Ulezo: Mapping Acoustic Attributes to Timbre Descriptors in Zambian Luvale Drum Tuning

Ulezo: Mapping Acoustic Attributes to Timbre Descriptors in Zambian Luvale Drum Tuning

Interactive Project Report

Published: June 26, 2024

Authors

Jason Winikoff (University of British Columbia) and Lena Heng (University of Prince Edward Island)

Introduction

How do Luvale musicians tune their drums with heat and tuning paste? How does this tuning process change a drum’s timbre? How do practitioners describe these timbres? And what acoustic properties are encoded in these semantic, descriptive terms? In this collaborative and interdisciplinary module, we address these questions through the case study of a two-step tuning process among Luvale drummers in Zambia.

In Luvale musical culture, drum tuning paste is called ulezo. The few extant studies of Luvale drumming have all made passing reference to ulezo’s importance (Malamusi & Yotamu, 2001, p. 6; Tsukada, 1997a, p. 352; Wele, 1993; Winikoff, 2018, pp. 56–57). Most styles of hand drumming in present-day Zambia utilize similar pastes (Brown, 1984, pp. 126, 128; Mapoma, 1980a, p. 110, 1980b, p. 632; Mensah, 1971, p. 23). This practice also extends beyond national borders into other related communities within this region of Africa such as the Chokwe and Luchazi (Bastin, 1992, pp. 27–28; Kubik, 1994, pp. 369–370, 2001, p. 5). Even outside of this area – in other parts of the continent and throughout the diaspora – tuning paste is an integral part of instrument construction, maintenance, and performance. While scholars acknowledge its importance in passing (Amegago, 2014, p. 156; Ankermann, 1976, pp. 50, 52; Blades, 1970, p. 60; Chauvet, 1929, p. 49; Euba, 1990, p. 130; González & Oludare, 2022, pp. 8, 14; Norborg, 1987, p. 123; Warner Dietz & Olatunji, 1965, p. 35), these studies mainly do not provide in depth analysis of the paste’s application or effects. However, acoustical and ethnomusicological scholarship dedicated to tuning paste in non-African/diasporic traditions often address these components. This includes literature on drumming in Myanmar (Bader, 2016), Japan (Suzuki & Miyamoto, 2012), Western popular genres (Worland & Miyahira 2019), and various Indian traditions (Beronja 2008; Gopal 2004; Rama Murthy & Rao 2001; Raman and Kumar 1920; Raman 1922, 1934; Roda 2015; Sathej & Adhikari 2009). Most of these studies are primarily concerned with overtone harmonicity and decay. Furthermore, they do not consider emic (insider), semantic descriptions of the paste’s effects. In this study, we consider two semantic descriptors of drum timbre (kukanguka and kumbumbula) and a wide range of statistically measured acoustic descriptors.

Timbre scholars often use acoustic descriptors to more quantitatively characterize the qualities of a sound. These acoustic descriptors are derived from analyzing the spectral, temporal, and spectrotemporal components of a sound. Spectral components of a sound include the frequencies of the partials within a sound, their relationships, and their amplitudes. Temporal components characterize how aspects of the sound change over time. By cross-analyzing local terminology used by practitioners with statistical data of acoustic descriptors, our exploratory research provides a novel case study that contributes to ethnomusicology and the burgeoning discipline of timbre studies.

Background Information

The Luvale are a matrilineal Bantu ethno-linguistic group who trace their lineage to the Luunda kingdom.[1] Though our research was primarily conducted in Zambia, Luvale communities are also spread around eastern Angola and southern Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Luvale are closely related to the Chokwe, Luchazi, Mbunda, and a handful of other, smaller tribes. Together, these groups are part of a relatively homogenous regional culture spanning a large part of central Africa.

