Resources | Instruments | Chinese Orchestra | Wind Instruments

This page explores wind instruments of the Chinese orchestra. Here, you'll find an introduction to the dizi, xiao, suona, sheng, and guanzi, along with practical information on their techniques, ranges, and tonal qualities. Dive deeper into their history and construction, and understand their roles within the Chinese orchestra.

Introduction to the Instruments

Dizi

The dizi is a traverse flute usually made from bamboo. Likely originating from the Northwestern regions of China, the dizi has a long history with written records of the instrument dating as far back as the Han dynasty. It is used in various wind and percussion ensembles, as well as in operatic music. The traditional dizi has six finger holes, an embouchure hole, and a hole over which a membrane is pasted over. There are several different types of dizis that are regularly used in the Chinese orchestra. These include the bangdi, qudi, and xindi. These dizis are constructed in similar ways although they vary in sizes and timbre qualities, and can be used for different types of repertoire.

Sheng

The sheng is one of the oldest reed Chinese instruments, with a history of more than 3000 years. The earliest written records of such an instrument can be found in the oracle bone script writings from around 1500 B.C. Being able to play multiple notes at the same time, the sheng is often used in accompaniment passages, but it is also highly versatile and shines in melodic passages as well. The traditional sheng often has 17 reeds made of bamboo while developments in the recent years has created keyed instruments with up to 36 reeds (more common) or even more. There are several different sizes and the full range of these shengs in the orchestra would be able to cover the lowest to the highest registers.

