Professor Bad Trip: Lesson III — Fausto Romitelli

Professor Bad Trip: Lesson III — Fausto Romitelli

Amazing Moments in Timbre | Timbre and Orchestration Writings

by Jonas Regnier

Published: June 27, 2024

Professor Bad Trip: Lesson III (2000) is a piece for small ensemble composed by Fausto Romitelli, constituting the last part of his Professor Bad Trip triptych (1998–2000). As suggested by the title, Romitelli sought an aesthetic that evokes hallucination, plunging the listener into a state of illusion and bewilderment. Romitelli’s pursual of this aesthetic is explicitly related to Henri Michaux’s book Misérable Miracle (1956, reprinted 1990), in which the author deliberately puts himself in a mescaline-induced trance and records the effects on his perception on the world around him.

“Professor Bad Trip is a trilogy inspired by the writings of Henri Michaux dedicated to the exploration of hallucinogenic drugs, mescaline in particular. I found analogies between the disturbances of hallucinated perception in Michaux's writing and the processes developed in my musical writing.” (Romitelli, 2000).[1]

To understand Romitelli’s musical methods of conveying hallucination, I will briefly analyze the beginning of Professor Bad Trip: Lesson III from the dual perspectives of score and recording, focusing on the listener’s perception of timbre and associated musical experiences.[2] Here is a recording of the full composition, although this essay will only focus on the first minute of the piece.

Repetition, transformation, and surprise: how to confuse listener perception of musical materials

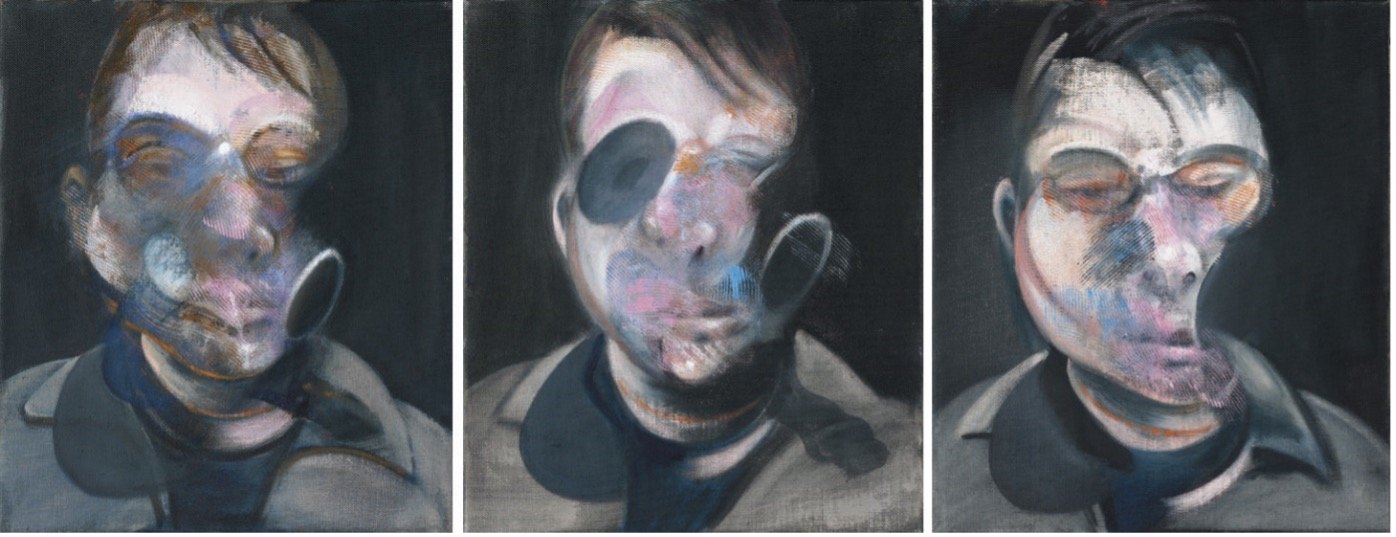

As in speech and visual arts, subtle repetition in music can create coherence and meaning. Three Studies for a Self-Portrait by Francis Bacon, another source of inspiration in Romitelli’s aesthetic (Moroz, 2020), demonstrates a material being conveyed through repetition (in combination with variation).

In Three Studies, the face is distorted and transformed from one portrait to the next. These changes of the viewer’s perspective of the painting are mirrored in Professor Bad Trip: Lesson III through the variations and transformations of an initial musical gesture, showing a means of using repetition without merely conveying the same message many times (also referred to as “developing variation” by Schoenberg). This type of repetition (or developing variation) is one of the most striking structural characteristics of this piece. Within the first five measures, each instrument plays the same cell a few times in a row. These obsessive repetitions happen throughout the piece on small, medium, and large scales.

For instance, the beginning of the piece (from measures 1 to 5, or from 0:00 to 0:35), which can be considered as a short introduction, presents the main musical material and gives us clues about subsequent pitches, gestures, and timbres. This principal material is a descending semitone glissando, exposed in its purest form in a slow tempo and having no discernable pulse (figure 2, mm. 1-5). Then, from measures 6 to 15 (0:36 to 0:53), Romitelli varies the same three-bar figure (figure 3, mm. 6-8) many times in a row, adding small timbral effects for every variation to renew the interest of the listener. On the first variation, a glissando on the cello, a natural harmonic glissando on the violin, and an electric guitar note are added to the original sounds (figure 3, mm. 6-8). In the second variation, a piano chord is added. Finally, for the remaining repetitions, this piano chord is slowly arpeggiated downward. This way of developing the musical materials through repetition and transformation is what brings coherence and surprise to the listeners’ perception of the form and the musical materials of this piece (in the same way that the face in Three Studies for Self-Portrait remains constant but some of its characteristics are varied).

Fusion and stream integration: confusion and clarity mixed to create hallucination

Despite its chaotic and detail-focused compositional construction, Professor Bad Trip: Lesson III follows a fluid and clear development, creating a continuous, coherent, and organic listening experience. We can explain this phenomenon using the principles of Gestalt theory (Koffka, 1935), which imply that a clear directional process compensates for the heterogeneous state of its components. According to this theory, perception and mental representation spontaneously process the phenomena of structured form and structured sets as a whole and not as a juxtaposition of individual elements. According to Irène Deliège, the intelligibility of a work depends on cognitive processes and memory. These processes are activated through perceptual operations such as storing, grouping or fusing.[3]

It is important to note the difference between concurrent grouping and sequential grouping (McAdams et al., 2022), as they both represent distinct grouping operations based on two separate perceptual effects in music. Concurrent grouping happens when we either group together or separate two or more simultaneous sounds. Two or more elements are said to be fused (or blended) with each other if they are perceived to belong to the same sound source. For instance, the first five bars of the piece represent a good example of a fused unit, as all the concurrent sounds seem to originate from the bell and piano attacks.

This concurrent blend can be explained in many ways. The first—and most obvious—perceptual operation relates to the concept of spectral overlap, which applies when all the instruments play close to the same note, in this case, a G (in blue, figure 2) and an F# (in green). This quasi-unison makes it difficult for the listeners to separate and isolate the frequency components of all the individual sources (Lembke & McAdams, 2015), resulting in the perception of one unified blended sound.

The second perceptual operation in effect in this introduction is the Gestalt law of common fate, which concerns items that vary simultaneously and similarly in the same direction. In this case, several instruments seem to follow the same “never-ending” descending glissando of a semitone (in orange, figure 2), which makes it even more difficult for listeners to separate and recognize each individual instrument. Romitelli’s choice of instrumentation also contributes to this perceptual fusion. The use of toy instruments in the piece (the kazoo, the guitar pitch pipe, and the harmonica) helps to blend all the different timbres with each other as they enrich and complement the muted orchestral instruments and add more confusion regarding the source of the sounds that are heard. The resulting concurrent blend could be perceived as an augmented timbre (McAdams et al., 2022), in which case the augmented dominant timbre could be perceived as the mixed bell/piano short attacks while the other subordinate timbres would be considered as an enhanced resonance of the bell/piano.[4]

It could also be perceived as an emergent timbre (McAdams et al., 2022), and the emergent timbre could be perceived as an electronic sound made of synthetic timbres distinct from any of the conventional ensemble instruments.[5] Furthermore, the combination of mutes (Harmon mute for the trombone, metallic mute for the strings), extended techniques (plunging in water to create a glissando effect for the tubular bell), and electric instruments (guitar and bass, with the use of an EBow, an electromagnetic device that can induce a progressive vibration on a string without any direct contact) is used to achieve these timbral augmentation/emergence phenomena and to confuse the listener’s ability to recognize the different sources of the sound. These phenomena, rarely explored in instrumental music in such an extensive way, represent the primary source of confusion experienced by the listener at the beginning of this piece and contribute to creating a sense of hallucination. Hallucination can indeed be described as either experiencing something that is not present or real (this relates to the timbral augmentation/emergence phenomena), or experiencing exaggerated and distorted sensory inputs (i.e., the perception of unusual colors, shapes or sounds).

Returning to questions of grouping perception, sequential grouping effects occur when we associate or separate two or more successive sonic events into streams (McAdams et al., 2022). This time, we are focusing on successive events (the “horizontal” aspect of music) instead of concurrent events (the “vertical” aspect of music). Auditory stream integration describes the succession of different sonic events being perceived as continuous and coherent through time. By contrast, auditory stream segregation describes sonic events being perceived as separated and distinct from one another. In the following excerpt (figure 3), each sonic event emerges from a separate sound source, but the articulation and organization of the music make us group these units together as a single phrase or stream, resulting in an auditory stream integration grouping effect. This stream continuity and coherence creates an effect of clarity for the listener, which contrasts with the sense of confusion experienced in the previous excerpt (figure 2). This contrast between confusion and clarity contributes to Romitelli’s hallucinatory aesthetic.

Although we can recognize that the different successive sounds all come from different sources or instruments—first the held clarinet high note (highlighted in red, figure 3), then the strings’ jetato (in yellow), and finally the flute aeolian/breathy sound (in purple)—we still group them together into a single stream as they seem to belong to the same phrase moving forward to one clear direction. This can be explained by the Gestalt law of continuity, which specifies that close points tend to be understood as a single, unified form when they are perceived as having the same direction or a predictable continuity. This three-measure articulation, repeated three times with small variations, is still perceived as one continuous entity despite the use of very different timbres and instrumental techniques. This sense of continuity is also emphasized by the constant use of the pitch G on the piano, electric guitar, clarinet and on the strings.

Conclusion

Romitelli’s evocation of hallucination in this piece is mainly obtained through two cognitive processes. The first is fusion—which induces a confused state of mind—and is obtained through detailed timbral choices that undermine the listener’s ability to recognize individual sound sources and create new, unreal sonic images. The second process is stream integration—which induces clarity and continuity—and is achieved through directionality of the musical discourse despite an eclectic timbral variety. Despite the often disordered and confusing textures, the continuity and coherence of the form give cognitive clues to the listener to ensure the intelligibility of the piece, particularly the use of frequent repetitions and highly directional articulations. Fusion, stream integration, and repetition are three cognitive processes that give meaning and strength to Professor Bad Trip: Lesson III, making it a good example of Romitelli’s ability to play with listener perception and timbral variation.

Works Cited

Deliège, I. (1987). Le Parallélisme, support d’une analyse auditive de la musique: vers un modèle des parcours cognitifs de l’information musicale. Analyse Musicale, 6(1), 73–79.

Romitelli, F. (2000). Professor Bad Trip: Lesson III (2000). https://brahms.ircam.fr/fr/works/work/14260/

Koffka, K. (1935). Principles of Gestalt Psychology. Harcourt, Brance and Co.

Lembke, S.-A., & McAdams, S. (2015). The role of spectral-envelope characteristics in perceptual blending of wind-instrument sounds. Acta Acustica United with Acustica, 101(5), 1039–1051. https://doi.org/10.3813/aaa.918898

McAdams, S., Goodchild, M., & Soden, K. (2022). A taxonomy of orchestral grouping effects derived from principles of auditory perception. Music Theory Online, 28(3). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.28.3.6

Michaux, H. (1990). Misérable miracle: La mescaline. Gallimard.

Moroz, N. (2020). Hacking the Hallucinatory: Investigating Fausto Romitelli’s Compositional Process through Sketch Studies of “Professor Bad Trip: Lesson I.” Archival Notes, 5, 59–84.

Score:

Romitelli, F. (2000). Professor Bad Trip: Lesson III [Musical Score]. Casa Ricordi.

Discography:

Ensemble Ictus. (2003). Fausto Romitelli: Professor Bad Trip [CD].