Across the Skies - Wenchen Qin

Across the Skies — Wenchen Qin

Amazing Moments in Timbre | Timbre and Orchestration Writings

by Linglan Zhu

Published: December 6, 2024

Introduction

The music of Chinese composer Wenchen Qin is often characterized by immediate connections to the topics of nature and religious spirituality. For Qin, the religious connotation in his music often serves specifically as the medium connecting humans and nature. One only needs to look at the titles of his compositions to see the prevalence of these two topics: Pilgerfahrt im Mai (Pilgrimage in May) (2004), The Nature’s Dialogue (2010), The Border of Mountains (2012), The Cloud River (2017), The Light of the Deities (2018), Poetry of the Land (2020), among others. Qin’s proclivity for these topics can be traced back to his childhood in Inner Mongolia where he was born. The vast landscape of Inner Mongolia, with its endless grassland interspersed with surging mountain ranges, bears a palpable trait of ruggedness and broadness of space, of which one can often identify musical counterparts in Qin’s music almost viscerally. Moreover, the folk music of the nomadic people living on the prairie (well-known examples include the throat singing practice khoomei), as well as the ritual music of Tibetan Buddhism (which is practiced regionally in parts of Inner Mongolia), had also deeply influenced Qin’s musical upbringing, and consequently, his later musical style.

In the context of these diverse musical and extra-musical influences, Qin addresses the topics of nature and religious spirituality not only through explicit aural references (e.g., instruments used in traditional ritual music, orchestral gestures mimicking natural sounds such as bird chirps and wind gusting, etc.). In fact, these two topics constitute the underlying sonic landscape of his music, often stark but with rugged power, where individual sounds are further shaped and polished in each specific context.

Timbral links between the pipa and the strings

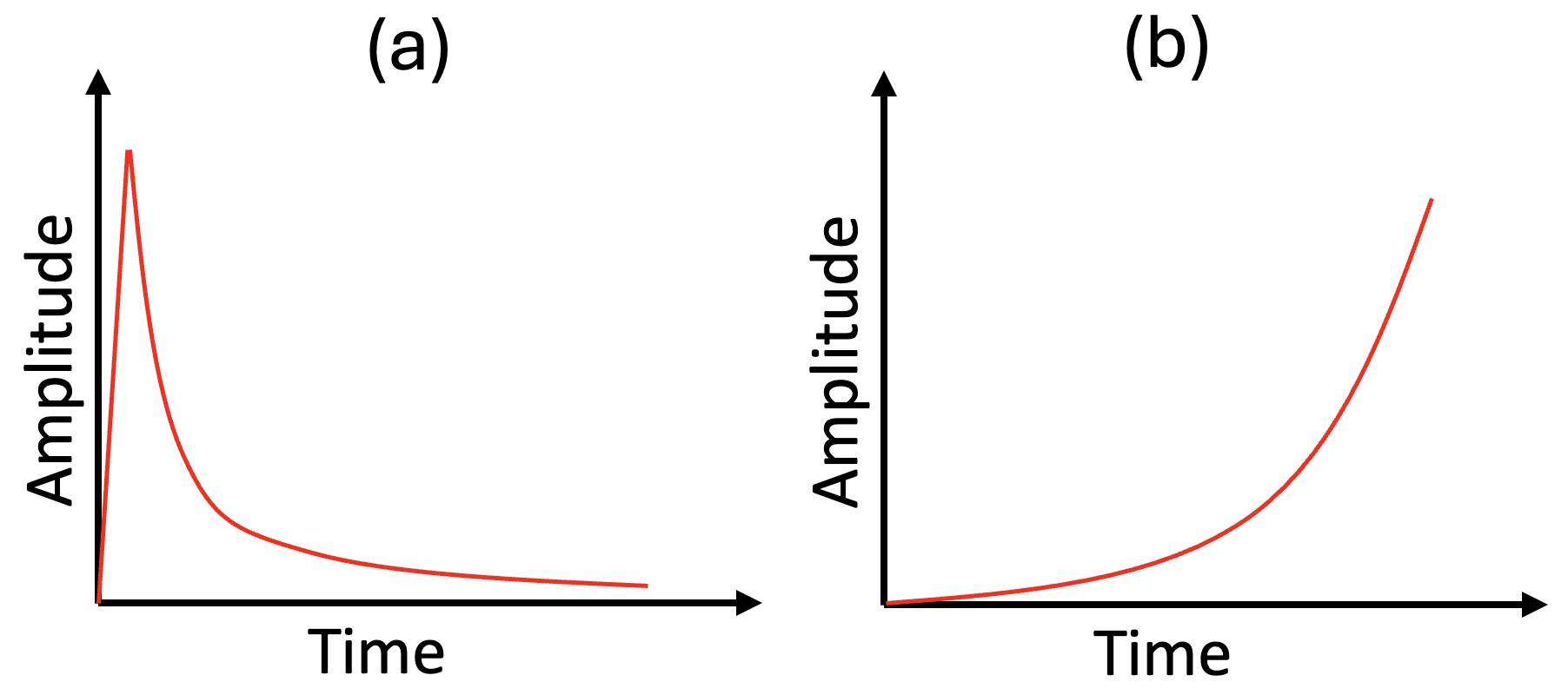

Across the Skies (2012), scored for pipa (see this ACTOR TOR module for additional information about pipa) and string orchestra, is an exemplary instance of Qin’s fine control and sensitivity of orchestral timbre while displaying his penchant for nature and traditional music. Set against the backdrop of the string orchestra, the solo pipa stands out distinctly throughout the piece with its own melodic contour and sonic logic that is primarily based on different modes of pentatonic and heptatonic scales. Qin also establishes a variety of sonic and gestural links between the pipa and strings throughout the piece, which originate from the common sonic potentials shared between them. One such link that Qin explores extensively is the use of natural and artificial harmonics. The opening passage of the piece showcases how Qin amalgamates the sounds of the pipa and strings harmonics while playing around with the timbral differences between the two. The opening solo pipa passage features a series of block chords with natural harmonics strummed on all four strings of the pipa. Specifically, the string orchestra functions as an “acoustic shadow” echoing the pipa by amplifying certain chords with string harmonics or normal notes played sul ponticello on the same pitches (occasionally with octave differences; see Example 1). Each of these string chords radiates out from the onset of the pipa chord it amplifies, starting dal niente followed by a swift crescendo to high dynamic levels. An interesting acoustical coupling is thus created locally on each of these highlighted chords: it can be seen from Figure 1 below that whereas the attack profile of the strummed pipa chord is made up of an abrupt attack followed by a quick release, the echoing string chord is a time-reversed version of the pipa chord. Aurally, one hears these two acoustic sources engaging in a constantly fluctuating timbral interplay where the relatively dry and granular pipa sounds are mutated and “stretched” into the more glassy and metallic string harmonics.

Figure 1: Graphic representations of the attack profiles of each of the pipa chords (a) and the string chords (b) in the opening passage.

Another timbral/gestural link between the pipa and the strings explored by Qin is based on the ability of both instruments to execute pitch bend. For the pipa, the use of pitch bend (especially as ornamentation) is commonly observed in the traditional repertoire and indispensable to its playing, as it delivers subtle inflection and liveliness to single notes. Starting from m. 50, a long meditative pipa solo is presented with sporadic accompaniment from the strings. An intimate call-and-response pattern is formed somewhat into this solo section between the pipa and the strings, with the latter imitating and amplifying the subtle pitch bend gestures of the pipa (see Example 2).[1]

Symbolic links between musical materials and extra-musical themes

In addition to these local highlights of timbral ingenuity, Across the Skies demonstrates how the themes of nature and religious spirituality in Qin’s music serve as contrasting elements and structural foundations for musical development. Three types of sonic materials can be identified that underlie Qin’s writing for the string orchestra in this piece (Jiang, 2021):

A ) Three perfect fifths stacked on top of each other (C–G–D–A). It is first presented at the very beginning of the piece on the violins and lasts until m. 27 (see Example 3). This idea reappears several times, including at the end of the piece. The stacked fifths played without vibrato on the strings are characterized by their sonic purity/simplicity, often serving as a calm backdrop underneath other musical activities. In a literal sense, this open sonority is the sonic token of the “skies” in this piece, the symbol of “nature.”

B) Diatonic texture containing all the white-key notes, either made up of stacked fifths (see Example 4) built on the diatonic scale or single lines from individual instruments (see Example 5). Instead of being presented as a block chord, the texture of this harmonic material is always animated, with each voice oscillating individually between neighboring diatonic notes. The interplay of diatonic harmony and the distinct motion of individual instrumental lines creates a “chorus effect,” reminiscent of the polyphonic choral style characteristic of medieval church music. This effect reflects the spiritual and religious undertones frequently present in Qin’s compositions (Jiang, 2021). As a variation of the three stacked fifths mentioned earlier, the diatonic texture here becomes more "materialized," meaning it is densified by the addition of multiple stacked fifths. In contrast to the pure, “sky-like” sonority described earlier, the diatonic sonority here exhibits a thicker and rougher tonal quality, resulting from the interaction and interference between pitches within the diatonic collection. On the other hand, the uniform pitch content gives the texture a “stagnant” quality. When combined with the continuous oscillatory motion of individual voices, the pitch homogeneity “freezes” the texture in time. In other words, the microscopic individual voice movements and pitch fluctuation are subsumed to one global coherent texture as if suspended in time. The religious connotation connected to church music, along with the “timelessness” quality described above, attributes a pale, solemn sonic character to this texture.

C) Chromatic cluster sonority: As shown in Example 6, where this sonority is first introduced in the piece, a clear trajectory can be traced both analytically and aurally, illustrating how the three types of harmonic materials are logically connected. The chromatic cluster can be seen as an extension of the diatonic sonority, with the sonic intensity building further from it.

On the surface level, these three sonic materials function as distinctive sonic markers that recur in various forms throughout the composition. Additionally, their large-scale alternation forms the structural foundation of the piece, generating fluctuating tension that drives the music forward and ultimately culminating in the resolution of the three materials into a unified whole in the final coda section.

Transcendence via unification: the coda section

The coda section (from m. 197 to the end) presents a unification of the three previously discussed sonic materials as a narrative element, with their sonic differences artistically "harmonized" through careful orchestration. The energy built up from the penultimate climatic section reaches its highest point and releases at m. 197 where the diatonic texture composed of interlaced perfect fifths returns, again conjuring up the image of medieval choral music (see Example 7). Compared to the diatonic texture presented earlier in the piece (e.g., Example 4), the texture here differs in two key ways that, in effect, “transcends” the same musical material and serves a narrative function. First of all, there is a much more prominent emphasis on the C natural in the low register, sustained by cellos and basses. The note C natural could be seen as the root of the stacked fifths chord (i.e., C–G–D–A, introduced as material A above), and the emphasis on this central note near the end of the piece has a strong gestural meaning of returning and unifying. Additionally, the strengthening of C natural also foreshadows the return of the stacked fifths chord shortly after in the coda section. Another notable difference compared to earlier instances of the diatonic texture is that, rather than remaining in oscillatory stasis, each individual voice gradually ascends in a canonic manner. Consequently, the overall sonority rises dramatically and thins out until the foundational fifths (C–G–D–A) emerge on the violas from the afterglow of this climax and are momentarily brought to the foreground. The three stacked fifths are then continued an octave higher on artificial harmonics, echoing the entrance of sporadic pipa harmonics, both of which persist until the end. Alongside the violas, the other string instruments adopt various articulations: elongated chromatic glissandi on the violins (either bowed or tremolo pizzicato with fingernails), harmonic glissando on the cellos, and the pedal note C (again, the root of the stacked fifths) droning on the basses (see Example 8). These various string textures blend organically into an acoustic canvas which foregrounds the pointillistic attacks of the pipa. The extremely hushed dynamics successfully veil any remaining traces of individuality of the string instruments, and the resulting effect is breathtakingly intimate and serene, at once sounding like the whining and rustling of wind on which the pipa gracefully glides through and eventually fades away.

References

Link to the score video of Across the Skies: https://youtu.be/P84RvGDjfh8?si=I4p-YZMUsmg2IgNH

Score excerpts:

Qin, W. (2012). Across the Skies [Musical Score]. Sikorski.

Recordings:

Across the Skies:

Weiwei Lan (pipa) / ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra / Gottfried Rabl (conductor), in Wenchen Qin: Orchestral Works, KAIROS, 2018.

Bibliography:

Jiang, S. (2021). On the phenomena of harmony and sonic characteristics — Study of Wenchen Qin’s chamber work Across the Skies. Journal of Shandong University of Arts, 2021(6), 34–41. [Original manuscript in Chinese]

Header photo:

CHAO Ge: LIAN CHUAN (oil on canvas)