A short Analysis of Ravel’s Alborada del Gracioso with the concepts of Functional Orchestration

A Timbral and Orchestrational Pluralistic Analysis

A short Analysis of Ravel’s Alborada del Gracioso with the concepts of Functional Orchestration

Fabien Lévy [1]

Timbre and Orchestration Resource | Modules | Taxonomies of Orchestration

Published: July 2nd, 2022 | Copyright 2022 TOR

1. What is ‘functional orchestration’ ?

1. a) Functional orchestration has basically four objectives:

i. Isolation and verbalization of universal principles on the composition of timbres. Such principles would be mostly based on acoustics, on psychoacoustics or on phenomenological observation of gestalt principles of sound-organization.

ii. Development of general functions to categorize different operations on timbre (space, dynamic, timbre-quality), on imbricated entities (f.i. textures, chords, doubling, coupling), and on articulation between independent entities (successive or simultaneous merging / discrimination of entities, fades, contrasts, dynamic articulation, etc.);

iii. Extension of the understanding of the instrumentation, which has hitherto been often limited to registers, timbre and dynamics, to include further "dimensions" in order to better understand the function of the instruments within the ensemble. Consideration of the instruments and group of instruments under the aspect of their possible functions within an ensemble, and better understanding of the notion of composite and virtual instruments.

iv. Identification, categorization and improvement of these instrumental functions and their mechanisms in relationship with their perceptual effects, and understanding how their related instrumentation techniques have changed throughout different periods, styles and authors.

1. b) Distinction between functions, techniques and effects

An orchestration function is a musical category of instrumentation principles aimed at obtaining a perceptual effect through one or more technical operations of instrumentation (that are often called techniques of instrumentation) performed by the composer. Indeed, the functional operation is a musical aim or goal, verbalized or not verbalized by the composer, but clearly in their mind before starting to write, which helps them to choose a particular technique to achieve a particular perceptual effect. Examples of orchestrational goals might include: “I want to obtain a merging entity from different elements”, “I want to obtain different layers, perceptually discriminated and with different weightings”, “I want to obtain a contrast here” or “a particular form with a climax there”, “I want to obtain a crescendo”, “I want an acoustically 'dry' or 'wet' sound”, etc.

Orchestration functions are therefore ideally pan-historical and universal, ideally available for any type of music, instrumental or electroacoustic, with or without pitch, written or non-written, composed or improvised.

Example 1:

Crescendo as a function (creating an overall crescendo as a goal) is not a crescendo as a technique (writing a crescendo sign below one instrumental stave). A function crescendo can indeed be obtained with different techniques: addition of more instruments, change of register of the instruments (e.g., horns going higher in the classical music, see fig. 1.1), crescendo on a group of instruments, etc.

|

Effect |

Function |

Techniques |

|

I want to perceptually obtain a progressive change of dynamics |

Musically, it means that I want to obtain a crescendo |

To obtain it, I can use following techniques:

|

Ex.1: crescendo as a function, technique and effect

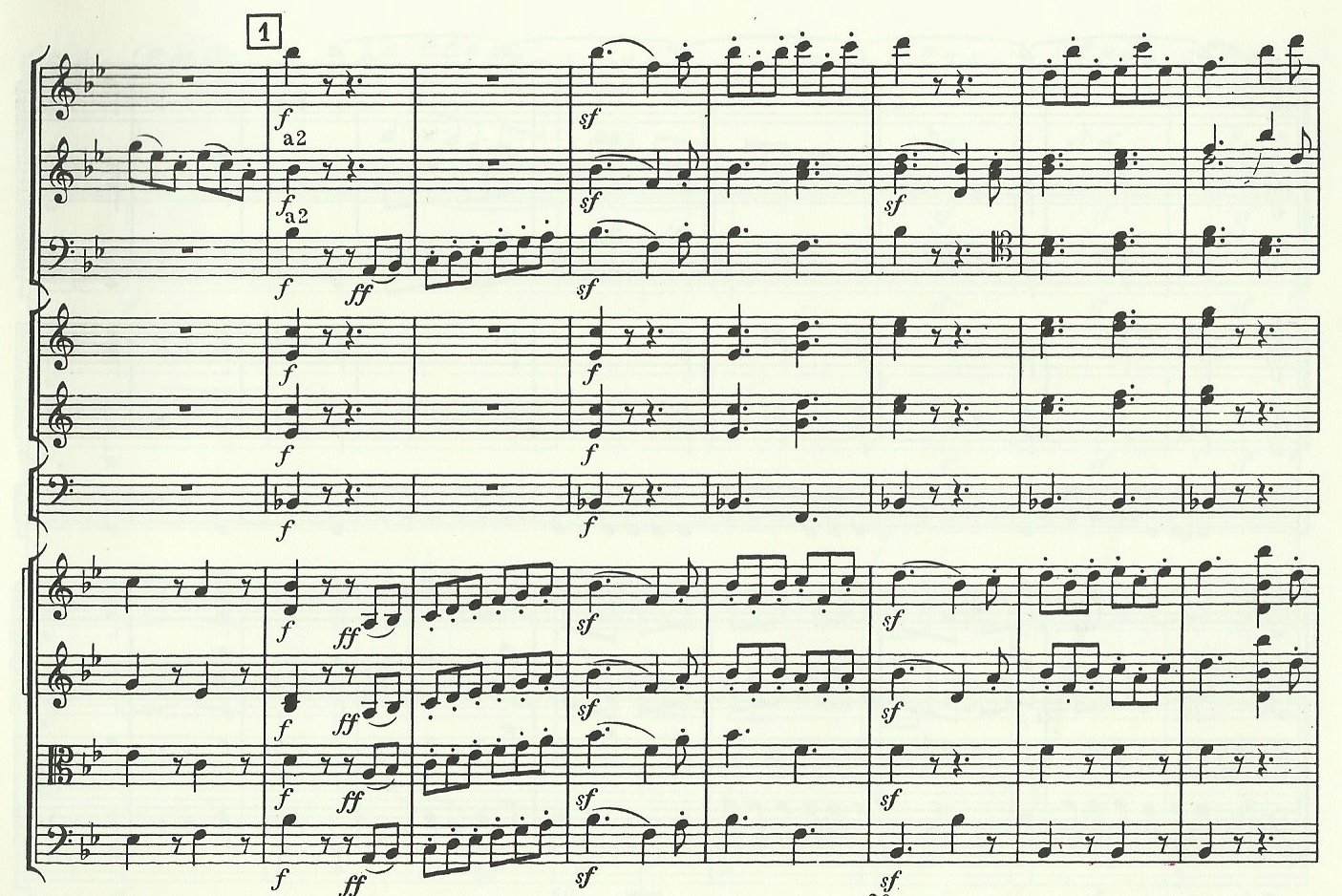

Fig 1.1: Joseph Haydn, Symphony Nr. 98, 4th Mvt., mm. 15-23, © Dover edition.

The functional operation crescendo is here mostly obtained by higher pitches (overtones) on the natural horns and trumpets.

(click for score and audio)

Example 2:

We call horizontal coupling an orchestration function where two or more instruments are written (technique), so that they are perceived as one merged entity along the timeline (effect)[2].

The most known technique for an horizontal coupling is the doubling technique between instruments, where two instruments play synchronically, often sharing the same pitches or same pitch-classes or same interval-parallel pitches in order to cause the perceptive fusion. If we go into more detail, the doubling techniques can be classified according to more precise functions aiming different perceptual effects. We classify these functionalities into six categories (beware, each example can have multiple effects. We give here the main effect):

- i) Dynamic reinforcement

- The doubling causes an increase in amplitude

- Example: horn 1 + horn 2 (there will also be a slight chorus effect)

- ii) Spatial projection reinforcement

- It will reinforce or change the characteristics of the spatial projection

- Example: horn (undirectional) + tbn. (directional)

- iii) Spectral densification

- The timbre of the resulting virtual instrument will be little changed, except for a densification of its spectrum

- Example: celli + cb.

- iv) Change of timbre

- The sound of the resulting instrument will be changed in color, but the instruments composing this new timbre will be recognized

- Example: xyl. + fl.

- v) Doubling for tone-reinforcement

- The color of one of the instruments remains predominant, but its tone will be clarified (reinforced)

- Example: celli+bsn

- vi) Mixture (term used by Marc-André Dalbavie inspired by organ techniques).

- The coupling of the two instruments will create a new color without the origin of the instruments being recognizable. A new timbre emerges.

- Examples: One of the first and especially paradigmatic example of mixture is that between clarinet and oboe in the first motif in the first movement of Schubert's Unfinished Symphony (it almost sounds like a saxophone). Examples of other well-known mixtures are the imitation of the organ (spectrum, air) in the Dies Irae of the Symphonie Fantastique by Berlioz with a mixture of four bassoons in their low register and two ophicleides, the last playing one octave higher (instead of the traditional usual unison in the doubling for tone-reinforcement). This mixture gradually awakens to monstrous life with rhythmic strings and timpani coupling (See fig. 1.2 below). Further known examples of mixtures are the imitation of a foghorn by the octave-doubling of a trumpet and English horn in Debussy's La Mer, the numerous mixtures (not only in unison or octaves, but also as (octaved) fifth and decimal in the sense of 22/3’ - and 1⅗′- Aliquot register of the organ) in Ravel's Bolero (number 8, for instance) or in the Piano Concerto by Ligeti (two parallel piano lines at intervals of six octaves and fourth in the second movement, bar 32, Clar. in low register and harmonica in countermovement at the end of the same sentence, bar 79).

|

Technique |

Function |

Effect |

|

I observe or write a doubling |

This doubling can have different musical functions:

|

This doubling can aim indeed different perceptual effects:

