although these natural acoustical differences are apparent in Anura’s Elegantly section, mm. 95-110 (Berk, Exp. #4; vs. third-person Exp. #4), this effect is even more prominent in the final Steady section in which the frog and prince “streams” become increasingly distinct. Florian’s spatialization situates the lower stream of the prince in the forefront by the end of the piece, thus making the frog’s transformation complete (See Ex. 6):

Ex. 6: Anura mm. 112-127

5. Conclusion and Future Research

The forms of attuned listening learned from MAP’s experiments have assisted in uncovering the subtleties of creation, translation, and reproduction, while mapping them over plausible semiotic representations in composition. This has not only helped the participants to discover their own roles in musical creation, but also to sort out timbre’s enigmatic courtship with the idiomatics of instrumental writing. Each participant moved fluidly between the role of composer and performer, helping to transform this traditionally dichotomous relationship into a dynamic spectrum-based model of creative exchange. In this non-hierarchical space improvisatory methods for timbral production helped foster collaborative auditory education and the training of inquisitive contemporary musicians. Based on the positive experiences we gathered, the study serves as a pilot evaluation of the potentialities for binaural recordings in ethnographic research related to adolescent music education and improvisation — a method to unlock the creative potential of all young performers and composers.

While the sonic boundary object approach channeled differences in perception and concerns between the musicians and the composers in a highly productive research-creation project, it would be interesting to uncover methods in which our individual perceptions of timbre could be further measured, while drawing the relevant connections between this study. Could we uncover how voluntary forms of attention on timbral events might be informed by implicit — or ‘background’ — semi-activation in the brain via bottom-up processing? It is clear that we can use binaural technology to test the processing time for the recognition of target timbres and see if these timbres can be readily ignored or attended to in the context of space using mismatch negativity (MMN). Visual and sonic paradigms already exist (see Czigler & Winkler, 2010; Siedenburg, 2019; Vuust et al., 2012), but we are unaware of any study that focuses on timbres and the relative position of the musician to her instrument. The goal would be to create a quasi-lexicon that organizes spatial timbre identifiers such as closeness, surrounding, movement, density, depth, surface, giving composers more control over the creative parameters of spatial (dis)orientation while eliciting complex responses from the listener. Furthermore, Individual Head Related Transfer Function (HRTF) modeling would complement each participant’s account of timbral experience, helping to determine how spatialized timbres interact with anatomical features, such as the shape of our head, cavum conchae, shoulders, torso, as well as the direction of a sound source and its environmental acoustics. The results could be very profound when analyzed in conjunction with the thick qualitative data we have accumulated here.

MAP’s foremost objective is to continue to provide ACTOR members affected by the new situation for the performing arts due to the COVID-19 pandemic with an outlet for creation. We believe that this new situation creates a moment for reflection on habits and practice amongst musicians which in turn is an opportunity for research. It is our hope that as we transition out of pandemic times and return to in-person performances, that our binaural ethnographic work on the musician’s position, her relation to the instrument and environmental acoustics and the resulting timbral relationships can be further studied.

6. Media

Scores

Recordings

References

Czigler I., & Winkler I. (2010). In search for auditory object representations. Unconscious memory representations in perception: processes and mechanisms in the brain (pp. 71–99). essay, John Benjamins Pub. Co.

DeNora. (2011). Music-in-action: Selected essays in sonic ecology. Ashgate.

Foss, L. (1963). The changing composer-performer relationship: A monologue and a dialogue. Perspectives of New Music, 1(2), 45–53. https://doi.org/10.2307/832102

Goldman, A. J. (2016). Improvisation as a Way of Knowing. Music Theory Online, 22(4). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.22.4.2

Grond, F., & Devos, P. (2016). Sonic boundary objects: Negotiating disability, technology and simulation. Digital Creativity, 27(4), 334-346. doi:10.1080/14626268.2016.1250012

Lewis, G. E. (1996). Improvised music after 1950: Afrological and eurological perspectives. Black Music Research Journal, 16(1), 91-122. https://doi.org/10.2307/779379

Magalhaes, M. A. (1970, March 2). Francesco Filidei : Gestualité Instrumentale, Gestualité Musicale. Gestes, instruments, notations. Retrieved January 8, 2022, from https://geste.hypotheses.org/231

McAdams, S., & Bregman, A. (1979). Hearing Musical Streams. Computer Music Journal, 3(4), 26–60. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4617866

Nooshin, L. (2003). Improvisation as ‘other’: Creativity, knowledge and power – the case of Iranian classical music. Journal of the Royal Musical Association, 128(2), 242–296. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrma/128.2.242

Schneider, B. W., Côté, J., Diba, P., Grond, F., Ko, P., Song, S., & Zhou, T. (2021). Musician's Auditory Perspective Project: Administrative Meetings, Final Compositions and Write-ups, Final Interviews, Group Meetings, Headshots, Misc Correspondence, Shared Photos & Video Files, Shared Sonic Files, Tritone Paradox, Google Drive.

Siedenburg, K., Saitis, C., Popper, A. N., Fay, R. R., & McAdams, S. (2019). Timbre: Acoustics, perception and cognition. Springer.

Smalley, D. (1997). Spectromorphology: Explaining sound-shapes. Organised Sound, 2(2), 107-126. doi:10.1017/s1355771897009059

Upham, F., & McAdams, S. (2018). Activity analysis and coordination in continuous responses to music. Music Perception, 35(3), 253–294. https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2018.35.3.253

Vuust, P., Brattico, E., Seppänen, M., Näätänen, R., & Tervaniemi, M. (2012). The sound of music: Differentiating musicians using a fast, musical multi-feature mismatch negativity paradigm. Neuropsychologia, 50(7), 1432–1443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.02.028

Mieder, W. (2014). “You have to kiss a lot of frogs (toads) before you meet your handsome prince”: From fairy-tale motif to modern proverb. Marvels & Tales, 28(1), 104-126. doi:10.13110/marvelstales.28.1.0104