Among other things, this regional cluster shares common components in its collectively rich musical culture. Much of the music in this culture involves antiphonal singing atop a polyrhythmic percussion ensemble. This music is featured in initiation ceremonies, festivals, as accompaniment for spirit manifestation, in healing rituals, recreational settings, and in professional music scenarios. To hear examples of this music, consult the various videos and recordings featured throughout the Makishi Music website or the following albums:

· Chisemwa (Lenga Navo Cultural Group, 2015a)

· Kafwa Mukwenu (Ulengo Culture Dancing, 2016)

· Milimo Yamwaza (Lenga Navo Cultural Group, 2015b)

· Mukanda na Makisi/Angola: Beschneidungsschule und Masken (Kubik, 1981)

· Music from Barotseland: Recordings in Zambia’s Western Province – Lozi, Mbunda, Nkoya, Luvale (Various Artists, 2020)

· Myaso ya Chisemwa Chetu (Likumbi lya Mize Chibolya Cultural Group, 2015)

· Zambezi (Lenga Navo Cultural Group, 2015c)

· Zambia: The Songs of Mukanda: Music of the Secret Society of the Luvale People of Central Africa (Tsukada, 1997b)

The Drums

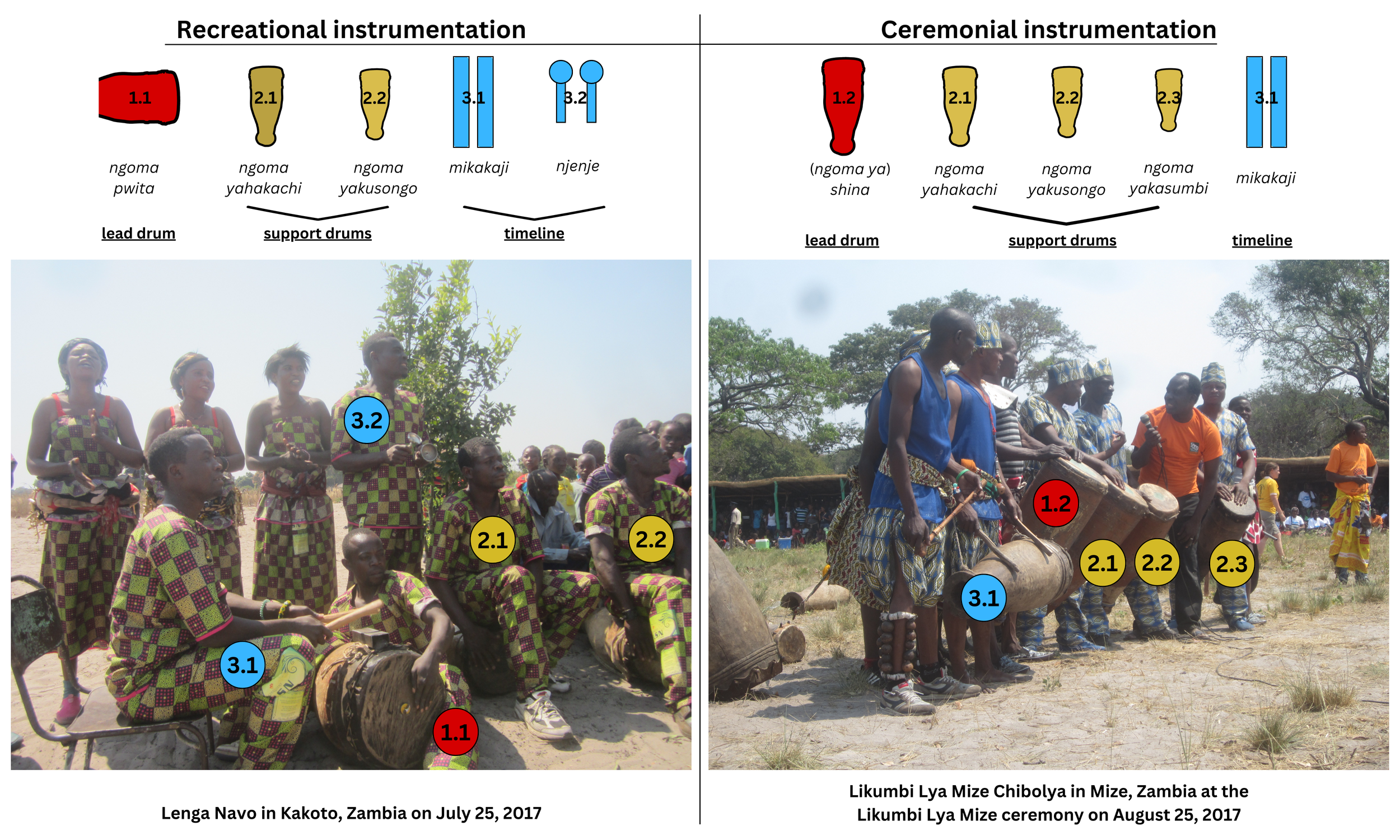

The Luvale percussion ensemble almost always contains a phrasing referent/timeline instrument, a lead drum, and at least two supporting drums. However, the exact instrumentation is determined by the music’s setting and purpose. Image 1 illustrates the two primary ensemble instrumentations. Four of these drums (shina, ngoma yahakachi, ngoma yakusongo, and ngoma yakasumbi) are all essentially different sized versions of the same single-headed, hand-struck, long, conical drum known throughout this region as ngoma.[2]

Unlike many drums from Eastern or Western Africa that utilize ropes, the ngoma affixes its cowskin head to the wood body through pegs. These pegs, however, are short – much shorter than (for example) the Ga kpanlogo of West Africa (see Image 2). As a result, drummers cannot rely on hitting the pegs to tighten drumheads. Thus, prior to performance (or at a set break during a long performance), each ngoma undergoes a two-step tuning process.

The Tuning Process

First, the pitch is raised through a method called kuzumisa (to heat). This also creates a sharper, drier tone with a more defined attack. With cooperation from the weather and enough foresight, this can be accomplished by leaving the drums out in the sun for a few hours. A quicker option is to place or hold the drum next to a fire for about five minutes (Image 3).[3] As fires are ubiquitous fixtures in Luvale villages, this latter method is preferred by many drummers.