|

Ex.2: doubling as a function, technique and effect

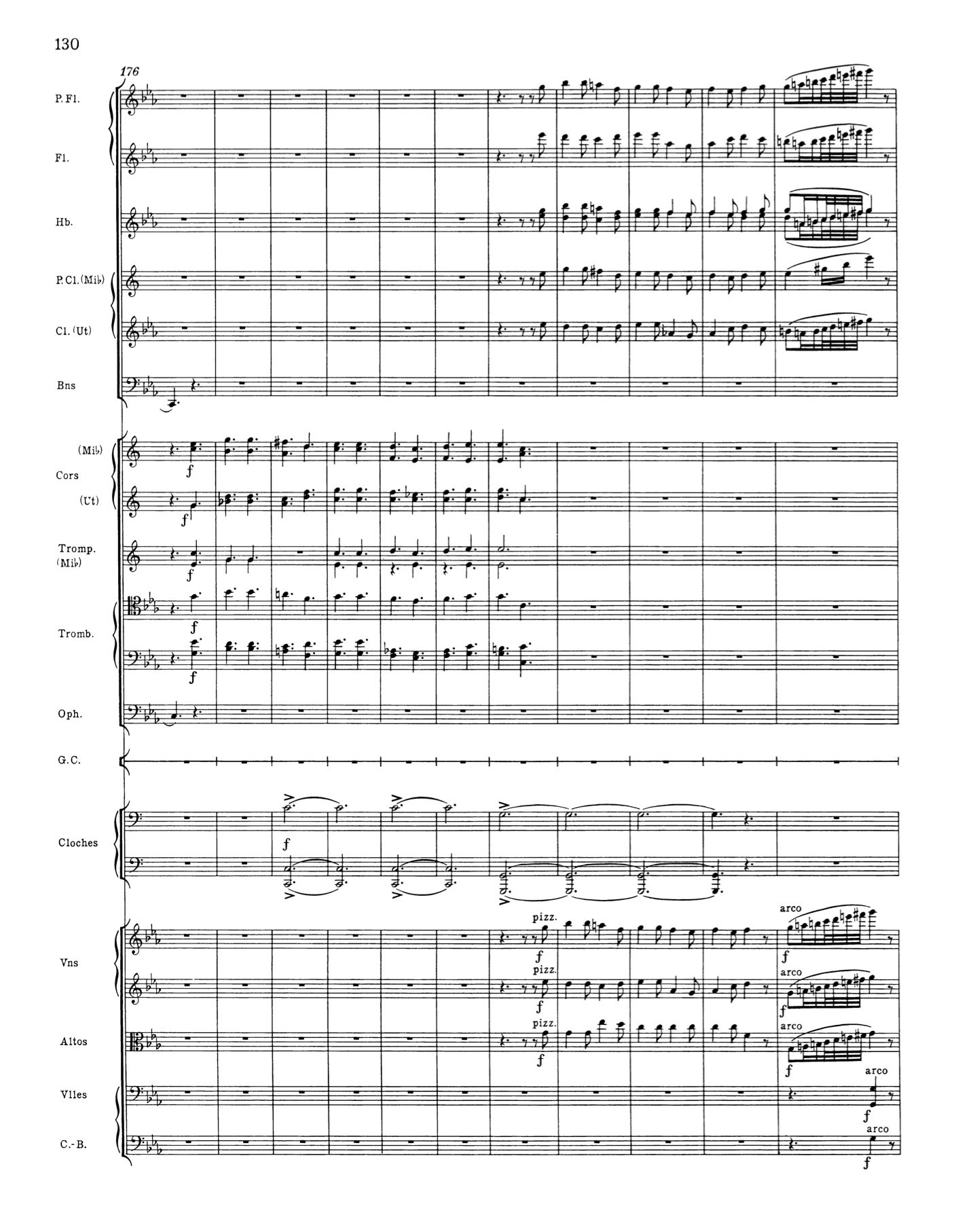

Fig. 1.2: Hector Berlioz: Symphonie fantastique, V Mvt., Dies Irae, Number 16

Example of coupling without doubling: winds, celli and timpani are coupled, but only the four bassoon and ophicleide are in homorhythm, the whole construction creating a complex virtual instrument

(click for enlarged score)

1. c) Instrumentation doesn’t only apply to timbre

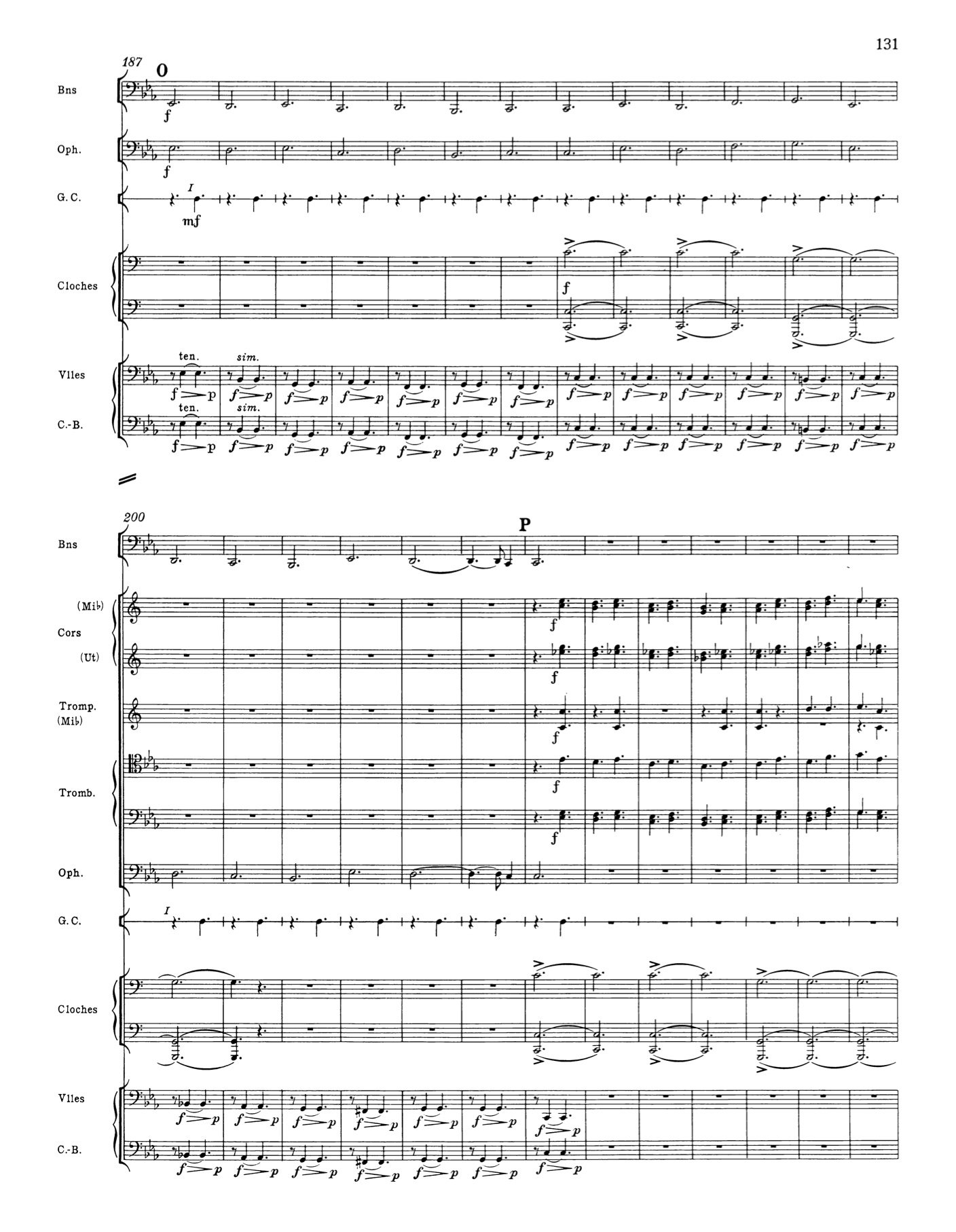

Instrumentation has three main families of aim-functions (see fig.1.3):

i. Functions that apply on musical elements that aim to be perceived as one entity.

ii. Functions that apply on musical elements that aim to create a perceptual separation [=segregation] of entities, either 2a.: vertically (separation of layers, hierarchization of layers such as foreground and background, etc.), or 2b.: horizontally (contrasts, transitions, ‘tree-logic’, etc.)

iii. Functions that apply on musical elements that aim to create Sound-Engineering-like effects. We will call these Sound Mastering functions.

Fig.1.3: Three main archetypes of functional operations

(click for full size)

i. Functions that apply on elements perceived as one entity

The different technical operations in orchestration on elements perceived as one entity can impact the perception of

- dynamics (crescendi, decrescendi, climax)

- space-quality (localization, directionality, focus)

- timbral quality

of the perceived entity.

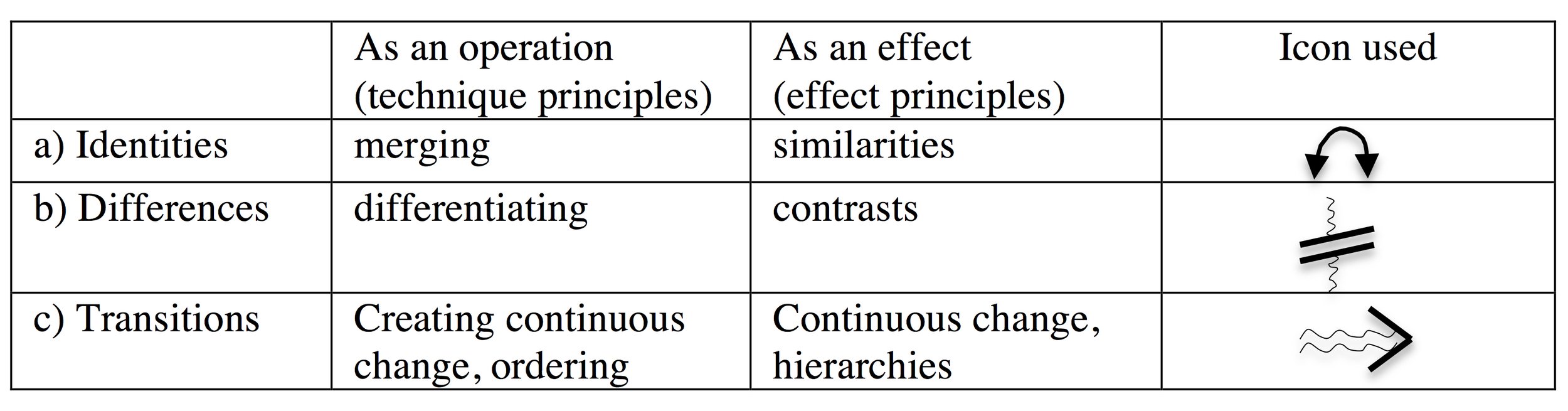

ii. Functions that apply on elements perceived as separated entities (counterpoint, layers, voice-leading, contrasts) are of three types of aims :

- dealing with or reinforcing Identity

- dealing with or reinforcing Difference and hierarchization

- dealing with or reinforcing Transition

Fig.1.4: archetypes of operation on elements perceived as separated entities

- This distinction can be applied to functions of articulation between successive entities (time-fields): analogies of timbres, contrasts, gradual transition.

- This distinction can be applied to functions related to the articulations of simultaneous/concurrent entities: merging functions, segregation functions (and hierarchization of layers –melody accompaniment, etc.-)

iii. “Sound-mastering“ functions

It concerns functions for operations on the overall musical result: focus, resonance, presence, sound of the whole body, musical emoticon[3] (punctuations, interjections, etc.).

1. d) Consequences in instrumenting or analyzing a music piece in using concepts of functional orchestration

Here are some tips for instrumenting or analyzing a piece:

i. An orchestration analysis (like any other type of analysis) is not simply a description of what happens on the score (“here is a clarinet“, “here are the strings“). To gain insight into the work, one must first ask: what did the composer want to reach here? (they originally had an empty page, what was their aim?)

ii. An instrumentation or an analysis can’t be only functional. Once the functions are understood, the next step is to see which techniques were used or could be applied.

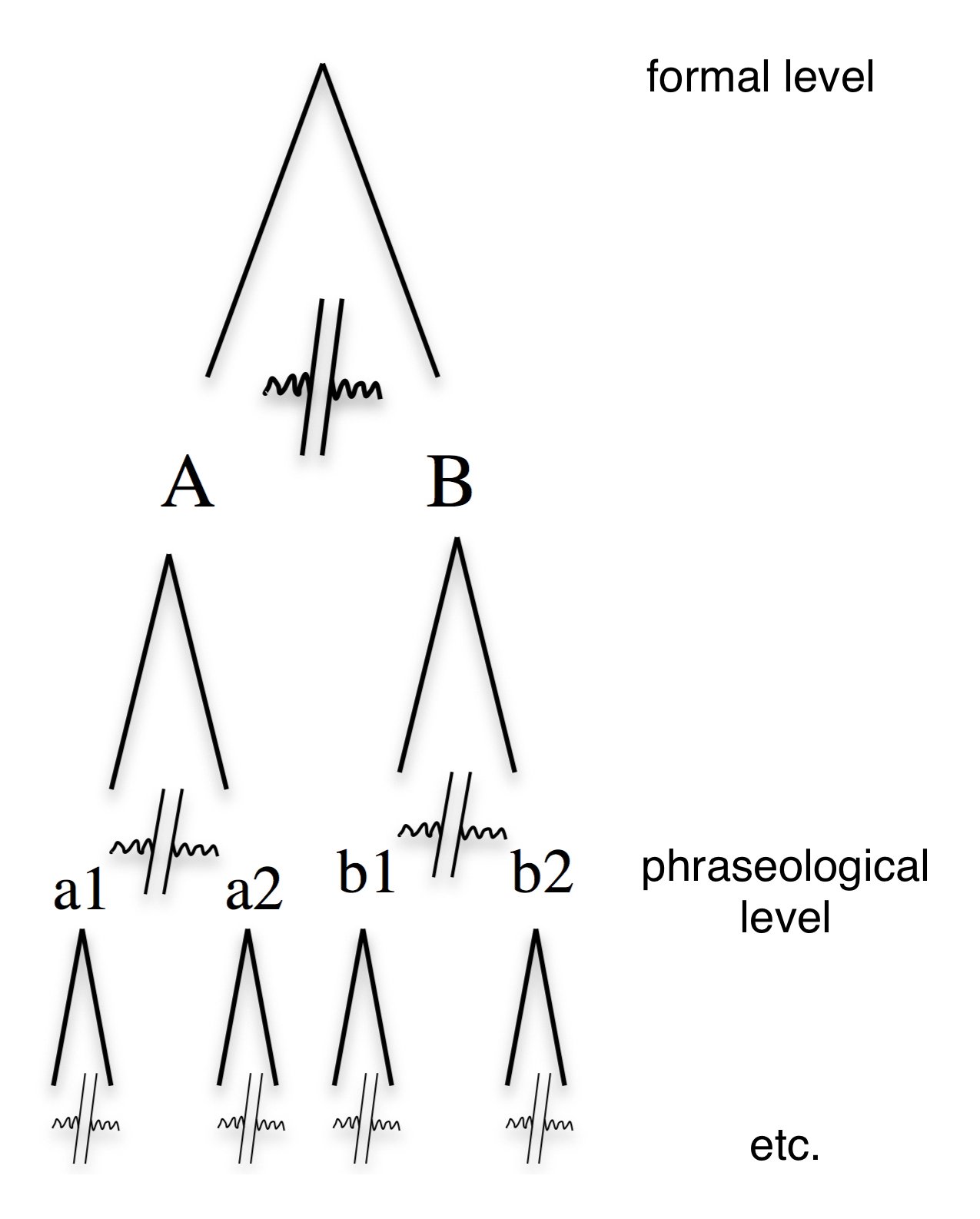

iii. While instrumenting or analyzing, it is advised to always analyze the form first. This is indeed the time-line strategy of most composers. And it is then advised to go deeper in the form, even on a further level than in a classical thematic/segmental form-analysis, in to the phraseological level:

- on the first formal levels, instrumentation follows or must follow the construction and the articulation of the different sentences: thematic differentiations, developments, contrast between periods, transitions and crescendi, analogies between entities (sometimes in different tonalities or different dynamics), strategies of hierarchization of climax.

- On the deeper levels, the instrumentation follows or must follow the composition of sentences (presentation/continuation; Vordersatz/Nachsatz).

- On the phraseological levels, the instrumentation musically accompanies the construction within the sentence: ‘questions/answers’ (called basic idea vs. cadential idea by William Caplin, even if these terms apply more into a certain type of tonal western music), fragmentation, accents, and even some musical emoticon that make the sentence understandable.

Note that in most cases (with some notable exceptions, like the rhizomatic-type instrumentation by Beethoven), the tree-logic principle is respected, even unconsciously: orchestration contrasts at higher levels are stronger than orchestration contrasts at lower levels, so that the meaning of the construction is always perceived.

Fig.1.5: tree-logic principle

1. e) Summary table of different functions (updated Mai 2020)

1. Functional operations on elements perceived as one entity |

|

a. Operations on Dynamics Strategies for crescendi, decrescendi, differentiated climax, reinforcement, etc. |

|

b. Operations on Space

|

|

c. Operations on Timbral Composition

|

2. Functional operations on elements perceived as separated entities |

|

Four different aims:

|

|

a. Functions of articulation between successive entities (time-fields)

|

|

b. Functions related to the articulations between simultaneous/concurrent entities

|

3. Sound-mastering functions |

|

a. Focus functions

|

|

b. Presence functions

|

|

c. Overall Background |

|

d. Musical emoticon: punctuations, interjections |

|

e. Ensemble-treatment mastering techniques

|

2. Analysis of Ravel’s Alborada del Gracioso using concepts of ‘functional orchestration’

2. a) Form & Tree logic in Alborada del Gracioso

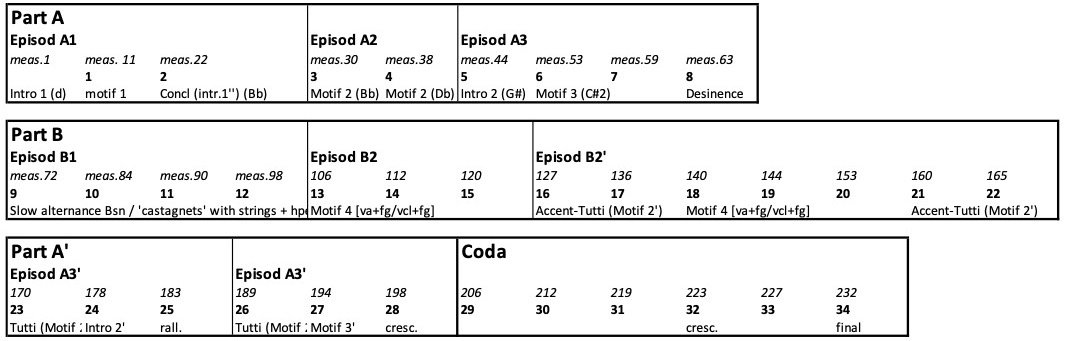

As explained in 1.c, Instrumentation isn’t only about timbre but also consists in accentuating articulations between different simultaneous or successive entities, whether these articulations are differentiations, relays, contrasts, analogies or transitions between entities. The instrumentation is in particular at the service of the form, and often follows the ‘tree-logic' principle (Fig. 1.3). Indeed, one cannot understand an instrumentation without understanding the formal articulation of the piece in all levels, from the highest formal level of parts until its deepest phraseological level.

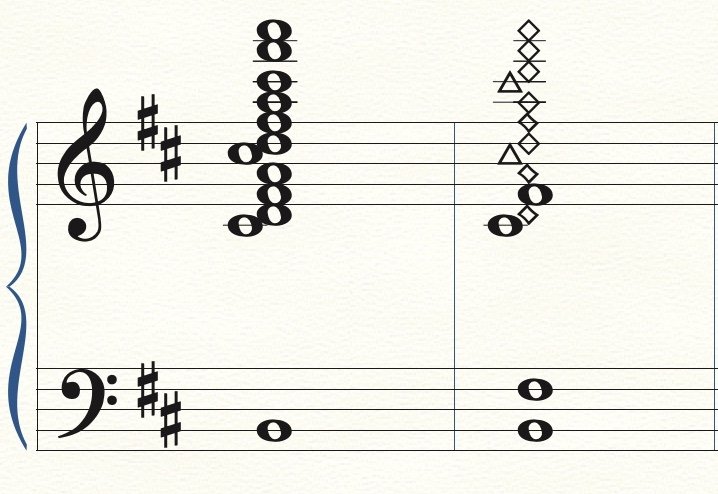

Alborada del Gracioso is composed in a simple ternary form: [A vif / B lent (rehears. mark 9) / A’ vif (mark 23)]. Each part is divided into episodes, often imitating the sound of a dance, or a character, or instruments related to Spanish folkloric music (guitar, castanets, rasgueado, etc.)

Fig.2.1: Form of Alborada del Gracioso

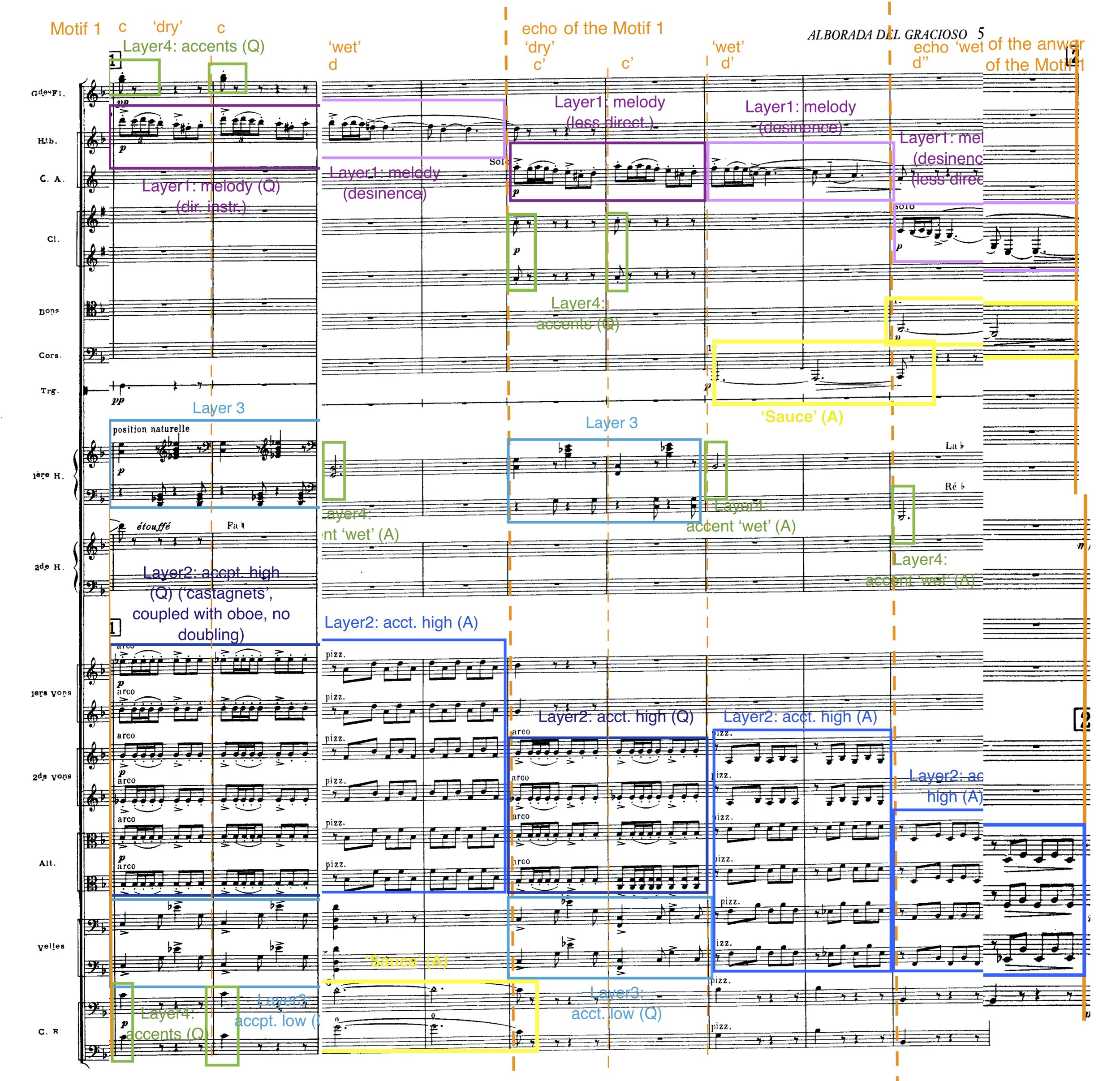

2.b) Functional analysis of the orchestration of the first episode (mm.1-29): imitation of a guitar rhythm played by different fingers

Let’s go deeper into the ‘tree logic’ of the first episode A1 (mm.1-29). It can be separated into three sub-episodes -an introduction (meas.1), a first motif (meas. 11) that is orchestrated in a contrasting manner, and a conclusion/transition (meas.22, rehears. mark 2) using the same material as in the introduction. Therefore, let’s analyze the two first sub-episodes. Within each of these two sub-episodes, we can even observe fine orchestrated contrasts which follow the different phraseological moments of these sentences ('question’/’answer', accents):

Fig.2.2: tree-logic analysis of the first episode

The very beginning of the introduction is an imitation of a flamenco guitar, already sketched in the piano version. Note how Ravel contrasts the rounder sound that would be played by the thumb on a guitar versus what would be played by the four other fingers of the hand. The thumb is here orchestrated with [pizz. violin 1 + viola in unisono], all in open strings and doubled with a harp pd.l.t in the middle register. On contrary, the arpeggiated chord played by the four other fingers of the hand are drier chords (with three different instrumentations) of pizz. in mostly fingerboard positions, without harp, and with additional several 'blurring' of the sound (enharmonics [D open strings + D on the G string]; half tone or major seventh intervals; sometimes three notes in the chord which obliges an arpeggiated chord, like in the guitar; etc.), to even more contrast the two colors.

Fig.2.3: Imitation of the thumb and of the other fingers (rasgueado) at the beginning

A similar contrasted effect is repeated at the very-end of this introduction, before the second sub-episode, but less clear for the thumb-effect. It opposes a “meta-thumb“ on the beat with open strings of double bass and ‘false open strings’ (fifth [D-A] one octave lower) on the celli, then only celli in the decresc. vs. low viola and violin fifths on the syncopes, both layers equally diminishing in a decrescendo (principle of equal balance between layers in step-wise cresc. oder decresc.)

Fig.2.4: Imitation of the thumb and the other fingers of a guitar, step-wise decresc. (mm. 10-11)

Note that in the coda (rehears. mark 29, meas. 206), Ravel uses an even 'drier' imitation of this thumb-effect, the bassoon replacing the harp, and the pizz being no longer open strings for the thumb-like sound.

The second part of this first episode introduces a first real motive. It is more contrasted than the fine nuances of the opening section: a solo oboe, which is a directional instrument, plays the melody (in purple in the figure 2.5) accompanied by several layers of accompaniment in a “tutti-like“ writing: for the "question" part of this motive, an accompaniment with arco strings in homorhythm with the oboe imitates within this close-position chord a castanets-like rhythm (see for example the marcia funebre of the Eroica, where the strings written in close-position imitate the snare drum-like rhythm of a funeral march). There are two further layers: a trochaic rhythmic accompaniment in the low register in pizz. +harp (in light blue), and some accents (in green). The "answer" part of this motive is, like often in the more classical literature, more “wet“, using orchestration techniques that produce a a pedal resonance (a “sauce“, in yellow), beautifully realized with a double bass harmonics in its first apparition. The motif is then repeated in echo, always less acoustically-directional and in decrescendo, with imitations of each functional layer in equal balance: the melody (purple) is played by the English horn rather than the oboe (as the E.h. has a rounder less direct radiation pattern); the two accompaniment layers (navy blue & light blue) in the ‘question’ are less dense, as well as the green accents. And the pedal (yellow) is played by the horn in its low register and p instead of the double basses. Finally, the echo of the echo (third step of this step-wise decresc.) of the response is even less directional: clarinet in the chalumeau for the melody (instead of Engl.. horns), pedal in the bassoon (instead of horns), which dark colour in this register fits with the clarinet and stays pitch-precise.

Fig.2.5: analysis of the instrumentation of the motif 1 (mm.12-21, step-wise decresc.)

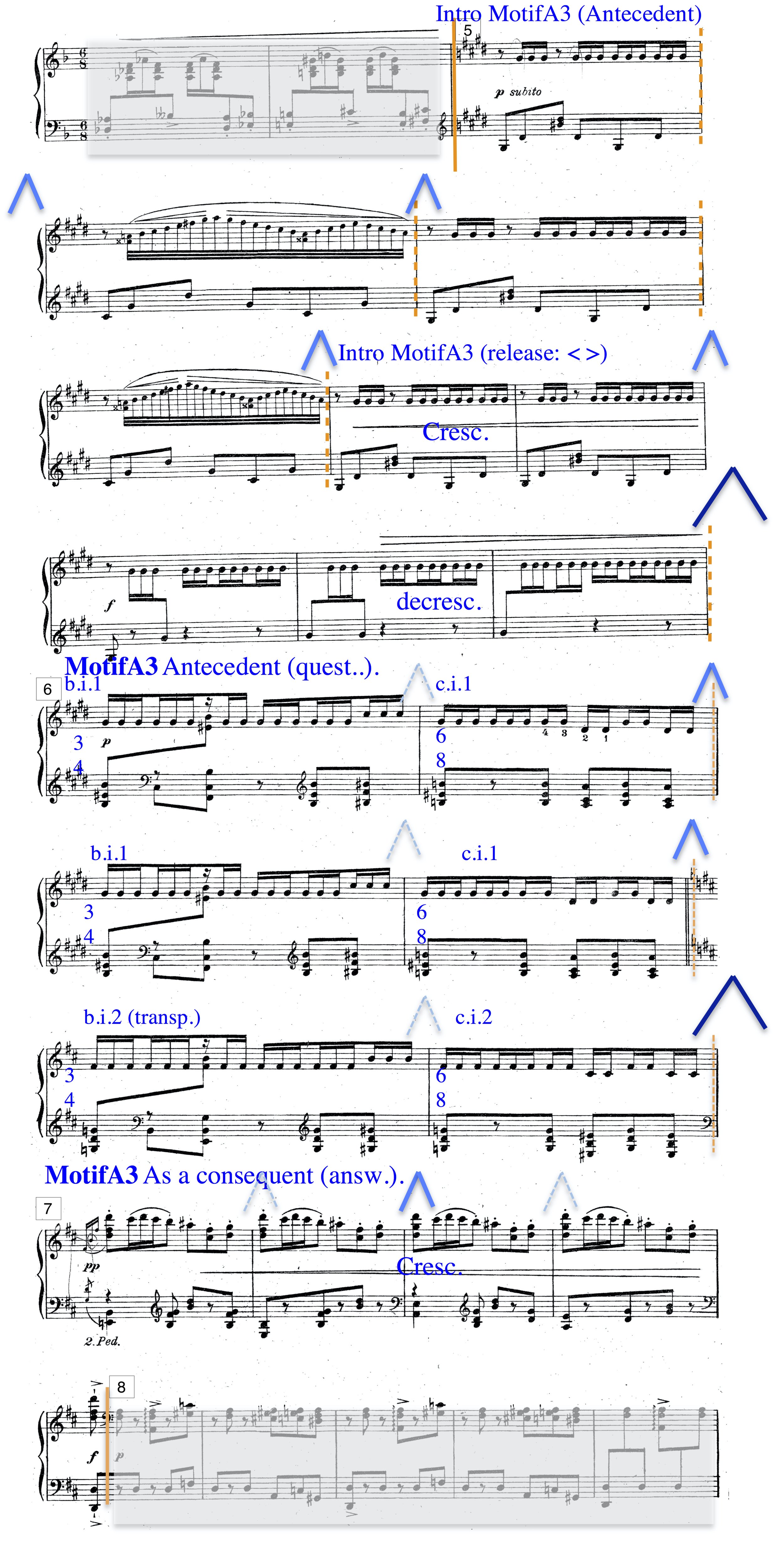

2. c. Functional analysis of the orchestration of the Episode A3 (mm. 44-58): imitation and magnification of the sound of a flamenco tremolo

The guitar being a non sustained instrument, this instrument is also known for the Francisco Tárrega's classical and flamenco techniques of tremoli (three fingers a-m-i or four fingers i-a-m-i) in order to sustain the sound. In the third episode of the first part, Ravel tries, on the piano, like in the later orchestral version, to imitate and magnify this technique.

The form of this third episode is bipartite, the two parts being clearly contrasted in character: The antecedent of the episode (reah. mark 5) is made from material imitating a repeated note G#, first in a long introduction, then introducing a new motif, actually derived from the beginning of the piece (mm. 1 & 2). The introduction itself can be divided into two alternations of repeated notes and a long ascending and descending melisma, followed by a long crescendo-decrescendo of G#. Each antecedent, consequent and transition can be deeper analyzed into phraseological moments (see piano score below).

Fig.2.6: Form of the third episode (Piano score, mm.44-62)

The instrumentation of the alternation [repeated G# / ascending-descending melisma, rehears. mark 5] of the introduction alternates a muted solo trumpet with, for the ascending-descending melisma, two layers with two different functions: the ascending/descending melisma itself (Hpe+flute in doubling, first in unison, then in octaves), and a ‘pedal’/‘sauce’ layer with two stopped horns “around“ the G# (beating interval [g-a]) –in order to have a reminiscence of the sound of the muted trumpet. Pizz. string accompany these figures, and a very light stroke of cymbal with stick triggers the melismatic figure.

