En s’effaçant Jonas Regnier

En s'effaçant

Written for the Quasar Saxophone Quartet

Composer: Jonas Regnier

Performers: Quasar Saxophone Quartet: Marie-Chantal Leclair, Soprano Saxophone; Mathieu Leclair, Alto Saxophone; André Leroux, Tenor Saxophone; Jean-Marc Bouchard, Baritone Saxophone.

Introduction

This research-creation project, organized by the ACTOR Project, focuses on writing a 10-minute composition for the Quatuor Quasar (a saxophone quartet based in Montréal), using one soprano saxophone, one alto saxophone, one tenor saxophone and one baritone saxophone. The composition should focus on using and blending saxophone multiphonics together. All composers were asked to take notes during the composition process. A total of three workshops were organized in the Montréal studios of the Quatuor Quasar from September 2023 to March 2024, to explore preliminary sketches and ideas from each composer involved in the project.

I. Composition Ideas and Concepts

As I considered concepts related to multiphonics for this research-creation project, the idea of animal camouflage (such as done by the chameleon or the cuttlefish) emerged as a pertinent metaphor for these bizarre yet fascinating sounds. The notion that multiphonics can serve as a musical equivalent to colour camouflage resonated with me for several reasons: (1) portions of the pitch content of multiphonics can be either inaudible or exceptionally quiet to the listener, (2) although the creation of multiphonics is a subtle process, they can emerge quickly from a single note and create a surprising effect, (3) just as camouflaging often involves textures on top of colours to blend in with the environment, multiphonics often carry within them a very particular “textural signature,” which gives them a specific identity. I used this concept of camouflage to generate the perceived form of the piece (“esthesic aspect[1],” Nattiez 1990). I aimed to accomplish this musical camouflage metaphor by contrasting two distinct perceptual spaces: a small space featuring loud, textured sounds symbolizing a chameleon, and a large space with soft, smooth sounds representing the chameleon's surrounding environment. The opposition of the two spaces was established either by transitioning from one space to another abruptly, by transitioning progressively, or by juxtaposing them directly within the ensemble.

The second cross-modal concept I used in this piece is “petrichor.” Petrichor is the scientific name given to the unique earthy smell associated with rain once the raindrops hit the ground. I drew upon the chemical properties and origins of petrichor to shape the internal structure of the composition (“poietic aspect[2],” Nattiez 1990). The petrichor smell comes from three different components. The first is the presence of ozone in the rain droplets due to lightning strikes splitting molecules of nitrogen and oxygen into molecules of nitric oxide and ozone. This process was depicted musically through a violent contrast between a loud, complex, and heterogenic texture and a quiet, simple blended mass (usually in unison). This contrast is exploited in the piece in sections 1 and 6. The second component of petrichor involves the release of a bacteria called geosmin from the soil into the air by raindrops. Geosmin can be detected by the human nose in very small quantities. I explored this idea in sections 3 and 4 of the piece through gestural (i.e, less textural) materials. The last component of petrichor comes from the release of plant oils into the air when it rains. I metaphorically translated this idea into music in sections 2 and 5, using semi-textural and semi-gestural materials. These two sections contain sudden accents, fast ascending movements and a more sustained polyphonic content.

I endeavoured to evoke both the esthesic and the poietic aspects of this piece in the program notes by writing a short poem that metaphorically refers to some of the elements mentioned above:

En s’effaçant

Au creux du bleu

Dans la bouche de l’ozone métabolique

Disparaître

Renaître, au milieu du vert

Sur une branche fanée – grimpant

Sur les multiples cimes subtiles

Laissant derrière le vide camouflé

Retrouver le rouge – effacer l’azur

II. Experience with Workshops

Having previously composed several pieces for saxophone and explored most of the contemporary techniques and timbral possibilities of the instrument, many of my questions during the workshops concerned the dynamic and timbral balance between the instruments. Most of these questions were answered by the Quatuor Quasar during the workshops. In my opinion, one of the biggest challenges in writing for a saxophone quartet is understanding the timbral specificities of each saxophone to create a balanced mix, so that the sound resulting from the combination of four saxophones ensures that no saxophone gets masked[3] by the others. Being able to achieve this balanced mix between all four saxophones is necessary for composers who seek to create perceptually blended effects in their music. This blend can be obtained when the perceived dynamics of all saxophones are equal or balanced. One of the biggest difficulties with wind instruments, particularly saxophones, is that the timbre and the minimum/maximum possible dynamics of each instrument vary greatly depending on the register of the pitch being played. Since timbre represents one of the most important materials and parameters in my music, it was necessary for me to first learn how to orchestrate sounds, including multiphonics, in a saxophone quartet.