Once the drum has been sufficiently warmed, the pitch is then lowered through the application of ulezo tuning paste. This also yields a deeper, rounder tone with a longer sustain. Ulezo seems to be defined more by its use than its components since there is a variety of ulezo recipes. Traditionally, it was made from jimono (castor seeds). Today it is usually created by pounding together a combination of fatty materials such as groundnuts, laundry bar soap, and motor oil. Image 4 shows a batch of ulezo created from this recipe. There are often regional reasons for specific tuning paste recipes. For example, the district of Kabompo has a high concentration of bees. As a result, drummers from this area often use honey in their ulezo. Other groups – often in/near urban areas – take advantage of manufactured material and simply use all-purpose putty. Regardless of the ingredients, each type of ulezo has the same effect on drums and is used interchangeably.

To apply ulezo, drummers press a chunk of the paste into the center of the drumhead in a roughly circular shape. They then expand its diameter and ensure a smooth, level layer is firmly attached. There is no predetermined amount of ulezo that must be applied; drummers use their judgement. However, one usually applies more paste to lower drums and less to higher ones – oftentimes not even using any for the highest drum (Image 5). During performance, some ulezo naturally flies off the drumhead so musicians often keep a batch nearby to facilitate reapplication.

Semantic Descriptors

When Luvale musicians talk about how the sound of the drums change during the tuning process, they often employ two terms: kukanguka and kumbumbula. Kukanguka means “to dry out” and comes from the word kukanga meaning “to cook in a dry pot over a fire” (Horton, 1990, p. 105). Both kukanguka and kukanga are frequently employed as descriptors for vocal timbre, labelling a voice as dried out, loud, and/or falsetto. In his analysis of timbre semantics in early orchestration treatises, Wallmark (2019) found that these types of semantic descriptors based on reference to aspects of matter are common ways of discussing timbre. In other words, musicians in many cultures across time have been labeling timbres with words that normally describe features of physical matter. Kumbumbula is a verb that either means “to produce the repeated mbú sound” or “to become slack” (Horton, 1990, p. 217). In this way, it describes timbre either through a sort of onomatopoetic action or again through reference to the material. Kufuna Joseph, one of the main translators with whom I work, translated kumbumbula as low or rumbly.