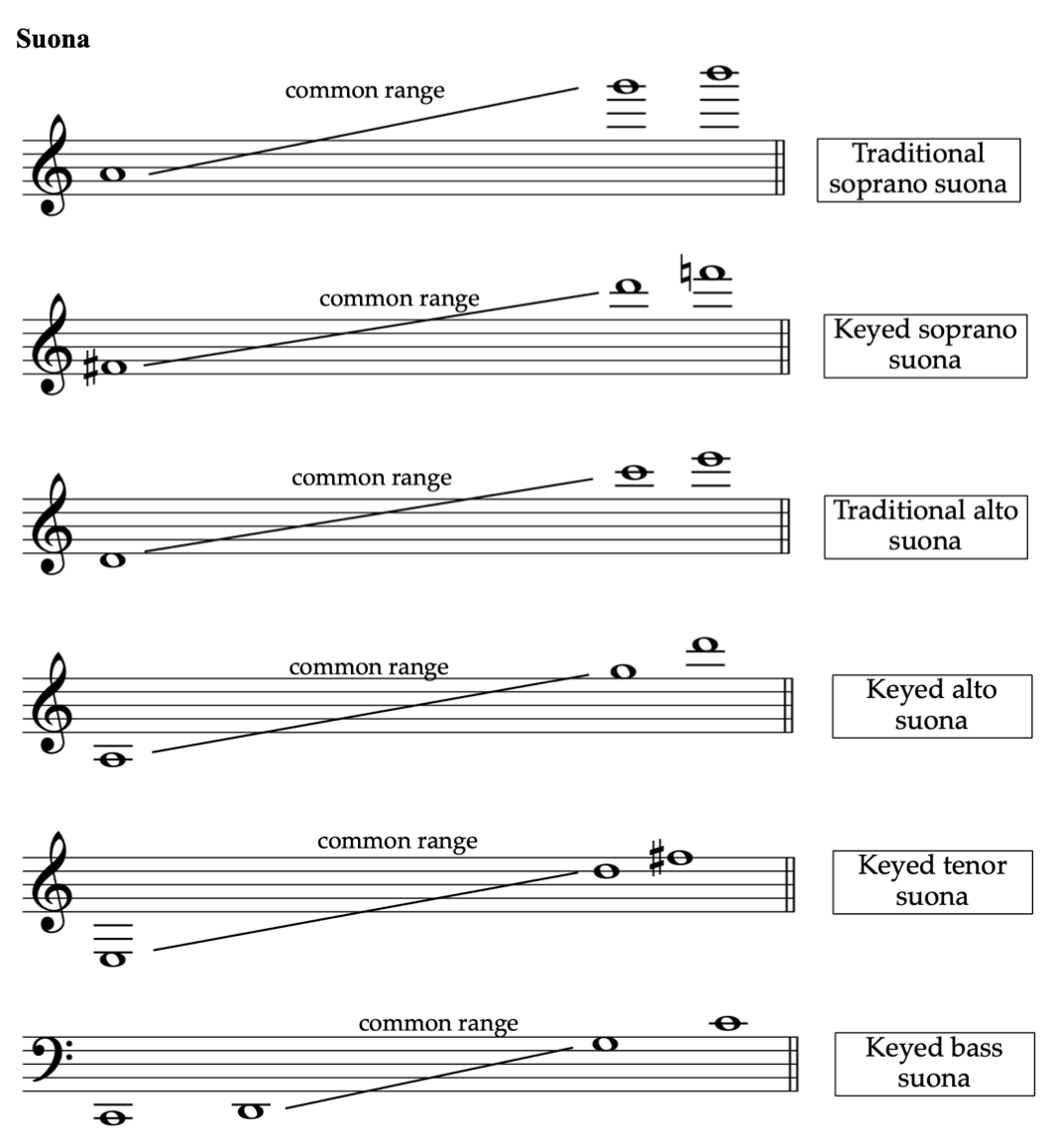

Suona

The suona likely came into China from the middle east as commerce and exchanges took place across the silk road. During the Yuan dynasty, it was mostly used as an instrument in the military because of its loud and commanding tone, but soon spread to the common people and became widely used in folk ceremonies such as weddings, funerals, and religious rituals. Now, the suona can be found in many different types of folk music around China. Recent developments have also created keyed suonas of different sizes and these are often found in the modern Chinese orchestra.

Guan

During the Sui Tang dynasty, another double reed instrument came into China from the lands of Ciuci (current Kashgar). It was called bili(篳篥). During the Tang dynasty, it was often used in court music, and the bili is often the lead instrument. Now, the guanzi is frequently found in folk wind and percussion ensembles, as well as Buddhist and Taoist religious music.

Xiao

The siao is a rim-blown vertical flute. It is thought to have been developed from a simpler vertical flutes in the southwestern part of China. There are different versions of the siao in the northern and southern parts of China. The siao is not a regular instrument in the Chinese orchestra but when it is present, it is usually the northern siao.

Practicalities

Techniques

Dizi

The dizis have similar playing techniques which will be grouped together in this section. Although all the techniques can be found in a modern composition, there are certain techniques predominantly found in the north and others that are seen more frequently in the south of China. There is a wide variety of blowing techniques to create different sonic effects. In addition to the different types of tonguing, the dizi player might also create a roll with their tongue. Vibratos can be obtained by either the breath or the fingers. Strong attacks can also be created coupling the use of breath and fingering techniques. The dizi player can also hold a note or play an extended phrase without a break with the use of circular breathing techniques.

Sheng

Depending on whether it is a traditional sheng with fingerholes or a keyed sheng more commonly found in the Chinese orchestra, fingering techniques may differ. However, there are also a wide range of blowing techniques that are shared. Sounds can be produced both from blowing or drawing the breath in. Various kinds of tonguing are used to create clear (or not) articulations, rolls, and so on. Glissandi can also be found, even though technically, the sheng is unable to create a smooth continuous change in pitch. The glissandi in the sheng is performed using a combination of finger and blowing techniques, creating a bright and clear ringing effect. Different types of vibratos can be created using various breathing techniques including throat/ abdominal/tongue control of the breath.

Suona

Different tonguing can be used to create a variety of articulation effects on the suona. Glissandi can be created using lip pressure, breath control, and finger techniques. A variety of vibratos can also be achieved with different types of breath control, as well as finger techniques. The sound of the suona can also be muted, often with hands placed over the bell, or changing the bell direction, but a variety of other mutes are also possible. The suona player can also use the technique of circular breathing to play an extended phrase or hold an extreme long note.