Some questions I came up with during the workshops concerned saxophone orchestration techniques: which multiphonics work better together? Do multiphonics blend better if they have the same fundamental, a similar harmonic spectrum content, or the same overall texture? How can one achieve a blend between the four saxophones if they all play in different registers? Would the baritone saxophone overpower other saxophones most of the time because of its specific timbre, texture, and loudness?

I learned that texture plays a major role in achieving a multiphonic blend (much more than pitches or even registers). I also learned which dynamics are possible in all registers of each saxophone: the most important information to retain is that quiet dynamics are impossible in the very low register of all saxophones. Lastly, the baritone saxophone’s timbre can be easily blended with the other saxophones when playing in its medium or high register. Its low register could also be used to obtain a concurrent blend if the other saxophones play very grainy, textural, and loud sounds.

The edits that I made in my musical materials as a result of the workshops were mostly orchestration changes (dynamics, articulations, etc.) and formal changes (general form of the piece, length of each section, discourse, etc.). During the workshops, I realized that most of my ideas were a bit underdeveloped and could benefit from being extended to make the materials sound more organic and coherent. It also helped me to learn more about the perceptual effects of the materials I wrote, and how they could be orchestrated and blended better.

III. Analysis of Form, Techniques and Multiphonics

The piece that resulted from this collaborative project with the Quasar Saxophone Quartet, called En s’effaçant, is made of six different sections. As described in the previous part of this essay, each section explores a specific type of material (either textural, gestural or a combination of both), and deals with a specific idea relating to the poietic concept of petrichor.

Section 1 (textural materials): mm. 1–60

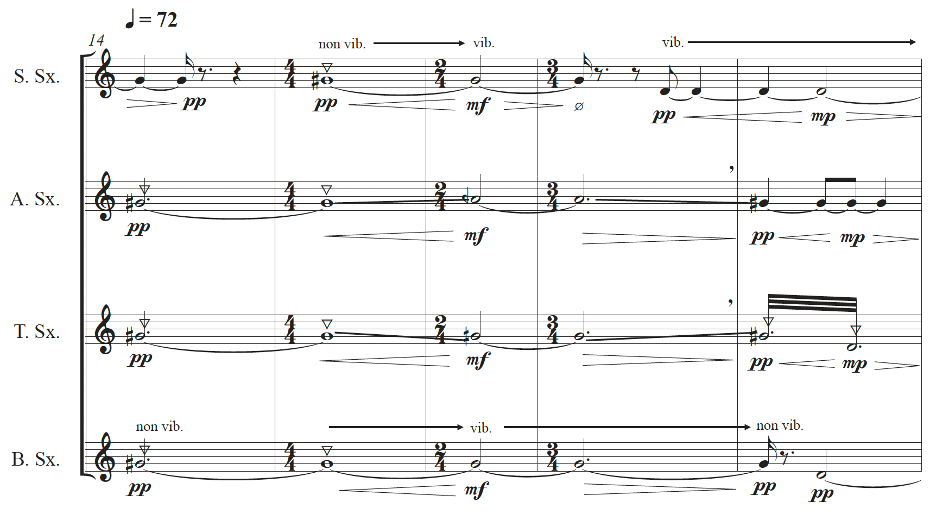

I have observed that most loud and grainy multiphonics tend to sound closer to us and occupy a smaller space compared to smooth and quiet multiphonics, due to their timbral, dynamic and textural characteristics. I explored this dichotomy in the first section of the piece, in which I opposed two distinct spaces: (1) a close and narrow space obtained through a textural polyphony of loud and grainy multiphonics combined with flutter-tonguing effects (space #1, Figure 1), and (2) a more distant and wider space (space #2, Figure 2) that progressively emerges from a sustained note that gradually becomes quieter (aiming to recreate the sonic effect of a sound progressively getting further away from us). This second space is obtained through a combination of soft microtonal beatings, microtonal glissandos, and vibrato effects:

Figure 1: Opening of the piece, using a grainy small and close space (space #1): mm. 1–4

Figure 2: Quiet and large distant space (space #2): mm. 14–18

Both spaces are then repeated and transformed multiple times in alternation in this section of the piece. Some transformations are based on rhythm (space #1: mm. 22–26, space #2: mm. 27–32), pitch (space #1: mm. 44–47, space #2: mm. 45–52), or timbre/texture (rapid cross-fade[2] repetitions between space #1 and space #2: mm. 33–43). The final occurrence of these two spaces (mm. 53–60) figures a “cutting” technique[3](borrowed from electroacoustic composition) in which the two spaces keep interrupting each other unexpectedly.

Section 2 (semi-textural, semi-gestural materials): mm. 61-96

To renew the listener’s attention, the second section of the piece focuses on materials that are less spectrally dense, with fewer grainy and loud multiphonics than in the first section, and it uses more gestural articulations (such as fast ascending movements). The space opens from a distance (in a similar way than space #2) and is contrasted with short, loud accented dynamic “incrustations”[4] (sudden sforzandos and fortepianos), creating a series of articulations that give the impression of sounds suddenly coming closer to the listeners before receding into the distance (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Spatial articulations and dynamic incrustations in Section 2 (mm. 61–62)

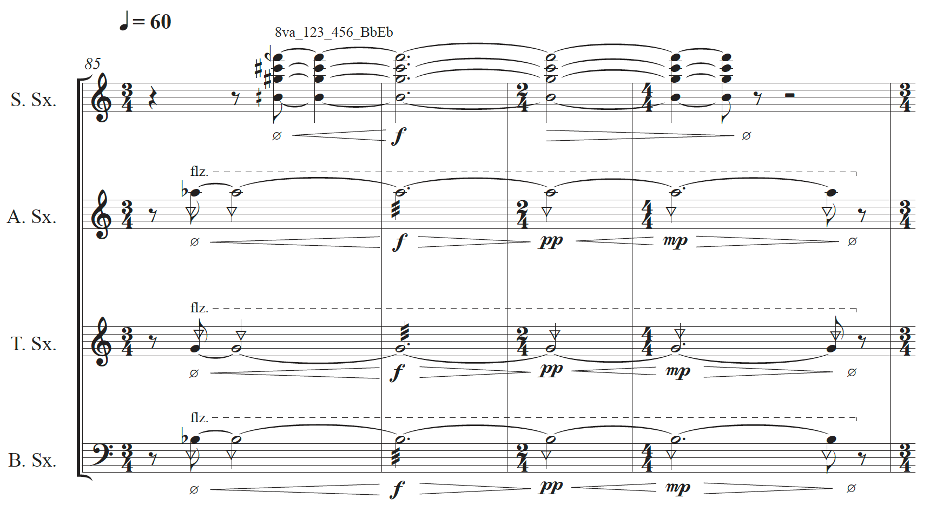

The soprano multiphonic used in measure 61 not only helps to connect Sections 1 and 2 together (as the same multiphonic was previously heard in Section 1 in mm. 57–58), but also serves to texturally and timbrally blend all the other saxophones together. The constant ascending legato appoggiatura figures of this section harkens back to the very first gesture of the piece (a descending legato appoggiatura) which was later repeated many other times in Section 1 (m. 6, mm. 28–32, m. 43, m. 58). The second section is thus very unstable, constantly accelerating, decelerating, and varying in volume at different moments. Despite this, it progressively follows a general “dissolution” process through rhythmic stretching and progressive dilatation of the material until it is played in its purest form (mm. 85–88, Figure 4).

Figure 4: Section 2 main material in its simplest form (mm. 85–88)

Section 3 (gestural material): mm. 97–120

This section features the most articulations and rhythmic complexity in the piece. The main material is a solo, gesturally unstable, half-aeolian (i.e., half pitch, half air noise) bisbigliando that is alternately transferred to other saxophone parts in a hocket style. The multiphonics used in this section serve different functions. The first is to enrich the space around the continuous, uninterrupted bisbigliando, creating a more interesting background. Using the multiphonic in a tremolo figure helps to rhythmically blend it with the bisbigliando (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Multiphonic tremolo in Section 3 (mm. 106–108)

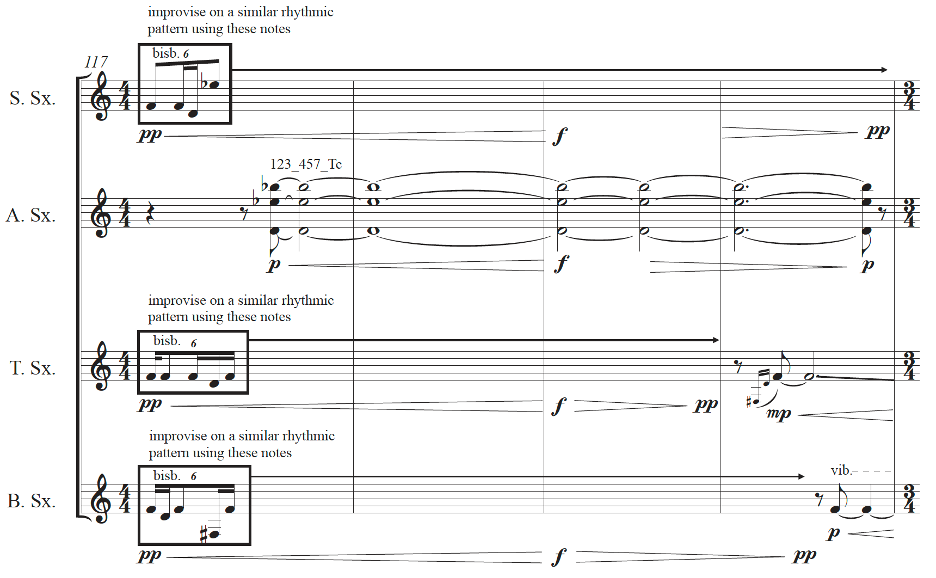

The second function of the multiphonics is to enhance the timbral blend between all the saxophones during textural moments, such as the one between measures 117 and 120. In this example (Figure 6), I chose a multiphonic that uses similar pitch material to the other saxophone parts to help with the blending effect.

Figure 6: Multiphonic timbral blend in Section 3 (mm. 117–120)

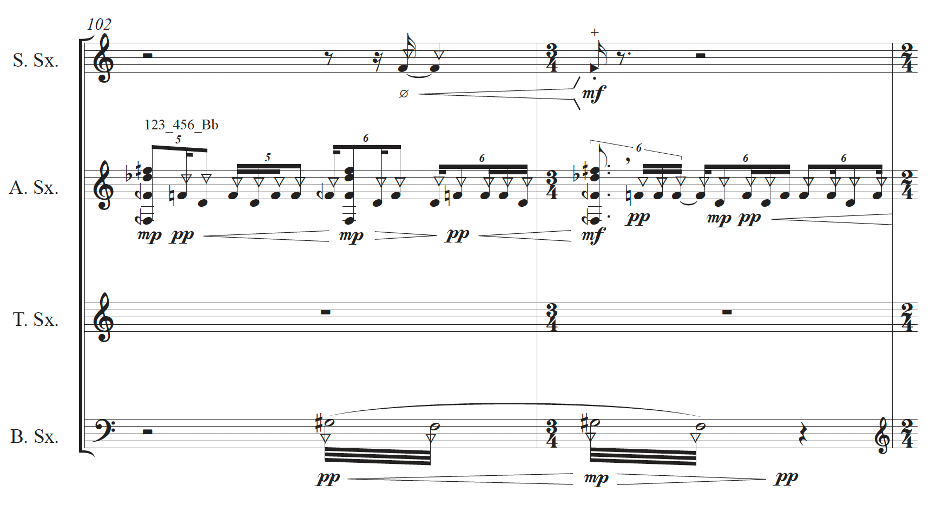

The third function is to add more textural, timbral and microtonal pitch variety to the bisbigliando figure. This function is realized on the alto saxophone and is only achievable on a multiphonic which can be produced quickly and with an easy fingering[5] (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Multiphonic textural and timbral augmentation in Section 3 (mm. 102–103)