Fig.2.7: Instrumentation principle for the mm.44-47 (Introduction, antecedent)

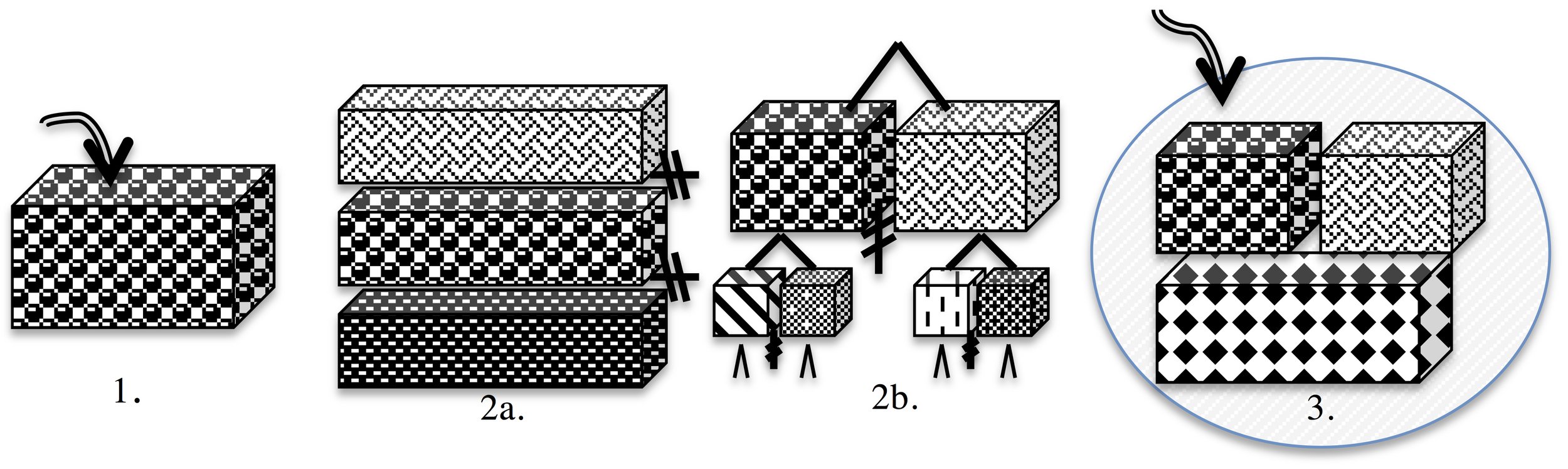

The release/consequent of this introduction (last four meas. of mark 5, meas. 48) is, on the piano, only made of repeated notes in crescendo-decrescendo. In the orchestral version, Ravel operates a subtle ‘geographical crescendo-decrescendo’, both in the repeated note layer and in the accompaniment layer (see fig.2.8): the string pizz accompaniment progressively extends to the first violins before retracting (see Debussy's La Mer, beginning of the 1st Mvt., or first measures of the 2nd mvt). On the climax (meas. 50), it even extends geographically throughout the orchestra (in all directions) to the winds at the back of the orchestra, space improvement-doubling the strings at the front, before retracting.

Each layer follows this space-based cresc./decresc. logic. In the main voice, the solo muted trumpet, traditionally directional (even if muted here, which mitigates the directionality) has its acoustic space widened by its doubling with two non-directional horns at the climax. This widely opened space of the sound then narrows to more concentrated focus after the climax (meas.50), but this time backwards with a horn - as its bell is directed towards the back of the stage.

Fig.2.8: crescendo/decresc. and space and focus changes (mm.48-52)

The antecedent of the main motif A3 (rehears. mark 6) is played by a wonderful doubling of harp and alternating flutes in triple-tonguing (one of the most difficult in the literature for flute for orchestra), while accompanied by string pizz.

The release/consequent of this motif A3 (rehears. mark 7) is inspired by motif 1. It is a wonderful step-wise crescendo in five steps of a music composed in four layers: the melody (ob.-> [flute 3rd oct.+clar./Eng. Hrn.+clar.] on one octave -> [winds on three octaves]) (in navy blue), a second castanets-like rhythmical layer (closed strings, tambour de basque, then brasses) (in light blue), a third layer (in purple) in [low pizz.strings+hpe +winds] alternating 6/8 and 3/4, and, like most of the ‘wet’ release, a ‘Pedal/sauce’ with hrns. relayed with trbns. (in yellow).

Fig.2.9: Instrumentation of the release of the motif A3 (step-wise cresc., mark 7, mm.59-63)

Let us note again that this crescendo is only written cresc. in the piano version, while orchestrated in the orchestra version: it is a good example of the difference between a technical cresc. and a functional crescendo.

2. d) Functional analysis of the orchestration of the beginning of section B (mm.72-108)

This section is well known for its instrumentation. For this reason we will be brief, as others have dealt with it. As other already said (Soden, 2019), we hear in this section the narrative of the “Gracioso“ (being a solo bassoon) slowly singing, regularly interrupted by a few guitar chords bathed in an ethereal atmosphere crushed under the sun. The solo bassoon songs a graceful, very expressive, quiet and quite recitativo melody, while the sunny atmosphere is symbolized by non-melodic but rhythmic arpeggiated guitar-like repeated chords bathed in a quite ‘liquid/wet‘ and ethereal atmosphere, played by the tutti orchestra. For this aim, the instrumentation opposes two sounds qualities: i) a quite dry and focused (but not very directional) mf solo bassoon in its high register, and. string pizz. chords doubled by harps, a crotales, a xylophone, a cymbal and a military drum for the guitar-like repeated chord, immersed in an ethereal 'sauce' constituted with ingenious strings arco, mostly in natural harmonics.

[1] Thanks to Pablo Andoni-Gomez, Jan Esra Kuhl, Ehsan Mohagheghi-Fard & Kit Soden for their proofreading and correction suggestions, & Kit Soden for the documented discussion on coupling vs. doubling.

[2] Kit Soden has another definition for coupling: it is a physical action joining instrument and register. If Samuel Adler and Rimsky-Korsakov both seem to slightly differentiate coupling, seen also more as an action, an intention (Adler, 2002 Norton, p. 5, 70, 112, 114, 446, 583; Rimsky-Korsakov, 1913, reprint 1964 Dover, p. 48, 58, 73), in analogy to the couplers in an organ that couple simultaneously different registers (Adler, p. 239), vs. doubling, seen more as a fact on the score, they both also reduce the coupling to “two instruments playing the same passage at parallel intervals“ (Adler, p.125). See fig. 1.2 as an example of coupling not being a doubling.

[3] In written language, an emoticon -short for “emotion icon“- has no semantic value, but it contributes to the meaning by indicating emotional signs instead of voice intonations and facial signs. In music there are many similar effects, where the composer composes an effect that indirectly contributes to the musical expression: punctuation, interjections, breathing or "lifting of the baton" before an impact (e.g. Ravel, La valse, rehearsal mark 13 & 85; the quivering of the strings at the beginning or on r.m. 7, 54, the celli-glissandi r.m. 48 are also emoticons)