In addition to describing timbres through a sort of metaphoric reference to matter, kukanguka and kumbumbula can also be used to describe the physical properties of drumheads. In this way, a head can be described, respectively, as tight/dry or slack. Importantly, these do not conflict with their ability to alternatively (or additionally) describe sound; depending on its context, each word has the potential to label a physical state and/or a timbral percept. A ngoma drum can both have a tight head and produce a tight sound. Drumset musicians in the West often similarly use the same words to describe the physical properties of the head as well as its resulting timbre. This nuance of these terms’ employment reveals cross-cultural similarities regarding the ways in which drummers describe the confluence of tuning, timbre, and physical properties.

In an interview, Kapalu Lizambo, one of the most well-respected performers in Luvale and adjacent communities, employed conjugated versions of these terms when describing the tuning process. As the National Coordinator of Culture in the Likumbi Lya Mize Cultural Association (the organization appointed by the Luvale Ndungu chieftainship to protect, preserve, and promote Luvale culture) and a teacher to many drummers in this region, Lizambo’s words are representative of the sentiments many practitioners hold in this culture.

Original Luvale (OL): “Nge ngoma inambumbula vechi kumbatanga ulezo hikuhakako chipwe inambumbula, kumbata kukangula ku kakaya. Omu namukangula ize na ize ha-sound, ha lizu lize lyambwende. Chipwe nge inakanguka chikuma kumbata uno ulezo kuhakaho izenga haseteko yamwaza.” (personal communication, 29 June 2022)

English Translation (ET): If a drum [should] be kumbumbula, we get ulezo and apply it or if it is [too] kumbumbula, take it and warm it by the fire. When you warm it there is that sound, that good voice. Or if it is too kukanguka, now get ulezo, upon application it comes to a good size.

This is a clear statement of the timbres these tuning maneuvers either move towards or away from and when ulezo and heat should be employed. This establishes the semantic timbre descriptors kumbumbula and kukanguka as the poles of a spectrum, akin to timbral pairings in the West like bright/dark or smooth/rough (Figure 1). On this spectrum, heat makes a drum’s timbre more kukanguka (dried, loud, tight) and tuning paste makes a drum’s timbre more kumbumbula (slack, rumbly, low, capable of sounding mbú). Drums can exist anywhere along this spectrum. Completely untuned drums usually occupy the left-most pole – this undesirable, excessive amount of a kumbumbula timbre is usually only attainable with a head that has not received any treatment from ulezo, sun, or fire. Drums that have spent far too much time in the sun or by a fire are at the other pole to the right. The two-step process involves moving from one extreme to the other before eventually settling somewhere in between. A notable exception is the ngoma yakasumbi; the desired timbre and pitch for this drum are often reached after heating. This means that ulezo is often not applied to this drum.

Lote Sapato, a powerful drummer and dancer who has been featured in several Luvale dance troupes, tied heat to the kukanguka timbre in a similar manner.

OL: “Nge ize ngoma yambumbulanga, natuyihaka ku kakaya kuze. Yakukoka ize heat ize – chechilambu chize chakukolako chindende. Kuvetaho ngana: ndi ndi ndi ndi. Kunahu, inakanguka.” (personal communication, 11 July 2022)

ET: If that drum is [too] kumbumbula, we will put it to the fire there. It pulls that heat there – that skin is hardening a bit. Strike it and it sounds like ndi ndi ndi ndi. That’s it, it’s kukanguka.

Due to the ubiquity of these words in musician parlance, many collaborators found it odd to explain these terms in a formal interview setting. Indeed, the tuning process and discourse surrounding it are considered relatively obvious within Luvale drummer circles. This normalized knowledge and related discourse, however, does not involve explicit reference to the acoustic properties of their timbral percepts and maneuvers.

Stephen McAdams notes that timbre is a “perceptual property and not a physical one” although it “depends very strongly on the acoustic properties of sound events” (2019, p. 23). Cornelia Fales accounts for this dual nature with her concept of domains. In her influential study of the Barundi inanga chuchotée tradition, Fales distinguishes between the perceptual and acoustic domains of timbre (2002). The above interview excerpts from Luvale drummers, with their semantic descriptors, provide information on the perception of Luvale drum timbres. They indicate how drummers perceive the sounds but do not offer information about the physical acoustic properties that characterize their perception. For example, we know that a ngoma that has undergone significant heating has a timbre perceived as tight and dry. Is there a set of acoustic descriptors that accounts for sounds that are perceived as such? Drummers share this concept of what constitutes a good timbre; but does this reflect as a clear set of physical acoustic characteristics?

The following section outlines the process of our acoustic analyses to confirm our hypothesis that there are perceptually salient differences in the timbre of Luvale drums after each part of the tuning process. Furthermore, we hypothesize that there is a set of desired timbre characteristics that are consistently agreed upon by practitioners. In essence, this method allows us to translate the perceptual domain of emic, semantic timbre descriptors into the acoustic domain.

Measuring Timbre

First, we had to extract and analyze acoustic features from the drum sounds. The revised Timbre Toolbox (Kazazis et al., 2021) is a set of tools that computes various acoustic descriptors to characterize a sound. Some examples of these acoustic descriptors include spectral centroid, temporal centroid, attack time, to name a few. As our study is exploratory, we explored all the relevant acoustic descriptors that were computed in the Timbre Toolbox (harmonic descriptors for instance, were not included since the set of sounds are not harmonic in nature). This gave us 30 acoustic descriptors[4] which were used for the subsequent analyses, including the medians (central tendencies) and interquartile ranges (variability over time) of spectral, temporal, and spectrotemporal features.

The audio data for this study was collected on five-non-consecutive days in various locations. Jason Winikoff recorded several Zambian drummers performing multiple open, slap, and bass strokes on each of the drums (shina, ngoma yahakachi, ngoma yakusongo, ngoma yakasumbi) at three different stages: before any tuning, after kuzumisa (heating), and after ulezo application. He repeated this process for four different drum and dance troupes with whom he has worked for years (Chota, Lenga Navo, Likumbi Lya Mize Chibolya, and Likumbi Lya Mize Western Province Mongu). He also repeated this process twice with Lenga Navo. This resulted in a data set of 412 individual sounds.

Of those, we opted to only use the open strokes in this set of analyses because (1) they are the most important to Luvale drumming (Winikoff, 2021), (2) they are performed more consistently than the other strokes, (3) slap strokes often function as manipulations of adjacent open strokes, and (4) open strokes are significantly affected by the tuning process. This focus reduced our data set to 216 individual open stroke sounds. Representative examples can be heard in the audio examples below.

Shina

(audio examples performed by Chota)

Ngoma Yahakachi

(audio examples performed by Chota)

Ngoma Yakusongo

(audio examples performed by Likumbi Lya Mize Western Province Mongu)

Ngoma Yakasumbi

(audio examples performed by Likumbi Lya Mize Western Province Mongu)

The 216 audio examples were categorized by the three tuning stages, four types of drums, and four drum troupes. To determine the acoustic descriptors that best characterize the sounds of the drum strokes in each of the different tuning stages, we first used random forest, a machine-learning algorithm that uses decision trees trained on different parts of the data, to determine the descriptors that are important in classifying the sounds to the different tuning stages. From the analysis, five descriptors are found to likely play an important role in differentiating the sounds of the different tuning stages: spectral centroid, spectral decrease, spectral roll-off, temporal centroid, and zero-crossing rate.

Spectral centroid is a measure of the spectral center of gravity, an indication of auditory brightness (Figure 2). Spectral decrease (Figure 3) represents the amount of decrease of the spectrum, while emphasizing the slopes of the lower frequencies, and features in instrument recognition. Spectral roll-off (Figure 4) is the frequency below which 95% of the signal energy is contained. Temporal centroid (Figure 5) shows the center of gravity of the energy envelope and differentiates between sustained and detached sounds. Zero-crossing rate (Figure 6) shows the number of times the signal crosses the zero axis in a given time window and tends to be small for periodic sounds and large for noisy ones. It is important to note that each of these descriptors are not characterizing independent portions of a sound. Rather, they are describing different aspects of the same sound. It is therefore important to consider how they come together in perception. A sound with higher spectral decrease could indicate noisiness, but if combined with high harmonicity, could imply a rich and complex harmonic tone. It is a combination of all the various acoustic descriptors that can give a more complete understanding of a sound (c.f. Heng & McAdams, 2024).

The following boxplots show each of these five acoustic descriptors for the three tuning stages (Figures 7 – 11). The box represents the interquartile range (IQR) of the values in the particular tuning stage and the horizontal line within each box shows its median. Each point represents the value of a sound. We can observe that the values for “BeforeHeat” and “AfterHeat” flank the two extremes and the values for “AfterUlezo” are somewhere in between. This is because drums essentially overshoot their timbral and pitch goals in the heating stage. The ulezo stage then settles the pitch and timbre at a point in between where they began and where heat brought them. In other words, ulezo is used for (among other things) fine tuning and the findings from our acoustic analyses reflects this.

Conclusion

In general, these acoustic descriptors indicate that a lower spectral decrease and temporal centroid, and a higher spectral centroid, zero crossing rate, and spectral roll off characterizes a sound that is perceived as dried out, tight, and loud. This quality, emically described as kukanguka, can be achieved through the process of kuzumisa. A higher spectral decrease and temporal centroid, and a lower spectral centroid, zero crossing rate, and spectral roll off characterizes a sound perceived as slack, rumbly, and low. This quality is emically described as kumbumbula and can be achieved through the application of ulezo tuning paste. Figure 12 illustrates this summary.

As we have demonstrated throughout this module in both qualitative and quantitative manners, tuning has a significant effect on ngoma timbre. In the future, we hope to recreate this research with a much larger data set, ideally one created in a more controlled environment than what the field permitted for this study. This exploratory research offers a glimpse into the timbral effects of drum tuning and the ways in which drum timbre is conceptualized amongst Luvale musicians. Through a combination of ethnographic methods and statistical analysis, we can uncover relationships between the acoustic and perceptual domains of timbre.

Bibliography

Amegago, M. (2014). African Drumming: The History and Continuity of African Drumming Traditions. Africa World Press.

Ankermann, B. (1976). Die Afrikanischen Musikinstrumente. Zentralantiguariat der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik.

Bader, R. (2016). Finite-Difference Model of Mode Shape Changes of the Myanmar Pat Wain Drum Circle Using Tuning Paste. Proceedings of Meetings on Acoustics, 29, 1–14.

Bastin, M.-L. (1992). Musical Instruments, Songs and Dances of the Chokwe (Dundo region, Lunda district, Angola). Journal of the International Library of African Music, 7(2), 23–44.

Blades, J. (1970). Percussion Instruments and their History. Faber and Faber Limited.

Brown, E. D. (1984). Drums of Life: Royal Music and Social Life in Western Zambia (Nkoya, Lozi) [Ph.D., University of Washington]. In ProQuest Dissertations and Theses (303306474). ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. https://ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/drums-life-royal-music-social-western-zambia/docview/303306474/se-2?accountid=14656

Chauvet, S. (1929). Musique Nègre. Société d’éditions Géographiques, Maritimes et Coloniales.

Elliott, T., Hamilton, L., & Theunissen, F. E. (2013). Acoustic Structure of the Five Perceptual Dimensions of Timbre in Orchestral Instrument Tones. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 133(1), 389–404.

Euba, A. (1990). Yoruba Drumming: The Dùndún Tradition. E. Breitininger, Bayreuth University.

Fales, C. (2002). The Paradox of Timbre. Ethnomusicology, 46(1), 56–95. JSTOR. https://doi.org/10.2307/852808

González, M., & Oludare, O. (2022). The Speech Surrogacy Systems of the Yoruba Dùndún and Bàtá Drums. On the Interface Between Organology and Phonology. Frontiers in Communication, 6, 1–19.

Heng, L., & McAdams, S. (2024). The function of timbre in the perception of affective intentions: Effect of enculturation in different musical traditions. Musicae Scientiae, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/10298649241237775

Horton, A. E. (1990). A Dictionary of Luvale (Revised Edition). s.n.

Kazazis, S., Depalle, P., & McAdams, S. (2021). The Timbre Toolbox Version R2021a, User’s Manual. https://github.com/MPCL-McGill/TimbreToolbox-R2021a

Kubik, G. (1981). Mukanda na Makisi/Angola: Beschneidungsschule und Masken. Musikethnologische Abteilung, Museum für Völkerkunde Berlin, Staatliche Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz.

Kubik, G. (1994). Theory of African Music (Vol. 1). University of Chicago Press.

Kubik, G. (2001). Angola. In Grove Music Online. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000000944.

Kyker, J. (2019). Ngoma. Sekuru’s Stories. https://sekuru.org/ngoma/

Lenga Navo Cultural Group. (2015a). Chisemwa. Zambia Music Copyright Protection Society.

Lenga Navo Cultural Group. (2015b). Milimo Yamwaza. Zambia Music Copyright Protection Society.

Lenga Navo Cultural Group. (2015c). Zambezi. Zambia Music Copyright Protection Society.

Liaw, A., & Wiener, M. (2022). Classification and Regression by randomForest. R News, 2(3), 18–22.

Likumbi lya Mize Chibolya Cultural Group. (2015). Myaso ya Chisemwa Chetu. Zambia Music Copyright Protection Society.

Malamusi, M. A., & Yotamu, M. (2001). Zambia, Republic of (Vol. 1). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.30806

Mapoma, M. I. (1980a). The Determinants of Style in the Music of Ingomba. University of California, Los Angeles.

Mapoma, M. I. (1980b). Zambia. In The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (6th ed., Vol. 20, pp. 630–635). Macmillan.

McAdams, S. (2019). The Perceptual Representation of Timbre. In K. Siedenburg, C. Saitis, S. McAdams, A. N. Popper, & R. R. Fay (Eds.), Timbre: Acoustics, Perception, and Cognition (pp. 23–57). Springer.

Mensah, A. A. (1971). Music and Dance in Zambia. Zambia Information Services.

Norborg, Å. (1987). A Handbook of Musical and Other Sound-Producing Instruments from Namibia and Botswana. Musikmuseets Skrifter.

Papstein, R. J. (1978). The Upper Zambezi: A History of the Luvale People, 1000-1900 [Ph.D.]. University of California, Los Angeles.

R Core Team. (2023). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/

Sangambo, M. (1982). The History of the Luvale People and Their Chieftainship (2nd ed.). Mize Palace.

Suzuki, H., & Miyamoto, Y. (2012). Resonance Frequency Changes of Japanese Drum (Nagado Daiko) Diaphragms Due to Temperature, Humidity, and Aging. Acoustical Science & Technology, 33(4), 277–278.

Tracey, H. (1948). Ngoma: An Introduction to Music for Southern Africans. Longmans, Green & Co.

Tsukada, K. (1997a). Drumming, Onomatopoeia and Sound Symbolism among the Luvale of Zambia. In Cultures Sonores d’Afrique (pp. 349–391). Institute for the Study of Languages & Cultures of Asia & Africa, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies.

Tsukada, K. (1997b). Zambia: The Songs of Mukanda: Music of the Secret Society of the Luvale People of Central Africa [Compact Disc]. Barre, VT: Multicultural Media.

Ulengo Culture Dancing. (2016). Kafwa Mukwenu. Zambia Music Copyright Protection Society.

van Thiel, P. (1977). Multi-Tribal Music of Ankole. Musee Royal de l’Afrique Centrale.

Various Artists. (2020). Music from Barotseland: Recordings in Zambia’s Western Province—Lozi, Mbunda, Nkoya, Luvale. SWP Records.

Wallmark, Z. (2019). A Corpus Analysis of Timbre Semantics in Orchestration Treatises. Psychology of Music, 47(4), 585–605. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735618768102

Warner Dietz, B., & Olatunji, M. B. (1965). Musical Instruments of Africa: Their Nature, Use, and Place in the Life of a Deeply Musical People. The John Day Company.

Wele, P. (1993). Likumbi lya Mize and Other Luvale Traditional Ceremonies. Zambia Educational Publishing House.

Winikoff, J. (2018). Zambian Luvale Ngoma: Timbre, Voice, and Rhythm. Tufts University.

Winikoff, J. (2021). Kuvunga: Timbre, Interlocking, and Composite Melodies in Zambian Luvale Ngoma. Future Directions of Music Cognition. Future Directions of Music Cognition, Virtual.