Section 4 (gestural material): mm. 121–142

The first part of this section consists of a progressive microtonal ascending glissando (from F to G#) orchestrated for all four saxophones. This introductory textural material, which gradually becomes denser and louder, leads to gestural material orchestrated in two parts. The first part is a loud and grainy accent multiphonic by the soprano and alto saxophones with two loud multiphonics using the same fundamental note. These multiphonics are immediately followed by a gesture consisting of a series of fast, short, microtonal descending notes. These two juxtaposed materials are repeated with variations eight times. As the descending microtonal scales get slightly longer with each repetition, timbral and textural variations are introduced through orchestration, such as adding a glissando, a bisbigliando, or a smorzato figure along the descending scale (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Grainy multiphonic attack followed by microtonal descending scales in Section 4 (mm. 136–138)

Section 5 (semi-textural, semi-gestural materials): mm. 143–172

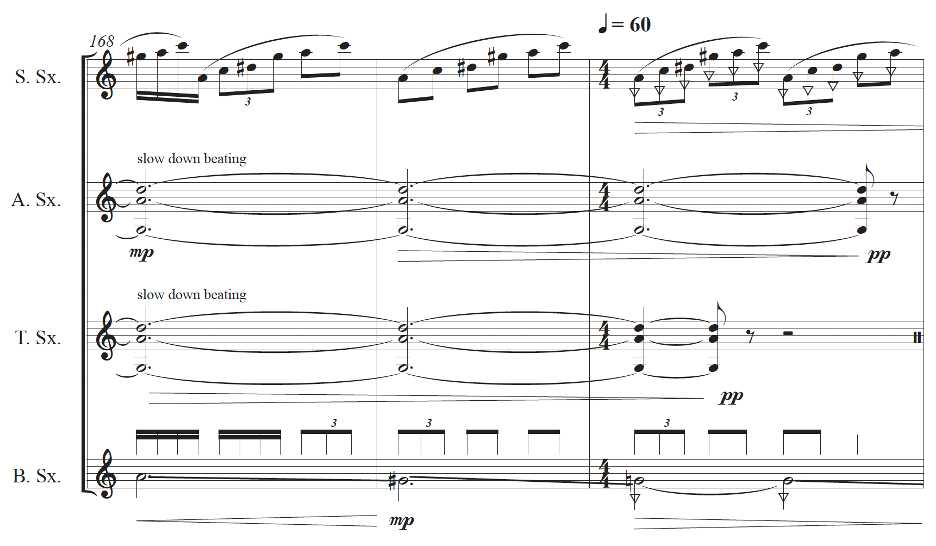

Section 5 reuses and develops the fast scale motifs from the previous section in an ascending and more polyphonic manner. Starting at measure 150, a repeated homophonic pulse interrupts this flow of notes and progressively develops into a more polyphonic textural material. This texture then transforms into a gestural material, splitting the four saxophones into two distinct layers: the soprano and alto saxophones repeat an ascending fast pattern that gradually gets higher, while the tenor and baritone saxophones play a slow-moving ascending glissando, interspersed with multiphonics that have a strong internal beating. At the end of Section 5, as the ascending scales in the soprano and alto parts get progressively slower, the beatings of the tenor and baritone multiphonics also slow down to emphasize the effect (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Multiphonics beatings progressively slowing down at the end of Section 5 (mm. 168–170).

Section 6 (textural materials): mm. 173–187

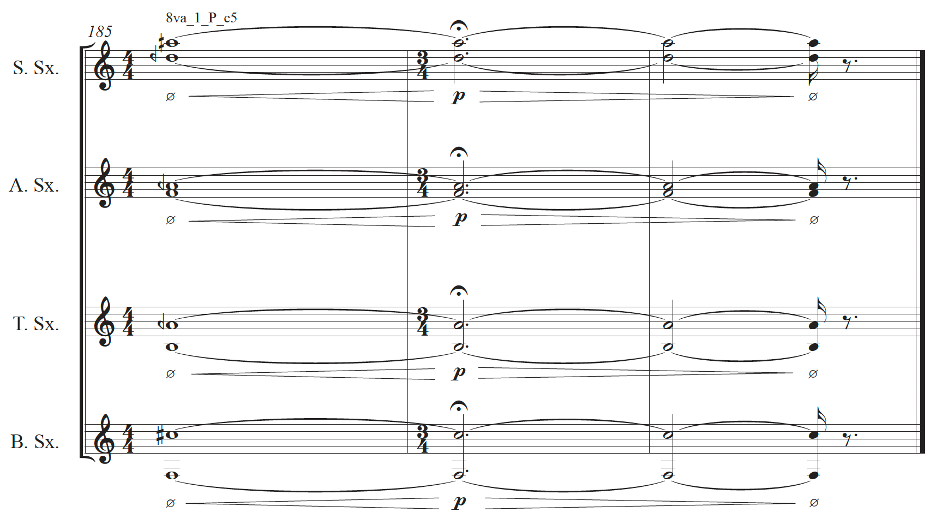

This section begins with the disintegration (slowing down and decrescendo) of the decelerating ascending scale from Section 5. From this, a polyphony of smooth and quiet multiphonics emerges, which then transforms into a multiphonic monophony. I chose the multiphonics based on their pitch materials and their timbre, to create a coherent blend and harmony resulting from the perception of all the combined multiphonics. In this section, I was primarily interested in creating a wide, distant space in which the smooth and quiet (“cloud-like”) multiphonics would be repeated and would slowly disappear until the end of the piece. I endeavoured to explore the subtle timbral and textural instability of these multiphonics in the final section to contrast with the beginning of the piece (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Closing bards of the piece (mm. 185-187)

IV. Conclusions

To conclude, this research-creation project helped me understand better how to orchestrate for saxophones and how to combine saxophone multiphonics timbres together. I learned how to efficiently create blends between different saxophones and how to use multiphonics to enhance specific types of blends.

By using multiphonics, I intended to create various timbral, textural and spatial perceptual effects throughout the piece. To summarize, here is the list of the different perceptual effects I endeavoured to produce in this piece through orchestration techniques on multiphonics:

To generate spatial contrasts: textural/rough/loud/small space vs blended/smooth/quiet/large space

To create cross-fade effects between two textures/spaces

To enhance spatial perception by opening a space with multiphonics juxtaposed with another material (stratification effect: foreground vs background)

To enhance timbral blend between similar materials

To enhance textural blend between dissimilar materials

To add some textural and timbral variations to a motif

To play with the beatings of multiphonics

To produce electronic-like sounds with smooth/cloud multiphonics using concurrent blend and the timbral and pitch instability of some multiphonics

I was able to retrieve some of the multiphonics I used from three different multiphonic databases (some multiphonics were overlapping between the three databases): the Q-Phonics library (the database created by the Quatuor Quasar), the Kientzy database (Kientzy 2003) and the Weiss database (Weiss 2010).

Overall, this composition experience allowed me to experiment further with my musical and extra-musical ideas, thanks to the three workshops organized by the Quatuor Quasar, which was essential to the realization of this composition. The workshops and the feedback received from Quasar were invaluable in my composition process and enabled me to achieve musical goals I would not have reached without their assistance.

Score and Recording

V. Bibliography

Kientzy, D. (2003). Les sons multiples aux saxophones. Édition Salabert.

Nattiez, Jean-Jacques. (1990). Music and Discourse: Towards a Semiology of Music. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Quasar Saxophone Quartet. Multiphonics table: Q-phonics. Q-phonics. https://q-phonics.com/en/multiphonics-table

Weiss, M., & Netti, G. (2010). Die Spieltechnik des Saxophons. Bärenreiter.

VI. Appendix: list of multiphonics used in En s'effaçant