Ranges

Qualities

Dizi

Bangdi

Popular in the northern regions of China, the bangdi is a key instrument used for accompanying the bangzi opera. It is also found in many wind and percussion ensembles endemic of this region. The bangdi has a smaller body than the other dizis, and produces a bright, resonant, and clear sound.

Qudi

Mainly popular in the southern regions of China, the qudi was used in the accompaniment of kunqu opera, as well as several other regional operas. The sound of a qudi is thick and mellow, and is often used to play beautiful lyrical melodies.

Xindi

The xindi is the only dizi that does not have a membrane hole, and thus does not produce that characteristic buzz of the vibrating membrane like the other dizis. It is much easier to produce chromatic notes and therefore easier than the other dizis at modulating to other keys. The sound of a xindi is rich and mellow.

Sheng

The sound of the sheng can be shrill and bright in the high registers, silky and mellow in the middle, and strong and thick in the low registers. It is the only wind instrument in the orchestra that is capable of producing two or more notes at the same time and is therefore very useful as an accompanying instrument. However, it is also very versatile and can play soloistic passages as well.

Repertoire Examples

Section under construction…

In-depth

Construction and acoustics

Dizi

The dizis are diatonic instruments and even though it is not very difficult to produce chromatic notes on well-constructed instruments. Dizis are labelled by their tunings, and it is important to select the appropriate ones depending on the key and the timbre desired. The membrane over the bangdi and qudi create a characteristic “buzzing” sound.

Sheng

The sheng is made up of many pipes, each with reeds inside. When the tubes are covered, either with the fingers or the keys, air is directed through the reeds to produce a sound. In this way, it is possible to cover several holes and produce more than one note at the same time. Because of this, the sheng is also often used in accompaniment passages.

Suona

The suona is a double reed instrument with a slightly conical body that opens in a bell at the end. The reed is attached to a bocal with a circular disc. This circular disc developed because suona performers in the past had to play for long hours at weddings or rituals for funerals, and the disc helped as a support to reduce fatigue for the mouth and lips. Over time, this disc became an integral part of the bocal of the instrument. There are both keyed and non-keyed versions of this instrument, the non-keyed ones used frequently for traditional solo works. The keyed instruments provide greater accuracy and ease for chromatic notes but the non-keyed ones allow for a range of subtle nuances with fingering techniques.

