Amortisseur Harmonique

Amortisseur Harmonique

Extrapolating a Language from Saxophone Multiphonics

Written for the Quasar Saxophone Quartet

Composers: Lila Quillin

Performers: Quasar Saxophone Quartet: Marie-Chantal Leclair, Soprano Saxophone; Mathieu Leclair, Alto Saxophone; André Leroux, Tenor Saxophone; Jean-Marc Bouchard, Baritone Saxophone.

I. Introduction

Amortisseur Harmonique (2024) is an eleven-minute work for saxophone quartet in which I explore the possibility of developing a cohesive compositional language from the qualities that make multiphonics unique—both sonically and structurally—in order to construct a multiphonic “story.” As composers working within a post-tonal system, it is our unique privilege–and thus responsibility–to define our own musical “home” and “away” so that the audience can appreciate the musical narrative. To define the compositional language of a piece means to articulate to the audience what the musical characters are and what their motivation is, so that when they are woven, interpolated, granted or denied closure, or manipulated in any way, the audience can feel the impact of that development.

In this project, the need to explore saxophone multiphonics established a prerequisite for the compositional language from the outset. This extended technique offers a diverse range of sonic textures that are easily recognizable and possess several inherently charismatic traits. The aim of developing a compositional language derived from multiphonics stemmed from a desire to bring these qualities to the foreground. I adopted a character-study approach in which the multiphonics serve as A material, “observed” by an artificial B material that imitates and develops their features. This framework allows for explicit commentary on the characteristics of the multiphonics while still granting them the freedom to connect and unfold expressively.

In the sections that follow, I will examine specific traits of multiphonics and how they were translated into elements of the non-multiphonic, observing material. I will also address how the internal structure of the multiphonics informed the larger form and development of the piece.

II. Extrapolation of Material from Multiphonics

Weight and Scale

Because of the technical precision required to execute them, multiphonics take a relatively long time to fully manifest and sustain. In the QUASAR Library, audio excerpts typically range from 4 to 15 seconds in duration. Their musical characteristics are best appreciated when given time to speak, as the relationship between their various partials and the resulting rich, ever undulating timbral landscape is where their artistic interest lies.

One of the most defining characteristics of a multiphonic is its simultaneous embodiment of two contrasting senses of scale. One is large: the slow, weighted progression of audible events—from the initiation of breath, through the buildup of partials, the sustain, the gradual decay, and finally the need to breathe again before the next multiphonic can begin. While some multiphonics, especially the louder ones, do exhibit a quick impulse, the overall tendency toward slowness and power establishes a broad temporal scale. It is difficult, for example, to “string together” multiphonics in the way one might connect notes in a traditional scale; they are, by nature, often self-contained microcosms.

At the same time, there is a contrasting small-scale present: the fine details within the fragility of breath, the beating interactions between partials, and the pitch undulations—sometimes shifting by as much as a half step, as in Q.T.20—all contribute to the intrinsic micro-level musical charisma of a multiphonic. To highlight this dramatic contrast in scale, most passages containing four to ten measures of small-scale rhythmic detail are anchored by a motivic pedal tone (especially evident in measures 1–45), and later, by a multiphonic.

Harmony

Multiphonics can be categorized harmonically according to intervallic content, pitch class, range, and harmonic density. A close study of the QUASAR Multiphonics Library reveals that most multiphonics fall into a few distinct intervallic categories. One such category consists of those built primarily from perfect fourths and fifths—such as Q.S.15—aligning closely with the harmonic series.

Figure 1. Soprano Multiphonic # 15

A more common intervallic pattern is that of pure intervals, such as the octave or fifth, with slight microtonal variation. Multiphonics containing these intervals are the most abundant in the QUASAR Library, making them of particular motivic interest.

Figure 2. Tenor Multiphonic # 20

Figure 3. Alto Multiphonic # 6

Figure 4. Baritone Multiphonic # 30

Figure 5. Alto Multiphonic # 3

Finally, most other multiphonics consist of intervals of seconds and thirds, forming harmonic clusters like those in Q.S.16. These clusters are the densest in harmonic identity, providing the most chromatically saturated space.

Figure 6. Soprano Multiphonic # 16

For the purpose of constructing a narrative, the most striking characteristic was the perfect interval with microtonal variation. It produces a harmonically compelling sound, offers substantial potential for developing musical material in relation to the microtonal “leading-tone” or “neighbour-tone” relationship in the non-multiphonic material, and generates the most prominent rhythmic beating that contributes to make the aforementioned contrast between large and small scale more perceptible. These multiphonics would later be developed into the A material of the piece. With these qualities in mind, I sought to create a seed for the B “Observing” material that could emulate the characteristics of these multiphonics in an artificial, non-multiphonic form. What I arrived at was a harmonic “peeling,” or a slight movement away from a static, polar pitch. By foregrounding this harmonic characteristic, this gesture aims to solidify one of the elements that allows multiphonics to sound both static and yet inherently mobile.

Figure 7. Motivic cell of B Material

As the challenge of arranging a variety of timbral textures arises, this motif offers a solution: the pitches of each multiphonic can be organized so that one of the component pitches of the multiphonic acts as a leading-tone to the next in performance. This approach unifies the larger-scale framework of multiphonics, even as smaller-scale content may occur between them. Using this principle, a progression of multiphonics was developed, establishing a broad framework that could later be filled with "observant" material. This passage serves as the opening of the piece, emphasizing the importance of the contrast in scale.

Figure 8. Chart containing the collection of multiphonics used in mm. 26-85.

These multiphonics were also chosen for their relative consistency in intervallic composure; the lowest note was always chosen as the most prominent note in the sequence, but the middle and upper voices, especially the upper, are also relatively consistent. This contributes to a sense of

homophonic motion that ultimately ended up being one of the primary stylistic approaches to this piece: treating multiphonics as shards of a chorale that can be reconnected whether by juxtaposition or with the help of the B Material.

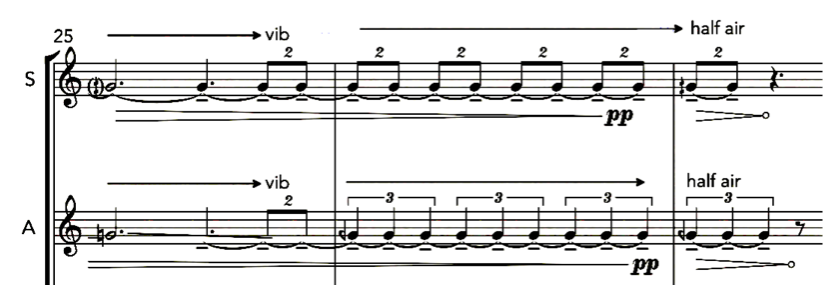

The pitch content of a multiphonic can be further exported to the “observant” material for development in multiple ways: they can be horizontally unstacked as a stretto, as seen in measures 25-27, or as a direct stacked explosion, as seen in measures 85-86.

Figure 9. Example of Stretto - measures 25-27

Figure 10. Direct Stacked Explosion - measures 85-86

They can also simply inform the pitch content of an entire passage: for example, the polar notes of measures 1-46 are developed out from from the Q.A.2 multiphonic that finally arrives in measure 26 (and are afterwards continued by the progression of leading-tone connected multiphonics in measures 26-85 documented earlier). The stretching out of pitches in this section is designed to amplify the larger sense of scale inspired by multiphonics even if we are rarely hearing multiphonics yet.)

Figure 11. Collection of polar pitches of measures 1-46

Figure 12. Alto Multiphonic # 2, arriving in measure 26

Rhythm

One of the most fascinating aspects of multiphonics, and one that forms a crucial part of their timbre, is the rhythmic beating of the various partials that make up the sound. Because of this, it’s the multiphonics in the intervallic category of pure intervals plus or minus a microtone that have some of the most fascinating and audible rhythmic results; another one of the reasons multiphonics of that class form the majority of those used in this piece. Here are some examples of these multiphonics, categorized by the speed of their beating.

Figure 13. Example of Rhythmic Development

These rhythmic characteristics shaped the construction of the “Observant” material in a number of ways. The first—and most direct—approach was to match the pacing of the Observant material to the beating rate of the accompanying multiphonics, as seen in measures 76–79. The subsequent feathered-beam deceleration, indicated in the blue boxes, represents the rhythmic articulation of the Observant motif.

Figure 14. Example of Rhythmic Development

A second, more timbrally focused approach involves replicating the smooth amplitude pulses characteristic of slower-beating multiphonics. This quality is distinctive to multiphonics: while conventional instruments can alternate between pitches rapidly, the rhythmic motion in multiphonics arises from the beating itself, producing a seamless sense of movement without discrete articulations. One effective way to approximate this is through vibrato. Though inherently slower than techniques like bisbigliando or trills, vibrato can be orchestrated in polyrhythms to achieve tha effect of multiphonics. As a result, controlled vibrato becomes a central feature of the piece, first introduced as a key element in the opening gesture (measures 1–7).

Figure 15. Example of notated vibrato

The rhythmic qualities of multiphonic beatings also contribute to the material generation of the piece by extending the sense of pulse beyond individual notes to encompass entire motivic cells. This broader application of rhythmic motion enables it to function on a larger structural level, reinforcing the work’s underlying preoccupation with the interplay between small- and large-scale form.

Because this kind of development relies heavily on repetition, it draws from techniques used in Baroque and Classical-era treatment of folk or motivic cells. In particular, the handling of the “Observant” material was modeled after Domenico Scarlatti’s Piano Sonata in C Major, where both full phrases and the smaller units within them are repeated, extended, and developed—often in tandem with the introduction of new material.

Figure 16. Example of development of motivic cells in Domenico Scarlatti’s Sonata in C Mayor.

Inspired by this approach, measures 1-42 make use of a certain “scale” of rhythmic cells that are advanced through as the passages progress. To replicate the relationship between interval and rhythm (beating) in multiphonics, each of these rhythms is introduced under the influence of one of the polar notes of measures 1-46.

Figure 17. Rhythmic Progression used in measures 1-42

The final rhythmic idea derived from multiphonics is the feathered-beam motif, which appears both at the smallest scale and at the broadest structural level of the piece—particularly in passages that accelerate or decelerate. This gesture serves as a temporal analogue to the neighbor-tone or leading-tone relationship that plays a central role in the harmonic language, as introduced by the B motivic cell: any stable pitch bent by a microtone alters the beating rate as the interval shifts. In this sense, the feathered-beam rhythm expresses in time what the microtonal inflection articulates harmonically. Certain multiphonics also display this kind of shifting rhythmic behavior. In Q.A.6, for instance, the change in beating speed—subject to the performer’s airflow—is so pronounced that I adopted it as a key motivic multiphonic. It marks every major structural transition and appears as both the first and last fully stated multiphonic in the piece.

Figure 18. Wave form of Alto Multiphnonic # 6.

With these scalar, harmonic, and rhythmic characteristics of multiphonics in mind, the primary B “observer” motif was established as three independent instruments sustaining the pitch of a multiphonic and gradually bending away, forming a feathered-beam figure that “activates” or extends its rhythmic character. This motif is fully realized for the first time in conjunction with a multiphonic in measure 66.

Figure 19. Full Statement of A + B Material

IV. Form: Arborescence and Accumulation

The piece unfolds in three principal sections. In the first, the scalar, harmonic, and rhythmic qualities of multiphonics are explored within the framework of the B material: small rhythmic cells that gradually expand in length, each underscored by a distinct pedal tone. This process accumulates and develops until it reaches a true multiphonic, offering retrospective context for the preceding material. The second section begins with the combined statement of A and B material in measure 56, then proceeds to repeat and systematically expand the six-measure gesture, with increasing emphasis on the rhythmic friction and beating. Initially, multiphonics appear individually, linked across time by leading-tone motion in one of their constituent pitches. In the third section, multiphonics begin to stack vertically as well as connect horizontally, forming a texture closer to a chorale. A coda follows, interweaving the densest vertical arrangement of multiphonics with a melodic development of the opening’s pedal tone. In summary: the first section isolates individual qualities of multiphonics (B material), the second presents multiphonics as elaborated units (A with commentary from B), and the third synthesizes both into extended passages (A+B integrated).

The consistent developmental strategies used across all structural passages derive from inherent qualities of multiphonics: accumulation and arborescence. Both techniques involve expanding and extending an initial cell while keeping that cell active, relying on pitch connections—whether through the replication and sustainment of a pitch contained in a multiphonic by an “Observing” instrument, or through the neighbor-tone or leading-tone motion of a particular pitch “peeling” away from a stable tone. Accumulation is first introduced rhythmically in the opening section, where small rhythmic cells cluster into progressively longer phrases, and later applies to the chaining together of an increasing number of multiphonics in the second and third sections. In this way, accumulation foregrounds the importance of linking musical cells into extended lines and emphasizes the potential of continuity in multiphonics as a motivic force.

Arborescence is a term coined by Xenakis that was used in pieces like Evryali (1973) and Mists (1980). It refers to the tree-like branching of material into variations, “connected to the idea of continuity, linear motion and growth” (Harley), as seen below in a sketch of the material in Evryali.

Figure 20. Graphical transcription from the score for Evryali (1973)” (Harley)

The B material in this piece represents a single branch of the broader process of arborescence, so it made sense to explore a development in which these branches could be extended and multiplied. Sustaining a multiphonic while superimposing a branching gesture derived from its qualities offers a direct way to highlight what makes each multiphonic unique. The use of arborescence becomes most concentrated in the third section and culminates in the coda, where it is applied both to a development of the original B motif and to a passage in which the multiphonics reach their greatest density.

Figure 21. B-Material arborescence in measures 165-167

Figure 22. Multiphonic arborescence in measures 168-170

V. Notes on the Title and Final Thoughts

While the development of the material and structure of the piece arose entirely from the isolated qualities of multiphonics, I was also inspired by the architectural concept of the “Amortisseur Harmonique,” or “Tuned Mass Damper.” This device consists of a large, high-density sphere suspended by springs at the top of skyscrapers, designed to counteract the effects of earthquakes, storms, or other disturbances by absorbing or canceling out unwanted frequencies. ass absorbing external forces to restore balance to a structure resonated deeply with me, particularly in relation to the B material I had been designing — the friction between a stable, balanced state and the oscillation caused by an outside force. This metaphor also became a powerful lens through which to view the piece as a whole: the tension between the static, stable multiphonic and the non-multiphonic forces that push it beyond its natural resting point. This concept helped clarify and refine the story I wanted to tell and is a direction I hope to continue exploring in the future.

I believe the creation of a musical language derived from the acoustic features of multiphonics was ultimately successful. In the end, I felt confident that the elements of the piece clearly belonged to the same sonic world and demonstrated a noticeable appreciation for the multiphonic 'sound.' However, my conclusion from this experience was that I had only completed the first step in fully executing this concept. While the sound world and material possessed potential energy and an effective series of internal relationships, there was a lack of horizontal, lyrical, or narrative development. It was easy for me to juxtapose elements to clarify their relationships, but there wasn’t enough motivic drive, momentum, or clarity to create long-term narrative tension. Given the richness of multiphonics and the specificity of this language, this project offers a medium that I am eager to continue exploring in future compositions.

All Multiphonics Used:

Soprano: Q.S.7, Q.S.15, Q.S.23, Q.S.25, Q.S.32, Q.S.43

Alto: Q.A.2, Q.A.3, Q.A.4, Q.A.6, Q.A.13, Q.A.17, Q.A.21, Q.A.25, Q.A.26 Tenor: Q.T.16, Q.T.17, Q.T.20, Q.T.21, Q.T.30, Q.T.34

Baritone: Q.B.4, Q.B.25, Q.B.30, Q.B.33, Q.B.50