Orchestration

Orchestration techniques and examples

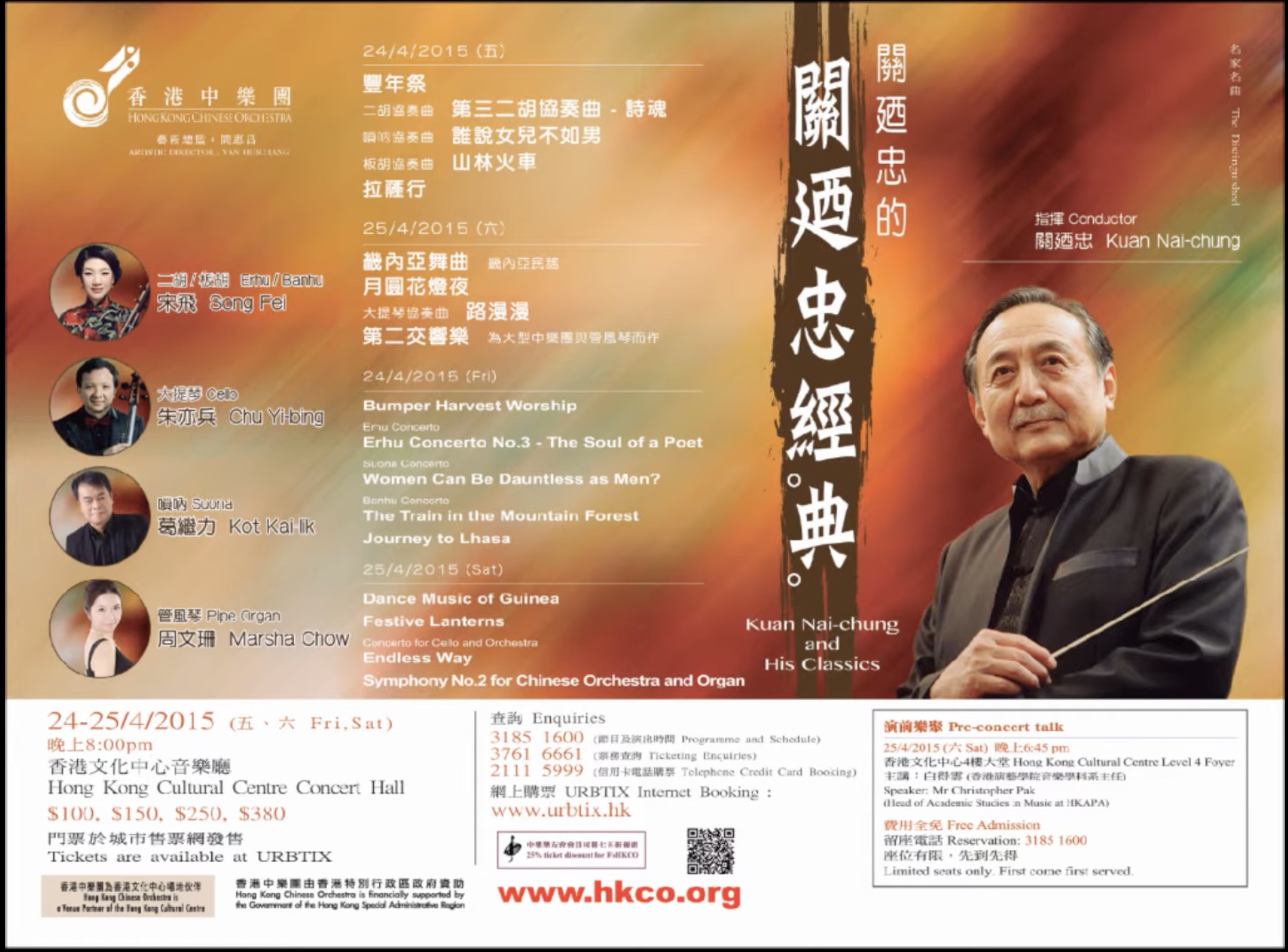

Excerpt from "Feng Nian Ji" by Guan Naizhong

This excerpt demonstrates a way of orchestraing for the dizi that brings out the traditional folk aspect of the music. The main melody is carried by the bangdi, and as a solo instrument, it is free to ornament the melody in its idiomatic way. The soprano sheng supports this with a counter melody, but as it are not parallelling the dizi's melody, there is no conflict even with elaborate Meanwhile, the accompaniment is supported by the rest of the orchestra except for the winds. This is possible because of the clear and bright timbre of the dizi that allows it to stand out even against the entire orchestra.

Excerpt from "Legend of Badang" by Koh Cheng Jin

When a strong, emphatic, or highly tensed effect is desired, it can be achieved by giving long held notes to the winds, achieving a full sound as seen in the excerpt below.

Excerpt from "Steering Your Own Destiny" by Liu Chang

Shorter repeated notes providing a chordal texture can also be used, and in this case, provides a different effect from the long held chords in the previous example. There is a greater feeling of forward motion, but at the same time great stability, especially when incorporated into a section that does not change quickly or much harmonically.

Excerpt from "Steering Your Own Destiny" by Liu Chang

When used together in unison with other instruments to carry the melodic line, winds can also help emphasize the melodic line. In addition, as compared to orchestrating for Western instruments where having almost all the instruments playing in unison or octaves might create quite and open and sparse texture, orchestrating in this way for Chinese instruments poses less of such an issue.

Heading photo by Amos Chua Ting Peng, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Houguan photo Badagnani at English Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons